The Bleeding Edge: Lessons Learned for the Medical Device Industry

.png?width=4800&name=podcast_standard%20(2).png)

Sometimes, do things make you go, “Hhhmmmm…” Jon Speer recently watched a documentary about the medical device industry that made him do just that.

Much of the information presented was factual, but it seemed liked the whole story was not being told. On today’s episode, Mike Drues, president of Vascular Sciences, joins Jon to explore different perspectives to give you a clear and complete picture of the industry.

The documentary focused on a few medical devices that caused harm to people, but neglected to say anything about medical devices that help people every day.

However, it elevated types of topics that start conversations and is a step to identifying opportunities for improvement. The solution is more communication, not less.

LISTEN NOW:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some highlights of this episode include:

- Those with products in the documentary declined to comment. Medical device professionals should be obligated to tell their side of the story.

- The documentary put a clinical face on the problem; not talking just about engineering, regulations, and biology - but about people’s lives.

- 510(k) vs. Premarket Approval (PMA): Documentary described getting medical devices to market may be too easy and should require more clinical data.

- Whether following a 510(k) or PMA path, it does not mean that a medical device is safer than the other. FDA’s system is not perfect; bar needs to be set higher.

- Some permanent implant devices in the documentary were cleared by 510(k). Is that sufficient? May depend on a case by case basis of regulation vs. innovation.

- A medical device can get to market without having clinical data. So, clinical data may not be necessary or more is being expected pre- or post-market.

- Systemic breakdowns of quality management software (QMS) and numerous adverse events may require thorough processes, investigation, and reporting.

- FDA doesn’t have jurisdiction over practice of medicine and physicians, but over devices used by them. Do we need regulations to make devices safer?

LINKS:

Medical Device Reporting (MDR)

Mike Drues of Vascular Sciences

Memorable qUOTES from this episode:

“They neglected to say anything about...all of the really great medical devices out there that are helping people every single day.” - Mike Drues

“Elevating these types of topics will start some conversations...a step to identifying where there might be opportunities for improvement.” - Jon Speer

“As a medical device professional...my mission...is to improve the quality of life and to leave no stone unturned in that quest.” - Jon Speer

“I think the solution to most problems is more communication, not less.” - Mike Drues

Transcription:

Announcer: Welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast, where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Jon Speer: Sometimes I come across things that make me, "hmm". And I watched a documentary recently that did just that. And the documentary was about the medical device industry. And, well, the stories and a lot of the information presented in this documentary are factual. It felt to me as though the whole story wasn't being told. And that's what I wanted to chat a little bit with Mike Drues from Vascular Sciences on this episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast, where he and I explore a few different perspectives to help give you a clearer picture of the total story.

Hello and welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast. This is your host, the founder and V.P. of Quality and Regulatory at Greenlight Guru, Jon Speer. And Mike Drues from Vascular Sciences is joining me today.

Mike Drues: Thank you Jon. Always a pleasure to speak to you and your audience.

Jon Speer: Well Mike, I know you and I pay attention to what's happening in our world and the medical device industry specifically, and try to keep our finger on the pulse of, well I guess, new, and exciting, and interesting things. Recently there was a documentary that came out that featured the medical device industry, and I know you and I both had a chance to watch that. And I thought we would take a few minutes to talk about that, because my opinion after watching that documentary, I think it only showed one side of the story.

Mike Drues: Well I think you're exactly right Jon. I think it was a factual accounting, but I definitely think it was one side. Unfortunately, the makers of the documentary, and this is not necessarily a criticism but merely an observation, they focused on a few medical devices that happen to be permanent implants that did happen to cause harm to people. In some cases lots of people. But what they neglected to say anything about, was all of the really great medical devices out there that are helping people every single day. So to use a metaphor from Fox News, I think it's important to have a fair and balanced view of our industry.

Jon Speer: Yeah, I totally agree. And the stories that were in that documentary, and I do applaud the makers of the documentary, cause I think elevating these types of topics will start some conversations. And conversations that, like, you and I are going to have today, I think are a step to identifying where there might be opportunities for improvement. I think it might be a way for us to highlight some areas where there might be some systemic breakdowns, and pose some interesting questions about 'do we need change.'

And I don't know that we're gonna get into all of that today, but I thought we would dive into some of that. I mean first and foremost it's very clear that some of the products that were featured, there have been some very significant events, and my heart goes out to those patients, and those families of those patients who have had to suffer through these adverse events. As a medical device professional for over 20 years now, I assure you that my mission as a person, as somebody that works in this industry, is to improve the quality of life and to leave no stone unturned in that quest to make sure that I bring to market is as safe and effective as possible.

Mike Drues: Well, once again Jon, you and I are singing exactly the same song. I could not agree more. Call me naïve, but I think the solution to most problems is more communication, not less. And we need more people, not just within our industry but in society at large, being aware of these things, and we need these discussions. And regrettably, I would have to put some of the blame of the one sided approach to this particular documentary on ourselves. On our industry, because according to the video both the FDA, as well as all of the manufacturer's that had devices portrayed in this video, they were all invited to participate, and according to the video they all declined to be interviewed on camera.

And call me naïve Jon, but again, how does that make the world a better place. We just simply have a one sided accounting. I think we as industry professionals have an obligation to get out there and at least tell our side of the story, so to speak, to try to provide as I said, a fair and balanced approach. And one of the things that the video did do a good job, in my opinion, is putting a clinical face on the program. This is a technique that I often use when I go to the FDA myself before talking about our particular device, the engineering, the regulations, the biology ... I will often put a picture of a patient on the screen and I will see meet Mary Smith. Before using our device, Mary Smith was not able to do x, y, and z. Now as a result of using our device she is able to do x, y, and z.

Some people accuse me of tugging on the emotional purse strings perhaps, and I can see that point, but what I'm also doing is reminding all of us that we're not just talking about engineering, or biology, or regulation here. We're talking about people's lives. And so, simply put as you said, we have to remember not just the patients, but the families, the kids. We in this industry have a big responsibility, and remember if we don't do our jobs, remember the faces of those people that you're affecting.

Jon Speer: For sure. For sure. And again folks, I want to emphasize that one of Mike's comments at the beginning of this podcast. Of course this documentary did a pretty decent job of highlighting some products that are out there that have had some problems. But if you're new to the medical device industry, or you're curious about 'is this the norm." I assure you with a 100% certainty, no this is not the norm. There are thousands and thousands, and thousands of medical device products that are out there that are changing humanity in a good way. And both Mike and myself have had the pleasure of working with many companies who are really changing quality of life in a good way. So I do want to emphasize that.

But Mike, as we talk today, there's kind of a few areas that I wanna explore a little bit. The documentary talked a little bit about 510(k), PMA, postulating that getting medical devices to market might be too easy. Kind of in line with that there was claim, or some idea thrown out there that medical devices need more clinical data before going to market, I thought we would dive into that in just a little bit. I also want to explore a couple of things that seemed to me that in these cases that were highlighted there were systemic breakdowns of a companies quality system, specifically in areas of complaints, MDRs, possibly CAPAs. I thought we would explore that a little bit. And then I thought we would wrap up today by exploring the question 'do we need more regulation to make things better.' I think I know your answer but we'll chat about that here in a moment. So does that sound okay as, I guess, a rough agenda for our conversation.

Mike Drues: I think that's terrific Jon. I look forward to being part of this discussion. [crosstalk 00:07:51]

Jon Speer: Okay. Alright. The first thing. 510(k) vs PMA, I mean some of the devices that were featured, I think all the primary devices featured were all implants, well three of the four were implants in nature, and some were of the stories that were shared were 'some of these products should have gone the PMA path, but they went the 510(k) path, and the 510(k) path is easy.' I'm just curious what are your comments about that in general.

Mike Drues: Well. Listen. Let's be honest Jon. Clearly the 510(k) has a lower regulatory burden overall then the PMA. I mean, I think it's difficult for anybody to disagree with that. Does that mean that the 510(k) is a bad pathway to market? Absolutely not. It's very appropriate for lots of different medical devices. But regrettably it has been overused. Some companies will take advantage of what the Institute of Medicine called several years ago called a loophole in the law. And regrettably, sometimes FDA, especially in the past has not pushed back on companies enough to require more. So the 510(k) is without a doubt a lower regulatory burden. This is after all why the vast majority, more than 95% of medical devices, come on to the market under the 510(k). And again, there's nothing wrong with that, it's perfectly appropriate for many medical devices, but certainly not all.

On the other hand, when it comes to the PMA, the PMA is a more rigorous pathway to market. You and I have talked about this before. It's more similar to what drug companies have to go through, although I still think it's a bit of a stretch to equate a PMA to an NDA or a BLA for drugs or biologics. But I think it is a more rigorous pathway. But it is still not perfect. One of the examples that was talked about in this particular video was a permanent implant for birth control that was brought on to the market under the PMA, and yet it experienced a litany of problems, and as a result is being off the market here in the US later this year. And there've been other examples where PMA products caused problems as well, so just because we have a regulatory burden, PMA vs 510(k) for example, doesn't necessarily mean that the device is safer. You and have I have talked about this before Jon

Jon Speer: Right.

Mike Drues: When a company gets a 510(k) clearance, when they get a De Novo, or when they a PMA approval and they become ISO, blah, blah, blah certified. That's the academic equivalent of being a C student. That just means that they're passing. That does not necessarily mean that they're making a good product, that they're making a safe or effective product. And I think we as an industry need to set the bar higher. I hear a lot of people, they talk about 'our goal is regulatory compliance.' Well, in my opinion ... or quality compliance for that matter ... In my opinion, that's a pretty low place to set the bar. That's like, you know, 'my colon is in this college courses to get a C.' You know?

Jon Speer: Right. Right. [crosstalk 00:11:11]

Mike Drues: I think we can do better than that.

Jon Speer: Right. Yeah. I'm drawn to a quote that came from the documentary that came from Dr. David Kessler. Dr. Kessler was a former FDA commissioner from 1990 - 97. And this quote was something along the lines of, "When it comes to medical devices we built a system that doesn't work." I mean, why did he say this and do you agree?

Mike Drues: Well I do have a lot of respect for Dr. Kessler. He and I have agreed on many things. Certainly not all things. I also have a lot of respect for the current FDA commissioner as well, Scott Gottlieb, although in many ways the two are diametrically opposed. Look, the system is not perfect, and this is another thing that frustrates about some folks in our industry who seem to want to somehow pretend that the system is not broken, that it cannot be improved. Clearly there are improvements that can be made. No system ... We as engineers, we learned a long time ago, I think, that nothing is perfect. You can always figure out a way to make something better. And I think the regulatory and the quality systems are exactly the same.

So I think what Dr. Kessler is meaning there, and I think it's very interesting that a former FDA commissioner under both a Republican as well as a Democratic president, cause he was commissioner for about eight years, makes such a statement publicly. I think what he's trying to do is he's trying to draw attention to this, and maybe get more people kinda like you and I are doing right now, at least talking about this. Is the system perfect? Where are the weaknesses? where are the problems? And most importantly, what can we do to try to prevent them from happening in the future. There's a famous adage, "those who forget their history are doomed to repeat it." Regrettably this seems to happen over, and over, and over again.

Jon Speer: Yeah for sure. And just hearing that comment ... At the time I was listening to that I was thinking, wait a minute there have been in recent years, there have been a lot of movement on this side of the agency to put in provisions that I think are trying to improve the system. Now I'm not saying it's perfect, I'm right there with you. But you and I have talked a lot about a pre-submission, I mean one would venture a guess that if all of these products that were featured, if that pre-submission program were in place at that time, I guess maybe this is speculation. Would these products even have been featured on a documentary? Would there have been these big challenges if a pre-submission program had been in place? And I'm not saying it pre-submission is an end all, be all, catch all, but it seems to me an example of how a program has been implemented with the intent of improving the communication between industry and FDA.

Mike Drues: Well, so as many in your audience know Jon, I'm a huge fan of the pre-sub. process. I'm down at the FDA at least once a month. Just last week I had three pre-subs. at FDA, which is kinda coincidence. So I'm a huge fan of the pre-sub. process for lots of different reasons. Whether or not if more companies would do a pre-sub. would lead to fewer problems like the ones talked about in this particular documentary, I'm not sure. I think it would be difficult to connect those dots, although maybe we could. [crosstalk 00:14:41]

Jon Speer: Okay

Mike Drues: But one or other thing I gotta just add. Although the formal pre-submission process is relatively new, the initial guidance just came out a few years ago, some of us, myself included were having advanced communications, pre-sub. meetings if you will, with the FDA 20 and 25 years ago. So there was not the formal process that we have now, but nonetheless, as I said earlier, communication is a good thing.

Jon Speer: Sure. Couple other things that I'll throw out there on this 510(k), PMA topic. Some of these devices, they're implant devices and they were cleared by 510(k), did that raise an eyebrow with you at all, or is that okay? I mean what are your thoughts about that.

Mike Drues: Well that's a great question Jon, and it's something that I've been talking about for many, many years. There are a number of permanent implants that are brought to market as a 510(k). The orthopedic industry is fraught with them. And one could easily ask the question: should any permanent implant, and by the way the regulatory definition of permanent is not what some people might think, the regulatory definition of permanent means a an indication greater than 29 days. So a permanent implant is not-

PART 1 OF 3 ENDS [00:16:04]

Mike Drues: Greater than 29 days. A permanent implant is not something that is designed to last your entire life. To quote a famous politician, it depends on what your definition of 'is' is. I'm sorry Jon, I just had a mental hiccup.

Jon Speer: Orthopedic is a good example. Orthopedic implants, something that is going to stay with that patient for the entirety of their life. There's a 510k path for those products. Make sense?

Mike Drues: Thank you for the reminder. Yeah, one could easily ask the question as a matter of law, should any permanent implant be allowed to be a 510k. Some people have made that suggestion but I'm not a fan of universal regulation like that. I'm more of a fan of a case by case basis because I can tell you this, and I've asked this question in the orthopedic companies, many of them are customers of mine.

If congress or FDA decided to raise the bar and require a PMA for the particular orthopedic implant or any implant that you're working on that might be a 510k, a [inaudible 00:17:16] is another one and pacing leads and so on. If we were to raise the bar and require a PMA, how many of your programs would be canceled? Every single person in the room raised their hand. One person said, "The program would be canceled today."

This gets back to the whole balance between regulation and innovation. It's tempting to raise the regulatory burden to try to make products that are safe and effective. That's certainly an admirable goal but on the other hand, if we raise it too much, then we run the risk of a company saying, "You know what, it's just not worth it." As a result, I said some … a few years ago that actually got me invited to do a couple of presentations on Capitol Hill and what I said was, "It's one thing to measure the number of people that are harmed or killed because they use a medical device that is not safe enough, whatever that means but how do we measure how many people are harmed or killed because they don’t have access to a medical device because we've raised the regulatory burden to the point as, I said, where the company says, "You know what? It's just not worth it for us to do."

Jon Speer: That's a good point.

Mike Drues: These are not simple problems.

Jon Speer: For sure. I think on that topic too, I mentioned the clinical side of things. There was a statement or actually a few times throughout the documentary that almost on disbelief that a medical device could get to market without having clinical data, human clinical data. Is that pragmatic? Does that make sense for products? What happens if there is a knee-jerk reaction to this and now all of a sudden companies are being asked to provide more human clinical data to support their products getting into the market. I think you have a case, don’t you?

Mike Drues: Yes, and you know Jon, that's exactly what's happening in the EU right now across the board. They are expecting more clinical data either pre and/or post market. In part, for all of the reasons that were talked about in this particular documentary whereas in some ways, the US right now is going in the opposite direction. When Scott Gottlieb, I believe this past December, was out talking about what he calls the alternative 510k, which basically is a reincarnation of the abbreviated 510k.

Whether or not all medical devices should require some clinical data, I'll leave that as a rhetorical question. I personally, as bio-medical engineer, as I said I do not like universal regulation like that. There are many medical devices where I think it is totally unnecessary to have clinical data. In those situations, when FDA asks for clinical data, I will very politely, but also very strongly push back and say, "Look, clinical data is not necessary for all of the following reasons." This is something that I do frequently.

On the other hand, there are other medical devices … what do you want to call it? A 510k or is it [inaudible 00:20:30] or a PMA, or an HDE or whatever it is. I could care less. There are other medical devices that in my opinion as a professional bio-medical engineer do require clinical data either because of the pathophysiology because of the newness of the technology, because of the risk, what have you.

I'm a big fan of doing what makes sense based on the biology and engineering. One of the examples I'll share with you Jon, I mentioned I do a lot of pre-subs at the FDA. Just last week, I have to be a little careful what I say here, but just last week, we took a medical device. The FDA as a pre-sub, this was actually for a device already on the market. It's been on the market for about a dozen years. The company would like to do a label expansion to add a new indication to the product's label.

Now this particular device Jon, it's not a permanent but it is a device that goes inside of patients' body. This has been used more than a million times both in the United States as well as around the world. More than a million times including for this particular use that we want to add to the label because right now it's technically an off label use. Yet, we have in the literature about 700,000 reports of physicians using this particular device off label for this particular indication.

The company is wanting to go to the FDA to update the label in order to better reflect what physicians, what surgeons do in the real world. FDA is pushing back. They say they want clinical data in order to show this.

Jon Speer: Oh, wow.

Mike Drues: I said, "With all due respect, what the hell can you possibly expect to find in a clinical trial that we don’t already know with these over a million uses, 700,000 alone for this particular off label use." Anyway, part of the reason why I shared this story with you and your audience Jon is because after the meeting, keep in mind that any of the reviewers that FDA are personal friends of mine, some of which we go back to Graduate School.

One of them shared with me, and again I have to be very careful what I say here. That part of the reason why FDA is asking for this as being very cautious, some people might even argue overly cautious is because of press, like this particular documentary that we're talking about that just aired a few weeks ago. FDA is painfully aware of the decisions that they make and the ramifications. I often like to compare the FDA and the CIA because the FDA and the CIA are very similar in the sense that when the CIA does their job, nobody knows about it.

When the CIA does not do their job, everybody knows about it. FDA is very similar and these kinds of documentaries and articles and the literature, and by the way, this particular documentary is absolutely not new. There have been a laundry list of articles and other documentaries going back to that 1970s when FDA first started regulating medical devices, questioning the whole medical device regulatory framework.

Anyway, it's absolutely nothing new. Just because somebody watches a video like this and dismisses it because they think that it's one sided or what have you, there's two things that they’ve got to remember. First of all, this is what the public is seeing because most regular people, they don’t have the knowledge of our industry that you and I do. Second of all, it has ramifications on them. Whether they realize it or not, whether they want to admit it or not, in part on how they're treated by the regulatory agencies either here in the United States or perhaps even in other parts of the world as well.

Jon Speer: Yeah, that's helpful. I think to transition to the next topic I wanted to explore a little bit, let's talk a little bit about some of the systemic breakdowns of these quality systems that were in place at these companies because to me, seeing or hearing these stories, there was that one device in particular. I think it said something in 2017, they had 12,000 adverse events. I'm like, "Are you kidding me? That's a lot." For me …

Mike Drues: Hold on, Jon. I'm sorry to interrupt.

Jon Speer: Yeah, go ahead.

Mike Drues: Once again, you and I have talked about this before. We have to be very, very careful about over-generalizing. You're exactly right. On the surface, 12,000 adverse events seems like an awful lot but my question is what exactly were those adverse events? Some of those might be totally trivial. Others might be not. We just have to be careful about overly generalizing. I'm sorry, please continue.

Jon Speer: No, I agree with you but at the same time, if I'll guess I'll speak from my own opinion here that if I worked on a device that had, I'll just say a significant number of adverse events. Number one, I would want to make sure that I did a thorough complaint investigation to understand why. We don’t know in this case if the company did or did not do a thorough complaint investigation on all those vents. We don’t know.

Mike Drues: Jon, are you suggesting that a company should be required to do what you call a thorough investigation on each of those 12,000 adverse events in that year alone?

Jon Speer: Well, it depends on the situation. For sure. It depends on to your point, what were the events? If it's event number one is something first time that we've learned about this particular type of event, then absolutely I should do an investigation but if it's something that has come to us before that we've already investigated then perhaps not. The regulations are very clear that we need to investigate all complaints. It doesn’t say that you have to repeat an investigation over and over again if you have already investigated that particular issue.

Mike Drues: Well, I'll give you a quick example from my world right now Jon. I'm working with a small company in California. Literally as we speak we just had this conversation a few days ago in fact. They are, long story short, in my opinion doing all the right things from a regulatory and quality perspective. They're good people, they're conscientious, they're not interested just in simply meeting the regulatory or quality requirements.

They do care about people's lives and blah, blah, blah. Anyway, on a very recent inspection, they got four dings four 43s, one of them being that the company, and I actually advocate this strategy, the company has put together a fairly robust weight triage their complaints so that they can decide which complaints are worth, to use your phrase, a thorough investigation and which can be dismissed.

Anyway, the FDA inspector said, "No you can't do that. You have to thoroughly investigate every single one." This is a small company Jon. We're not talking about 12,000 events per year but nonetheless if that's going to be standard, this company is probably not going to be able to stay in business because in my opinion it just doesn’t make sense to treat every problem as if it was equal.

We have to have an investigation, yes but we should not require a thorough investigation, whatever the word "thorough" means of each and every one. There's got to be some common sense here.

Jon Speer: Well, I agree. It seems to me that in that case that you decided. My opinion is that’s an over-application of regulations. That seems to me of an example of where more regulations are being applied when it's not required. Again, I'm speculating here but I think a lot of companies struggle with this in large part because the systems that they have in place. If I were to investigate in something and a new event comes in that is just like the thing that I already investigated, I can reference that.

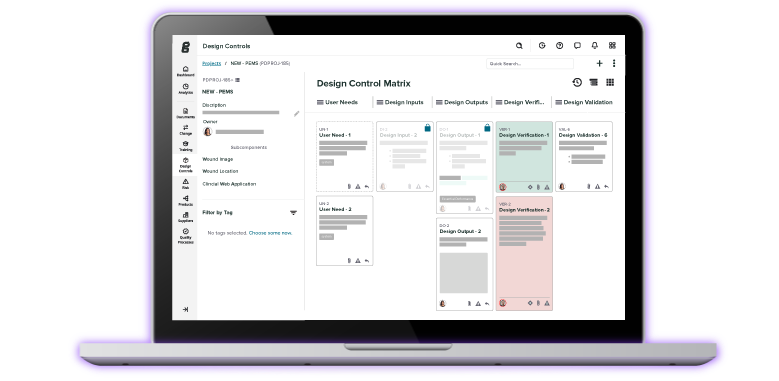

The design of my quality system is going to be important, where and how I manage my documentation and records is going to be important. Frankly, this is why we built Greenlight Guru: eQMS software platform is to be a single source of truth so that you don’t have to do redundant, repetitive work that's already been done. You can simply link to and reference that information and connect those things together.

I think that's important. That's one thing that I will challenge companies is make sure that you built a thorough robust complaint handling process but to my Mike's point and that we're illustrating here is make sure that you’ve designed that. Even if you get a little bit of pushback from FDA regulatory agencies, challenge that notion in a healthy way. Make sure that you're meeting or actually exceeding the intent of the regulation.

If you feel as though you're being suggested to go above and beyond, something that's a bit overly burdensome, that's something to not just cave in and accept as the rule. Do have a healthy understanding of how to apply the regulations.

Mike Drues: Once again Jon, you and I are singing exactly the same song but perhaps in just a slightly different key. What I'm suggesting here, coming from a medical background myself, I used to say to my medical students, when a patient presents to the emergency room, the first thing that's supposed to happen is they have a quick initial assessment. If it looks like something like a heart attack or ischemic stroke or something that's a major problem right away, they're obviously treated right away.

On the other hand, if they have a splinter in their finger or something, then they might be waiting around for hours. This is a whole concept of triage. That's what I'm trying to apply here because it's just not realistic nor does it make sense to apply all of these regulations equally. I'll share with you another example from just this past week. We had an FDA employee. I won't say what level this person was but this person was a fairly significant level within the FDA, made the statement that regulation is regulation. There is no room for interpretation.

Jon Speer: Oh, wow.

Mike Drues: This is somebody who is on the payroll at the FDA and those of us in the company side of the table, we're just all shaking your heads. It's like, "What did you say and where did you work? Where do you work?" Anyway, this is a problem.

Jon Speer: For sure, and I think companies can do themselves a service by really truly understanding their interpretation of the regulations, part 820, part 803, part 806 and so on as it applies to their products and processes. Folks if you have any doubt about that, you can reach out to folks like Mike, you can reach out to folks like Mike. We've been through this and neither Mike nor I have any interest in helping you implement overly burdensome systems.

We want you to meet the intent. We want you to make sure that the processes that you put in place improve the quality of life and ultimately are addressing patient needs. That's the whole premise. That's why we're in the medical device industry. And I like your point about triage. I mean, to say it a slightly different way, this is really what is intended and what ISO 13485:2016 talks about applying a risk-based approach to your QMS, applying a risk-based approach to your complaint handling system is truly understanding the ramifications of the event that's come to your attention.

Not all events are created equal for sure. But for those significant events ... There was some discussion on the documentary about the MDR reporting to the FDA, and I think there was even a statement that was made that I disagree with. They made it sound as though it was voluntary across that board, and that's absolutely not the case.

So any thoughts about some of the comments that were made about the MDR program?

Mike Drues: Well, just to be clear, Jon. You and I have talked about this in previous podcasts, voluntary reporting across the board is an incorrect statement. So that I agree with you. Companies are required to report adverse events to the FDA, but those are obviously limited to the ones that they are aware of.

Physicians, on the other hand, are not required to report problems. Let's not parse words by talking about AEs or SAEs or whatever. Physicians are not, as a general rule, required to report problems. Perhaps they should be. But if they were, that's not something that FDA could require because FDA after all does not regulate the practice of medicine.

One of the interesting statistics in the documentary ... As a result of this, they said that only about 3% to 4% of adverse events are actually reported to the FDA. Now, I haven't fact-checked that particular statement, but I can tell you-

Jon Speer: So how would you know that? How would you know that?

Mike Drues: But that's a good question because it's like, how do you measure what you can't measure? But it does make sense why because there are similar statistics on the drug side of the world that depending on the source maybe only 8% to 10% of adverse events associated with drugs are actually reported to the FDA. And in this particular documentary, they even suggested that for significant adverse events, it might even be lower than that.

So one thing that all of us in this industry have to keep in mind is we can only view the universe through our own particular set of eyeglasses. We can only see what's visible to us, or in this case, what's reported to us. Just because there are not problems associated with ... Sorry, let me say it this way. Just because there are not problems reported to you as a manufacturer about your medical device does not necessarily mean that there aren't problems.

And I have suggested in some of the product liability law cases, lawsuits that I'm involved with, that companies should not be passive in simply waiting for problems to be reported to them. Companies should actually be active, especially in very critical life-supporting or life-sustaining technologies, where the company actually goes out and talks to their customers and says, "Look, are you having problems? Or can you tell us about the problems?" and so on.

So this is an area where I think we can use some improvement as well, although to be fair, as you can imagine, Jon, it's a difficult sell to get a company to do that because why go looking for a problem? But again, we have to be responsible professionals.

Jon Speer: Well, there's two points I want to dive into just a little bit more depth on based on what you just shared. First of all, this is a systemic issue where companies can improve. To your point, I think most companies are reacting to situations rather than getting ahead of it and being proactive.

And it begs the question for those of you listening who are in the industry, do you want to be the subject of the next documentary about devices gone bad? If the answer is no, which I assume that it is, then I would encourage you to be more proactive in trying to identify potential issues before they become big deals for sure. That's my advice.

The second thing that you ... You dropped it in a comment, but it's surprising to me how many people do not realize this: FDA does not have jurisdiction over physicians and the practice of medicine. Can you speak a moment about that?

Mike Drues: Sure. Simply put, Jon, FDA as I said does not regulate the practice of medicine. That is, FDA cannot tell physicians what to do. They can only tell us, meaning industry, what to do. And there are some exceptions for example if the practice of medicine is practiced by a person, that's true. However, if the practice of medicine is practiced by a device, then the FDA is all over it, and I have countless examples where we have taken devices to the FDA that do absolutely nothing more than what physicians or surgeons have done themselves in the past.

Yet FDA is very critical. They require a lot of scrutiny of it because when it's done by the surgeon him or herself, FDA has nothing to do with it. But when the same thing is done by a device, FDA has everything to do with it. So FDA regulates the practice of medicine when it's practiced by a person but when it's not practiced by a person, all bets are off.

Jon Speer: So folks, it's interesting to think about, but realize that you as a medical device company, your responsibility is to make sure that product is safe and effective and ideally that the people who are going to use it, the physicians, the clinicians, and so on, as best as you possibly can, it's obvious, as intuitive as possible. And when you start to observe the product being used against the way you designed it or intended it, this is the time to be proactive.

I'll leave that there for now because that's a whole different topic.

Mike Drues: Well, actually, Jon, I know we're coming close to the end. I would like to take that just a half a step further. One of the things that's boggled my mind in our industry for a long time is that we separate the ... FDA regulates the medical devices that we make, but they do not regulate the procedures in which they're used because the procedure is the practice of medicine. But to me, you shouldn't have to have a PhD in biomedical engineering, Jon, to appreciate that that makes absolutely no sense.

How can you separate the device from the procedure in which it's used? It just makes no sense. And yet we've been doing that for decades.

Let me take that a step further. Back to the documentary, so many of the devices that they featured were permanent implants and several of them, when the implant was causing problems, it would be very difficult or perhaps even impossible to take that permanent implant out. So the question is, what can we as engineers and as an industry do about this?

Nevermind a regulatory solution, this to me is an engineering problem. So should we be required to ...? When a medical device, especially a permanent implant comes to the market, whether it's a [inaudible 00:39:37], an [inaudible 00:39:37] PMA ... I don't care what ... should the manufacturer be required to provide some sort of a removal procedure?

Obviously they have to include an implantation procedure that's vetted, that's validated either you have a usability study or a clinical trial or both. But what about the idea of having them provide a removal procedure? "Hey, in case something happens, Dr. So-and-so, this is how you can get it out."

And taking it even a tiny bit further, Jon, and I would love to hear your thoughts on this as well. On the technology side, there's been a growing ... Sorry, there's been ongoing interest for several decades on designing devices to be retrievable. So what's my definition of a retrievable device? This has actually been adopted by CDRH as their in-house definition. It's not in the CFR yet. Maybe somebody I should live so long it might go in there.

But every device can be retrieved. The question is how much effort should we take to take it out? So my definition of a retrievable device is a device that requires no more effort to take it out than what was required to put it in. If you're putting in a device minimally invasively with a laparoscope or an endoscope or a catheter, it should be able to be taken out minimally invasively as well. So that's another suggestion I would encourage our industry as well as the FDA to think about ... is maybe we should have a requirement for having some sort of a retrieval procedure, removal procedure that a surgeon can follow in the event that some kind of a problem occurs?

Jon Speer: Definitely food for thought, so something to think about. And Mike, I know we're up on our time for today, but kind of as a parting comment, do we need more regulation? One of the things that was hinted is that there's not enough regulations in place for the medical device industry, so like I said at the onset, I have a pretty idea of where I think you stand on this topic. But I'll let you speak for yourself. Do we need more regulation in the medical device industry?

Mike Drues: Well, thank you, Jon. Yeah, for those of you in your audience that don't know me, this might sound a little hypocritical. You're probably thinking, "This guy's a regulatory consultant, so of course he's going to be a big fan of more regulation."

Nothing can be further from the truth. When I started out in this business, Jon, a little over 25 years ago as an R&D engineer, we had a heck of a lot less regulation than we have today. The design controls did not even exist. They went into effect in 1997, and yet somehow ... I don't know how this happened, Jon ... we were able to go get reasonably safe and effective medical devices onto the market.

Fast-forward nearly three decades later, we have thousands and thousands of pages of regulation. But the question is, are our devices really any safe or more effective? Is the world a better place? I'll leave that for your audience as a rhetorical question.

But simply put, I don't believe that more regulation is the solution. As a matter of fact, some people have criticized President Trump for the goal of for every one new regulation, two old regulations have to be removed. I hear a lot of people, they argue how much regulation. Some people say we don't have enough regulation. Other people say we have too much regulation. In my opinion, Jon, as an engineer looking at the root cause, I think that's the totally wrong question that we should be asking.

Jon Speer: Totally wrong question.

Mike Drues: I'm sorry?

Jon Speer: No, I was just saying, totally wrong question. Wrong lens.

Mike Drues: Yeah, totally wrong question. The question that I like to ask is, of the regulation that we do have today, does it make sense? Every week almost every day, as a professional biomedical engineer as well as a regulatory consultant, I read regulation that makes absolutely no sense. And yet people follow it anyway. Is that a problem with the system, or is that a problem with us?

So I'm a big fan of having the right regulation, and I'm also a big fan of doing what makes sense whether it happens to be required by FDA or not.

Jon Speer: Yeah, that's a really good thought. And folks, really regulations aside, as medical device professionals, our responsibility is to make sure that the medical devices that we design, develop, and manufacture and safe and effective and meet the indications for use. I know that's a broad oversimplification, but as a medical device professional, that's what we need to do.

We need to make sure that the products-

Mike Drues: Easy for the politicians to say, Jon. But what do those words really mean in the real world?

Jon Speer: Well, and that's the art. And the art is making sure that you have designed the appropriate processes and implemented the appropriate systems and have the right level of education to understand what that means and to apply ... With everything you do as a medical device professional, ask yourself the question, is this a good decision for the patient?

That's the moral compass that I try to follow each and every day with everything that I do in the medical device industry. And I hope all of you listening are doing that as well. To Mike's earlier point, if you're just focused on compliance, that's the equivalent of a C student. We believe that as well at www.greenlight.guru. It's why we have developed an eQMS platform specifically for the medical device industry so that you can elevate your game to being an A student. So that you can shift from just being focused on compliance and actually elevate and focus on true quality and make sure that the products that you're designing, developing, manufacturing are going to improve the quality of patients' lives.

Mike, I appreciate you taking a few moments to chat with me today about this documentary. Folks, if you want to learn more about how Mike Drues and his expertise can be an asset to your company, I would encourage you to reach out to him at Vascular Sciences. This has been Jon Speer, your host, the founder and VP of quality and regulatory at Greenlight Guru, and you have been listening to the Global Medical Device podcast.

ABOUT THE GLOBAL MEDICAL DEVICE PODCAST:

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Nick Tippmann is an experienced marketing professional lauded by colleagues, peers, and medical device professionals alike for his strategic contributions to Greenlight Guru from the time of the company’s inception. Previous to Greenlight Guru, he co-founded and led a media and event production company that was later...