Significant Risk vs. Nonsignificant Risk Devices - What's the Difference?

.png?width=4800&name=podcast_standard%20(2).png)

Do you understand the difference between significant risk and nonsignificant risk when it comes to the development and design of your medical devices? It’s important to classify devices properly, and the difference between SR and NSR is not always well-defined.

Today, our guest will help medical device companies differentiate between these two classifications.

Mike Drues, president of Vascular Sciences, has been a frequent guest on our show. He’s an expert in compliance, medical technology and regulatory compliances.

Mike works regularly with the FDA, Canada Health, and other international regulatory agencies, and today he is sharing his insight on SR vs. NSR, as well as how this affects your development processes for your medical devices.

Listen Now:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some highlights of this episode include:

- The difference between significant and nonsignificant risk, and how you can differentiate between the two.

- Who decides whether a device has a significant or nonsignificant risk. (Hint: It’s not the FDA!)

- Tips on analyzing, documenting, and finding experts to help you determine whether you are dealing with SR and NSR, as well as tips on notifying the FDA through the pre-submission process.

- Information about the Institutional Review Board and how they are involved in the SR vs. NSR differentiation.

- Thoughts on running clinical trials outside of the USA: advantages, disadvantages, and practicalities.

Links:

Significant Risk and Nonsignificant Risk

Medical Device Studies FDA Guidance

Memorable quotes from this episode:

“Our goal should not be to avoid the FDA; our goal should be to work with them.”

“In many cases, there aren’t devices that are the same... at the end of the day, it’s our determination.”

“Ask yourself if you’d feel comfortable using a clinical device on a family member, a friend, or yourself... we are talking about people’s lives here.”

Transcription:

Announcer: Welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast, where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Jon Speer: Alright, I'm gonna keep it simple on this intro today. Topic on the Global Medical Device Podcast; significant risk versus non-significant risk and what that means to your clinical investigation and your medical device design and development efforts. If that's important to you, then you're gonna enjoy this conversation that I had with Mike Drues from Vascular Sciences.

Jon Speer: Hello and welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast, this is your host Jon Speer, the Founder and VP of Quality and Regulatory at Greenlight.guru. Joining me this morning on the podcast is Mike Drues. Mike Drues you're probably a familiar guest if you've listened to any of the podcasts before and based on some of the wonderful metrics that we've been collecting there's a good chance you've listened to many of these episodes before. So Mike is with Vascular Sciences, you'll recognize his voice and his contributions to the industry. Just do a quick search for his name, D-R-U-E-S, and you'll find some wonderful content. I know last time Mike and I spoke, we talked about his bucket methodology for risk management. It's a wonderful article. Definitely encourage you to check that out. But Mike does consulting with regulatory bodies, FDA, Health Canada and he also works with med device companies. So Mike, welcome back to the show.

Mike Drues: Well, thank you, Jon, always a pleasure to be with you and your audience and thanks for continuing to have me back.

Jon Speer: Yeah, I always mark these times on our calendar. This is an enjoyable point in the week when you and I get to chat. So I look forward to these as well.

Mike Drues: I do too. Thanks, Jon.

Jon Speer: Alright, well today we're gonna dive into a topic that certainly many medical device companies are very interested in. There's always this quest for getting real clinical data on a medical device, obviously that clinical data, that real life experience seems to have more meaning in the grand context of a product versus just that benchtop testing that sometimes gets conducted. And so today we're gonna jump into this topic of nonsignificant risk versus significant risk. We're gonna talk about the implication from an IDE perspective. We'll talk about all the acronyms that go along with that. And we'll dive into some other aspects of what do you need to do from a design control standpoint. Is that okay, Mike?

Mike Drues: That sounds great.

Jon Speer: Alright, Mike, so there is this context that's out there, SR versus NSR, significant risk versus nonsignificant risk. So if you could take a moment or two and get us all calibrated a bit on what's the difference?

Mike Drues: I'd be happy to Jon. So as you and your audience know there's a number of ways that we can sort of separate or classify, if you will, medical devices. One is via the classification system, class one, class two, class three, which is at least theoretically based on risk although, as we talked about in our last podcast, risk has many different connotations, and there's a lot of exceptions to that, but the classification system is one way. A second way is differentiating devices in terms of significant risk, SR, versus nonsignificant risk, NSR, devices. Interestingly enough, the definition of risk in the context of SR versus NSR is not very well defined as we discussed in that risk podcast, and I would point your audience if they have not listened to it to listen to that podcast, before making a determination of significant risk versus nonsignificant risk. But as we'll get into in this particular discussion, the ramifications of that decision are very important in terms of what you have to do and who you have to notify during this process and so on.

Jon Speer: Yeah, just to go back on that a little bit, you describe one of your buckets, if you will, and I'm using air quotes for those of you who can't see at home, but one of the buckets has to do from a clinical perspective and from the end user perspective.

Mike Drues: That's correct, I can at a very, very high level recap those three buckets. The first bucket is the probability of direct harm. The probability of direct arm. And that's the most obvious connotation of risk that people think of. That's the type of risk that we think about in the design controls, for example, and that is what is the probability that your medical device causes harm directly to the patient? Usually it's the patient, occasionally it's the caregiver. The second bucket is the probability of harm of not using. This is a PMA requirement, it is not a 510K, or De Novo requirement, yet, although there is some discussion of putting it in there. So if we don't use our device, what other options do we have? Not just other device options, but maybe there are surgical procedures, maybe there are medications that we can use instead.

Mike Drues: And the third bucket is the probability of providing the wrong information, the probability of providing harm because of the wrong information. This is endemic in all diagnostic products, including telemetry like EKG monitors, including imaging systems, including in vitro diagnostics like cancer detection, including many of the mobile medical apps, and so on and so on. So as I mentioned a moment ago, with regard to SR versus NSR, when you look at the guidances that have come out over the years in this area, the type of risk is not specific in making that determination. But my standard advice is, consider all three of those buckets when you're making an SR versus NSR determination.

Jon Speer: Yeah, so I guess one way to sum that up is when you as med device company are evaluating significant risk versus nonsignificant risk, be sure to document those decisions. And I guess that's the next question that comes to mind for me is, who gets to determine significant risk versus nonsignificant risk? And let me preface this by saying I talk to a lot of medical device companies, as do you, just about every medical device company I talk to, regardless of what they're designing and developing believes that they can do a clinical investigation and call it nonsignificant risk. So determine that.

Mike Drues: And as we'll talk about, Jon, I think the primary reason is because they want to avoid doing an IDE and they want to avoid dealing with the FDA as much as possible, which on a personal note, I think is very unfortunate. I don't think that an IDE, or more importantly, the FDA, is something that we should... Our goal should not be to avoid them, rather our goal should be to work together with them. But as we've talked about many times, my caveat in that is, "Tell, don't ask. Lead don't follow." But the answer to your question Jon of who decides whether the device is significant risk versus nonsignificant risk. Ironic as it might sound it's not the FDA, it's not the IRB, or the Institutional Review Board, it's us the manufacturer. To a certain extent that is like putting the fox in charge of the hen house but that is exactly what the regulation says. And by the way, one of the reasons why it's important, if I can take this a half a step further, I think one of the reasons why a lot of companies will try to spin their device as a nonsignificant risk device is so that they don't have to involve the FDA, at least not early on, and they don't have to do an IDE, an Investigational Device Exemption, because a nonsignificant risk device is IDE exempt.

Mike Drues: But, let me say this much. In the NSR devices that I have worked on, and I've worked on a number of them over the years, I still strongly, strongly recommend taking it to the FDA in advance, prophylactically, as I like to say, as a matter of professional courtesy, before you begin your clinical trial. Not to ask them their permission. Not to say, "Is this okay?" Because if your device truly is NSR you do not need their permission, but rather I wanna keep them in the loop and I wanna make sure that we're all on the same page because I've seen it happen, as I'm sure you probably have as well Jon, where companies will assume their device is NSR, they will do their clinical trial, afterwards they will in the submission send that data to the FDA only to find FDA comes back and says, "Well, we would like... We want to see this piece of information that you did not collect." Or even... Or even worse, FDA says, "Well gee, we don't see this as nonsignificant risk, we see this as significant risk." And now you have some real problems.

Jon Speer: Now that is invalid and do over and all that sort of thing.

Mike Drues: Exactly, and in extreme cases... And again, this does not happen often but it does happen occasionally. In extreme cases when that happens, you might not be dealing with just the FDA, you might be dealing with the Department of Justice as well.

Jon Speer: Yeah.

Mike Drues: And those guys don't mess around.

Jon Speer: Yeah. Well, they do carry badges and I'm sure some of them carry guns, but anyway. Alright, so this determination of SR versus NSR, so I as med device company get to make that decision. I'm guessing that... I know there's a guidance document that exists to help provide some context and some direction on that, but what else do I... Where else can I go? Or is that guidance document really it?

Mike Drues: No, that's a good question. There's a few guidances and we can provide to your audience links to guidances along with the podcast. In addition to that, though, it's always prudent to do your regulatory due diligence. Your homework so to speak. So if you're working in an area where there are already other devices that are similar to yours, that's a very good place to look to see what the precedent is. But in many cases, there aren't devices that are exactly the same or even close, and so at the end of the day it really is our determination. But this is an area, Jon, and you mentioned this earlier, documentation is very important, you need to go through that analysis. If you wanna use my "three bucket approach" terrific, if you wanna use a different approach, that's fine, as well. But you need to use some analysis and you need to document that.

Mike Drues: And I'm a big fan of using subject matter experts. So you can identify some top people from either academic institutions, they might be engineers, they might be clinicians, depending on the device or the technology that you're working on. And what I would suggest in this particular situation, I do not ask SMEs to write letters to say anything about my device and I certainly do not want them to say my device is the greatest thing since sliced bread. Because that's inherently biased. Instead, in this particular context, what I would be asking them, is to say, "Based on my understanding of the labeling as well as the technology of the device, it makes sense to consider this particular device a nonsignificant risk device for the following reasons," and so on. And I would put all of that information into your... To use a phrase from a different podcast. Your letter to file, that way, if in the future somebody comes knocking on your door and says, "Hey we noticed that you are doing a clinical trial here of this device. We don't remember you ever coming and talking to us about it, what the heck is going on?" And now you can pull this file out, if you make it very obvious that you didn't forget anything you're not hiding anything. It's just a matter of a business decision that you're not notifying FDA. And there we go.

Jon Speer: And let's go back to that point you made a few moments ago, if you determine that your study that you want to do is nonsignificant risk, you suggest a courtesy of just notifying the FDA. And so let's talk a bit about that and we've talked about the topic of a pre-submission before. Is that the vehicle by which you would notify FDA regarding your nonsignificant risk study?

Mike Drues: I think most likely. Nowadays FDA has formalized many of the methods of communication with the agency, which to a certain extent I think is unfortunate in my opinion. I think we've made it too difficult for companies and the FDA to talk to one another. But short answer is yes, I think the pre-sub process is probably the most appropriate method to do this, whether the company wants to have a pre-sub dedicated just specifically to this SR versus an NSR or not ultimately that's up to them. Usually that's not the case. Usually what I will do is I will present the regulatory plan, the R&D plan, including the testing matrix and the clinical trial, or the lack thereof, all within the same pre-sub.

Jon Speer: Okay. That makes sense.

Mike Drues: But if you have a device where you are truly in the gray area between SR versus NSR and it could go either way, and you're a little fearful that maybe some of our friends on the other side of the table might see it differently than you do. In that particular case, you might decide to have a pre-sub meeting dedicated just to talking about this particular topic. One other thing I think we should mention for your audience, Jon, is, even if your device is a nonsignificant device, and in that case, let me be crystal clear, there is no obligation, there is no regulatory mandate to talk to the FDA. That's just my personal recommendation. You still have an obligation to talk to the IRB, the Institutional Review Board.

Jon Speer: Yeah, and I think there are a... It's probably worth spending a moment or two talking a little bit about what an IRB is and I'm gonna make an assumption we have some listeners that they may be venturing into this for the very first time. Granted there probably are quite a few who have been down this path many many times before, but if I wanna do a clinical research on my product or investigation of some sort, it's not as simple as just going down to the major hospital in my city and finding somebody and say, "Hey, will you... I've got some product will you do a study on this?" there's a little bit more involved than that.

Mike Drues: There is Jon. In a nutshell... And we could spend a lot of time talking about IRBs. But in a nutshell, the Institutional Review Board or IRB is sort of a back up, a safety valve, if you will, to the FDA. Unlike the FDA, the IRB exists at the level of the local institution, the hospital, the medical school, the clinic, wherever you might be doing your particular clinical study. And their most important role is to ensure the safety of the patients participating in the clinical trial at that particular local institution. And they will be looking at a lot of the same information that the FDA will be looking at. But here's the thing, and this is why I think it's important in our conversation today of SR versus NSR. If your device is nonsignificant risk, then as we've discussed, there is no obligation to take this to the FDA. If you do not take this to the FDA the only group that stands between you and the patient is the IRB. So in my opinion, for nonsignificant risk devices, the role of the IRB becomes even more important when you're working on a significant risk device.

Mike Drues: And in that scenario where the FDA is not involved the IRB again, in my opinion, has an obligation to look at many of the things that FDA would have looked at anyway that... But because it's a nonsignificant risk they're not looking at. So even very basic kinds of things like biocompatibility, like usability and so on, and so on. Normally, those are just tick box on the FDA form. But the FDA is not involved here, so if the IRB is doing their job, and regrettably, they don't always do their job. But if they're doing their job, they should be looking at the same information. So, bottom line, you mentioned earlier, Jon, that a number of your customers and unfortunately, mine as well, will sometimes try to work on an NSR device to avoid the FDA, but the amount of work that the company has to provide, whether it's the FDA or IRB should be, for the most part, the same.

Jon Speer: Yeah.

Mike Drues: Testing and so on. It's not a shortcut in that regard.

Jon Speer: And I think that, like you said, sometimes people... Or I'm speculating. Sometimes companies think, "Oh, I can go the NSR route because it's gonna be simpler and easier and faster," and all those sort of things. And generally speaking there's still, like you said, there's still some obligations and some IRBs are better than others. Let's face it. But even if the IRB is doing their job or whether or not they're looking at the details to demonstrate the product's safe, it is our responsibility as medical device professionals to be able to present that case. We talked about documenting the risk rationale and analysis of whether or not the item is significant versus nonsignificant risk, as well as harm to patient and clinician and all of those different aspects of how the product is to be used that all needs to be captured. But we also need to be able to show, objectively, that the product is actually safe for clinical investigation. You mentioned biocompatibility as one component, and for many devices that certainly is a factor. In other cases, electronic devices, for example, electrical safety may come to bear, we may need to have some bench testing and animal testing before we even go to the clinical setting. So there's a lot of factors that we have to weigh in to get to that point where we're ready to do that clinical investigation.

Mike Drues: Absolutely correct, Jon. I could not agree more. And just one thing I would like to amplify because I think there is some misunderstanding in the industry about this. You alluded to speed to market, a moment ago, and some folks think that if you can avoid the FDA and avoid doing an IDE, you'll get through this process faster. Well, that's not necessarily the case and here's why, because, although you might think, I don't mean you Jon, but I mean folks is the industry might think that it's a slow process getting through the FDA, which it certainly can be sometimes, at least there are some because of MDUFA, the Medical Device User Fee Amendments and so on, at least there are some requirements to keep the ball rolling. Unfortunately, in the IRB world, there are no similar requirements.

Mike Drues: And it can happen. Now, I'm assuming that we're talking about an institutional IRB, as opposed to a commercial IRB, commercial IRBs are a little bit different, but that's beyond the scope of our discussion here, it can be pretty time consuming to get through the IRB process. And in addition to that, at least FDA has, or are supposed to have, the subject matter expertise in the different areas, biocompatibility, you mentioned electrical safety testing, and so on and so on. Whether an IRB has those experts, at least in my experience, that's usually not the case.

Jon Speer: Right. Mine as well. But the expertise should lie within the medical device company will have an internal at your company leverage resources, people like Mike Drues and Jon Speer for example, or other testing firms and resources who can help you in that regard, but there is an expected body of knowledge that you're building in order to get to that clinical.

Mike Drues: Absolutely, so to wrap up this part of our discussion, I think if the audience just simply remembers that the most important function of the IRB is to ensure the safety of the patients participating in the clinical trial, locally at that particular hospital, medical school, what have you. That's probably a good place to start.

Jon Speer: Yeah, and keep in mind folks that when we talk about device safety and we talk about risk management, we talk about... We didn't really explicitly describe design freeze but there needs to be some level of, quote, design freeze before you go and start doing clinical investigations as well. You can't build a device and take it to the clinic and do some testing, gather some data and then go back and iterate and come back, go back and iterate. That's just not a practical way to do that, so...

Mike Drues: That's a good point, Jon. Maybe this could be the topic of a different discussion. But in the medical device world, because of the iterative nature, the evolutionary nature of our device design, we tend to be a little bit sloppy when it comes to design freeze, especially when it gets to the clinical trials. If you compare what we do in devices to what we do in drugs, there is no... We don't have a snowball's chance in you know where changing a molecule in the... Or even for that matter changing a manufacturing process, in the middle of a clinical trial. So you have to have things really buttoned up, locked down in the drugs and biologics. We don't have that level of rigidity in the medical device world, which is probably a good thing, but we need to have some. And speaking of that, what does your audience need to understand, Jon, in terms of design controls for... In the determination between significant risk versus nonsignificant risk?

Jon Speer: Sure, so I always... People always ask. "Well, what can I do with this prototype?" And, "Can I do clinical work and can I do this and can I do animal studies?" And that's really a question I always flip back on them is if you're building a device, what do you hope to achieve? How many are you building? Are you building three? Are you building 300? What kind of information do you want to learn from this product? And the answer to that is very important because if you're just doing some bench testing then that's a completely different answer than if you want to go and do clinical investigation. If you're gonna go do clinical investigation in the design control terminology, that really fits in that topic of design validation, and that design validation, is demonstrating that the product that I have developed meets those user needs. I designed the correct product. That's what I'm trying to demonstrate through that clinical investigation.

Jon Speer: And so that would imply that you have things like your user needs nailed down, you have your product design input requirements, performance criteria, all of that information would be locked down. You know, all the materials and components of that particular product. And that's captured and documented. You've done some... We talked about biocompatibility, electrical safety, you've done other testing and activities to show that the product is safe. That's design verification and you've had design reviews throughout that process. So all of that should be documented. I want you to understand you may get to that design freeze and you may be building these units in your production like settings for supporting your clinical investigation. It's not to imply that you can't go back and change before you go to market, but you should have a device that is very much a candidate for release, if you're going to this level of a clinical investigation.

Mike Drues: Well, once again, Jon, I could not agree with you more. You did a great job at a high level of ticking through the major steps in what we're looking for before beginning a clinical trial. Let me just offer it to the audience in a slightly different way. Maybe even at a slightly higher level. All of the details that you just ticked through are very, very important. But I look at it very simply from a philosophical perspective. Even in a clinical trial, would you feel comfortable in the device that you're working on, using this in a clinical trial on a family member, on a friend, perhaps even on yourself? And if the answer to that question is, yes, I think largely we're good to go. If the answer is I'm not sure, then maybe we need a little more work to do. Because even in a clinical trial when there is still a certain degree of risk and so on and so on. At the end of the day, we are still talking about people's lives here.

Jon Speer: We are.

Mike Drues: Maybe that might be a nice segue to our last question for today. Speaking of people in clinical trials, we both know, Jon, that there is a growing trend in our industry for people to do clinical trials outside the United States, and certainly there are advantages and disadvantages to that, and there's a lot of controversy around that. But any thoughts or experiences or recommendations that you'd like to share with the audience about the issues that we run into when doing clinical trials outside the US?

Jon Speer: Yeah, Mike, I think the interesting... And we've hinted at it a couple of times in this conversation already, but I think the interesting twist here, is that there's this perception in some cases that I can get clinical experience outside the US faster than I can in the US. And to go that next level deeper there's this perception that if I go the path of a significant risk study in the US that's going to require that I do an investigational device exemption, or IDE, and I'm gonna have to submit a packet to FDA and I'm gonna have to more or less get FDA's blessing before I do this clinical investigation.

Jon Speer: So, in other parts of the world, the regulatory nature may be not as stringent. I might be able to just build some prototypes on my bench and do some basic safety testing and I can go to Sub-Saharan Africa or... Who knows, other parts of the world where there are less regulatory hurdles and I can get that clinical investigation faster because that's what I'm after, I'm trying to demonstrate this product works. And your point that you just made a moment ago about, "Hey if I make this product and I use this on a family member, or a loved one, or myself, would I be comfortable with that?" And I think this is an important question, it doesn't matter who in the world is the recipient of my product, I still need to be answering that same question with confidence. But interestingly, I think a lot of med device companies are going outside the US for these studies, because there's the perception that it's faster, that it's easier, that they can gather data and information that they need about the use of their products in a clinical fashion, without having to go through that FDA hurdle. It raises some flags with me sometimes.

Mike Drues: Well, it certainly can, Jon, and it's kind of interesting because the last question that we talked about in terms of design controls, I gave a higher level, more sort of a philosophical response. So for this last question that we're discussing today about clinical trials outside the US, let me get very, very practical, very brass tacks, with my response. The fundamental question that it comes down to is why are we doing this study? In other words are we planning on giving this information to the FDA or not. There are some situations I've been involved in, I'm sure you have as well, where we have, for example, a dozen or maybe more different potential medical device designs, and we need to whittle down that universe, because we can't possibly pursue all of them so we want some real quick and dirty human testing to determine which of these prototype designs are worth pursuing. In that particular case, that data would never, in a million years, be reported to FDA or anybody else. We're just using it for our own developmental purposes.

Jon Speer: Let me pause you there for a moment. Even in that scenario, Mike, we would still... Every candidate that we would go and pursue as far as different options, we would still have information to demonstrate that the product's safe.

Mike Drues: Yes, yes, thank you for interjecting that, Jon, because I should add, this is not an excuse to be sloppy engineers or take short cuts, it's certainly not an excuse to treat people as guinea pigs regardless in where the world they might be living, but I'm just simply acknowledging a reality in this world that unfortunately some folks, including both in this industry, and as well as at the FDA, don't want to acknowledge that happens or pretends that it doesn't.

Mike Drues: So, that's one scenario where we're doing it for our own reasons we're not gonna submit it to FDA, or any other regulatory authority. The other reason is, where we do want to submit that data to the FDA. And so now let me be... Now, let me get very US focused here. So if a company is planning on doing a clinical trial outside the United States and using that data as part of a US submission. Now, you need to be very careful. Now, you need to make sure that you're dotting all your Is that you're crossing all your Ts, that you're following the good clinical practices, or GCPs, that you're using clinical monitors. Because at the end of the day... Well, let me say it this way. So historically FDA has not been keen on taking data, clinical data, for... That has been collected from outside the US, as part of a US submission. However, that has been changing over the years. And now, more recently, I know of a couple of devices that have been approved here in the United States where 100% of the data has been collected outside the US. In other words, there was no US data whatsoever.

Mike Drues: That's still, to a certain extent, the exception rather than the rule, but it is a growing trend, from outside the US. But like most guidances in my opinion, there's really nothing new there. It's all pretty much common sense. You need to work with the FDA in advance. And by the way, going back to the pre-sub, I would also mention in the pre-sub, I would say to the FDA, I would not ask them, I would say it to them. "Oh, by the way, we're doing this particular clinical trial, it's an NSR device, so we do not have to tell you but we're letting you know anyway, and we're planning on doing it in these particular countries and here is our protocol, here is our design, our end points, our inclusion/exclusion criteria, and so on and so on." At the end of the day, Jon, as we've talked about before, we wanna work together with the agency. We don't wanna treat them as our advisory.

Jon Speer: I guess a good way to sum that up is going outside the US. Maybe... There may be a good reason to do so, but it's not a substitute for good science, it's not a substitute for avoiding FDA or following good clinical practices, good design controls and things of that nature. So Mike I know we're just really getting into this topic, perhaps it's one of those areas that we can dive deeper into today, or at another time, I guess, we're out of time today. But it's great for the audience to understand significant risk versus nonsignificant risk. Yes, we will provide some of the guidance documents that exist on that topic as well as when you plan to do investigation outside of the United States, what that FDA would expect and require in those situations. We'll provide all of that information in the text that accompanies this podcast. But Mike I wanna thank you for, once again, diving into... Deep into the regulatory details of topics that are important to the medical device industry. So thank you for your insights today.

Mike Drues: Well thanks, Jon, as always, for the opportunity to chat with you. I enjoy our conversations as well and to help your audience. Both Jon and I have a tremendous amount of experience. I won't add up the numbers between us, [laughter] but we've both been playing this game for a very long time, and I'm sure that if your audience members contacts either one of us, we would be more than happy to help.

Jon Speer: Absolutely. And Mike Drues, ladies and gentlemen, you can find him just do a quick search, D-R-U-E-S. You'll find him on LinkedIn as well as another... A number of other publications in the med device industry, some wonderful content. We should have checked that out. And as we talked about today, during this nonsignificant risk/significant risk conversation there's still an importance of demonstrating your product is safe before you get to that clinical stage. We talked about risk management, and how important that is to making some key decisions.

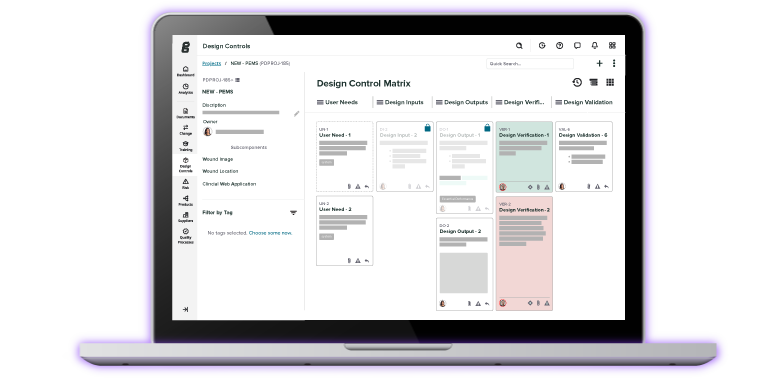

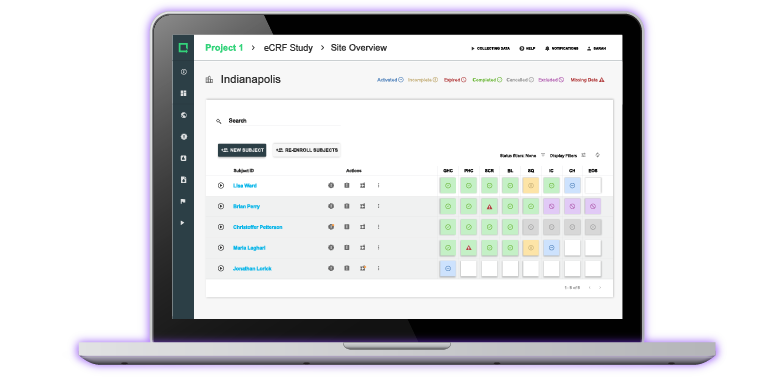

Jon Speer: Folks check out Greenlight.guru, we have a software platform with work flows that are designed to help make design control and risk management practices as easy as possible. Just go to Greenlight.guru request more information, learn more about the product and see if that might be a fit for what you're doing. So, once again this has been Jon Speer, the Founder and VP of Quality and Regulatory at Greenlight.guru and you have been listening to the Global Medical Device Podcast.

About The Global Medical Device Podcast:

![medical_device_podcast]()

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Nick Tippmann is an experienced marketing professional lauded by colleagues, peers, and medical device professionals alike for his strategic contributions to Greenlight Guru from the time of the company’s inception. Previous to Greenlight Guru, he co-founded and led a media and event production company that was later...