What is lean documentation and how can you achieve it? Our guest on today’s live podcast is an expert on quality management systems, audits, and most importantly for today’s conversation, documentation. Steve Gompertz is a partner at QRX Partners and has led initiatives in project management, engineering automation, configuration management, audit, and software development.

During today’s episode, we’ll talk about the most important parts of a QMS, what differentiates a good QMS from a bad one, and how to prove ROI on a QMS. Steve will also discuss what he would do if he were starting a medical device company today. Listen to the episode to learn more about lean documentation and how you can learn to write for your actual audience – the workers – while still pleasing the auditors.

Watch the Video:

Listen now:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some of the highlights of this episode include:

-

What it means to have lean documentation, and what the norm is in the MedTech community

-

How to write for employees while meeting auditor requirements

-

Building a template for a standard operating procedure

-

Collaboration between the production of a document and ownership of that document

-

Making repairs on documentation vs. starting over

-

Proving the ROI on a good or bad QMS

-

Taking care not to be overly prescriptive

-

The importance of root cause analysis over treating symptoms

-

Mapping instead of including every SOP and repeating yourself

-

What management responsibility looks like

-

Making documentation work better in terms of root causes

Links:

Memorable quotes from Steve Gompertz:

“I’m fond of telling people, ‘The auditors don’t work here. That’s not who these documents are for.’”

“Done correctly, efficiency and effectiveness are not enemies.”

“Everybody has a customer internally; everyone produces a product.”

“On the quality systems pyramid, the smallest piece is the quality manual. So why is it the biggest document.”

Transcript:

Etienne Nichols

00:00:11.720 - 00:02:30.390

Hey everyone, welcome back to the podcast. My name is Etienne Nichols. I'm the host of today's episode.

In today's episode, we did something a little bit different. We've been doing this a little bit more, but we did a live podcast, so it was still done virtually, but we did it in front of an audience.

So, we tried to answer questions as we went through this. Today's topic was lean documentation. How to make your documentation actually work for your company instead of the other way around.

This was with Steve Gompertz from QRX Partners. Steve is an expert on quality management systems, audits, all things related to quality documentation.

He leads initiatives in project management, engineering, automation, configuration management, audit, software development for companies including St. Jude Medical, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Vital Images, control data. He's a mechanical engineer from Lehigh University and he also teaches at Saint Cloud University.

He is a fantastic resource to know, so if you love this episode, feel free to reach out to him on LinkedIn. I'm sure he'd love to hear from you.

We answered a lot of questions like do you have any way of proving the ROI on a good versus a bad quality management system? What's the most important part of a quality management system? And if you were starting a medical device company, what would you do first?

Would you do all of it? Would you do it in phases? How would you do it? What Phases would you go? A lot of ground we covered. I hope it's beneficial today.

So, I hope you enjoy today's episode on Lean Documentation with Steve Goperts. Hey, Steve, how are you doing?

Steve Gompertz

00:02:30.710 - 00:02:31.590

Good, how are you?

Etienne Nichols

00:02:31.830 - 00:02:45.970

Good.

Just to give everybody an idea of how this will work, we're planning to kind of do our podcast conversation and we're going to be talking about Lean Documentation. And today with me is Steve Gompert's. Am I pronouncing your. We've talked about.

Steve Gompertz

00:02:45.970 - 00:02:47.170

You got it, you're practicing.

Etienne Nichols

00:02:47.250 - 00:03:23.750

I got it. All right. That sounds great. He's an expert on quality management systems, audits, all things related to quality documentation.

He's led initiatives in project management, engineering automation, configuration management, audits, and software development for compute companies including St. Jude Medical, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Vice, Vital images and control Data.

He's a mechanical engineer from Lehigh University and has certifications in QMS, Biological, biomedical auditing, project management, and configuration management. At some point we're gonna have to talk about configuration management, I think. But as many times as I say that, thanks for being on the podcast.

How are you doing today?

Steve Gompertz

00:03:24.230 - 00:03:25.830

I'm doing great. How are you doing?

Etienne Nichols

00:03:26.070 - 00:03:44.800

Doing well. It's been a little while since we've done one of these, but I'm excited to have you back and I guess maybe we just go ahead and dive in.

You know, we've been talking a little bit about Lean Documentation in the past, but I'm curious, what, what does it mean to have Lean Documentation and. Or maybe a better question is what's the norm in the MedTech industry that you've seen?

Steve Gompertz

00:03:45.520 - 00:04:55.640

Yeah, so I mean, the basic concept is a less is more approach, but unfortunately that, that doesn't seem to be the standard. The traditional approach is more words, more words, more words.

Because we get an audit finding, we've got a cap, we have problems with our metrics, and we feel like we have to get ever more prescriptive in the documentation that we provide to our employees.

And my view is sort of heretical going, no, that actually heads you in the wrong direction and that you increase the likelihood of being non-conforming and non-compliant or just not being able to understand what is the point that you're trying to get across to the readers and I think the readers get left out a lot. The intended audience. To me, the big problem is too often quality system documentation is written for the auditors.

And I'm fond of telling people the auditors don't work here. That's not who these documents are for. Yes, check them. But they're for your employees. All right.

And for certain segments of your employees, you know, all good writers will tell you got to know your audience. Same thing with good presentation skills. The same thing goes for quality system documentation.

Etienne Nichols

00:04:56.200 - 00:05:11.560

Yeah, that makes sense.

I guess if I were to push back a little bit, though, there are people out there who said, well, yeah, they're not for the auditors, but the auditors are going to look at them and they'll hammer us if they're not a certain way. So how do you answer that question? Or what's your response when people say that?

Steve Gompertz

00:05:11.560 - 00:06:08.770

It's not that the information won't be there, it's how you structure it. Again, thinking in mind. And I often talk about; there's no rule that says you just need to have this textbook of a document.

You can start with what you think one audience needs, and then you can add detail in other places in the document, like appendices. Right. Where if somebody needs to dive in deeper, that information is there. But that's probably not what they're going to start with.

But that's typically how we write things. We write these procedures, and they're just like I said, paragraph through paragraph, paragraph.

And you're trying to slog through it and figure out, where am I and what did I. You know, and it's like, you know, that's not what the. The intended audience probably wants.

They probably want a flowchart with a little bit of information and a pointer to, where can I get the rest? If there's a table involved, where's the table? Don't embed it right at the point you think they need to see it.

They'll go get it if you tell them how to find it. So, okay. Just about thinking about that. Structure and flow.

Etienne Nichols

00:06:09.810 - 00:06:31.370

Yeah, that makes sense. And I can appreciate that. Maybe let's do this. Would you be willing to just kind of go through an exercise and.

And how would you build out a template for a standard operating procedure? I mean, because you mentioned, you know, putting something at the end and the appendices versus not what if.

Would you just be able to step through what you would advise someone if you were building one right now?

Steve Gompertz

00:06:31.850 - 00:08:19.410

Yeah, so I got this. The light bulb for me went on years ago. So not one of my. My best bosses, but he did tell me one thing that was useful. I was.

I was having a review, a new procedure that affected him, and he was looking through the SOP and he kind of just looked up and he goes, why is it I don't get to the part I need until eight pages in. Oh, okay. Oh, that hurt. You know, I had to think about that, and I was like, you know, you're right.

Because the traditional is, you know, you got purpose, you got scope, you got definitions, you got related documents, roles and responsibilities. Sometimes the change history is in there, and then finally you get to the procedure. Right?

And over time, those, those first things get in the way, and they get bigger and bigger. And then finally, you know, the procedure is now eight pages down. Right? I am always a big fan of purpose and scope first. Right?

That, that part we got, right? You have to, you know, when the reader opens a document, what is this document? Am I in the right document? Roles and responsibilities.

Do I play a role in this? Can I find myself in this?

And then procedure, jump into the procedure, all that other stuff, definitions, inputs, outputs, reference documents can all go in appendices in the back, as long as you reference it somewhere. And even if you don't reference it, people just get used to the idea the details are in the back.

If I can't figure out what a certain term is, I know there's a definition section in the back of this document. The whole change history thing is getting ridiculous because everybody uses eQMS which have the history.

So why does it have to be in the document when it was in the system? To help me find the doc, I usually give a little bit on that and go, okay, have the latest changes at the end somewhere.

What are the most recent changes? But not five years of history where we're now up to rev ac.

Etienne Nichols

00:08:21.170 - 00:08:21.450

And.

Steve Gompertz

00:08:21.450 - 00:09:12.659

The change history takes up five pages. So, yeah, and it's again thinking that how are they going to want to find it?

Typically, somebody gets into a procedure, they want to get a sense for the general flow. That's all pictures, right? Diagrams, flowcharts.

I've gone to a format where the flowchart is vertical along the left side and on the right is a little bit of verbiage for each block in the diagram. If more detail is needed, then there's a reference. If you need to see, for additional details, see section 7 of this document.

So, they know you're giving them the trail of breadcrumbs.

But what I find more often than not, when we're training people or when they're telling me, you know, how they use the document to go back for reference, they say, I never usually have to go past the flowchart because that was what I needed. I needed to see the activities. I needed a little Reminder of what it is. And then I was good to go.

Etienne Nichols

00:09:13.540 - 00:09:53.090

Okay. And I, I feel like we need to go even deeper than with flowcharts, because I. In my past, I remember looking at. What was it?

I think it was the design and development sop. I don't know, it's been so many years.

But anyway, we had a flowchart that was, I mean, you needed to print it on B size or maybe even, you know, bigger paper just to really get. And then you'd get your magnifying glass out and you just, you'd almost need to draw the line to make sure you get from point A to point B.

It was so complicated.

And I've heard people say, well, don't put flowcharts in your SOPs because it could be an audit trap when they don't match the, the wording and the verbiage in the paragraph. So how do you handle that? What's the what? I mean, there's got to be.

Steve Gompertz

00:09:53.850 - 00:12:06.260

Not everything needs to be in one document. You can create a hierarchy. You can create a bill of documents basically that are linked.

Just like in every good quality manual, there's always that pyramid that shows the hierarchy of documentation. Well, use that too often. We intermix and we feel like, oh, they'll only read it if we put it all in one place.

And now all of a sudden, it's a 30-page SOP. Well, nobody wants to read that.

And yeah, if you tried to put all of that information into something visual, yeah, you're going to get a rat's nest of a workflow diagram that nobody's going to be able to pay attention to. Nobody's going to be able to maintain. And then like I said, it's just a trap for audit findings. You have to kind of think about hierarchy. Right.

Start with, well, what's the high-level process? Oh, you know, there's that section of ISO 1345.0.1 that nobody ever reads that talks about applying the process approach. Right.

And that's what it's getting at is where's the process in all of this? Right. What are the bigger activities? That's a simple flowchart. Now, all right, there's a block of activity that occurs here. Right.

Phase two of design and development is conceptualization or something like that. Okay, how about there's an SOP for conceptualization.

I drill down, I go to that SOP underneath this process document, and now there's a little bit more of a flowchart that says, okay, these are the more specific tasks we're going to perform in order to get this done. How do I do that particular task? That's where work instructions come in when we need them.

Not every task needs a work instruction, but when we need to be really prescriptive about the steps, now that goes in a separate work instruction. And people get used to being able to traverse this and it just becomes. It sounds like it's just going to be a nightmare.

They really would prefer to just have it all in one document. No, because that one document is just too unwieldy. They would really rather drill down and once they understand the structure.

I've done this in a number of places. I've never had anybody complain. They always go, now I know where to find everything. And they actually do go find things. And that's the other thing.

Because otherwise, if the documentation's just too burdensome, they won't ever go back to it. And then that's when they start making mistakes.

Etienne Nichols

00:12:06.500 - 00:12:11.820

And I assume when you have those built out, it would be hyperlinked together or. What are your thoughts there? There any again?

Steve Gompertz

00:12:11.820 - 00:12:33.920

Right. Take advantage of today's modern. Yes, you can do that. Right. So, you know, you do have to maintain it.

Now, usually the pushback then is going to come from the doc control department going, we have to manage all of this. Yeah, yeah, sorry. That's your job these days, you know, welcome to this century. This is what that looks like.

It's about content management and relationship management. It's not about pushing an echo through the system.

Etienne Nichols

00:12:34.400 - 00:13:07.650

That's right. Yeah, that makes sense. One other thought, though, I. Or maybe a question I had about the flowcharts.

Do you have any, I don't know, guardrails to put in place so that it doesn't get to be so unwieldy? Because I can even see someone get. There are so many. There are people who are so detail oriented, they would break down every.

If you were in project manager, that the work breakdown structure past that, the tasks that I might put out for five tasks would be 50 tasks for them. And so, depending on who builds out that flowchart, what are the. The guardrails you'd put in place so that it doesn't become an audit trap.

Steve Gompertz

00:13:07.650 - 00:13:52.730

Again, the guardrail are the readers, the intended readers. Too often as authors, we get too enamored with ourselves and what a great document we put together.

We forgot to ask the people who are going to read it. Right. So, yeah, I'm highly detailed and like you said, my work breakdown structure has 50 items where five probably would have sufficed.

I'm not the one who's making that decision. Who is this document intended for? They're going to tell me whether I got it right. And that's where they go. So, you got to kind of swallow your ego.

If they come back and go, I know, I don't want 50 pieces of information. I want five. I don't care how much you feel like 50 is right. They're the ones who are going to use it.

You've got to, you know, say, all right, I'm doing this for you, not for me. That's a tough one. I know for some people that, that's.

Etienne Nichols

00:13:52.730 - 00:14:14.530

Another interesting question that maybe we could go into. And that is the owner of that document, the owner versus just quality assurance in general.

Because a lot of times, for some reason, quality has a big part in producing whatever document it may be. And I suppose that's because they're closest to the regulations. What are your thoughts about that production of the document and then the ownership.

Steve Gompertz

00:14:15.170 - 00:14:55.260

It's got to be collaborative, you know, it can't be. It's not just the readers or just the author. Right. They've got to work together because you're right. Often the owner is the expert on this stuff.

So, it's, it falls on them to influence. Right.

And make their point and then listen to, well, all right, if you did a good job of that, then the users will say, well, here's how I can make that happen and how I can't make that happen, you know, and then find that, find that win, win, you know, and, and that's going to produce much better documentation that both sides can live with. But too often, yeah, it's like, you know, these, these ten Commandments came down from the mountain. No discussion.

Etienne Nichols

00:14:56.300 - 00:15:33.080

That's right. And it's. You bring that up. It's interesting because, you know, there's two sides to every SOP.

There's the, the whoever's going to come in and audit us. We, we are. Part of the reason we're doing this is to meet a regulation, not. Not to meet an audit.

Like you said, this isn't written for an auditor, but it is to meet a regulation. But the other side of that is to meet the business need, whatever that business need may be.

And yeah, sometimes we look at the regulatory side as much higher than the business scene, when in reality, I don't. They're. They're probably not even 50. 50. The business need is a lot higher. And I want to. I have a question about this.

So, I'm going to get to my point here. Just a minute.

Steve Gompertz

00:15:33.080 - 00:15:33.320

Sure.

Etienne Nichols

00:15:33.320 - 00:16:08.970

I just thought I just taught something on QSR for wraps and all that knowledge that I taught them is about to be obsolesce by QMSR. But whatever.

And, but there's a phrase in 820.1 called scope that we never read as well, but it talks about if a manager engages in only some operations subject to the requirements in this part and not others, that manufacturer only needs to comply with the requirements applicable to the operations, which is engaged applicability, basically. So, what are some of the things that you see people trying to build documents around when in reality it should just be out of scope for that company?

You ever see anything like that?

Steve Gompertz

00:16:09.690 - 00:16:13.680

It's usually the opposite. It's usually people are trying to exclude things that they shouldn't.

Etienne Nichols

00:16:13.680 - 00:16:14.360

Oh, okay.

Steve Gompertz

00:16:14.520 - 00:16:55.080

Right.

So, we, we deal with a lot of contract manufacturers and the first thing they'll do in their quality manual is exclude themselves from design controls. And it's like. So let me, let me get this straight. Your clients come in, they give you an. Yeah, because the design comes from the client. Fine.

The client comes with it, and they give you the manufacturing process too? Well, no, we figured how to manufacture it. Okay, See, that's development, which is part of design control.

So, you, you might be able to exclude yourself from the design in design and development. Part of design controls, but not the development piece. Right.

So, I often see that, I see things like where software is a medical device and they want to exclude themselves from servicing because there's nothing physical.

Etienne Nichols

00:16:55.400 - 00:16:55.960

Okay.

Steve Gompertz

00:16:56.600 - 00:18:19.150

Servicing includes your customer support group. And when you have to issue patches and things like that, that would be considered servicing.

So, it actually is hard to exclude things because unless what you're doing is so targeted, usually the easy ones are, well, our device is not sterile. Great. There’re a couple easy ones to exclude. But excluding some of the larger sections.

You're gonna have a tough time convincing me at least that you don't actually have a role there and have things to control.

What's often funny when I go into these CMOs and they've excluded themselves from design control, and then I go and do an audit, they have a procedure for design control. I was like. And I was going to go, so why'd you write one if you were going to exclude. If you excluded yourself from it? Right. So, they know.

They just think it sounds good to tell the auditor we've excluded it. The auditor is going to find that there is a product development process in there or A product transfer. And that's a big part of design transfer.

Fine. Whatever you do, you always gonna. The CMOs by nature, by definition are design transfer. Right. Turning the specification into something real.

So, yeah, I think it's actually kind of hard to pick good exclusions. I've rarely found where somebody is covering something and I go; you don't need to. That doesn't happen very often.

Etienne Nichols

00:18:19.710 - 00:18:20.910

Yeah, that makes sense.

Steve Gompertz

00:18:20.990 - 00:18:29.080

The only place that would come in, and this is like a whole another podcast discussion, is about when you need to do process validation. That gets overdone a lot out of fear.

Etienne Nichols

00:18:29.960 - 00:18:33.600

Yeah. Well, we have to do that sometime because there's so much confusion about it.

Steve Gompertz

00:18:33.600 - 00:18:34.440

But there is.

Etienne Nichols

00:18:34.600 - 00:18:55.560

I know that some conversations on LinkedIn through that. And yeah, at some point we're going to have to hamper that down. Okay.

Another question that I might have is, what in your mind, it's going to be subjective a little bit. But what's the most important part of a QMS if you were to kind of look through, is there any one section that stands out as incredibly important?

Steve Gompertz

00:18:57.010 - 00:20:17.610

No. Because it's so dependent on what you're doing. Right. That the priorities will change.

But when you first started to say the question, the first thing that came to my mind was that in 1345, is section 0.1. Process thinking. The word system and quality system have significance. Right.

Having all of your procedures written so you can check them all off that checklist mentality does not create quality, does not create a quality culture. Right. You have this pile of procedures, and nobody knows how they go together except through anecdotal information. That's not the intent.

You should have thought through processes. How do these things flow? Right. From process to activities, down to tasks, down to records. That's kind of the hierarchy. And yeah, that's hard.

I know I have to see it all. And yes, that's what section 0.1 is saying to you. First figure it all out. How is it laid out? What's the architecture look like?

Then from there it gets a lot easier. Yeah, we've got. We've got clients. We're doing that for where we. They've had a quality system for years and now they're just tripping over it. Right.

It's not really providing value. And it comes down to they never architected it and we're burning it down and building them a new one, you know, because they have.

They don't have any idea what the structure is supposed to look. Look like.

Etienne Nichols

00:20:17.610 - 00:20:35.890

Oh, man. So, I wanted to ask you if you're starting a medical device company, what would you do first?

But I'm going to put that question off for a little bit, and I want to dive into that a little bit more. When you say burn it down, let's just say assume we're an established medical device company.

At some point we're no longer lean, or maybe we started out, but we're no longer that way.

Steve Gompertz

00:20:36.050 - 00:20:36.410

Right.

Etienne Nichols

00:20:36.410 - 00:20:40.370

You've seen a lot of companies. So, when you go through that process, what does that even look like?

Steve Gompertz

00:20:41.330 - 00:21:38.560

It's a tough decision, especially if you've already had a quality system for a while and the organization's mature. I've got a company like that, and they've been around for 40 years, and the quality system is about 40 years old.

And it's, you know, they just keep adding pieces onto it. Right. Without any thought to it. And they brought our company in to do their internal audits because they no longer had the bandwidth to do it.

They weren't sure they were being effective at it anyway. And sure enough, every time I go in, I'm just picking it apart.

And at one point, the VP of quality said, it almost seems like it might be easier for us to start over. Yeah. Because there's too many fixes. And again, it's a system.

And if you do it right, it's the proverbial pulling the sweat on the thread on the sweater. Right. You pull and the whole thing comes with it. And they're trying to figure out how to knit the sweater back together. And sometimes, you know what?

Let's just create a new pattern here. Let's start over, right, from the quality manual and then rebuild it. Yeah.

Etienne Nichols

00:21:38.640 - 00:22:12.050

I can see two potential issues that you're facing in that situation. One might be that the quality manual is.

Or the quality system and also the documentation is so, I guess, so much that it's not actually being followed, or it's so bloated and it is being followed that the processes are not really going as streamlined as they could.

And I kind of wonder, you know, if you were, if you're the first one where they're not actually being followed, that would be an easier situation to rewrite everything, I would assume. Or is that. Is that the case?

Steve Gompertz

00:22:12.690 - 00:23:43.840

It's a combination of the two, really. Right. Done correctly, efficiency and effectiveness are not enemies. You can achieve both in quality and in a quality system. The problem is. Yeah.

If they haven't really thought through all those connections, it's tough to envision, and then it's tough to make repairs. Because you don't know when I fix this here, did I just break something else there?

Or even why isn't this as efficient or as effective as it should be? You know, when we do audits, we ask questions like, well, where does that information come from? Where's, where does it go? Right?

Where does the result of your process go? And often they can't answer that kind of stuff because they don't know what the entire system looks like. They know their piece.

I just do this because my procedure says I do this, and I produce this. But they don't know who that they might have a loose idea of where that's going, but they don't really.

And the people that's going to aren't quite sure how to engage with them, to tell them what they really need. And this is the same as we talk about knowing your readers, knowing your customer internally. Right. Where is this going?

It's often funny because when we do sometimes process mapping and we look at certain outputs and then we ask, so who's the customer of that? You know, SIPOC kind of thinking.

And nobody knows, meaning you're producing it because you've always produced it and nobody actually uses that information, you know, or inputs that somebody's expecting. They never quite get them the way they want, but they're not quite sure where they're getting it from. So, they find alternate mechanisms to the do it.

And it's like, this is not a healthy quality system.

Etienne Nichols

00:23:44.400 - 00:23:51.040

Yeah. And just for those listening who aren't familiar. So SIPOC being suppliers, inputs, process, outputs, customer.

Steve Gompertz

00:23:51.200 - 00:23:52.560

Exactly. Yeah, yeah.

Etienne Nichols

00:23:54.080 - 00:24:10.230

I'm curious. So you go, that's a lot of work to, to analyze an entire quality management system. You go through all those different things.

Do you have an easy or an effective way of proving the ROI on a good versus a quote unquote bad QMS?

Steve Gompertz

00:24:13.270 - 00:25:48.360

You know, first. Right. If you want to just do it simply, this isn't necessarily the best metric. But how many audit findings do you get right?

Because audit findings are very, very disruptive, whether they're internal audit findings or external audit findings. And I think it's a, you know, one place I did it. Literally every internal audit produced at least a dozen non-conformances.

FDA comes in four findings on a 483. BSI comes in three majors, six minors and a slew of OFIs. We burn the quality system down, we rebuild it. It takes time. Three years it took, right.

The next time FDA comes in, no findings, BSI comes in one minor. Really, really minor internal audits. They're now again, your internal audits should be hard.

So, it's not that they don't find anything, but before where everything they were finding was sort of like a failure of intent. Now it's more like not necessarily as perfectly effective as we could be. But you're starting to see we have these and more OFI kind of things.

So, I think that's a pretty good indicator that your system is maturing from that perspective. The other thing is to apply a maturity model. I developed one a while back.

CMMI, I think, has now got one related to quality and FDA and the MDIC have now come up with a kind of maturity-based model for that. So that's another thing to look at because they can demonstrate if you achieve certain levels of maturity, you will realize these benefits.

And they have all the data to demonstrate that and examples.

Etienne Nichols

00:25:49.000 - 00:26:03.920

Yeah, okay, that makes sense. When I get into the mind of a quality manager or a VP of quality who's trying to streamline their processes, they have to prove.

A lot of times it seems like they would need to prove the roi because it is a lot of work.

Steve Gompertz

00:26:04.560 - 00:26:54.180

It is. But it's no different than just thinking a quality system as a product that's being developed.

The same way you can't develop a medical device without starting from the requirements and getting that right.

And if you try to shortcut that and just get past it so you can actually start engineering and just dive right in, that's when you start finding things. Don't go right at the end when you get the verification, validation, testing, it's a problem.

When you try to look at manufacturing capability, all of a sudden that's not right because we didn't think about design for manufacturability and all that. Yeah, it seems like a lot of work up front and I don't know, just Google it.

There are gazillion white papers out there that'll tell you fixing things, doing things right at the start makes the rest of it go incredibly faster. You know, it's just not, it's not anecdotal. There’re all kinds of data and examples out there.

Etienne Nichols

00:26:54.420 - 00:27:18.960

I love that you treat it like a design project because I, I've used that in the past and I love that analogy because.

And really, you know, maybe and in some worlds, we need to kind of correct our definition of what engineering is because I think I've been in places where they're just iteratively trying something and trying something and trying, oh, this worked. I'm like, that was not engineering. Engineering is the application of physics and mathematics to correctly solve a problem. Problem.

Steve Gompertz

00:27:18.960 - 00:27:19.320

Right.

Etienne Nichols

00:27:19.320 - 00:27:22.720

You know and not just iterate until something happens to stick.

Steve Gompertz

00:27:22.720 - 00:27:43.440

It's like you always have to remind people, right, everybody has a customer internally, everybody produces a product. The quality and regulatory organization's product is the quality system. So why are you not developing that as a product? Right.

Instead of this haphazard slap on a piece here, slap on a piece their approach.

Etienne Nichols

00:27:44.570 - 00:28:16.380

Yeah, I guess the, the large organization is the part that I'm still really trying to wrap my head around. Is there a way? Two questions. Let me, let me slow my brain down here for a second. Two questions.

First question is how do you detect that maybe you're not bringing in a third-party auditor like some of the organizations that you, you're working with right now, but how do they detect that internally?

Because if they're just used to swimming in the, the, you know, the pot, the pool that they're in, they don't necessarily know the difference one way or another because they're so used to it. How do they, how do they figure that out?

Steve Gompertz

00:28:16.620 - 00:29:26.020

Yeah, it's tough when you're segregated, right. And you've got business units or divisions who don't get a chance to talk to one another.

So, you got to look for those opportunities to find your peers, right. At the other sites and compare.

But in some places where they are a little bit more integrated, you know, look for things like why do we have three procedures that all do the same thing, but the only difference is the site? And then there's these subtle, subtle differences between them or none at all. Right.

So, you're looking for that redundancy in the system where we, you know, why does every site need its own training management procedure? Training management's training management, DOT control. There are just certain things in the quality system that are the same everywhere.

So why do you have separate ones by site when you get down to the work instruction level, like especially in operations. Yes. Right.

If this site is doing more injection molding and this site's doing more stamping, you're right at that level going to be completely different set of documentation. But the way in which you do process validation, probably the same everywhere. The way in which you train the operators should be the same everywhere.

So, I think it's just, you got to just take a step back and go, are we doing any, are we duplicating effort anywhere where there's really no point to it?

Etienne Nichols

00:29:26.580 - 00:29:40.900

Yeah, I want to kind of dive in just a little bit deeper on the Ambiguity or the allowed ambiguity. So, I'll give you, my example. You kind of think about this for a second. So, the regulations are necessarily vague because they apply to everyone.

Steve Gompertz

00:29:41.220 - 00:29:41.580

Right.

Etienne Nichols

00:29:41.580 - 00:30:16.450

And I've used the example in the past. Like if you go around a curve driving your car, it says 45 miles an hour. But if you're, that's not what the FDA does.

They don't put up a 45 mile per hour zone. They put up a, it's a 15-degree grade with this surface friction and these conditions.

And, and then if you're a semi, you back calculate, oh, I better go 30, or if I'm on a motorcycle I can go 60. Depending on your organization. You apply what you're doing to the regulations and that ambiguity is necessary.

So, I'm curious how that could trickle down to our sop. Maybe, maybe I should ask if you agree first. But I'm curious about the ambiguity in our sop.

Steve Gompertz

00:30:16.450 - 00:30:28.210

I do.

That's part of my thinking on the lean approach is be careful of being overly prescriptive because like you said before, it becomes just a trap for audit. You know, again, I don't like to focus on what the auditors are going to say.

Etienne Nichols

00:30:28.290 - 00:30:28.610

Right.

Steve Gompertz

00:30:28.610 - 00:31:46.120

It becomes a trap for.

It just creates an increased chance that somebody's not going to do it because now there's too many specifics to remember when you get to certain levels in the quality system. Like I said, when you're down in the operator level, you're down on the manufacturing floor. Yes. It's got to be very prescribed.

We need it to be repetitive. Right. Reproducible, repeatable, that kind of thing. And we want it done a certain way.

But if I'm telling you to fill out a document change request, other than teaching you how to use our eQMS, you know, what button to push. I should explain what goes in the impact field, but I can't hold your hand and write the words because I don't know of all the possible impacts.

You need to describe that. Right. So, it's give examples. Now this is also where guidance documents come in.

And that can be controversial in organization, whether or not that quality system structure includes guidance off to the side. But that's where it has value, saying, look, there are options to doing this. There isn't just one way. Here's a recommended way.

We're not going to make you do it right. But whatever you do, make sure you at least establish the guardrails, as you call it, before you have to at least fit within these constraints.

You're going to have to provide this type of information. How you provided is up to you.

Etienne Nichols

00:31:47.320 - 00:31:57.390

I really love that you brought up guidance documents. This is a little bit new to me for incorporating them into an organization. What does that look?

I mean, I'd even love to hear about the controversy behind it. The pro and the con.

Steve Gompertz

00:31:57.390 - 00:33:55.270

Yeah, it's. It can be. Some companies. Absolutely not. We will not have guidance documents. Right. Because they get abused and people try to hide stuff.

That should be requirements in there. Okay.

Other people overuse them for exactly that reason, going, well, if we put it in the guidance document, we can't be audited to it, which is a myth. Whatever you're doing, you can be audited because the auditor is just going to ask, so what decision did you make here? How did you decide to do this?

Right. Well, I followed what was in this guidance doc. Great. Tell me about what you did. They're not really auditing the guidance.

They're auditing what you did and whether it made sense and whether you made the right decision. So, I think they're really useful because, yeah, there are times when there are options. Right. Or there's.

One of the examples I use is in good documentation practices, a lot of times companies don't have a good way to explain to people how to do proxies. Right. I'm going to be on vacation. I want you to sign for me. How do I do that? Okay. Now, one thing you can do is I've done this.

I put a form together to do that. Okay. But that isn't a requirement. The form is an example. If you cover these pieces of information which happen to be on the form.

So, if you want to use the form, it's easy. But if you can cover those same pieces of information in an email, you're still valid. You're still doing what we need you to do.

There's lots of stuff like that on a quality system where you go, there isn't just one way. Now, if you, if you absolutely look at something, you go, in our business, we've decided it has to be done this way. For whatever reason, that's fine.

But that doesn't mean everything has to be that way. Sometimes you do want to, as the same as the FDA and other regulatory bodies do they leave some wiggle room in there, right.

So that you can make sure it matches what you need. Right. And how you operate.

As long as you're prepared to rationalize that and explain it, which should be built into the process, that there's a point at which you Capture. Why did we do it this way and not this way?

Etienne Nichols

00:33:55.830 - 00:34:24.440

Yeah, it makes me think of principle versus react. Well, not sure if that's the way to describe it, but a lot of rules are put in place because someone broke something or messed something up.

So, it's like, well, we're going to put a rule so that never happens again.

Well, it turns out if you have a rule break or a, rather a rule breaker or just some, someone who is, I don't want to say incompetent, but, but just that's not the role they should be in perhaps. And they're, they're continually doing, you're just going to be continually laying on rule after rule.

Steve Gompertz

00:34:24.520 - 00:34:25.000

Yeah.

Etienne Nichols

00:34:25.080 - 00:34:27.960

And, and it becomes kind of bloated in that way to it.

Steve Gompertz

00:34:27.960 - 00:35:02.460

So, this could be a whole other podcast as well. But what you just touched on there, where we add it because somebody made a mistake, that's lazy root cause analysis.

Actually, it's not root cause analysis. That's fingerprint symptom. And the easiest way was to patch up the sop. That doesn't explain why it happened. Right.

There's, there's something deeper that occurred that allowed it to happen.

You need to figure that out and then figure out which process actually, because it could, it may not be affixed to the process where it manifested itself. It might be in a completely different process. Process.

Etienne Nichols

00:35:02.940 - 00:35:04.380

Yeah, yeah.

Steve Gompertz

00:35:04.940 - 00:35:07.260

That happens a lot in my, in my world.

Etienne Nichols

00:35:07.580 - 00:35:30.940

You know, how else do companies become a little bit more bloated you mentioned?

And I, I, I really like the example of multi sites that they have a procedure for each individual site when it could be just one to govern both or, you know, three, four, whatever sites. What are some other things? Let's say it's a single site organization.

Are there other issues that you kind of see as common pitfalls that companies get into?

Steve Gompertz

00:35:31.480 - 00:35:40.120

Well, I think it's what I was just talking about. Right. Not wanting to do a real root cause analysis and the easy fixes. Yeah, slap another section in there, Slap another requirement.

Etienne Nichols

00:35:40.520 - 00:35:41.080

Yeah.

Steve Gompertz

00:35:41.160 - 00:35:47.399

There. And we're good right now. We've trained; we retrained everybody because retraining is absolutely the best way to fix your quality system.

Etienne Nichols

00:35:49.000 - 00:35:52.680

The third mitigation in line from ISO 14971. But whatever.

Steve Gompertz

00:35:53.160 - 00:36:07.920

But I, I think that more often than anything else is what drives it is just, you know, too quick of a fix to just throw another requirement in there. And then you just keep creating this bigger and bigger document that's just creating more opportunity to make a mistake.

Etienne Nichols

00:36:08.240 - 00:36:25.070

So, for that Specific issue then.

And you go in, you see, oh man, they've just layered on problem after problem or rule after rule because someone was making mistakes or whatever the case may be. How do you peel back that onion to really just cut the fat in that situation, it comes back to process design.

Steve Gompertz

00:36:25.070 - 00:37:21.590

You got to step back and go, let's reanalyze this process. What is the intent of this process? Right. How is it side by what feeds it? What is it? Well, you start actually on the opposite side, right?

What does it have to produce? Okay, how is it going to do that based on how it's going to do it? Then what do I need for inputs? Reanalyze it and start to see those connections.

And then it usually becomes more clear which of the details are needed and which are not. And you know, and I get it, people get nervous going, well those five things are in there because of five CAPAs over the years.

You know, if you remove them, we've just negated those CAPAs and it's like time moves on. It's time to rethink this.

Just because you made a change, you know, because of a CAPA four years ago doesn't mean that that's now etched in stone and can't ever be changed again. And frankly, I go show me that CAPA and I bet I could rip it apart and tell you did the wrong thing anyway.

Because cap is another one of those processes that people just don't get. Right.

Etienne Nichols

00:37:22.390 - 00:37:48.300

Yeah. Well, let's go back to quality manual then. I'd love to see maybe an example CAPA procedure from you at some point.

But you've talked to me about your example quality manual, and we've talked about this in the past, but I've actually seen people, we saw them on LinkedIn. Someone was saying, yeah, that was awesome. We took your example, we ran with it, we successfully gone through an audit. That was fantastic.

So, let's just mind running through that story real quick.

Steve Gompertz

00:37:49.020 - 00:38:40.550

Yeah. So, you know, I, I got to a company as the head of quality and had been there a week and an audit was happening.

So, you know, I've been through audits before. I didn't, you know, I couldn't really enter answer details around the company, but I had the people I would need.

But first thing you do is you have the opening meeting with the auditor and of course inevitably they say, can you give me a copy of your quality manual? Right. And I slide across this 47-page monstrosity which he picks up in his hand.

You know, like the old joke about Your college professor weighing you for your grade, weighing your paper for grade. And he just kind of held it in his hand and he looked across the table at me and he went; this was a 9001 audit.

And he looked at me and went, how many requirements are we satisfying? And I went, four. And he goes, okay, I just want to make sure you knew.

Because I wasn't quite sure why a document this big was needed to satisfy four requirements.

Etienne Nichols

00:38:40.870 - 00:38:42.510

10.25 for each.

Steve Gompertz

00:38:42.510 - 00:39:24.440

Right? Yeah, there we go. You know, and I just said, hey, I just got here last week, I'm going to fix this jump ahead.

You know, a year or two later and another auditor sitting across from me, this one actually might have been FDA, if I'm thinking about it. I think it was actually FDA. Same thing. Do you have a quality manual?

And now instead I hand them this famous thing that you've seen my favorite brochure, quality manual. And I just handed it to him, and he looked at it. Open it up real quick. Anyway, finally somebody figured it out. This is all it needs to be.

Etienne Nichols

00:39:25.720 - 00:39:27.560

Trying to spread the word. That's fantastic.

Steve Gompertz

00:39:27.560 - 00:39:33.090

Quality system Pyramid. Right. The smallest piece is the quality manual. So why is it the biggest document?

Etienne Nichols

00:39:35.010 - 00:39:41.330

So, some people want to make the argument that you need to reference every other SOP in there. How do you handle that? Or what do you.

Steve Gompertz

00:39:41.650 - 00:42:08.100

You just need a map. You don't need to. Well, you don't need to include the content from all those SOPs. Right. If the idea is, yes, I have a control SOP.

I have a design, controls SOP. Fine. You just need to point to them, and all the details will be in there. Don't start repeating stuff.

And typically, what gets repeated in the quality manual is just the parroting back of the standard and the reg anyway. Right. Where the standard of the reg says, the manufacturer shall. And you write XYZ Corp. Will, that did nothing except say you saw it. Right.

Point to the procedure the procedure is going to get into. And here's how we are doing that. Right. But the quality manual just needs to say, yes, we have a procedure for doc control. You'll find it here. Right.

That's. You know that diagram I've got on the inside of mine is the procedure process map. I know it's hard to see. I was practicing before. There you go. Right.

Each of those boxes points to another document, right? Yeah. From here I can see all of the major processes that make up my quality system. That's all I need at this level. It's a map. Right.

For the rest of the system where this comes from is there was, there is still a guidance document, it's very old now from FDA that gets into how small entities can conform.

And there they allowed for this possibility that look, yeah, you're, you're a small entity, you have like 10 people, you don't have a dock control department. You know, you don't have the bandwidth to manage all these SOPs.

So, it was okay to create a quality manual that happened to be the entire quality system. And I went to one place like that as a supplier audit when I asked for the quality manual. So, well, we'll give you the whole quality system.

And I didn't even know they made binders this big. But every part of their doc, it was one document, and every chapter was part of the quality system. And I got it right because quality was one guy.

There wasn't a dock control department. They weren't managing 100 sops and 50 work instructions, just this big document.

And that was meant for small entities for some reason though, larger entities that have the bandwidth and the capability to create a hierarchy and have multiple documents and have specific document owners or process owners still took on that model and then also added on all the separate SOPs. And so now they're trying to manage both. And of course, we know what happens when we have the same information in two or more places.

It will diverge at some point. And now they're both, they're going to say conflicting things.

Etienne Nichols

00:42:08.660 - 00:42:28.980

Yeah. All right, so we talk a little bit about some of the bigger companies and the problems they face.

What about a company that's just getting off the ground? I think, I think we talked, I mean, we kind of covered it, the design, design thinking.

But if you were starting a medical device company, maybe, maybe in, more in the nitty gritty, what would you do first? Would you.

Steve Gompertz

00:42:29.060 - 00:43:59.090

Yeah, we, and we do this a lot because we, we do focus a lot on smaller and early-stage companies. And yeah, they don't need the entire quality system.

And there's no requirement that you have a complete quality system, even up to the point of submitting like a 510k to FDA. After that you need to have a complete system. But early stage, right, they just have a concept. They haven't even built any prototypes yet.

So, they don't need supplier controls, they don't need process controls, they do need design controls. And since if it isn't documented, it didn't happen. First things first. Document and records control is always going to come first.

Along with that is good early on, get management responsibility figured out what that's going to look like, particularly review and monitoring. Right. What are you going to look for? But then, yeah, design controls are usually first.

After that, then you're probably going to go to, you know, typically you're not going to build a factory as a startup, you're going to go out to a contract manufacturer. So now I need supply controls, supplier controls. Right. Purchasing, that would be next.

And then, you know, if they continue to always farm it out, the. They won't ever need process controls.

But at some point, they go, well, now we're going to be big enough, we're going to bring that in house now, you know, so it's meant to be built over time.

It's an evolution, you know, but early on got to have design and record or document record controls and you got to have design controls and it's usually good to establish management responsibility at the same time.

Etienne Nichols

00:43:59.650 - 00:44:05.730

Okay, what does management responsibility look like in your mind? I'm just, that's kind of a thread that I just.

Steve Gompertz

00:44:05.810 - 00:45:05.840

Yeah, well, it's, it's mostly going to be about so who's responsible for what, who's, who's management with executive responsibility, who's the management rep, those kinds of things. If you're in the EU, this might be a good time to figure out who's your person responsible for regulatory PRRC. Right.

So, you're just establishing more of the roles and start establishing what's going to be our cadence for reviewing what's happening. Right. So managed review starts to creep in. Yeah.

Obviously again, you don't have a complete quality system yet, so you can't meet all of the requirements for management review. But you can get it started and go, well, what would management review look like for us now? Right. How are we going to do that?

Is it a singular review or is it made up of a bunch of sub reviews that then once a year we aggregate that up into one final review for the year or something.

There's a whole bunch of ways to slice and dice it, but it's just establishing that those roles and the structure of management of the quality system.

Etienne Nichols

00:45:06.240 - 00:45:36.950

Yeah. Well, I want to go to another thing that you had said earlier when you said you, I could probably take your CAPA, you know, SOP and terrorist maybe.

I'm curious what you see. Is it typically wrong?

Because when you talk about, when you look at the, the, the typical findings from the fiscal year that the FDA publishes, it's always CAPA number one, design controls, complaint handling. So, what is up with CAPA and their SOPs.

I mean, yeah, we talk about CAPA from a theoretical standpoint but is there something specifically that we're not.

Steve Gompertz

00:45:36.950 - 00:47:42.830

Yes. I just want to clarify what I said earlier. It isn't that I will probably be able to shred somebody's capital procedure.

I'm going to be able to shred their CAPAs that come out of it.

And that's what you see a lot of in these, you know, FDA citations is companies will, I mean CAP is one of those places, especially within, you know, the FDA regulations where they're, they are very prescriptive about what you're supposed to do. They give you the seven steps right there. So, companies often have that figured out. They have a really good procedure.

What happens is there are never any CAPAs. They don't know how to find them. Because CAPA is not a standalone process.

It's tied into your process and product monitoring your complaints and feedback. There's a whole bunch of other processes that have to feed it. And they've not defined the feeders, right. And, and it's bidirectional.

It's not just saying within the CAP process where do I expect to get CAPAs from? It's then for, you know, I always do this, I go, fine, show me that.

And if they, if they're smart, their CAP procedure lists the feeders, then I want to see the feeder SOPs and say, do they mention CAPA? And how you, when and if you go to cap? And usually that's missing, right? So, it's just, there's nothing feeding the process.

And if it is, if they do have CAPAs, there's the overuse, right? There's the old death by CAPA where we now treat CAPA as if it's the non-conformance management system, which it's not.

It's supposed to be for systemic and high-risk issues. And then when you look at the information they're capturing, you know, there's not complete descriptions.

They don't understand the concept of root cause. They confuse apparent causes with root causes. They don't really do a deep enough dive.

They don't understand the difference between corrective action and preventive action, which are mutually exclusive by the way, or correction for that matter. And too often they state, you know, on in the corrective action section, it's a bunch of corrections which are fixes.

Retraining is not corrective action. Retraining is correction. You still need to define what your corrective actions are.

So, it's, it's usually those things that just how it Manifests itself is just. It's bad on the execution.

Etienne Nichols

00:47:43.230 - 00:47:43.710

Yeah.

Steve Gompertz

00:47:44.190 - 00:47:58.110

And. And picking the root cause, you know. Oh, yeah. Operator error. Insufficient. Insufficient training. Oh, my gosh. Okay. You know, those are not root causes.

Those are symptoms, you know.

Etienne Nichols

00:47:58.990 - 00:48:25.190

Well, okay, so you mentioned the bidirectional linking, and I like that a lot. I'm curious about the root cause analysis. How can we do a better job than. And I've kind of wanted to talk about this for a while, so it's kind of.

I don't mean to derail our conversation, but what about taking the root cause off into its own SOP or, you know, the layering that you said? What do you. Is there a way we can have our documentation work better for us in this. In this sitting?

Steve Gompertz

00:48:25.190 - 00:49:04.740

Yeah, I think that's so one. I don't think we give them a complete tool set typically. Right. We talk about. All right, here's where you have to find root cause.

And maybe there's a little bit of mention of that. And we're going to put in the five whys, because that one's easy to explain really quickly in a document. That's a tool. It's not the only tool.

It's essentially brainstorming, which again, is a tool, but not the only tool. There are multiple tools. You need just, you know, it's the old. You know, I think it was. What was his name? Maslow was the psychologist. Coin.

Whatever the official phrase is, but we've turned it into. Right. If. If the only tool I have is a hammer, every. Every job looks like a nail. And he said it differently, but he did say that.

Etienne Nichols

00:49:05.210 - 00:49:06.370

I didn't know that was Maslow.

Steve Gompertz

00:49:06.370 - 00:49:12.970

Okay, it is Maslow. Yeah. Yeah. That's one of his other things. That was actually how I first came across Maslow. And I went, oh, he's got a lot of other good stuff.

Etienne Nichols

00:49:13.610 - 00:49:16.130

I just. The. The hierarchy of needs. Isn't that right?

Steve Gompertz

00:49:16.130 - 00:49:22.570

The hierarchy needs, I think, is probably his most famous thing. But he did. Yeah, he did make the quote about the hammer and everything looking like a nail.

Etienne Nichols

00:49:22.890 - 00:49:26.970

For some reason, I thought that was my dad. You know, who has a hammer? Everything's a nail.

Steve Gompertz

00:49:26.970 - 00:50:31.570

I'm like, but it is fun. We don't. We don't train people on. So, what are the tools of root cause? You know, analysis and how to use them.

You've got to use, like any other quality problem. You're not going to solve it with a single tool. They.

There are multiple tools that have to play together, which means you understand how they play together. And you have to get away from your biases, which are towards what did I see? Which is just. That's the apparent cause.

And often, as I've said, just because it manifested itself here might not mean that that's where the problem actually started. It probably started somewhere else in the factory or in the plant or in another site, another part of the business that led up to this. Right.

Then there's a question of, okay, did we strip across it or did we have the right controls in place to find these things? Again, the feeder process, it's complex.

Everybody wants to go as simple as possible, that there's got to be a single tool, a single procedure, you know, a single form that I can fill out that'll solve all my problems. And you're ignoring that word system. You can't ignore that. It's all interconnected.

Etienne Nichols

00:50:32.210 - 00:50:45.530

And that's a perfect example, too, of the document that may be perfectly laid out. Because you mentioned the. The FDA is pretty prescriptive about how it should look and probably fly through an audit pretty well.

As far as the document itself, when they.

Steve Gompertz

00:50:45.530 - 00:50:45.890

Right.

Etienne Nichols

00:50:45.890 - 00:50:54.200

CAPAs themselves are a different story, obviously, as shown by all of the. The reporting that the FDA does on their findings.

Steve Gompertz

00:50:54.360 - 00:50:54.760

Right.

Etienne Nichols

00:50:54.840 - 00:51:00.600

But it's a good example of a potentially good document not really doing the job that we're looking for. Yeah.

Steve Gompertz

00:51:00.600 - 00:52:18.690

And it always comes down to, you know, like when people say, hey, I want to get training on this reg or this standard. Do you have a course you recommend? I usually recommend take the auditor's version of that and understand how they're going to look at it.

Because there's three things that an auditor looks at and in this order. First, did you understand the intent of the requirement?

So, did you write the procedure, and did you correctly interpret the requirements in the procedure? Great. You have the procedure. Is anybody following the procedure, and are they following it correctly? Right. So, then it's execution. Is that correct?

Great. And then, okay, fine, you have the procedure. People are following the procedure. Does it work? Effectiveness is that last piece.

And so more often than not, in those statistics you see from FDA, intent is being met. Execution. Mostly it's the effectiveness that they're pinging everybody for. You're not feeding the process.

You're not getting the true, correct or true root causes, which means you're not actually addressing the proper corrective actions and therefore are not likely to prevent recurrence, that kind of thing.

And then the other thing that's always left off is, you know, you go through somebody's spreadsheet or wherever their table is for managing their CAPAs. And there's always that field saying, was this a correct a CA or a PA. Yeah. Is never checked.

Etienne Nichols

00:52:18.690 - 00:52:20.850

You never see one? Nope. No.

Steve Gompertz

00:52:21.250 - 00:52:40.370

Right. We love Fight being firefighters. We love playing whack a mole.

And they forget take credit for all the things you do to head stuff off because you do it. I'm sure it's there. Right. It's just we never think to take it through the process.

But part of that problem is, of course we use the term CAPA, and it sounds like it's a single process and it's not supposed to be a single process.

Etienne Nichols

00:52:40.930 - 00:53:28.220

Yeah. Well, this has been great. I really appreciate all of the tips you've given around Lean Documentation.

And I'll also mention to those listening that we've done one in the past where we talked about guerrilla tactics and on how to sneak stuff into your quality management system so that people don't think, oh, we're implementing an agile process or a lean process or whatever. So those are cool. And I'm going to put those in the show notes too.

So, if you want to find those other conversations we've had with Steve, I'll also mention the Quality Manual. He's provided that as an example. It's a PDF in the community, so I'll give a link to that as well.

So, you can find that if you're interested in learning more about that. But what have we missed? Is there anything you would like to talk about?

One last thing with Lean Documentation before we shut it down, you know, something.

Steve Gompertz

00:53:28.220 - 00:53:30.260

Had just gone into my head and then it went right back out.

Etienne Nichols

00:53:32.740 - 00:53:34.100

It needs to be documented.

Steve Gompertz

00:53:35.140 - 00:54:03.900

Yeah, right. I should have been writing down notes because, yeah, now it isn't going to happen because I didn't document it.

You know, again, it's just you've got to pay attention to that word system in quality System, that that's where the key is.

And so, if you've never read it, go read section 0.135 where it talks about process thinking and the process approach and live it and breathe it and yeah, you'll get a better-quality system from it. Great.

Etienne Nichols

00:54:03.900 - 00:54:13.780

Thanks, Steve. Looking forward to seeing you a few weeks.

I'm planning to be in Minneapolis in May, and so if anybody's listening, you're able to come to the true quality road show. We'll be there as well. So, I assume you'll be there.

Steve Gompertz

00:54:14.580 - 00:54:18.420

I gotta make sure it's on my calendar. I got a busy May, and I don't remember if I've got it.

Etienne Nichols

00:54:18.420 - 00:54:20.900

I understand. Well, I'll try to hunt you down one way or another where you're at.

Steve Gompertz

00:54:20.900 - 00:54:22.020

Yeah, make sure I've got that.

Etienne Nichols

00:54:23.140 - 00:55:35.250

All right, well, cool. Thank you so much. And yeah, we'll see you all next time. Thank you so much for listening. I hope this was beneficial.

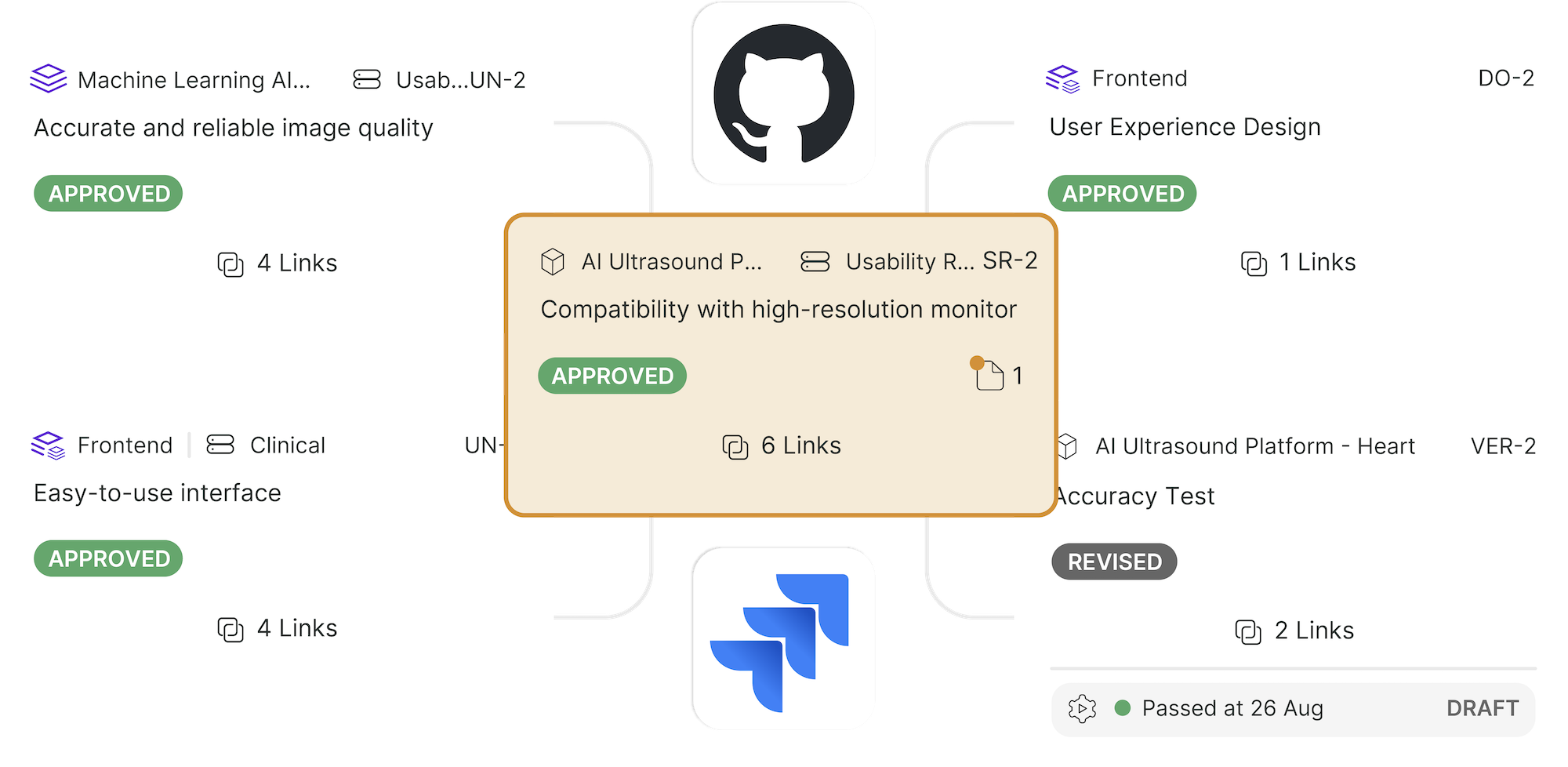

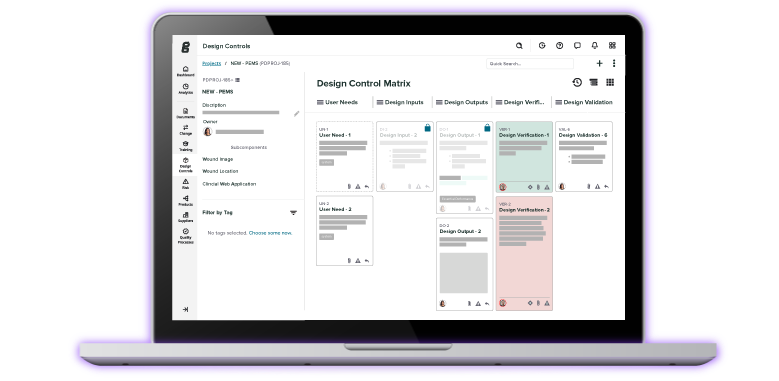

If you're interested in learning about more quality management systems tools such as the software that we built for our MedTech specific companies out there, document management system, our CAPA management system, our design controls risk management system, which includes a certain portion of AI now in risk management. We're turning the world upside down there. Or our EDC software. You can check that out at www.greenlight.guru.

Finally, please consider leaving us a review on iTunes. It helps others find us and it lets us know how we're doing. As you can see, I have forgotten how to speak. It's the end of the day.

I'm going to get out of here. Hope you do, too. Have a good rest of your day. Bye. The best medical device companies don't just follow the rules. They lead with quality.

At Greenlight Guru, we try to do the same.

Our medical device success platform is based on the latest FDA and ISO standards as well as the best practices of medical device manufacturers who lead the industry with products of the highest quality. If you're ready to bring safer, better medical devices to market faster, contact Greenlight Guru today.

About the Global Medical Device Podcast:

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Etienne Nichols is the Head of Industry Insights & Education at Greenlight Guru. As a Mechanical Engineer and Medical Device Guru, he specializes in simplifying complex ideas, teaching system integration, and connecting industry leaders. While hosting the Global Medical Device Podcast, Etienne has led over 200...