Tips for Avoiding Problems with the First-In-Human Study Process

.png?width=4800&name=podcast_standard%20(2).png)

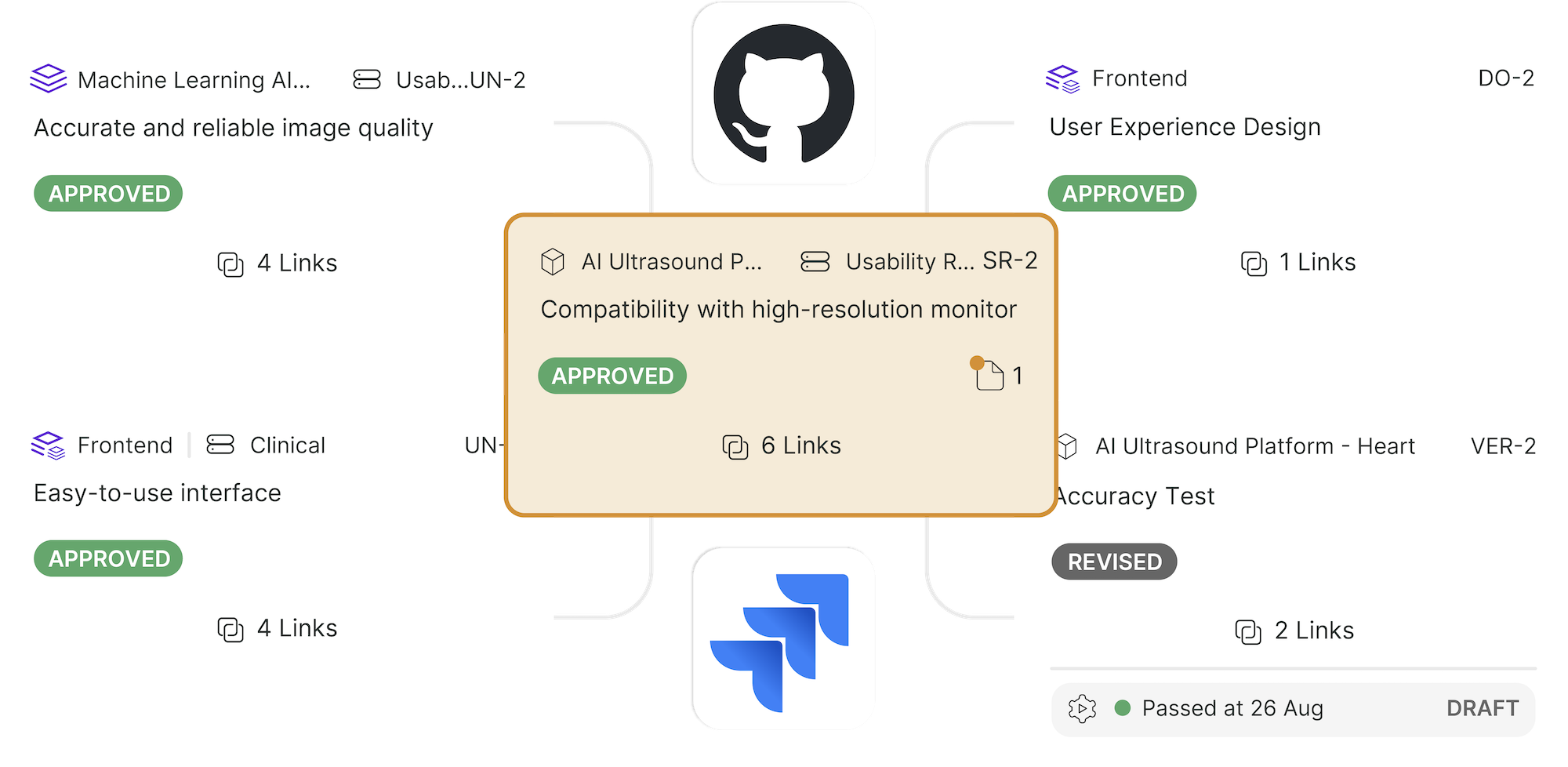

When it comes to moving from the conceptual phase of developing a medical device and actually doing first in-human studies, you first need to prove that your device is safe and effective.

The documentation that goes along with that can be cumbersome, but, as Michael Drues, today’s guest, says, it’s necessary to prove that what you’re doing is safe.

Today we’re discussing the topic of first in-human studies and what needs to go into the development process before devices can be used on and in actual people.

Mike Drues is the president of Vascular Sciences. He consults with FDA, Health Canada and other regulatory bodies and also works with medical device companies to help them get their products ready for approval. He has the unique perspective of seeing medical device issues from both sides, because he works with regulatory agencies as well as development companies.

Listen Now:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some highlights of this episode include:

- Some of the logistics that go along with those in the proof-of-concept phase: how to meet regulatory and ethical obligations without constructing too many barriers.

- The importance of objective evidence that a new device is safe, and how to balance that with the potential burden of documentation.

- How to handle offshore trials if you want to submit the data later as part of your FDA regulatory data submission.

- Hints on how to choose a country as a place to perform your offshore trials.

- Tips on avoiding problems with the first-in-human study process.

- How to handle the pre-submission process?

Links and Resources:

Information Sheet on FDA Acceptance of Foreign Clinical Studies

What's with the Rush to First-In-Human Studies?

Memorable quotes by Mike Drues:

“Working with different agencies gives me an uncommon perspective. I can see issues from both sides.”

“The number of devices that are requiring human data is rapidly increasing.”

“Greater than 95% of devices have never been tested in a clinical trial.”

Transcription:

Announcer: Welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable, insider knowledge, direct from some of the worlds leading medical device experts and companies.

Jon Speer: Hello. This is Jon Speer the Founder and VP of Quality and Regulatory at Greenlight.guru and you've tuned in to the Global Medical Device podcast. On today's episode, the topic is first-in-human. What are you doing to prepare for those first-in-human studies? Are you going here in the US for those studies? Overseas? Do you have your design controls and risk management where they need to be? What about your quality system? A lot of things to address, as you approach first-in-human. With me on this episode is Mike Drues of Vascular Sciences. So sit back, relax, and enjoy this episode of The Global Medical Device podcast.

Jon Speer: Hello, this is Jon Speer, the founder and VP of Quality and Regulatory at Greenlight.guru and welcome to another episode of The Global Medical Device podcast. Today, I've got my good buddy Mike Drues. Mike is the president of Vascular Sciences. Mike consults with FDA, he consults with Health Canada, he consults with other regulatory bodies. Oh, yeah, and he consults with medical device companies whose job is... Mission in life is to help get medical products to market as quickly as possible, cutting through all that red tape in the meantime. Mike, welcome to the podcast.

Mike Drues: Well, thank you, Jon. Always a pleasure to be with you and your audience.

Jon Speer: And, Mike, I know we catch you on the road today. It seems like you're traveling from coast to coast, all over the globe. You've got an exciting life, [chuckle] doing all kinds of things. What is it like really to work with FDA on one day and then the next day to be working with a med device company? I can imagine that's really interesting.

Mike Drues: Well, to tell you the truth, Jon, travel challenges aside, I really love it because it really gives me... Working both for companies as well as the FDA and other regulatory agencies, it really gives me, I don't wanna say a unique perspective, but certainly an uncommon perspective because I truly am able to see a lot of these issues from both sides. And I really use that, try to use that, to my advantage when I work with companies to try to get them to look at things from the FDA's perspective. And similarly when I work with the FDA or Health Canada or HSA in Singapore, or whoever, to try to get them to look at it from the company's perspective. So simply put, I love what I do and I try to use it to my advantage.

Jon Speer: Alright, well that's great to hear. Mike, in line with the work that you do, in line with the work that I do, a common theme or milestone that companies are often in pursuit of is this first-in-man or first-in-human study, developing a technology to a point where you can get it to a stage where it can be used clinically to try to gather data or demonstrate that a concept works. So I imagine that you have people asking you, "Hey, Mike, how quickly can I get this device to be used in human clinical studies?" I'm sure that question comes up often.

Mike Drues: It does frequently, Jon. And just like in the drug world, we wanna try to get our devices into actual people as soon as we possibly can, because after all what good is it to anybody to pursue a design for a medical device, spend lots of time and money on it only to come to find that when we do get it into people, it doesn't work for whatever reason and therefore we've wasted a bunch of time and money. So I think most people appreciate the value, the utility, the importance of getting it in to people as early as possible.

Mike Drues: What it really comes down to is the logistics, the question that I get, and I'm gonna throw this back to you, Jon, is if we're going to... If we're still, for example, in the proof of concept phase and I happen to be in California right now, I just had this conversation with the company that I'm working with out here. If we're still in the proof of concept phase, in other words, we think this device might work, and probably will work but we don't know for sure, not to any degree of certainty. We wanna get it into a person. And do we need to be making these initial devices according to CGMPs? Do we need to have a quality system in place? Do we have to have designed controls? So maybe Jon you wanna give some advice or an example on how we can meet our regulatory obligations and more importantly, our ethical obligations, but at the same time, not constructing so many barriers in terms of time and money that it just doesn't make it feasible to a company, especially a small company to do this.

Jon Speer: Sure, now, that's a great, great question and one that it comes up often, if you're gonna... My opinion is this, if you're gonna go to take your device regardless of its super early proof of concepts or if it's late... Later stage, there's a couple of questions that you definitely need to answer, and one of those questions is around safety. How do you know that that product is safe for actual human use? And there's all kinds of different technologies, whether it be electrical device or a catheter type product or patient contacting type of product. There are things that the medical device product developer is morally and ethically obligated to do, and ensuring that that product that they're going to be using on humans is safe.

Jon Speer: Now, I realize there's levels to this, but keep in mind that the whole premise behind design controls is about demonstrating that your product is safe. There's also a component of effective, and of course, human clinical use is one means to be able to demonstrate some effectiveness of that product as well, but safe is definitely the key word. And I'm a big proponent of design controls, and even if you're going to go very early stage with a proof of concept product, I'm a big proponent of let's capture design control criteria. Now, you may not have the final device design controls that you're dealing with. It may be, again, this early version, but there's still things like user needs and design inputs, and outputs, and verification activities that you can do to capture, document, and ensure that that product is safe. Mike, do you have different thoughts on that?

Mike Drues: Actually, Jon, my thoughts are exactly in alignment with yours. I think, and we've talked about this topic before. I think the most important thing, whether we're filling out all the forms, whether we're dotting our I's and crossing our T's, perhaps I shouldn't say this in a podcast recording, but I don't really care. That's not the important part. The important part is, as you just alluded to, we're doing the things that we should be doing, that we need to be doing, that makes sense from an engineering and a biology perspective. Issues like you mentioned safety, that's a very nebulous term. So let's get a slightly bit more specific in terms of biocompatibility, in terms of sterility, in terms of electrical safety, the list is endless.

Mike Drues: So even in the early proof of concept phase, I think it's very important that we are doing those kinds of things. And one other thing that I've noticed is that oftentimes, people use the phrase, "clinical trial", almost in a generic or nebulous sense, but to me, there are lots of different, shall we say, types of clinical trials. In other words, for very early proof of concept work, I might not have any intention whatsoever of collecting formal data and presenting it to the FDA or anybody else. I might simply have say 10 different iterations on the same medical device design. It's not feasible for me to pursue all 10 of them, I need to narrow that down to perhaps two or three. And all I want to find out is, which two or three of these 10 are worth pursuing.

Mike Drues: In that particular case, it's not gonna be nearly as complicated. We're talking about doing something really quick, really simple, really easy, ideally fast and cheap as well. Now, that said, that's not an excuse for not doing all of those things that you just alluded to a moment ago, but it doesn't have to be as nearly as overwhelming as it can be. I think a lot of people get very turned off to clinical trials because they just think it's gonna be a lot of time, it's gonna be a lot of money, it's gonna be a lot of paperwork. And oftentimes that's the case, but it does not have to be that way.

Jon Speer: Yeah, I'm right there with you. I think sometimes when people hear a term like "design control" or "risk management", that automatically their antenna go up and they're thinking, "Whoa, this is overly burdensome, heavy on documentation," and so on. And you said something a moment ago that I want to dive into just a bit further. You said you don't care if the person fills out all the forms, or makes it nice and pretty, but... I agree with you. You got to have the proof, you gotta have... You got to be able to point to some sort of objective evidence, some sort of report or criteria or evidence in some way that says, "Yeah, that's safe." That biocompatibility is a good one, right? If I'm gonna use my product that's going to be contacting a person, I should have substantial evidence to support that, hey, we addressed that body contact and duration for this type of product. And I need to have, whether it be data reports or some sort of evidence, that I can use. Again, it's about being able to show and demonstrate that safety, so I think that's really key.

Mike Drues: Once again, Jon, you and I are singing exactly the same [chuckle] song there. And just to be clear, I don't wanna give people the impression that filling out the forms is not important, that's not my message here. But I have seen situations more than I would like to admit, to be honest, where companies have filled out the forms, so to speak, correctly, all of their paperwork is in order, and from a design control or a quality management system perspective, they're doing everything that they're required to do. But the content, quite frankly, is crap. And there's sort of an expression sometimes people use, it's like putting lipstick on a pig. I just don't want to get, to lose track of what's most important.

Jon Speer: Yeah, I'm with you. I'm with you right there. The thing about that people, I think, get, lose the concept, at least again from my perspective on design controls, is design controls, it's oftentimes shown as a linear or a waterfall process, like a progression. But my way of looking at design controls, it's iterative. Especially, let's use this idea of I'm going to take this proof of concept version to human clinical use. Well, I'm gonna go through a pretty quick pass of user needs, and inputs and outputs, and verification activities, and then I'm gonna use the information that I gather from this first-in-human study, and I'm gonna feed it back in. And I may go back and revisit my user needs and inputs and outputs and verification again, so it's iterative and the whole intent here is that every time I do something, I wanna learn something, and I wanna add value to the overall safety and efficacy of my product.

Mike Drues: Once again, Jon, you and I are in complete agreement there. And I think what we're both saying in different words but the message is the same, and that is obviously the regulation is important, and following the regulations is something that we need to do. But let's not lose track of the big picture here, and what is really important at the end of the day. So, Jon, why don't we come back to the original question of clinical data. And we've talked a little bit about doing early stage proof of principle kind of human testing. What about when we get into the process a little bit further along, and we already have a working prototype, maybe we already have a design freeze. And now we're working on a medical device where human data is actually required for regulatory clearance or approval. And by the way, as your audience probably knows, even in the 510K world, the number of devices that are requiring human data now is rapidly increasing. In the past it's been very small.

Mike Drues: As a matter of fact, here's a statistic for your audience. Greater than 95% of medical devices that we have on the market today here in the United States, greater than 95% of them have never been tested in a clinical trial, at least not for regulatory reasons. But assuming that we're in that universe of devices that do require clinical data, another challenge, and we see this in the drug world frequently as well, is more and more companies are wanting to do this kinds of work overseas outside the US, in Europe, or perhaps in some other country. Any thoughts of what people should be looking out for, or thinking about there?

Jon Speer: Well, I wanna... I'll also throw in that twist. Obviously the regulatory piece is important from a clinical perspective. A lot of the companies that you and I interact with, they're also backed by investors. And investors, a tuned-in investor or a significant milestone to raise additional capital, is often tied to first-in-human type studies too. So, sometimes that's what's driving a lot of that interest in these studies. And obviously you mentioned the outside of US, that's an area that a lot of startups, I think, are exploring these days, and probably well-established companies as well.

Jon Speer: But going outside the US, because sometimes the regulatory constraints are a little less, well just say stringent, than maybe doing a clinical study in the United States. And I think that comes with additional challenges. I know you probably have a lot to say about that as you work with FDA, as you work with Health Canada and other regulatory bodies, I can imagine that that's a really, really difficult topic to address sometimes, because if I'm gonna go outside the US and do a study outside the US, I wanna be able to use that data for any sort of FDA type submissions downstream. So, what do I need to do, do you have any suggestions?

Mike Drues: Yes, I do Jon, I have several. So, first of all as you alluded to, the primary motivation for companies for doing off-shoring of human studies, is primarily the lower regulatory burden, as well as oftentimes lower costs, and quicker... Shorter time frames, and so on. That said, if you plan on using this data as part of a US submission, or EU submission, or one of the other submissions from the major parts of the world, you definitely have to keep that in mind.

Mike Drues: Now the most important piece of advice, 'cause I see companies making this mistake all the time, is historically... Let's just talk about here in the United States, historically, FDA has not been keen on taking data from outside the US as part of a US submission. And the primary reason for that, and like you I've been playing this game now for a long time, so I've seen a bit of an evolution in thinking here.

Mike Drues: The primary reason for that is that there are some countries, for example, in the EU, where physicians are notorious for not following protocols. And anybody that knows anything about statistics, knows that when you start to try to pool your data from investigator to investigator and site to site, if not everybody is doing things the same way, it's like doing an apples to oranges comparison, and you really can't do that. So, the most important thing is that we show that all of our investigators are doing the same thing, following the protocol. And I don't mean just on paper, but actually in the clinic, or wherever your device is being used.

Mike Drues: Now, the most common way to do that is by using what's called a clinical monitor, where basically they will observe the procedure, and they will document or attest to the fact that, yes, this physician did this a certain way. So, as long as we can do that, it really doesn't matter where on the globe that we do this trial.

Mike Drues: As a matter of fact, I think the whole notion as we've been operating in this industry for a very long time of doing clinical trials, essentially the same trial in different parts of the world just to satisfy different regulatory authorities, I think that's ridiculous, it just doesn't make any sense. So, as long as we can show that everybody is doing it the same way, there isn't a problem. More recently, I think, just within the last six months or maybe a year, FDA put out a guidance specifically on using data from outside the US as part of a US submission. If anybody's interested, send me an email, I'll be happy to send you a copy of that guidance or you can certainly get it on FDA's website.

Mike Drues: But there's nothing in there, in my opinion, that's new. This is just stuff that some of us have been doing for a very long time. So, in the last example, I'll give real quick, is, I know now, at least, two, perhaps there are more, but at least two medical devices, these were PMA devices, that have gotten US approvals based 100% on OUS data. In other words, there was no US data as part of that FDA submission. Now, that's still the exception, rather than the rule, at least for right now, but I see that as a trend for the future.

Mike Drues: In other places in the world, for example, in Japan, I can't see that any... Ever happening. I can't see Japan ever approving a device for the Japanese market based on outside of Japan data. But here in the US, and another... Most other places, as long as you keep in mind those couple of things that I said, I think you'll be okay.

Jon Speer: Well, and the Japan example is a good one. I know of, at least one product, several years ago, that was introduced in the Japanese market. I don't know all of the logistics that led it there, but let's just say that there was a technology involved in the product that had an adverse reaction to people of Asian descent, and it created a big issue in Japan, and patients were having reactions, allergic reactions to the technology. And I'm sure there are other reasons for why, but I think that's the key point. And Japan is oftentimes an extreme case, but the point that I wanna touch on a little bit, is it doesn't matter, and perhaps matters less, is probably a better way to say it, where in the world you gather that data, but it's important that that human clinical data, it represents the actual intended user, and it represents the actual patient population.

Jon Speer: So I can imagine in clinical statistics and demographics, and inclusion-exclusion criteria, and end points, those are all things that are very, very important as well. But now, I think I can just say, "Alright, Mike. We got some prototypes. We did our biocompatibility, we did some sterilization testing. It's good to go. We're gonna... Where do you wanna go tomorrow, Mike? We're gonna go hop on a plane, and just go there, and sign up a few people, and use our product in a clinical setting." Obviously, there's still good science that need to be involved.

Mike Drues: Right. So, now, what we're getting into is what parts of the world do we want to go and do this? That's a topic of a whole different discussion.

Mike Drues: It's under the general umbrella of what I call international regulatory strategy. But basically my quick advice is, I look for places in the world to go that satisfy two criteria. The first is, they have a decent level of medical technology, and the second is they have little or no regulation. Now, if you apply those two criteria, decent medical technology and little or no regulation, my two favorite places to go are Mexico and India. That doesn't necessarily mean that people in Mexico or India are of inherently less worth than anybody else. That's not what I'm trying to imply here. But based on those criteria, those are my favorite.

Mike Drues: Now more recently, I try to stay away from India because there's just been too many situations in the clinical trial world, especially for drugs, where people have... Let me just say got caught doing things that they're not supposed to be doing, and so on. And so, I don't wanna suffer from the guilt by association factor. So, my favorite at the moment is Mexico. And in addition, it's got the logistical advantage that it's, at least, in the same hemisphere. So, you could go, for example, to Sub-Saharan Africa, like Togo or something like that, where they have no regulation but they also don't have any medical technology either. So, those are my thinking on that. Do you agree, Jon?

Jon Speer: Yeah. I think it's... There are parts of the world that I've heard of... Some of the companies that I work with, going to parts of Eastern Europe is pretty common, and there are other parts of Asia as well. So, I think, it's... The technology piece is important. Obviously, especially, if you have a device that requires it be plugged in, you want somewhat a place where the electricity is stable and things of that nature.

Mike Drues: Of course.

Jon Speer: The other twist that I've heard recently, Mike, is about some of these earlier stage startups, they're tying in more of a social cause to what they're doing. And they're developing a technology, or a product, or a med device that may be needed, but it's like they're almost developing it for a part of the world where there is no technology. So, I guess, that's a twist that can come into play. Like I've heard of Sub-Saharan Africa being a target for first-in-human studies, for that exact reason. So, there are twists and turns that you get into.

Jon Speer: And again, I think it's important that as you develop your technology, as you go for these first-in-human studies, your point earlier, there's no reason why I should have to repeat clinical study, after clinical study, after clinical study, in various markets. If I'm being strategic about this, I can do it one time, and be able to address multiple different regulatory markets.

Jon Speer: So, Mike, I know we've talked about quite a bit on this topic of first-in-human, and we probably, throughout our conversation this morning, have touched on a lot of issues and problems to try to prevent and avoid at all cost, but any other tips that we wanna provide to our audience today, things to look out for so that you can avoid problems later?

Mike Drues: Well, the one last thing that I'll mention and I see a lot of small and startup companies doing this, they tend to be attracted to non-significant risk or NSR devices, in part because they think they can avoid having to deal with the FDA. Because as your audience probably knows, if you have an NSR device, and by the way, that determination is best to the company, not to the FDA. So, if you determine that your device is NSR, technically, according to their regulatory textbook, you do not have to go to the FDA in advance, an IDE is not required. You do still have to get the IRB to give you their blessing, so to speak, but not the FDA.

Mike Drues: I have seen it happen a number of times where companies do that and then when they do take the data to the FDA as part of their 510k submission for example, FDA says, "What the heck is going on? We don't agree that this is NSR." And therefore, now we have all kinds of problems. So, even in the situations where a device is believed to be NSR, I take that to the FDA prophylactically in advance as a matter of professional courtesy. I go in there and I say, "Look, I'm not asking you anything. I'm simply letting you know as a matter of professional courtesy, here's our device, here's the way it works, here's our labeling, here's the testing that we've done. Based on all of these reasons, this device is not significant risk. We are not required to be here, we are not asking you for your permission to begin the clinical trial, we're gonna be doing that starting next month, but we do wanna make you aware of what we're doing and we wanna do it together, and so on and so on." It's another example of my mantra which I've shared before, and that is, "Tell, don't ask. Lead, don't follow."

Jon Speer: Right.

Mike Drues: So, it's just I've found in playing this game now for nearly two and a half decades, that the vast majority of problems that companies run into, not only are they preventable, but they're predictable. And I see lots of people making the same mistakes over and over. And so, again, as we've talked about before, don't treat the FDA as your... As the enemy, but treat them as your partner. And I think like the old adage says, "You'll reap what you sow."

Jon Speer: Right. So, on that "tell, don't ask," can you talked about communicating to the FDA that this is what you're doing, and you said doing so prophylactically, what is the vehicle and mechanism or the type of... How would I... How would you communicate that? Would you do that in a pre-submission? Would it be a documented thing? Would you pick up the phone and call? And if so, who do you communicate that information to at the FDA?

Mike Drues: Well, that's a great question, Jon. And it truly is the topic of a different discussion, maybe we'll do another podcast on this.

Jon Speer: Sure.

Mike Drues: But simply put, the most common way that this is done today is through a pre-submission or a pre-sub process. My strong advice is to do this the old fashion way. In other words, in a physical meeting as opposed to just sending in some pieces of paper. But I would definitely bring that up as part of a pre-sub. I probably would not make that the sole goal of the pre-sub. I would put that within two or three objectives of the pre-sub, but that's where I would bring it up.

Jon Speer: Alright, well that's great advice. And any other parting words that we wanna share with our audience today on the topic of first-in-human and whether or not to do it outside the US versus the US, non-significant risk versus significant risk? Anything else that we wanna share with the audience today, Mike?

Mike Drues: Well, just one other because again, I've seen a lot of companies, including some of the largest medical device companies on earth, make some of the most basic, the most amateur mistakes that quite frankly, they should never make. So, just one last thing I'll mention that comes back to what I said earlier about international regulatory strategy, I see it happen very often where a company will do a clinical trial in one place to satisfy the regulatory criteria for that particular country, and then they move on to country number two, only to come to find that country number two wants a piece of information that country number one didn't want, and now they have to do a clinical trial over again to collect that additional information.

Mike Drues: In my opinion, that's a totally amateur mistake that should never happen. It's very time-consuming, it's very expensive, it's very inefficient. So the way you prevent that from happening is very simple. You come up with your international regulatory strategy. That is, you identify the first three or four or five countries in the world that you wanna do business in. Please don't say you wanna do business everywhere right away 'cause that's probably not gonna happen. But the first two or three or four or five, you pool their regulatory requirements, and that is, you find out what all of those first countries are gonna want and then you design your clinical trial in order to capture all of that information.

Mike Drues: And I take that a step further, not just the regulatory information, but what information are you going to need in those countries for reimbursement as well? And you put that into your clinical trial design. So bottom line, yes, clinical trials are time-consuming and expensive, no question about it. But because we make so many mistakes and because we don't take so many of these things into account, let's put it this way. We can be doing this a heck of a lot more efficiently than most people do it today. And that's... I spend a lot of my time as I know you do as well, working with companies to try to prevent them from making these kinds of amateur mistakes that I see happen, unfortunately, all too often.

Jon Speer: Yeah. Absolutely. And I guess from my perspective, the key thing is always about making sure that what we're doing... And I'll steal a line that you've offered in previous podcasts, that all that you're doing during this process of bringing medical devices to market is really about following prudent engineering practices. And we talked about earlier in this session about the importance of safety and ensuring that products that I'm bringing to that the human, to be used on humans are safe. And ultimately the goal, the objective of following things like design controls, and risk management throughout the design and development process are just that, they're about demonstrating that your product is safe and effective for the intended uses.

Jon Speer: And that's one of the things that we've done at Greenlight.guru is we've developed a software platform to help companies, whether you're very early on or you've been doing this for decades, it doesn't matter. We've streamlined the process. We've given you workflows to help capture and manage those design controls and risk management as well as keeping track of your documents and records and your quality system in a Part 11 aligned environment. That just makes life so much easier, especially as you want to be aggressive with your timelines.

Jon Speer: So I wanna thank my guest, Mike Drues from Vascular Sciences today. As always, Mike, it's been a pleasure. And I want everyone to know, if you want to learn more about what you can do, what you should do, maybe what you shouldn't do, feel free to get a hold of Mike. You can find him at LinkedIn is probably the best way. Just type in and search for Mike Drues, D-R-U-E-S. His company is Vascular Sciences. Also, if you are interested in learning more about the GreenLight.guru software platform and how it can be used as a vehicle to help you capture and document your objective evidence as you're preparing for that first-in-human study, go to GreenLight.guru, request a demo, get a hold of our team, and we'd be happy to share more about that.

Jon Speer: Once again, it's been Jon Speer, the Founder and VP of Quality and Regulatory at Greenlight.guru. And you have been listening to the Global Medical Device Podcast.

About The Global Medical Device Podcast:

![medical_device_podcast]()

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Nick Tippmann is an experienced marketing professional lauded by colleagues, peers, and medical device professionals alike for his strategic contributions to Greenlight Guru from the time of the company’s inception. Previous to Greenlight Guru, he co-founded and led a media and event production company that was later...