Understanding the Connection Between Complaints, CAPAs, and MDRs

.png?width=4800&name=podcast_standard%20(2).png)

Today we are going to talk about the connection between complaints, CAPAs, and MDRs. They are all interrelated and they have a big part of developing your company’s culture and affecting your risk management processes.

Mike Drues, president of Vascular Sciences and expert on all regulatory matters when it comes to medical device development and production, will be our guest today. Mike is a regular guest on the show, and our listeners know that he really knows his stuff. Be sure to take the time to listen to the show.

Listen Now:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some highlights of this episode include:

- The connection between Medical Device Reports (MDRs) and complaints: Does one lead to the other? Sometimes it’s a two-way street.

- Whether the current criteria for necessitating a CAPA should be investigated and maybe changed.

- Why reframing the negative thought process behind getting a complaint into thinking about it as an opportunity can keep companies thriving and patients safer.

- The importance of having a criteria for when an MDR or complaint should give rise to a CAPA.

- How frequent reviews of a product line can help you track the root causes of various issues and see the forest through the trees.

- Thoughts on risk management and the importance of having a sound risk management process can mitigate, but not eliminate, risk.

Related Resources:

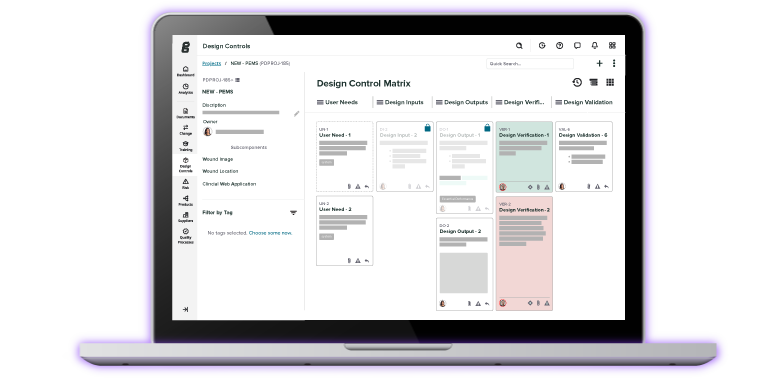

Greenlight Guru Risk Management Software

Memorable quotes by Mike Drues:

“Some companies don’t have a specific way to evaluate which MDRs necessitate a CAPA investigation.”

“We have to remember that it’s all well and good to read in mission statements that they care about people... but let’s put our money where our mouth is.”

“We can manage risk and mitigate risk, but we can never eliminate it.”

Transcription:

Announcer: Welcome to the Global Medical Device podcast where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Jon Speer: Welcome to the Global Medical Device podcast. This is Jon Speer. Let me tell you a little bit about this upcoming episode on the Global Medical Device podcast. My guest is Mike Drues. You know him, you've listened to his podcasts with me before. Great information always comes from these conversations that I have with Mike. This one is no exception. We talk about the connection between complaints and CAPAs and MDRs. And we also start to tie in risk management and how all of these things are interrelated and how they become very important to the foundation of your company's culture, as well as to your quality management system. So enjoy this episode of the Global Medical Device podcast.

Jon Speer: Hello and welcome to the Global Medical Device podcast, this is your host, the founder and VP of Quality and Regulatory at greenlight.guru, Jon Speer. I have my friend, frequent guest on the Global Medical Device podcast, Mike Drues from Vascular Science, Vascular Sciences, excuse me. Welcome, Mike, to the podcast this morning.

Mike Drues: Well, thank you, Jon. Always a pleasure to be with you and your audience today.

Jon Speer: Well, Mike, you and I have... And we've talked about a lot of things in this world of the medical device industry. Things like design control, verification, validation, intended use and so on. We've also talked a little bit about CAPA and complaints and MDRs and risk management and all those sorts of things. So what I thought we could do today is talk a little bit about some topics like complaints and MDRs and CAPAs and then try to figure out how and where and if and when to tie those things into this thing called risk management.

Mike Drues: I think that's a great topic, Jon. And to start it off, why don't we dig into the relationship between MDRs, medical device reports, which we talked about recently, and complaints. And I'll start it off and then I'll let you to chime in. The question is, "Does one lead to the other?" In other words, as you, and I'm sure your audience know, most of the time, a complaint comes in from the field from a customer that's using one of our medical devices and that might lead to a report based on it. I think that's the common scenario, but that street does run in two directions occasionally. And I don't know what your experience has been on this, Jon, but occasionally, an MDR will be filed independent of a complaint.

Mike Drues: And I think the most interesting scenario that I've seen when that happens is when a company continues to test a medical device after it's in use, after it's on the market. As you probably know, most companies don't usually do this, but I think some companies, certainly the more prudent ones do, and if they find a problem, then they might report that prophylactically. What's been your experience, Jon, in general, is there a relationship between MDRs and complaints and does one necessarily lead or follow the other?

Jon Speer: Yeah, that's a great question. And I'd say my experience has been mostly... Well, on all these topics, CAPA, complaint, MDR, all these sorts of things, my experiences have been that people are very reactive, so I haven't seen too many people go out and seek [chuckle] opportunities to identify MDR. And I'm not suggesting that you do, but the way I've seen this happen is that, as you'd suggest, the complaint usually comes from the field. Somebody using your product in some way, shape or form, and they identify an issue and the company usually finds out after the fact that while this MDR has happened, this potential adverse event has occurred. And so then they triage that and they go down the MDR path. But then they also log that into their CAPA system. And I don't know, and is that the right way? I don't know. Maybe, seems like we're always so reactionary on these things. What do you think, Mike?

Mike Drues: Well, I think, I don't know that there's necessarily a right or wrong. I do think when it comes to CAPA, one of the things that gets a lot of companies in trouble is they don't have a very specific or objective way to evaluate which complaints or which MDRs necessitate a CAPA investigation. And one of the things that I always encourage companies to do and I'm sure you do this as well, Jon, I'm sure it's one of your best practices, is companies need to have a criteria to evaluate these complaints or MDRs or what have you, to better determine under what situations that a CAPA is initiated and under what it's not. And I also take it a step further, and by the way, this is not as far as I know, Jon, and you can correct me if I'm wrong, this is not required as part of the quality system, but maybe it should. That CAPA criteria system, if you will, those parameters that will help the company decide when a CAPA is initiated, that should be revisited from time to time. In other words, just like a risk file, it's not supposed to be, at least in my opinion, a static document.

Mike Drues: It needs to be revisited periodically and updated or revised. The question is, how frequently should it be revisited? The regulation doesn't say that either. I personally don't think the regulation should say that. I think that should be up to us as manufacturers. The short answer is it depends. It depends on how well established the technology is. In other words, if your technology is very well established, if your device and similar devices have been around for a very long time, and we have a long history of it, and it's pretty well understood, then maybe you do not need to do that very often. Maybe once a quarter, maybe once or twice a year might even suffice. On the other hand, if it's a very new technology without a track record of success, especially if it's a high risk device, maybe a class three of a life sustaining or a life supporting device, then I think we have to be much more aggressive in revisiting those things. Maybe once a quarter is not a month, maybe we need to do it... Sorry, not enough, maybe we need to do it once a week. That's up to the situation. Jon, what do you think about having criteria and should they be revisited?

Jon Speer: I totally think that there are areas, lots of areas of improvement in the space. I mean, year after year after year, FDA shares the inspectional observation data from when they go to med device companies, and look at the quality systems and documentation records and so on, and companies year after year after year are cited for issues with CAPA, and issues with complaints, and issues with MDR, these are topics that almost always are at the top of the pile as far as what FDA has identified as major issues during inspections and from the ISO world, those who go down the 13485 path. I know corrective action, preventive action, that's a big deal there as well. And now it's ISO 13485 2016, it's starting to bring in this MDR type of approach as well, so it's aligning even more strongly with FDA, so it doesn't use the term MDR per se, this talks about regulatory reporting, and complaint management, and so on. So companies do struggle with this and I think they struggle with this because they've been kind of status quo.

Jon Speer: They've... Again, I'm gonna mention it probably a few more times today and you'll probably hear me in future conversations and podcasts and so on, talk about this, we all react to a situation that we wait for something to happen. And a lot of the metrics that we put in place to monitor complaints and CAPAs and so on, they're also very often times, lagging indicators, meaning they're kind of after the fact. So I think that we, Mike, you and I... You recently shared at an event that I was in attendance that you're out to change the world one person at a time, and I'm with you.

Mike Drues: Well, thank you Jon. I've can... I can use all the help that I can get so thank you. But seriously...

Jon Speer: So, I guess... Go ahead.

Mike Drues: Go ahead. No, I was just gonna share an example of this, a very, very timely example that I'm involved with right now, and unfortunately, I'm gonna have to keep this incredibly vague for obvious reasons, but I'm involved with a very high profile product liability lawsuit. And one of the things that the medical device manufacturer is being accused of is not notifying the folks here in the United States of a problem. When in fact they knew about the problem and they didn't notify the EU about the problem. And so I would like to think that regardless of what the regulatory or quality or ISO regulations say, that companies would do the right thing. I mean, to me, this is common sense. If you have a problem, I think that we... Never mind regulatory obligations, I think we have an ethical obligation to notify people as to what is happening. After all, I joke about this, I say this is as a poker game between the company and the FDA and I mean that, but on the other hand, this is high stakes bingo and we are talking about people's lives here, and I do think we have to remember, it's all well and good to read in the mission statements of companies, that we care about people and blah, blah, blah. Well, those words are easy to say.

Mike Drues: But let's put our money where our mouth is. So... Anyway, it's a challenge, but at the end of the day, we are talking about people's lives and we have to at least try to do the right thing.

Jon Speer: Yeah, I think so many of us in the industry, and I'm generalizing here, of course, but I think so many of us when we hear these terms, CAPA and MDR, and complaint, the knee jerk response is cringe, we're like, "Oh no, I can't have those things. Those are bad things. We can't have a CAPA, that's a bad thing, we can't have a complaint, it's a bad thing." So, what if we flipped it around and looked at it from a different perspective? What if we looked at, "Well, it's unfortunate, sure, of course, we're designing and developing and manufacturing medical devices that we want to help people. And when something adverse happens, of course, that's something that is an unfortunate event". But what if we took these things that we've learned, even if it is being a little bit reactionary, but what if we took these things that we learned and we used these as opportunities and we said, "Aha, there's something that we can improve about our product and use this as a learning opportunity"?

Mike Drues: Well, Jon, I don't know, you're a very savvy guy, I'm sure you realize what you just did. But for the benefit of those in the audience that don't, what you're describing, what you're applying is one of the most fundamental tenants of the design controls, and that is the concept of feedback. Your outputs become your inputs, which by the way is not unique to design controls. This is basic biology. The concept of feedback from endocrinology or neurology has been happening since the beginning of life on Earth. So I think that's a great example, almost a poetic example of how we should apply not the regulation, not the letter of the law, but the philosophy, what its intention is in order to try to help us continue to improve. Once again in the quality world I hear people use phrases like continuous improvement and so on. Well, we need to take the the complaints and the MDRs and so on. And yes, you're exactly right. It is very unfortunate when something bad happens, especially when it negatively affects the outcome of a patient. There's no question about it. But let's at least learn from that to try to prevent it from happening again. And as we've talked about in one of our previous discussions, specifically on CAPA, I think both of us agree that we've gotten very good at the CA part of that equation, but not necessarily the PA. And that's very unfortunate, I think we can do better than that.

Jon Speer: Right. Yeah, I agree, and I know we're for those that are staying with us, Mike and I are certainly talking a little bit more on the philosophical realm of, maybe the way the universe should be [chuckle], but maybe we can bring it down to a little bit more pragmatism. Obviously, companies are at a point where they'll either, they've got a quality system in place, and they're trying to triage or figure out how and what to do, what should be captured as a complaint, when do I need to do an MDR, how does this feed into my CAPA system? So maybe we can bring it back into a little bit more of a tactical way for the next few minutes, and kinda start to talk about or figure out is there a magic bullet or a magic answer, so to speak, as to, a determination as to when a complaint or an MDR, when do I need to make that part of my CAPA system? Do do you have any thoughts on that?

Mike Drues: Well, I do Jon, and I agree 100%. Let's bring this back down to reality. It's nice to wax philosophically, from time to time, but after all, we all have jobs to do. So, maybe as an example, we can drill in a little further, I would love to hear your thoughts, Jon, on the suggestion that I posed a few minutes ago, and that is having a criteria that will help us determine when a complaint or an MDR or any sort of an incident should give rise to a CAPA. I think it's very difficult to speak in broad terms, remember the Medical Device universe is a very broad universe. We have on one end of the spectrum, Band-Aids and EKG monitor, s all the way to the other end of the spectrum, things like implantable artificial hearts. So it's very difficult, probably impossible, to set up a generic criteria. Once again, this is why I say that this should not be in the regulation, it's just impossible to write regulation that's that broad. But I do think that each company needs to have a set of criteria and you can generate this by just having your R&D and regulatory and manufacturing folks sit in a room one afternoon and do a sort of a brainstorming session, as to what the criteria should be, and if you already have a product on the market and you do have a few complaints, or perhaps even a few MDRs, you might wanna look through those and see which ones led to a CAPA and so on.

Mike Drues: So you build a set of parameters and then as I said earlier, you on some regular basis, once a week, once a month, once a quarter, once a year, what have you, you go back and you revisit those to update and revise to make sure that you're not missing anything. And then one other pragmatic suggestion, and this is going well beyond what's required in the... Even in the newest ISO standards, as I know Jon, and if I'm wrong, please, please correct me. But probably on a yearly basis, what we should do is sit down and go through all of our complaints and MDRs and so on, and look to see if there's anything that we've missed. In other words, one of the challenges when you're doing your job on a day to day basis is you don't necessarily see the forest through the trees.

Mike Drues: And one of the things that I find kind of interesting is a lot of companies, and this is not a criticism, but an observation, a lot of companies will miss seeing similarities where no similarities seem to exist. In other words, you might have a series of complaints or even CAPAs that you're looking at independently and when you look at them independent one at a time, you don't necessarily see that, "Gee, maybe there's an overall pattern", and engineers like to use the phrase... Root cause. Well maybe there's an underlying root cause or a root root cause, if you will, that's leading to all of this. So those are some of the suggestions that I have, Jon, I'm sure you have many more, but what do you think of those or what would you like to add?

Jon Speer: Well, maybe just a slightly different perspective on that because as you were talking, the gears started turning in my head and as you were sharing those tidbits I was thinking, this is a bit of a twist on product program management, if you will, looking at it through a different lens of course, but it's really about being holistic and looking at the entire product line, but maybe also from a program standpoint within the company, and they have multiple product lines, looking at all of your product line, and let me give a little bit more details about what I mean there. So if you look at, and as Mike suggests, maybe do some sort of monthly or quarterly or some sort of frequent review of a product line, you can look at the issues of this product over time over history and you can use this as a means that track and trend different sorts of issues and then it's good to monitor these things, and see something that is off your trendline, or unexpected. It starts to happen, especially if you have some means to do so as an early indicator or early warning system, this might give you an opportunity to be somewhat more predictive or preventive, in actions that you take.

Jon Speer: For example, you may identify that there are... And we haven't... We didn't talk about non-conformance but that might be a nice lead in a way to be predictive, but if you start to identify certain sort of issues happening over and over and over again, it may point out that, "Hey, maybe there is a design flaw here that we weren't aware of. We thought things were good, but now that more people are starting to use this it's... There's this one feature that continually causes some sort of issue, and maybe that needs to go back and we need to do some as you suggested, a moment ago, some more work on the design control front, maybe we need to revise our product in some way, or maybe it highlights that there's something happening on our manufacturing line that we need to be aware of." So it's really about using this data to your benefit, but that's product line focus. But what if you aggregated this data, this information, across all of your product lines? You may find, as you say, that there's a common root cause across multiple different product lines and it might highlight or identify some additional opportunities to improve that.

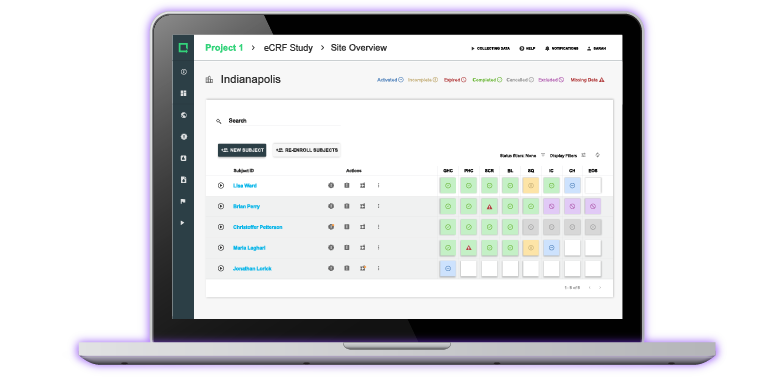

Mike Drues: Well, once again Jon, you raise an excellent point. Especially for people working in relatively large companies that might have many different products or in some cases different versions of the same product. It's sort of a riff, I think, on what I mentioned a moment ago, of, again, trying to see the forest through the trees. And to be honest with you, Jon, we... And through all of our discussions we've purposely tried to stay away from making commercial endorsements for specific products or anything, but one of the things that I got to point out to your audience here is, when it comes to automating processes like this, tools like your Greenlight product does a wonderful job of stuff like that, because it will, from the most basic level, and I know obviously your software can do much more than this, but simply putting in reminders, of, "Hey, it's that time of the month or it's that time of the quarter. Have you revisited your CAPA criteria, have you had your annual CAPA review meeting?" That kind of thing. So obviously your program can do much, much more than that, but...

Jon Speer: Sure.

Mike Drues: But that's a starting point. And once again for larger companies that have multiple products, you might have separate engineers that are working on different products and it can be difficult enough for the same person to see the forest through the trees sometimes. But when you now are talking about trying to see the forest through the trees, through different sets of eyeballs. Now it becomes even more challenging. So maybe Jon, we should move on... I'm sorry, go ahead.

Jon Speer: No, I was just gonna add that even more than just looking at your product, that there's also some rationale for maybe going beyond your four walls and seeing what other competitors are doing and a lot of this information is in the public domain. So, in fact even in some cases for technical files for Europe and things of that nature, especially if you start to do clinical evaluations and things of that nature, there's an expectation that you know what the state of the art is for this type of product in the industry. So, that may even suggest that you do your homework and see what other competitor products and what issues they're having and make sure that your product addresses those shortcomings of this other product.

Mike Drues: I think that's an excellent point as well. And you have a broader perspective on this than I do, so I'd be curious as to hearing your experiences. But I love the idea of incorporating into your quality system, into your CAPA requirements for example, not just what's happening with your own products, but keeping an eye on your competition if you're working in an area where there are a lot of similar products. So let's be honest, in the medical device industry we have tons and tons of "me toos", we call them, 510(k) so if you have products, I'm sorry, if your competitors have products out there that are having problems, should we be looking at those on a regular basis to try to evaluate are those problems that could happen to us? And if so, should we be prophylactic and should we try to prevent them from happening before they do? On the regulatory side, as you know in the PMA world for high risk medical devices that is a PMA requirement, it is not a regulatory requirement for low and moderate risk devices, it's not a 510(k) or a Denovo requirement, perhaps it should be, but it is a PMA requirement. I would love to see as we think about this, we talk about this. Maybe that added to the appropriate section of the quality system regulation, or ISO or something, I actually think that that's a pretty good idea. What do you think of that, Jon?

Jon Speer: Well, Mike, for those sharp listeners paying attention to our conversation today and we have a lot of sharp listeners, I can assure you. They've picked up that you and I have been dancing or talking about risk management the whole time, and I think that that would be a nice way to maybe try to put a big wrapper on this conversation today, so to speak, and you and I have talked about, you shared your bucket approach to risk management, and a lot of the things that you and I are talking about today certainly fit into the Mike Drues bucket of which... By the way, do you have a trademark on Mike Drues Bucket Approach to risk management?

Mike Drues: It's not a registered trademark yet, Jon. Maybe I need to file something with the patent and trademark office pretty soon on that.

Jon Speer: But let's bring it home and put the risk management umbrella, or wrapper if you will, on this conversation because like I said, we've been really talking about risk the whole time.

Mike Drues: We have. So that's a great question, and by the way for the benefit of your audience, I do have a webinar coming up that I'll be doing, hosted by your company. Thank you so much for the opportunity to do that on my... Jon calls it my bucket approach, and maybe we can put a link from this podcast to that. So the audience... People that are interested can take it here. But one thing I thought I would start to remind people when we talk about risk and linking it to what we've been talking about today is, please notice that we're talking about risk management, we are not talking about risk elimination and there's a big difference. One thing that I learned as an engineer and I'm sure you know this, Jon, is that no product is perfect, and all products, regardless of how diligent and careful we are, all products are gonna have problems from time to time. Sometimes we can anticipate them, sometimes we cannot. And so the point is that we can never completely eliminate risk. After all, when you get out of bed in the morning, there's a chance that you might cross the street and get hit by a bus, does that mean that you don't get out of bed?

Mike Drues: So obviously, certain risks we can try to mitigate assuming that we know about them, but there are other risks that we don't know about. And this is why I think all of the stuff that we've been talking about, not just today, but I think in all of our discussions, in general, we have to take a more holistic approach, we have to try to think, how does risk relate to complaints, relate to CAPAS, relate to recalls, relate to design controls and quality system. It's kinda coming from a medical background myself. I often use the body as a metaphor. There's no tissue in the body that's totally independent of everything else. All of the tissues in your bodies are in constant communication with everything else, and that's what quality and regulations should be. We shouldn't be focusing just on CAPA, just on complaints, just on MDRs, what have you.

Mike Drues: We have to look for the relationships between the two. So we can manage risk, we can, in many ways, mitigate risk, but we can never eliminate it. And what it really comes down to is one of the most fundamental questions of all of regulatory science, and that is what is safety? How safe is safe? And for the engineers in the audience, how much testing is enough? These are not simple questions, but we have to think about those from time to time and whether we're coming to the FDA in terms of a product submission or whether we're manufacturing a product, and we're talking about consistency, or reliability, or something like that. Fundamentally, I think all of these issues are the same. It all comes down to... It all comes back around to risk.

Jon Speer: Right. It most certainly does, and I think so many people, I think that you're right, I think they set out to think, "Hey we can eliminate risk from the equation". But that's... Folks, that's just not your objective. That's why having a sound solid risk management process is important, and Mike and I've talked a little bit in this podcast about being able to, from time to time, assess and evaluate what's happening. And risk is really, that lens or a lens that you can use to look at the situation. You can use the risk management lens so to speak, to try to anticipate what you think might happen based on experiences, both ahead of time, but then once that product goes live and is in use, then being able to use this information that you're learning from your complaints that happen. And folks, complaints are gonna happen, accept that this is the reality. It's okay, I promise you, it's okay. It's what you do with the complaint that becomes important. Don't try to make a device that's gonna be complaint free. Complaint is like risk, you're not gonna eliminate it from the equation, but usually we see...

Mike Drues: We can't eliminate it, we have to deal with it, we have to have a process to deal with it.

Jon Speer: We have to deal with it, exactly. Exactly.

Mike Drues: And we have to update that process from time to time. And that I think is the most important. And the last thing that I wanted to share and then I think we need to wrap this up, Jon, is it's becoming more and more my experience, and Jon, you might agree or disagree as I talk to more and more people in this industry. I've been playing this game now for about 25 years. Unfortunately, they are approaching the whole area of regulation or quality or risk management, or what have you, as really nothing more than a series of tick box on a form, a checkbox on a form.

Jon Speer: Yup.

Mike Drues: And maybe you or some others might disagree. I think that's quite frankly, very dangerous. That's not the intent of this whole process, just to simply tick off these boxes. There's an adage that we use in medicine, frequently, and that is, "The surgery went perfectly, but the patient died anyway." Well, the medical device engineering equivalent of that is that we designed the Medical Device perfectly, but the patient died anyway. The regulatory equivalent of that, is we followed the regulation perfectly, we did all that FDA or Health Canada or whoever asked us to do, and yet, the patient died anyway. Unfortunately, these things happen more frequently than some people might like to admit. And I'll give you one quick example, I mentioned the tools that are available for risk management now, like the Greenlight tool. It's a wonderful tool, but like any tool, while the safety and efficacy of that comes down to the skill level of the user, and I had a conversation with somebody just recently a few weeks ago who was looking to automate many of their processes, including the risk management, and they were trying to make a decision as to which tools to go with, because obviously there are several to choose from.

Mike Drues: And I started to ask them, so what I thought were some pretty basic questions about risk, and quite frankly, they had a difficult time answering them. And I said "Look, you're welcome to use whatever tool you want, I'm happy to give you some recommendations, but this is not necessarily gonna solve your problem, you need some help on what that tool is going to be doing for you". It's kinda like a scalpel. If I put a scalpel in the hands of a skilled surgeon, they can get wonderful results. If you take the same scalpel and put them and put it in my hands, probably not so good results. [chuckle]

Jon Speer: Yeah, I'm not gonna let you operate on me, so don't worry Mike.

Mike Drues: Exactly, exactly. So perhaps one of the takeaways from our discussion today is, yes, ticking off the boxes on the form are important, so that when you have an auditor come in, you can show them, "Yes, we did this. Yes, we did that." But it's not just simply a series of check box on a form, it's gotta be more than that.

Jon Speer: Yeah, it's... Just hearing that reminds me of some conversations that we've been having at Greenlight and some of the people that we've been talking to, and it's really... Gets down to what is the company's culture or attitude when it comes to quality and regulatory. And I think that's very important. If your mentality is that I'm gonna check a box and throw it over the wall and send this down the line, so to speak, and you kinda have the wrong attitude when it comes... You definitely have the wrong attitude when it comes to quality and regulatory. Mike, you said another thing a few moments ago that I jotted down that, about a tissue, when you look at it from a body perspective, there's no tissue that can be independent of another, I'm paraphrasing, of course, but if you think about your company or your mentality or your approach to quality and regulatory as a body, so to speak, all of these things are connected and you cannot separate one from the other. You have to be able to show and demonstrate and live and believe that all of these things that you're doing, complaint management, CAPA management, MDRs, risk management, design controls and so on and so on, and so forth, that all of these things are intended to make your body better.

Jon Speer: And I think Mike, let's leave that as the the final word today. As you mentioned you've got a webinar that we're doing with you or you're doing for us rather here soon, and it's on the topic of the risk management. Yes, we will absolutely share that with everyone listening. And Mike, as always, it's been a real pleasure to chat with you today.

Mike Drues: Well thank you, Jon, and the very last thing to just remind your audience is, and I've said this before, but I think it wraps up our comments today. When a company gets a 510(k) clearance, when they get a PMA approval, when they get a CE mark, when they get ISO blah, blah, blah, certified, that is the academic equivalent of being a C student. That does not mean that you're doing a good job. That simply means that you're passing. And I think as an industry we can do more.

Jon Speer: Yeah.

Mike Drues: We need to set the bar higher. Thank you Jon, as always, for the opportunity to be part of your discussions and I look forward to speaking again in the future.

Jon Speer: Alright, thank you, Mike Drues from Vascular Sciences. Ladies and gentlemen, if you want to make your QMS system, your body healthy and whole again, reach out to the folks at greenlight.guru. We'd be happy to talk to you about how you can do that. And all you have to do is go to greenlight.guru and request more information and reach out and we'll happily have a conversation with you to see if there's an opportunity that we can help you address those situations. Again, this is Jon Speer, your host, the founder and VP of Quality and Regulatory at Greenlight Guru and you have been listening to the Global Medical Device podcast.

About The Global Medical Device Podcast:

![medical_device_podcast]()

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Greenlight Guru is the leading cloud-based platform purpose-built for MedTech companies. The end-to-end solution streamlines product development, quality management, and clinical data management by integrating cross-functional teams, processes, and data throughout the entire product lifecycle. Greenlight Guru’s...