What Medical Device Developers Should Know About Human Factors

Human factors can be a topic rife with confusion for medical device developers. What do they mean? Why are human factors included in regulations?

I recently caught up with Bryant Foster, Vice President of Research & Design at Research Collective and an excellent resource on the topic of human factors. Bryant’s work involves applying the principles of cognitive psychology to the design of new technologies, a practical use of human factors.Where different functions intersect

One of the confusing issues for medical device developers is often around the differences, overlaps, and intersections between human factors, design controls, project development, and research and development.

Human factors really come down to good design practice. Someone is going to have to interact with your product regardless of what you make. The human factor is about taking the user into account - where they work, what they work with, the space they have available and the things they are proficient or unskilled at.

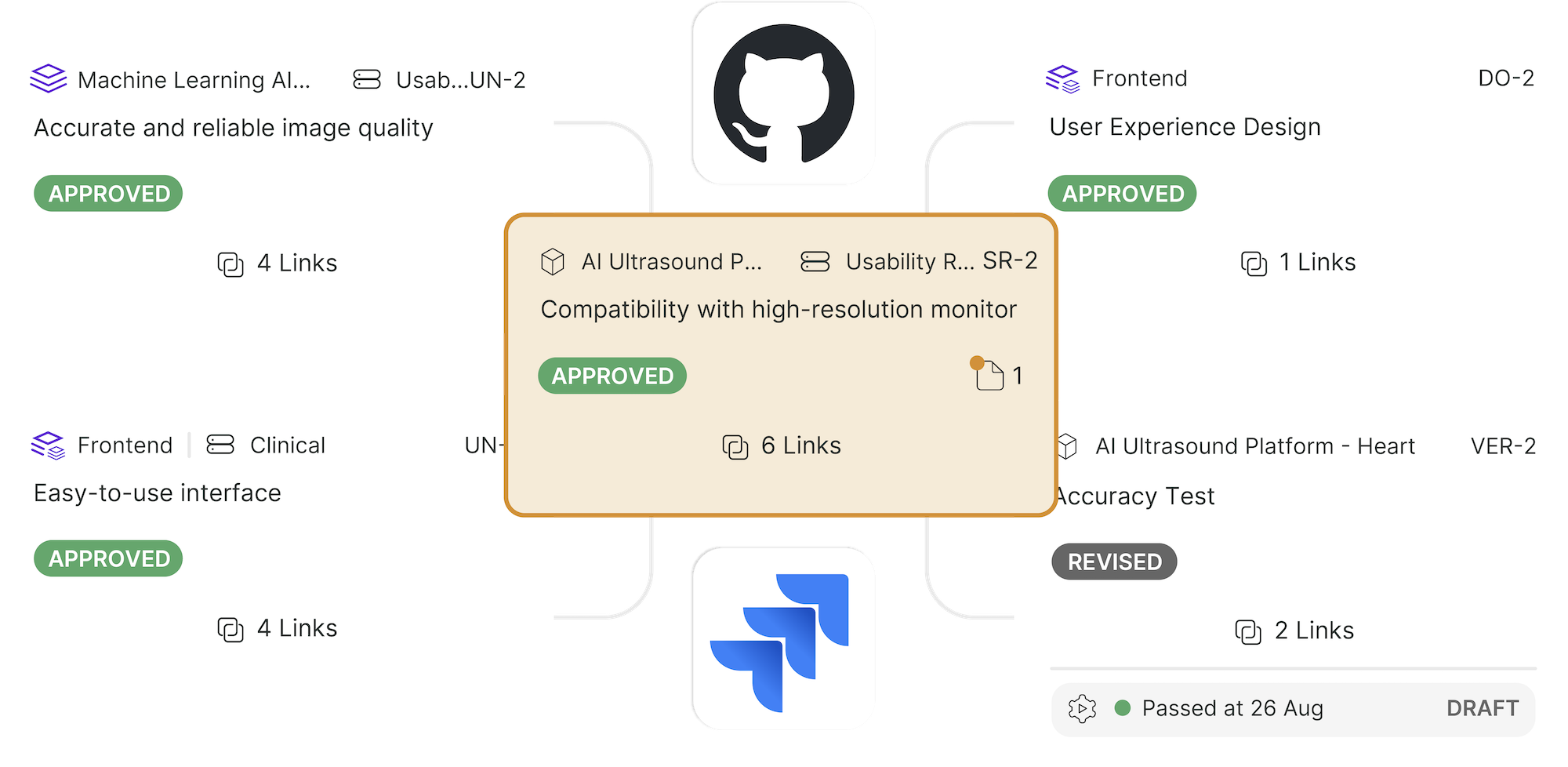

When it comes to your design controls, human factors is about usability. You need to make sure it does what is intended, and users can use it how you intended. As far as the link between design controls and human factors, AAMI recently put out a great report about integrating the two, which you can access here.

Companies often seem to fall into the trap of looking at each of the different quality functions they have to manage (design controls, design validation, risk etc.) as separate buckets. In reality, everything is intertwined and human factors is an important part of each. Gone are the days where slapping a label onto something was good enough for providing users with a working product - we have to ensure that usability is addressed.

Risk assessments and task analyses should work together. While the risk assessment covers the engineering side and task analysis assesses what users need to know to use the product, they really work hand-in-hand. An example Bryant gives is an engineering feature that renders the product unsafe if wet, working with task analysis, you then ask how do users know not to get the product wet?

How should companies address human factors?

Let’s say you’re up to your eyeballs in quality and regulatory requirements, perhaps preparing for a 510(k) submission. Human factors is often the last thing on your mind, so how should you address it?

Bryant’s first recommendation is don’t wait any longer! One of the things they do quite often is GAP analysis in regard to human factors. They come in, make an assessment and look at usability testing. Can the device be used as intended? Bryant says this is unusual right away, so they work on getting a small study of users together in order to learn where the baseline is, and how the device interface and/or supporting material might be changed to help.

By the time you submit to the FDA, it’s too late. Factor in human factors early on!

Common human factors mistakes to avoid

One of my early mistakes as a medical device product engineer was taking a cocktail napkin sketch from a doctor and trying to quickly go from that to a prototype. We iterated back and forth with each other, went through the 510(k) and got the product to market, where it hit with a thud.

My mistake? I designed the product for one person - I didn’t have the human factors data to prove I had a scalable product.

This all could have been avoided with early human factors analysis and testing. Bryant advocates a “shut up rule” - let them use the device as they see fit, and learn as much as you can from them. The user is the most knowledgeable person about what they want and need the product to do. We’re often quick to want to jump in with solutions, but it’s better to sit back.

Human factors in usability and ergonomics

Our industry has not done a very good job of defining these things, or perhaps in marketing the role of human factors. Human factors is the overarching principle of how humans relate to things.

For ergonomics, you’re going to get a different definition in Europe, but here in the US, it is defined specifically for physical products and design. This might include things like posture or how we use our hands.

Usability is a method used within human factors to understand how people interact with a specific product or technology. Usability has formative tests or evaluations that we do early on. So, if you have a prototype, you might mock it up quite quickly and have people go through tasks for that, so that you learn how they operate.

You lastly get to a validation or summative test. This is when you have what you think will be your final design. You’re not looking to learn anymore, you’re simply looking to ensure that the product can be used by users correctly. This validates the usability of the design.

Task analysis

Task analysis is a user-centered approach to the design of the product. What are all the tasks that a user or multiple users need to do in order to use the device correctly? This includes everything from unboxing, to cleaning, or reprocessing the device.

Bryant describes that they go deeply into each part or sub-task. For example, turning a device on might not be as simple as it sounds. The user has to get the device out of the box, know where the on button is, know that there is a power button, then understand or be able to physically turn it on. When you break a task down like that, you can then look more closely at the “why” when a user says there was a problem. For example, if they couldn’t turn the device on, what was the root cause of that?

This analysis hopefully informs a better design. The aim is that it is as close to what people expect as possible.

We often seem to leave risk assessments as a “later” activity, but this really outlines why it would add value early on. It’s very important from a human factors standpoint to address design features and use as a tool to mitigate risk throughout the process. Bryant says their task analysis quite often points out things that should have been included in the risk assessment, but weren’t.

Why it’s important to consider your users

How often do we consider that our product might actually work its way through multiple users? For example, think about a hospital environment. You might have a completely different person who receives the product and takes it out of the box from the person who actually uses the device in a procedure. From there, someone else again may be doing the reprocessing. Your assessments need to cover all possible users.

Human factors and post-market usability

What should we be doing with monitoring post-market usability? Bryant says that they sometimes hear manufacturers just wanting to “get through” usability as part of the path to market, but really, there’s a lot more to it.

Once you have a device on the market, you’re now monitoring for feedback in the form of complaints, incidents, or risk-related issues. As we’ve talked about before, risk management is a whole product lifecycle activity. Bryant points out, some of those issues that come up just may be related back to usability, so human factors still play an important role post-market.

This is about being proactive and preventive in nature. Where can you take action before things turn into big problems? The goal is to make products that improve people’s lives, and ensure that the device does what it’s meant to be doing. Once it’s on the market, that’s when you can truly understand if it achieves those goals.

This all relates back to the strong practices we promote through the Greenlight Guru blog and the Greenlight Guru Software. Take having a solid quality system seriously, and understand the importance of human factors as a principle that underpins those quality functions. After all, our goal is always to bring safe, effective products to users that solve a key problem for them.

About Research Collective

Research Collective primarily does human factors research, with a main focus in the medical device space. They do a lot of usability studies in the course of their work, and other research involving humans, particularly people using any sort of technology. Their role is to be as knowledgeable as they can about how humans use and interact with things. The company is made of people who have expertise in psychology and technology.

P.S. We hosted a webinar with Bryant on demystifying FDA’s human factors guidance. You can access it here.

Jon Speer is a medical device expert with over 20 years of industry experience. Jon knows the best medical device companies in the world use quality as an accelerator. That's why he created Greenlight Guru to help companies move beyond compliance to True Quality.

Related Posts

3 Tips For Incorporating Risk Management During Medical Device Product Development

5 Tips for Medical Device Engineers on FDA Design Controls

The Ultimate Guide To Design Controls For Medical Device Companies

Get your free resource

7 Tips for Incorporating Human Factors into Device Design