Understanding the Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) Process

Does your medical device qualify for an investigational device exemption (IDE)? What does this process involve and what does FDA expect of these manufacturers? There is plenty to consider when it comes to the IDE timeline and process.

In this episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast, Jon Speer talks to David Pudwill “Mr. Regulatory” who sheds valuable light on the topic of IDE, which allows an investigational device to be used in a clinical study to collect safety and effectiveness data, and how to navigate this process in an efficient and compliant manner.

LISTEN NOW:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some highlights of this episode include:

- FDA has a few programs to consider when it comes to safety and significant risk or not for products. High-risk devices could fall into a non-significant risk study.

- Exempt or not? Make sure to provide sufficient information to identify significant or not risks based on objective evidence.

- COVID-19 issues prompted FDA to post guidance on statistical considerations, confounding factors, and remote monitoring for IDE and clinical studies.

- When does FDA require an IDE? If it’s a new device category or significant departure from the existing technology, FDA will probably need clinical data.

- All PMA devices do not require an IDE. Also, a device that follows the 510(k) path does not require clinical data, but an IDE may be requested with a clinical study for marketing submissions and reimbursement.

- The contents of an IDE application must include 12 items, such as the name and address of the sponsor; a complete report of prior investigations of the device and an accurate summary of those sections of the investigational plan; and a description of the methods, facilities, and controls used for the manufacture, processing, packing, storage, and installation of the device.

- Within 30 days, the FDA is expected to give a decision on the submission. The study will be approved, approved with conditions, or disapproved.

Links:

David Pudwill (Mr. Regulatory) on LinkedIn

FDA - Requests for Feedback and Meetings for Medical Device Submissions: The Q-Submission Program

Investigational Device Exemption (IDE)

Podcast - An Introduction to FDA’s Regulation of Medical Devices

Humanitarian Device Exemption (HDE)

Breakthrough Devices Program (BDP)

Early Feasibility Studies (EFS) Program

EFS Breakthrough Device Designation

Safer Technologies Program (STeP)

Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) Learn

Institutional Review Boards (IRB)

Significant Risk vs. Non-Significant Risk for Medical Devices

Greenlight Guru YouTube Channel

MedTech True Quality Stories Podcast

Memorable quotes from David Pudwill:

“Everybody wants to be breakthrough, but not everybody is breakthrough.”

“There are a lot of clinical studies that are just exempt from IDE regulations.”

“Even high-risk devices could fall into a not significant risk kind of a study.”

“There’s always a chance that the FDA is going to disagree with you, if you think it’s non-significant risk. FDA is going to lean, in general, towards a slightly more conservative judgement on gray area issues.”

“Specifically, if it’s a new sort of category of device or a significant departure from the existing technology, you’re probably going to need clinical information.”

Transcription:

Announcer: Welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Jon Speer: Welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast now on video. Don't worry if you've been listening to the audio. Keep doing it. It's fine. If you want to check out the video, enjoy. On this episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast, I get to catch up with Mr. Regulatory, David Pudwill, and we talk about IDE, investigational device exemption. So, get into a lot of details on this, but it's really good stuff especially if you're considering or want to know more about whether or not an IDE is going to be necessary or the type of path that makes sense for your product. So, enjoy this episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast. Hello, and welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast. Yes, that's right on video. That's a new edition. Folks, listening to the audio version, you're still going to be able to catch that wherever you're listening to the podcast, but be sure to check out the video. We're putting it out and the usual suspects as well, but joining me today on the Global Medical Device Podcast is a recurring a familiar voice Mr. Regulatory, David Pudwill. David, welcome.

David Pudwill: Hey, thanks for having me.

Jon Speer: I've known this, and, hopefully, people have already picked up that at least we have the same hair stylist. But, folks, go to YouTube. Type in Mr. Regulatory. David's got a ton of content that's there on a lot of things, FDA related. And today, we're going to dive into one of those conversations. We're going to talk about IDE. So, I guess before we get too deep, David, it might be a good place to start, what is IDE? Some folks may know, but don't make an assumption here.

David Pudwill: Yeah. It's one of those FDA acronyms. Oh, wait that's another one. The US Food and Drug Administration terms an investigational device exemption as an IDE, usually, this is a clinical study that you need to get in front of FDA, and that's the submission mechanism that FDA has put in place for you to go ahead and submit that information and for them to approve or disapprove your clinical study.

Jon Speer: Okay. And, folks, there are a ton of resources and links, and we'll share some of those and the text and the show notes that accompany this, but a lot of information out there. But I guess maybe a good place or next place to go is talk about when should I be considering an IDE, and I know there are some situations where I think it's more of thou shall do IDE in other cases where well maybe I want to. So, maybe let's expand upon that a little bit. When is it required? When is it nice to have, and those sorts of things?

David Pudwill: I guess if you don't mind, I'd back up a little bit and say it's helpful if you're planning on conducting a clinical study to just think again, as we've talked about in some previous podcasts, about the overall landscape and where you're trying to get to, what is your end goal. And FDA has a couple different programs that you can avail yourself around early feasibility studies, and we'll talk about that maybe a little bit later here as well in terms of what that might look like But if you're looking to do breakthrough kinds of products or if you're looking to improve the safety of existing products, FDA has a couple of different programs that you should think about around what they call EFS, that's early feasibility breakthrough, a device designation which gives you a couple of perks, and everybody wants to be breakthrough, but not everybody's breakthrough. And then, what they call the Safer Technologies Program or STeP. So, those are just to start with as you think about the overall plan to move forward in terms of development and what you're trying to achieve, check those programs out. You're probably already doing that, but check those out and see if that's applicable. And then, in terms of the actual IDE study itself, FDA has put together a bunch of really great links for you on their CDRH learn landing page, and there's just countless numbers of presentations and resources, some stuff back in 2014. There were a number of presentations and things that FDA put out that are really quite useful right. And one slide in particular in there, and FDA presents it a couple times in there, the IDE basics presentation. You can watch the video. You can also go look at the slideshow slides in a PDF format or something. And on page 12 there, there's this great little graphic, and it talks about or maps out if you've got a device study that's either exempt or not exempt. And then, what falls into that not exempt category in terms of significant risk or non-significant risk? So, first and foremost, there are a lot of clinical studies that are just exempt from IDE regulations.

Jon Speer: And maybe elaborate a little bit when you say exempt. Not assume that these terms are entirely clear to everyone. What does that mean, exempt?

David Pudwill: Yeah. So, that means you're not going to have to submit an IDE to FDA for that, and there are even some non-exempt studies where you may or may not have to submit an IDE, but under the exempt, you're going to be exempt from at least the FDA requirements around this depending on the context that you're doing some of this. You might still need to submit something to an IRB, but in terms of exempt studies, this is going to be commercial devices used according to their labeling that probably wouldn't need or I wouldn't expect you to have an IRB approval for anything like that where the device is already on the market approved for that particular type of use. A lot of diagnostic devices, because there's not a patient-safety consideration depending on how you're using it and if you're just evaluating the product against standard of care versus actually trying to inform the clinical judgment and decision making, a testing of consumer preference or a modification when determining a safety and effectiveness and not putting subjects at risk, again same kind of thing for the diagnostics. Some of these as well, there are device types that fall into some of these categories as well. You'll find certain wound care products, for instance, fall into this exempt category or they fall into, I shouldn't say exempt, they're going to be in the non-significant risk category and not require an IDE, but for exempt, you've got veterinary devices, custom devices, and a couple of other categories as well or, let's say, practice medicine. So, you may not be on label for this particular use, but if a clinician is using it under practice medicine not in a study per se, that's also going to be acceptable not require an IDE study or if it's basic physiological research and FDA goes into a little bit of detail there. So, that's the exempt category. All of those are going to not require an IDE. And then, we get into the non-exempt category, and this is where, let's say, wound care devices are going to fall in into the non-exempt, but non-significant risk for certain types of products and FDA's laid that out, and those are going to generally require IRB engagement, but not require an IDE. And even for the exempt and non-exempt, this doesn't tell you anything about whether you need an IRB engagement, but it does tell you clearly for anything that's exempt, you don't need FDA's engagement. Once you get into the non-significant risk, it's going to be a determination by an IRB about it being non-significant risk, and you definitely have an IRB involved in those sorts of non-exempt studies or generally you would because they're making that risk determination. And then, you have what are considered significant risk studies. And the initial determination on that is going to be made by the investigation sponsor, and that might be a physician. It might be a company. And that initial determination about where you fall into the risk categorization is actually made by you if you're running the study. And then, depending on what that looks like and whether you need to engage in IRB to run that, they'll then sense check that determination about, let's say, significant risk versus non-significant risk. And if they disagree, then they might ask you to submit something to FDA to confirm, and you can actually get a Q-Submission into FDA to get FDA's determination on that.

Jon Speer: Okay. And a couple reactions. So, exempt, not exempt, I guess clarification, this should not be confused with device classification. The same terms may be used for device classification, but these are not necessarily connected to that, correct?

David Pudwill: So, yeah. So, you may require a 510(k) submission for a product. So, it's not exempt from a 510(k), but it could still be exempt from, let's say, an investigational device exemption. So, yeah that's a very good clarification. Well, if you're exempt from, let's say, 510(K), probably you're going to find yourself in a category where you could get the device on the market without a clinical study. So, not to say that all 510(k) exempt devices would be exempt from IDE requirements, but you're more likely to find a path to be exempt from IDE sort of investigational device exemption requirements if you have a 510(k) exempt product. But if you require a 510(k), you're not 510(k) exempt, you still might be exempt for certain device categories from the IDE requirements.

Jon Speer: Okay. That makes sense, and I guess one follow-up on that. If I have a device that's on the market and regardless if it's class 1 510(k) exempt or 510(k) clearance, et cetera, there's a potential that I can still do an exempt type of clinical study. If I start to explore other indications for use, that might be part of that decision tree that makes it not exempt. So, there is a decision tree that one would follow if I'm understanding correctly.

David Pudwill: Yeah. And if you're looking at de novo and PMA products, I mean the likelihood is that you're not exempt, and the likelihood is that you fall into significant risk just because of the device classifications and how you'd probably be looking to study the product, but it's going to vary based on what it is that you're studying, how it is that you're looking at it. And you could lay out scenarios where even high-risk devices could fall into a non-significant risk kind of a study. And this is again where you look at certain diagnostic devices or, let's say, you were testing consumer preference of a couple different available options, and you've already got your clearances. You've got a high-risk device, but you have a potentially exempt study.

Jon Speer: Sure. And I guess that's another follow-up question I wanted to explore a little bit significant risk, non-significant risk. I believe this is still a thing. I know once upon a time, FDA had or probably has a pretty good guidance document about significant risk, non-significant risk. I assume that's still a thing to these days, right?

David Pudwill: Yeah. So, FDA has a lot of content out there on significant risk versus non-significant risk. Also a lot of detail on just within the context of submissions, and this is useful for you to think about as you're headed towards presumably if you're going to do a clinical study, you're also looking to get a device marketed, this benefit risk determination and how to think about risk in the context of the overall process to get the device onto the market.

Jon Speer: Yeah. I wanted to add that because I don't want people to be confused. Yes, you as device developer manufacturer, whatever the case may be, have some part of the decision making process as far as significant, non-significant risk, but it's not like you're just going to say" Oh my device is non-significant risk." There is guidance.

David Pudwill: There's guidance. You could say that. FDA may disagree with you. So, it's one of those is one of those situations where, yes, you do have some information that will guide your decision making around what falls into significant risk, what doesn’t. FDA's also laid out a couple examples of what's going to fall into, let's say, significant risk. So, for instance, products that are in implant or used in supporting or sustaining human life or of substantial importance in diagnosing, curing, mitigating, or treating disease, or preventing impairment of human health or otherwise poses a risk. So, this is just some broad brush swathes of what would constitute probably a significant risk kind of a device. And the IRB, in these kinds of cases, you're generally going to be engaging with an IRB, would be my expectation, or you've already conducted a clinical study, and you've already got a device on the market for that kind of a significant risk category products such that you know the gradations of what's going to require a study, and what wouldn't. And FDA is going to be the final arbiter. If there are any disputes, you don't really want to be in a position of being at odds with FDA. And FDA does have a mechanism where you can submit a Q-Sub to them. It's the kind of thing though where a lot of these should be somewhat cut and dried and sometimes even for some things that should be straightforward. And IRB will send a sponsor to FDA. I was involved in looking at some of these SR, NSR determinations. Usually, it's a medical doctor in that a subject area of expertise that's going to actually be looking at it making a different determination at FDA. And then, you've got people who were doing what I was doing maybe helping to drive some of the administrative documentation around that and getting a determination back to a study sponsor. Occasionally, you'd see some significant risk or non-significant risk questions come to FDA that were relatively straightforward. No, FDA is going to make the cut it's non-significant risk. And sometimes, you just have a very conservative IRB, but FDA will make those decisions both for a device being a significant risk or not being a significant risk based on the objective evidence that you present to them. So, the best advice I would suggest if you're going down that path is to make sure that you provide sufficient information to justify why. If you believe it's a non-significant risk study, why that is, and what your justification is, and provide as much context around that as you can because that will really help FDA then make that determination. And if you get the IRB to agree with you upfront, you can head that whole situation off because there's always a chance that FDA is going to disagree with you if you think it's non-significant risk. And FDA is going to lean in general towards a slightly more conservative judgment on gray area issues.

Jon Speer: Yeah. I mean the Q-Sub, I want folks also remember Q-Sub and pre-submission, those are synonymous with one another. If you go to FDA with a Q-Sub or pre-submission and say, " Hey, do I need an IDE clinical investigation for this?" If you ask that question, well, the crosstalk.

David Pudwill: The answer is probably.

Jon Speer: It's probably going to be yes. To David's point-

David Pudwill: Always.

Jon Speer: To David's point, do your homework. Do the due diligence ahead of time. Engage in IRB. And even after you do the due diligence, engage in IRB. Go through the SR NSR decision tree and so and so forth. There's a decent chance it still might be ambiguous. Then, that's the opportunity to come to FDA, but don't just say, " Hey, FDA, do I need an IDE," because to your point, they're probably say yes.

David Pudwill: Well, and I've seen this kind of thing as well in other areas primarily. I think for SR NRS, it's going to be a little bit more objective, but there's still some level of subjectivity here. But definitely in some other areas where FDA guidance is pretty clear, you can go to FDA and ask them the question. And usually, if you're asking them, that indicates to FDA that you believe there might be some ambiguity. And so, I know there are some situations within companies where your commercial team wants a clarity from FDA about something, and they're not trusting the regulatory team or something like that. As much as you can do to try to head that situation off, please do. Wherever possible, please trust your regulatory people to make good judgments about some of this stuff because if you push the regulatory people to ask FDA a question that should be clear-cut, FDA is going to look at it and say, " Why are they asking? There must be something here we're missing." Is there any reason we might think that we should give them the answer they're not looking for? And you just put yourself in a situation where sometimes the answer should be clear-cut, and it should be, let's say, that FDA doesn't need to be involved. But if you ask FDA whether they would like to be involved, they might tell you yes. So, just be prepared for that. Yeah. Don’t be asking questions that you know the answer to if you can clearly document that.

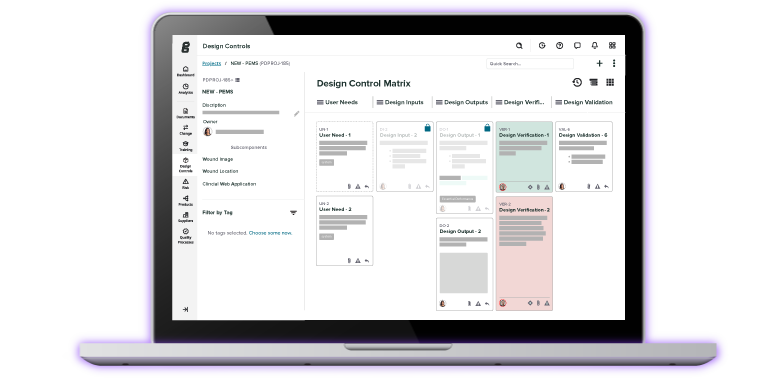

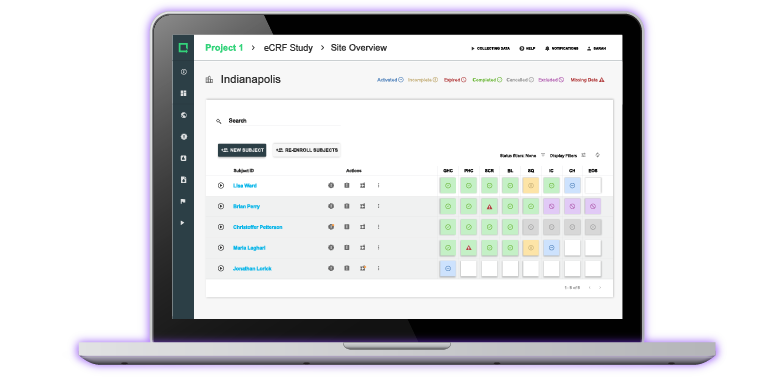

Jon Speer: For sure. Folks, I want to remind you I'm talking to the Mr. Regulatory, David Pudwill. You can learn a ton more about him and a couple of places. You can go to mrregulatory.com, M-Regulatory, all one word, no hyphens.com. As I mentioned at the beginning, you can also go to the Mr. Regulatory YouTube channel, quite a few different episodes and videos on a lot of things. Some of it's really nuanced type of topics, but it's that's stuff that you don't deal with every day, and you need somebody that has the expertise and knowledge. And certainly, Mr. Regulatory has that. Also, while I'm taking this brief pause to remind you that Greenlight Guru medical device success platform is out there, and it is helping companies all over the world bring devices to market and keep them there. We built this platform for the medical device industry. It has been designed by actual medical device professionals. So, go check it out, www.greenlight.guru. And one other exciting announcement that we just launched, we have this thing called Greenlight Guru Academy. What is this? Well, we've built out this education platform. We're going to be frequently adding some different courses and learning paths to teach you more about things like design controls and risk management and regulatory submissions and so and so forth. So, it's out there. It's available. Consume it. Enjoy it, and be on the lookout for exciting new courses coming soon in the Greenlight Guru Academy. All right.

David Pudwill: I am really happy to hear about more training opportunities and things available because it's really been one of the reasons that I started doing any of these videos to start with, is just the quality of some of the information that's out there, FDA's got some stuff. We've talked about this in this area. In particular, there's a lot of volume of information. You can go through it. I don't know that FDA has ever really condensed it well, not that we're condensing it particularly well in this conversation either. But at some point, probably try to put together some slides that better condense, okay, here's the map because FDA's information is from, let's say, 2014. And maybe, they'll get around to doing it. But I think at the moment, they're busy with a bunch of COVID issues. And speaking of which, there are some COVID considerations as well for investigational device exemptions and clinical studies. And I have a couple videos on some of those topics.

Jon Speer: We'll make sure to get those links out there, but I mean that's an interesting topic maybe in and of itself, but maybe we'll dive into a little bit now, but I know when COVID first came to be and the world shut down so to speak, there was an impact on the med device industry there for a bit, and specifically in the area of like IDEs and clinical investigations both here and abroad, what are these COVID IVD... or I'm sorry, COVID IDE. See, I'm getting all the acronyms messed up, David. But what are these programs that you alluded to?

David Pudwill: Yeah. So, FDA has put out some guidances on statistical considerations COVID specific issues that you're going to run into. You've now got some confounding factors due to having a COVID population. A lot of this was maybe a bigger impact very early on in the pandemic for ongoing studies or for people trying to start studies and figure out how to adequately control them. There are some other considerations as well in terms of remote monitoring of studies and different ways that you can actually collect data in the current environment where we're trying to limit the number of in-person interactions that people have in terms of the number of human contacts that are going to put them at slightly higher risk for maybe getting COVID simply because the number of people who are coming through their house or who are meeting with them in a clinical setting. And so, trying to reduce that impact as well. And FDA has been very sensitive to that. And it's just an ocean of information they put out around COVID and clinical studies and all this as well.

Jon Speer: Yeah, and I think that's a really good point. I mean I think this may be a prediction, but I think our world, med device world, is in some aspects probably going to be forever changed, and I think in some cases, it's for the better, like you mentioned, the remote monitoring. If you go to more the inspection and audits and things like that, I think there will be a virtual component to some of these activities. You and I are chatting over video. I remember being a kid and the idea of talking to somebody live over video, I mean that was reserved for Star Wars and Star Trek. You would have never imagined doing that in real life. So, I think there's a lot of benefit to some of those types of things, but I guess getting back to specific into the IDE realm, maybe, we'll explore a little bit. So, 510(k), do I have to have clinical data for my 510(k)? Yes or no.

David Pudwill: Maybe.

Jon Speer: Maybe. It depends. crosstalk

David Pudwill: Sorry.

Jon Speer: That's okay.

David Pudwill: It'd be nice it was clear-cut.

Jon Speer: When yes, when no?

David Pudwill: When yes, when no. It's primarily going to be linked to the risk of the product. So, for instance, for certain types of devices especially if you're going into the home, so, let's say, one area that I'm familiar with is hemodialysis. So, for those kinds of products, if you're in the clinic, FDA will accept bench testing. You might have to do human factors studies, and it's going to be a whole lot of information and testing, and you might have to be engaging nurses and patients, but not in a formal clinical study to get a product like that into the clinic. But if you're trying to put a device like that in the home, then FDA's expectation is that you run a small clinical study for other types of products as well. So, let's say, certain types of stents are going to require them for vascular stents, fairly large studies for certain types of pacing and defibrillating products. And so, one product and panel that I was involved in was for leadless pacemakers, and FDA end up putting those products on the market after gathering a whole lot of information on their safety and efficacy. So, specifically, if it's a new category of device or a significant departure from the existing technology, you're probably going to need a clinical information. Now, for some of these is going to fall into, let's say, PMA category. So, for, let's say, the electrophysiology products, that's going to be your PMA. You're more likely to need clinical for these high-risk type products. But even for hemodialysis systems, these aren't PMA products. These are 510(k) products, but they're still relatively high risk, direct access to the vascular system. And significant things can go wrong in some of these kinds of treatments. So, you have things like that, that are high risk, usually electromechanical products. You might have other kinds of high-risk 510(k)-type devices as well where just historically, we've dealt with these kinds of products under a 510(k) paradigm.

Jon Speer: All right. So, next question, all PMA devices require an IDE, true or false?

David Pudwill: False. Yeah. So, there's actually some interesting... I won't go too deep into it, but especially for products, I believe, with other PMAs on the market already as of, let's say, 2000, I might be getting the date a little off here, but FDA can actually leverage other companies' clinical data to put your device on the market. Now, some of that is going to require some strong comparator to that, let's say, predicate PMA. It's not quite the right way to frame it, but if you're making a, let's call it a generic PMA product, think about it like the drug avenues, FDA could leverage existing clinical data for devices after a certain cutoff date, and it's prescribed in some FDA guidance actually on this, they can leverage existing clinical data. So, even if you would expect clinical data to be required for that type of product, if sufficient information exists and FDA's use some language around fourth of a kind and stuff like this, then, you might not need a clinical even for a PMA-type product. It's going to be a narrower set of cases than where you need it, but-

Jon Speer: Yeah. Okay. Next, I guess, question for you, so, let me make sure I phrase the question. So, I have a 510(k) device or a device that's going to follow 510(k) path, do not need the clinical data to support my submission, but I want it for more market acceptance investors, whatever the case may be.

David Pudwill: You might need it for reimbursement.

Jon Speer: Reimbursement. So, there's other scenarios that even though it may not be required, I'm still might have to do an IDE if I haven't that cleared.

David Pudwill: Well, you might need to do a clinical study, but if you don't require the IDE, usually, you're going to need to do an IDE if you're going to leverage that clinical information for a marketing submission. So, that's really what's going to drive your need aside from, let's say, significant risk safety, patient safety considerations. If you're going to be using that data to support a marketing submission, you probably want to be collecting that under an investigational device exemption.

Jon Speer: Okay. That makes a ton of sense. So, I figured we could wrap up today and just give folks a little bit of, I guess, high level what goes into an IDE submission. It is a type of regulatory submission. And, folks, I want to direct you to 21 CFR part 812, I believe, covers all investigational bias exemption criteria. So, go check that out. But from a high level, David, what goes into an IDE submission?

David Pudwill: Yeah. It's going to be part 812.20. I just noticed I've got a typo here. The name and address of the sponsor, and this is just laid out. So, you can go search the regulations available online. I used to have a set of these books on a bookshelf behind me. I don't know what your experiences with this. They used to print a new set of them every year, but you can just go online actually and search for this. If you search that text, it should pop it up. And you can look at the detail, and it's actually linked in some of the links. I think we'll go ahead and get to people. But it lays out 12 items that need to be included, and this is the name and address of the sponsor, a report of prior investigations and the current investigational plan, a description of manufacturing, processing, packing, and storage of the device, an example of the investigator agreement and a list of people who signed it or a list of investigators who have already signed it actually in terms of the submission. Then, you need a certification that all investigators who participate in the investigation have it already or anybody who joins the study will sign it. Then, you need a list of the name, address, and chairperson of each IRB that you're engaging with, a list of the participating institutions. If you're selling a device, the amount that you're charging for it, as well as an explanation of why that doesn't constitute commercialization. That's a an important piece of information you're going to want to include there. You're also going to need either an environmental assessment or an exclusion. In my experience, usually, you can explain why you qualify for an exclusion, but there might be cases where you would have to do an assessment. You need to include the labeling, and you also need to include information that you're going to give to the subjects in the study as well as the informed consent documentation. And then, any additional information as requested by FDA. And that last bit is really going to be maybe device specific or in response to an inquiry from FDA as you go through. So, it's not something necessarily that you provide upfront to them. So, that lays out the overall landscape of what you need to give them. And then, within 30 days after you submit this, FDA is going to come back to you and give you a decision either that your study is approved, that your study is approved with conditions or that your study is disapproved, and they might include some additional elements that you don't have to respond to around study design considerations and future considerations. And a lot of this is laid out in some of what FDA has put together on their website. So, a lot of really good resources there.

Jon Speer: And this may be myth. I can't remember it right. I seem to remember that if you submit an IDE submission, and you do not hear back from FDA in 30 days, that constitutes de facto approval. Is that still a thing or was that ever a thing? Do you know? I mean I'm guessing today we're all-

David Pudwill: Technically, it is a thing.

Jon Speer: Would you advise people to do that?

David Pudwill: I wouldn't advise you. I mean technically, you would be within your legal rights to do so in certain circumstances. I mean FDA's, they sent people letters in some instances when they're getting submissions in, and there's some kind of a delay in either the government being closed or there was a massive snowstorm, and they were sending out updates to people around IDEs and things like this. I mean I would generally advise you not to just start your study. I mean technically, you could, but FDA, it goes out of their way to meet this 30-day deadline, and they're aware that if they don't just from a statutory standpoint, you could just start your study which is one of the reasons that they will give you an answer within 30 days. Expect that by midnight on day 30, you will get an answer. There are very rare circumstances where that's not the case. So, I wouldn't get an itchy trigger finger to move forward without a letter from FDA because one is coming.

Jon Speer: All right. All right. So, David, I guess to wrap up this kind of high-level conversation on IDE, it might be good to just give people a typical timeline how to flow through this, not that this is etched in stone by any stretch, but the timing of events. We've talked about Q-Subs. We've talked about the contents of IDEs. We've talked about scenarios, when and IRBs and NSRs and SRs, and that sort of thing, but maybe help people navigate this process a little bit more succinctly.

David Pudwill: Yeah. And just before I forget because I will otherwise, when we think about disapprovals, FDA is only going to be able to disapprove your study based on patient safety considerations. So, back before 2012, FDA would oftentimes disapprove studies based on study design issues or issues that they believed were going to affect your ability to commercialize the device and get a marketing submission through in the future, but a congress put a stop to that. And so, FDA is only able to disapprove you based on patient safety consideration. So, keep that in mind. And that's why I mean the current letters that FDA sends out are a lot more complicated than they used to be in terms of where crosstalk different information falls, and they give you extra information and additional sections that aren't really part of the letter and anyway. So, that's part of part of why, is that they will approve the study. Even if they have concerns with it, they'll let you know what those concerns are, but that doesn't preclude you from starting the study. It might preclude you from getting the device on the market on the backend which means for all intents and purposes-

Jon Speer: You're kind of wasting everybody's time.

David Pudwill: Even if you get an approval, if you get a bunch of study design considerations, you're probably waiting to start the study until you resolve those in most cases. But in terms of timeline, so to get back to your actual question, you're going to generally want to go in with a pre-sub or a Q-Sub as we've talked about to FDA. And just put this in front of them. Get them a picture of the device and a little bit of detail about what you're looking to study. So, if you know that you're headed down that route earlier on in the process, it usually takes about 70 days. Maybe, let's call it 60 days from when it's received by FDA for you to get a meeting on. I generally recommend that. Try to schedule a meeting with FDA. Try to have an actual teleconference with them or an in-person meeting if we get back to doing that again here in the future and just have an opportunity to talk through what it is that your plans are for development, what it is that your plans are for, let's say, a study and any protocol questions you might have because this is the opportunity that FDA is going to have to give you their input, their feedback. And you can hopefully head off any major issues or concerns that might come up.

Jon Speer: So, before we move to that next major chunk from a timeline perspective, how early is too early to do a pre-submission? I'll cram two parts into this question. And is my Q-Submission, is there a difference between a 510(k) Q-Submission and an IDE Q-Submission or can these all be blended together?

David Pudwill: You can kind of blend some of this stuff together. I would generally try to separate it out to some extent. I mean you can ask questions about the study and questions about the device or questions about your planned approach to commercializing the product within one Q-Sub. It depends on where you're at in your timeline. I generally recommend there's not really a too early time. As long as you've got some information, I generally recommend pictures. See, if you can get pictures, maybe even samples of prototypes or something in front of FDA. I mean that kind of stuff, if you're able to get that to them and as long as you're not creating some hazard because you've got sharps or some issue you're sending them needles. But if you can get something, a sample of some mechanism of the product or at least getting some diagrams and pictures and if you can try to use color, I mean just little things about, it's less about-

Jon Speer: I mean you're telling a story and crosstalk

David Pudwill: Yeah. Absolutely.

Jon Speer: Who wants to watch a boring story or listen to a boring story? Spice it up a little. I mean be factual, but tell a story that's compelling.

David Pudwill: Yeah, and some of it is trying to tell the human interest side of it, to some extent, because while FDA doesn't consider that, let's say, formally, look. I mean we're all human. And so, if you can tell a compelling story about why you're doing what you're doing, you can really get some advocates on your side within FDA to help you drive things forward, and they're going to be more inclined to spend more time and effort getting you good advice and good information. And they're going to be doing that in any case, but it's going to help you, I think, if you can tell a compelling story. So, definitely, yeah. That storytelling aspect is a big piece of this pre-sub, Q-Sub interaction. And I would also suggest as I have it before, that you find an image or you find a diagram or something that is going to remain consistent as best you can imagine into the future that you can reproduce every time you put something in front of FDA because it's something for them to latch onto because they see so many of these submissions that if you can give them a point of reference-

Jon Speer: crosstalk almost like the brand so to speak, right?

David Pudwill: Yup. Exactly. And then, all of a sudden, it's like, "Oh, I remember this product," and it'll help smooth things along if there are people who've already been involved in previous interactions especially because for some of these, you might have a pre-submission interaction with FDA years before you actually start the IDE study. I mean hopefully, you can move things along faster than that, but knowing how this sometimes goes, the various reasons you get derailed or anyway.

Jon Speer: crosstalk, pivot, whatever the case may be. I mean I think that's not quite a given necessarily, but it's probably more common than not, that time between your pre-sub and time between your actual IDE is going to be a while. Even for me, something I did yesterday, I have to sometimes go to my calendar and like, "What did I do?"

David Pudwill: Did I take notes on this meeting?

Jon Speer: Yeah. crosstalk All right. So, pre-sub and then, time passes. And then, what happens?

David Pudwill: So then, you get to your actual original IDE submission, and you might even get to a point where you do a follow-on pre-submission. So, it depends on maybe what's happened. Usually, you want to interact with FDA and figure out what you're doing in your pre-clinical work because there's certain bench data and maybe animal testing you're going to need before you go into human subjects. And FDA can help you work that sort of plan out. And based on what happens, usually, it doesn't go quite to plan in my experience. I mean maybe there's some people out there that they planned it out, and it went exactly as they thought it would. Go ahead. Just submit the IDE, but potentially, do a follow-on Q-Submission interaction just ahead of doing an IDE. Make sure you build it into your plan maybe a couple of months ahead of doing the formal IDE submission just to iron out any additional questions you might have now that you've got all your data. You're working on assembling the package, but you have a little bit of time where you can get some information to FDA before you have everything really ready in terms of protocol. You're lining up your study sites. You're doing a lot of this work in the background. Do an interaction with FDA. And then, get this formal original IDE study submitted. And that's going to need all these pieces that we talked about. That's going to need your investigational protocol, some details on the device description as part of that. You're going to need details on your manufacturing, and you're going to need the information that you're going to be presenting to your study subjects and your informed consent and anticipate as FDA goes through like, I don't know, usually dozens if not hundreds of pages, usually hundreds of pages in a submission like this. They're probably going to come back with changes. So, be careful about going to the presses with a bunch of, let's say, physical printed documents and things if you can hold back. You can do some stuff printing at risk, but just anticipate you might have to reprint sections of this after FDA reviews it and ask you to change a bunch of stuff.

Jon Speer: Yeah, and those scenarios, I mean especially those early stages. I highly recommend the print-on demand type of situation. It doesn't have to be a nice trifold glossy thing. I mean it can be eight a half by 11, and this type of scenario. It's more about the content, but there will be changes to that. I mean I almost would guarantee that.

David Pudwill: It's almost a certainty that something will change, but, yeah. And within 30 days of that, then expect. So, the timing of your submission matters. So, I would generally recommend avoid Thanksgiving. Avoid Christmas. I don't know. If you know the government is shutting down, just see if you can avoid some of these kinds of things because the longer FDA has to review your submission, the more likely you are to have some interactive back and forth and successfully get to an approval without FDA putting basically your study on hold with a disapproval letter or an approval with conditions that has conditions that you basically mean you're not starting the study. So, the timing of the submission matters. It shouldn't. I appreciate that, but just practically, it does because if FDA will get you an answer within 30 days but if they have less time, that means they're going to more likely have questions that make it to you in their formal letter than if they've got a little bit more time. Maybe, they can have a couple more interactive back and forths, resolve some issues even if the letter you get is smaller. I mean I see that as a win in many cases just to reduce the number of questions.

Jon Speer: And I think another thing, hopefully, this is obvious, but if you're going to submit information to FDA, that's not the time for you now to go on vacation for a couple of weeks and be unavailable.

David Pudwill: You need to be available. Well, you might be able to submit it and go on vacation for a week. I would try to do it the second week. Submit it. Make sure it actually makes it in. Then, take off for a week, but then, be back for those last two weeks. And even then, your point is well taken. It's like definitely in those last two weeks and probably the full 30 days, FDA might be reaching out to you for stuff. And if you can quickly turn it around and get something to them in a timely way, you're going to improve the odds that you get your submission through as an approved IDE.

Jon Speer: Sure. All right. So, what are the couple of steps that come to mind as far as the IDE?

David Pudwill: Yeah. So, the next piece here is you're going to get a formal letter from FDA, and it usually is going to be sent by email. You're going to get to your submission correspondent, get details on what FDA's concerns are, if they have them or that you're approved or approved with conditions. Probably, there are items that FDA is going to want you to address in most cases. You're almost never going to get a clean approval. Now, you might get a clean approval with future considerations, things for you to think about. Maybe, they've flagged that you need some additional testing end points for your actual marketing submission, but usually, you're then going to be in a position maybe 50% of the time, and I haven't actually looked at the 2020 numbers. FDA publishes numbers on how many submissions they approve just outright, how many get them approval with conditions and how many are disapproved and sort of the number of iterations and how that overall landscape looks for all of their IDEs. But in a number of cases, you're going to have an amendment. So, you're disapproved, let's say, 25% of the time when you get disapproved, something in that ballpark. It might be higher, might be lower depending on the device type. But in some of the cases, FDA is going to disapprove the study. You're going to have to come back with an amendment additional information to address FDA's concerns. If you get an approval, that follow-up is going to be a supplement potentially to address their concerns. And this is probably happening in parallel where you're enrolling your sites. You're identifying your investigators doing all this work. Some of that, you can be doing before you get the approval. It's just whatever you already have assembled on that, you would submit to FDA. But you don't actually have to have any sites enrolled when you submit your study to FDA. It would be, but oftentimes, you will. So, you could submit it without any sites enrolled. You could submit it with some, but not all of your sites enrolled, and you'll be following up with additional information in the future. So, that whole bit around enrollment of sites and at least getting them ready even though you can't initiate the investigation yet, getting all that lined up and ready can be going on in parallel. crosstalk the biggest time frames that you're going to run into are actually issues around the IRB schedules and getting on there, I think, about it as a docket for review. But that's going to be one of the biggest challenges that you're going to have this, is less actually your interactions with FDA from talking with a lot of people running clinical studies, your bigger hurdles actually with the IRBs and getting through that piece of it. crosstalk

Jon Speer: Can I add a couple of things there?

David Pudwill: Yeah, please.

Jon Speer: Yeah. My experience even the lead up to all of this, it seems like you have sites that are engaged. It sounds like or you get this impression and this feeling that enrollment is going to be a breeze once you get going. That's rarely the case. So, enrollment is probably going to go slower than you think and the site engagement and getting them on boarded and active is probably going to be a little bit more challenging than you think too even if they are experienced with doing these sorts of things.

David Pudwill: Yeah. And the more you can get lined up... I mean some of it is, you don't want to enroll, let's say, sites too far ahead of enrolling patients because, then, maybe they lose interest and all this, but if you can get some of that lined up and then, you can be doing your submission to FDA and then, in most cases, you're going to get an approval fairly early on in that whole process. But you're going to want to build in a buffer of time where you can address study design considerations, these kinds of things and then, tweak any of the documentation you need to engage with the sites on and update your procedures and processes and maybe your exclusion criteria for subjects, and these kinds of things if FDA has some comments around all that. You have a lot of work in, let's say, getting to initiating the study at that point, and some of that engagement with FDA is probably happening simultaneously.

Jon Speer: Sure.

David Pudwill: And then, you get to a point where six months after your approval, you then have to start submitting reports to FDA about your investigator list. Now, you can get a waiver from FDA for certain details in terms of notifying them when you add a site, but then, you have to let them know once you've enrolled all of your sites. So, there's certain things that you can build into your submission to reduce some of the burden and reporting on the back end, but it's going to be tedious. Just expect running an IDE study is going to be tedious and a lot of paperwork, and you really want to have somebody involved in that who knows.

Jon Speer: Yeah. I think that's an important thing about this is, it's not like you get the permission to do so and then it's like, " See you later." I mean there's still culpability or responsibility to have that back and forth dialogue or communication with FDA. So, I think that's really key. I think a lot of times, people forget about that.

David Pudwill: Yeah. If you change the device, if you change your protocol, you're going to need to submit a supplement. You're also going to need to provide reports on annual progress. So, every 12 months, you're going to need to give FDA an update. You're also going to need to identify any unanticipated adverse events in a report to FDA depending on how serious that is. You've got different reporting expectations around the timelines for this. And then, you're going to be providing investigator lists. And eventually, you're going to get to the stage where you're done with the study, and you're going to submit a final report. But I would caution you be careful about closing out your IDE study too early. Usually, it depends. Sometimes, you might close your IDE study and then do your marketing submission. Oftentimes, you might want to keep the investigational device exemption study open and continue your follow-up while your marketing submission goes into FDA because, sometimes, they might come back and say, " We really want five more subjects," crosstalk or something like this.

Jon Speer: That's a really good point. I remember scenarios. And then, if you close that, now you got to go back.

David Pudwill: You got to go back to the drawing board. It's a lot easier if you've got the study still open, still active. You haven't yet submitted your final report. I've seen situations when I was at FDA where we would review the information from the IDE in the marketing submission before we actually reviewed the final report. And then, the final report close-out was basically just a formality because we'd already reviewed all the information as part of the marketing submission. You go either way, and there might be some device groups at FDA that want to see it one way or the other, or they might take issue with that, but it does, especially if there's any possibility that FDA is going to want you to go collect more clinical data or they're not happy with a number of subjects. It's a lot easier to modify an existing approved study than to open a new one even though practically, it should be a comparable level of effort. You've already got the documentation. But just logistically, it's a lot more complicated.

Jon Speer: For sure. All right. Anything else that's important about the IDE timeline and process?

David Pudwill: I think that mostly covers it. I mean the regulations suggest that within three months after termination of your study that you need to be submitting that final IDE report. So, think about that in terms of how you're structuring your study and how you're thinking about definitions of what termination or completion of the investigation actually looks like where maybe see if you can get yourself some flexibility on that termination completion. And then, you can put a delay, let's say, the closure and final IDE report to FDA and the IRBS. That mostly covers that, I think, in terms of timelines and content. It's a lot of information. crosstalk You could spend days probably reading documents and watching videos, and that's assuming that you know what you're looking at. crosstalk

Jon Speer: So true. And I liked your point earlier when I was mentioning Greenlight Academy, and I'll talk to you after the episode. Maybe, we can figure out a couple of different learning paths that we can put out there. Maybe, we can explore that because I think to your point, there is a large quantity and volume of information, but just figuring out which parts and pieces of that and how to navigate that. You and I know what we're looking for when we go to what the FDA website. If you're a lay person-

David Pudwill: Good luck.

Jon Speer: Good luck. Yeah. Call Mr. Regulatory. Go to mrregulatory.com. David Pudwill, thank you so much for being the guest and talking about IDE today. We'll have you back to talk about something else regulatory related here real soon. So, thank you so much, and-

David Pudwill: Thank you. It's been a real pleasure.

Jon Speer: Yeah. Absolutely. And folks, again mrregulatory.com. M-Rregulatory.com. Go to YouTube. Watch the videos, Mr. Regulatory, amazing stuff, really helpful to learn more about de novos and PMAs and IDEs and all those sorts of things and more. Check it out and again, Greenlight Guru, we're here to help you with your medical device quality needs helping you through design controls risk, managing your documents and records, and all those quality events that happen such as complaints and campus. Go to www.greenlight.guru to learn more about the Greenlight Guru medical device success platform. I love to have a conversation, understand your needs and requirements, and see if there might be an opportunity to help you. As always, thank you so much for listening to and now watching the Global Medical Device Podcast. This is your host and founder and Greenlight Guru, Jon Speer, and you have been listening to the Global Medical Device Podcast.

ABOUT THE GLOBAL MEDICAL DEVICE PODCAST:

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Nick Tippmann is an experienced marketing professional lauded by colleagues, peers, and medical device professionals alike for his strategic contributions to Greenlight Guru from the time of the company’s inception. Previous to Greenlight Guru, he co-founded and led a media and event production company that was later...