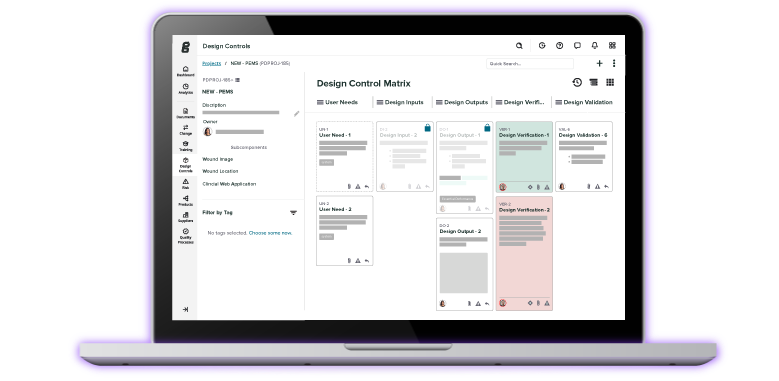

Project Management for Product Development of Medical Devices

How should you approach project management for medical device product development ? Stop managing your projects using methods and tools that delay timelines and increase costs, and start following the proven best practices that save you time and money, and yield optimal product outcomes.

In this episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast, Jon Speer talks to Devon Campbell with Prodct, LLC and Christie Johnson who is also with Prodct, LLC as well as Kasota Engineering about Greenlight Guru Academy’s new course offering, Introduction to Project Management for Product Development of Medical Devices.

LISTEN NOW:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some highlights of this episode include:

- It’s assumed that engineers good at managing projects, getting things done, and working with different resources/team members make good project managers.

- The gold standard is Gantt charts and waterfall methodologies. They have their place and have done a lot of good, but developers do not have to follow the waterfall method - it’s simply a project management practice and example.

- There’s an appropriate time and place for PM practices and tools, including the Gantt chart. However, don’t blindly apply learned principles.

- The wrong time to use a Gantt chart is managing how people do their work. Be vulnerable, open, and trust the professionals to know what they are doing and get their work done.

- Project planning and management are not the same. Project planning does not equal project management.

- Follow the Keep It Simple Stupid (KISS) philosophy. Rather than build complex and sophisticated tools, acknowledge that you won’t do it right the first time and put time in to react to what you learn and optimize.

- Who’s running the show? There’s a lot of overlap and not enough room to redo, learn, and make a product better. Also, a lot of iteration happens between those steps. Give time and respect to making a product stronger.

- Good project management is perpetual because there is a flow to it. It’s cyclical. Prototype and conduct testing early and often if the schedule allows to define and refine product details.

Links:

Introduction to Project Management for Product Development of Medical Devices

Christie Johnson with Kasota Engineering

FDA - Design Control Guidance for Medical Device Manufacturers (Waterfall Diagram)

FDA - Quality System Regulation, Part 820

Waterfall vs. Agile: Battle of the Product Development Methodologies

X-teams: How to Build Teams That Lead, Innovate, and Succeed by Deborah Ancona

The Greenlight Guru True Quality Virtual Summit

MedTech True Quality Stories Podcast

Greenlight Guru YouTube Channel

Memorable quotes from this episode:

“Starting as an engineer and then moving into quality and approaching things with a 30,000-foot view, you kind of see the whole project and the impact of all the sub-tasks. It’s hard not to want to get involved and make sure that everything that needs to get done does.” Christie Johnson

“It will ultimately deliver something. It might deliver it over budget. It might deliver it over time. It might deliver it with a bunch of disgruntled employees who hate going through product development because of the way that the project is being managed.” Devon Campbell

“Potentially, too many bells and whistles that it makes it really easy for you to create something that looks really awesome, but it’s really hot garbage.” Devon Campbell

“Critical path calculations and analyses through tools is generally meaningless. I don’t believe it whenever I see it because we build these really complex and sophisticated models.” Devon Campbell

“There’s a lot of overlap and not enough...room to go back and redo and learn and make the product better. There’s a lot of iteration that happens between those steps.” Christie Johnson

Transcription:

Announcer: Welcome to the Global Medical Device podcast, where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Jon Speer: In my over 23 year career in the medical device industry and counting, I've learned to really enjoy frankly, project management. And I would say early days of project management many, many years ago, maybe not so much, or maybe better stated, I had a lot of misconceived perceptions and thoughts and ideas about what project management was supposed to be for medical device product development. And let's just say, after learning thing or doing things the wrong way, a few times, I learned some better ways. And a lot of the conventional wisdom that's out there with respect to project management and medical device product development, it's just frankly wrong. And this is one of the reasons why we're super excited to have awesome course on medical device project management available to you for purchase in the Greenlight Guru academy. So check that out. We'll include the link to that course in the notes that follow the podcast episode and as a super bonus for you at no charge, joining me on this episode of the Global Medical Device podcast is Devon Campbell with Prodct and Christie Johnson, founder at Kasota Engineering, and also a preferred partner of Prodct. So enjoy this episode of the Global Medical Device podcast, where we talk about project management. Hello, and welcome to the Global Medical Device podcast. This is your host and founder at Greenlight Guru, Jon Speer. And joining me are two of my most favorite people to talk about and based on, or talk not about with. That was-

Devon Campbell: Maybe after today's call, we'll be talking about, we'll see.

Jon Speer: Yeah. Two of my favorite people to talk with and based on the few minutes that we chatted before we hit record, this should be a good one. So joining me is Christie Johnson. Christie is the founder at Kasota Engineering and a partner with Prodct. And speaking of Prodct, we have Devon Campbell, the founder of Prodct joining us as well. So Christie, Devon. Welcome.

Christie Johnson: Thank you.

Devon Campbell: Thanks.

Jon Speer: All right. So topic we're going to dive into today, it's project management and I'll start, and then I'm just sure things will flow from there. So I started my career back in the late nineties as a product development engineer for a medical device company. And frankly, I was pretty good at it. I knew how to manage projects. I knew how to get things done. I knew how to work with the different resources and team members. And I had a lot of success very quickly and very early on in my career. And I didn't realize certainly as it was happening, but at least at the company that I was with and I think this is common in a lot of companies because I was good as a product development engineer, the next drum and a ladder that I got the climb was I got to be project manager. And so there's this assumption, oh, good engineer. You must be a good project manager. I'm going to pause there in case your reaction, see if you've had similar sorts of experiences or heard similar sorts of things.

Devon Campbell: I think that journey is not an unusual one for good development folks.

Jon Speer: Yeah. Christie, what about you? Did you follow that same path early on in your career?

Christie Johnson: Yeah, it was hard for me to, honestly, because starting as an engineer and then moving into quality and approaching things with a 30,000 foot view, you kind of see the whole project and the impact of all the subtasks on a whole project. And it's hard not to want to get involved and make sure that everything that needs to get done does.

Jon Speer: Yeah. Frankly, I think I gravitated toward more project management. Arguably speaking, I'm probably a better project manager than an engineer when it comes down to... I know enough about engineering, but I think that's also part of the engineering discipline is just getting things done. And I think that's why I was successful in project management as well, because I just got things done. But I remember those early days of being a project manager, I was consuming all of these books like critical chain, the Eliyahu Goldratt book on the theory of constraints. And I would read books on Gantt charts and I would go to project management courses and all this sort of thing. And guilty early on a project manager role would prepare a Gantt chart with like 350 line items, try to create all these predecessors and dependencies and all that. And I remember the first time I did this, I was like, man, this is amazing. Right? And then you go talk to people and try to understand where are we? What's going on? All I was doing was chasing my tail because now I fell into this, I think a trap, where I was just managing by this thing called a Gantt chart. And all, all I would do almost every day was updating task and dependencies. And the moment that I updated something, it was instantly wrong. So why do we fall into this trap?

Christie Johnson: Why do we lose a little bit of our soul every time we updated 250 line Gantt chart?

Jon Speer: Yeah. Right. Why is this practice perpetuated in our industry as like the gold standard? Because it is not.

Devon Campbell: Yeah. It's not. I think so a lot of that flows from waterfall methodologies. Right? They have their place. They've done a lot of good. A lot of folks in our industry feel like we have to do waterfall. I think you and I might have talked about this in the past, Jon either casually or on a recorded call, but the FDA 21 CFR 820, they're kind of going through and the guidance for it. They give some examples of project management and they kind of show that very classic waterfall diagram. You know which one I'm talking about with little rectangles is kind of black and white and gray scale.

Jon Speer: Oh yeah.

Devon Campbell: And they go in a little line and a little bit of flow down. And I don't know, a lot of times people say, well, that's... FDA says we have to do waterfall. And so they just do it, which is baloney. They don't say you have to do waterfall. It is an example. If you read the language closely and with precision, it does not mean that you have to follow that. But it's a brute force in elegant way. As we said before this call, I'm not going to hold my tongue regarding my thoughts on a lot of PM practices. But I do feel like building those Gantt charts, if you can follow it, if you can maintain it, if you can somehow magically keep it going then great. It will ultimately deliver something. It might deliver it over budget. It might deliver it over time. It might deliver it with a bunch of disgruntled employees who hate going through product development because of the way that the project is being managed.

Christie Johnson: I almost got hired once for not complying with the management requirement to keep my 250 line Gantt chart updated, multiple a week.

Devon Campbell: Yeah. Don't get me started on manual schedule updating. It should be an automatic thing. So I don't know. I think it's just like a self- fulfilling prophecy. I think a lot of people just go with what they know and they read these books and they see all these things on how to prepare projects like that. And don't get me wrong. We'll say from the start, I feel like there's an appropriate time and place for all of those sorts of tools. What really gets me angry and kind of ruffles up my feathers about things is blindly applying those principles that you learn and just come in and say, okay, well I'm project manager. I just learned a bunch of stuff. Exactly what you did, Jon.

Jon Speer: Yep.

Devon Campbell: As the product development guy, as a product development engineer, I hated you for coming into my cube and saying, Hey, where are we on this part of the device? Where are we on this aspect of the medical device? And then I see you again the next day, where I see you that same afternoon asking me exactly what you were saying, the spiral of death that you kind of fell into chasing your tail and I'm just going to start feeding you garbage because I'm so tired of seeing you all the time.

Jon Speer: My favorite is when you ask somebody like, I'll say, Hey Christie, we need some CAD for this particular product. How long do you think that's going to take you? And you're going to just like make a wild guess. You're going to say three days and you have already put in your head some sort of buffer. You may or may not have factored in all the other things are going on in your world. But purely just made up some gas as far as how much that's going to take. And so me as project manager like, all right, she said three days, we better add in this other buffer of five days and I need to have this done before that's done. And it's just when you have a Gantt chart, that's got that level of granularity and specificity, it's not precise. It's not accurate first and foremost and that's all you're doing. And you're just becoming the annoying guy in the office, that's asking stupid questions that really doesn't have a grasp of what's really going on. That's who you start to become if you're not careful.

Christie Johnson: And then you get garbage back from your people too. I'm just going to spew an answer at you to get you off my back, when like you said, you don't know if it will really take me 10 minutes and I built in three days or if it'll take three days and you need to build an extra time, so you're getting garbage too.

Jon Speer: Or my favorite is it takes you three calendar days, but it actually only takes you four hours of time. And so I've got to figure out how to work my Gantt chart magic to build that in. And it's just like time out. There's got to be a better way. There just has to be a better way. So, and I think it's complicated because obviously the regulations state thou shall do project planning. And I think there's this approximation, that project plan and project management are synonymous. And I think what a lot of people hear or interpret is that, oh, that means I have to have a schedule and a timeline for my project. And that's not really good project management or planning in my opinion. What do you think?

Devon Campbell: I think that's a great observation, Jon.

Jon Speer: Yeah.

Devon Campbell: That project planning does not equal project management.

Jon Speer: Yeah. So Devon, I know you've got a whole list and library of materials that you're going to share, but I guess let's give some people some of hope there is a better way. And for folks listening, if you're dealing with project management, you're listening to three people that have managed dozens and dozens of projects. Confess I've done it the wrong way a lot of times, but I've done it pretty well a lot of times as well. So we've got a lot of experience here. So this should be a good list of tips, pointers, and suggestions. So Devon give us some alternative voice to think.

Devon Campbell: Before I rock the boat too much, let's dwell a little bit in what everyone does know in like Gantt charts and critical path analyses and PERT and all that kind of acronyms that people learn in project management courses. I think what's really important is that you evaluate and you use the right tool at the right time. There's absolutely, and I've managed huge project with multi- billion dollar market cap diagnostic players. I've managed really big project and I definitely have used Gantt charts, but that Gantt chart would have a very, the further out that I'm looking, the more course the resolution gets, right? So if I'm looking really far out, I might be looking out by quarter. Maybe even by half you say, generally, we're going to do this. Then we're going to do this. Then we're going to do this. And also depends on who you're talking to audience wise. If is the executive team, the rest of your peers on the leadership side, you keep it kind of course. And there it's appropriate to say these things flow into these things. We can't do validation until we've actually gone through and done verification, things like that. There's some natural pieces to it.

Jon Speer: Sure.

Devon Campbell: But I would say that the wrong time to use a Gantt chart and to try to calculate a critical path and all of that stuff is in managing how people do their work. I think it's important that we say, all right, you are development professionals, you're development engineers and scientists and chemists. You know what you're doing, we should trust them a little bit and let them do their work, how it best suits them, not based on how the Gantt chart tells you, you have to do it. So from that perspective, I liked to use Gantt charts, high level. And then if you wanted me to give you kind of like, okay, well what's going on in the next couple months? I would only look out two months. I would never look beyond two months and we all know why. Everything's crazy within two months.

Jon Speer: Yeah.

Devon Campbell: So, okay. I'm going to schedule two months out and I'm going to schedule at one week, maybe one week, definitely two week increments, but no finer than that. And then when it gets to the point to say, okay, after those two weeks, or maybe after the four week, which is two, two week periods, it sounds a lot like agile.

Jon Speer: Sound a little bit like scrums here. Let's yeah.

Devon Campbell: Well, it's a good cue for anyone listening to go back to our earlier conversation. I forget which episode it was where we did waterfall versus agile methodologies.

Jon Speer: Yeah.

Devon Campbell: And kind of dove into that.

Jon Speer: Yeah.

Devon Campbell: But I wouldn't go any deeper than that because I trusted my teams. I said, look, I need you to deliver this in two weeks or this four week increment, I need you to deliver that. You guys organize yourselves. I don't care if you're going to use a Gantt chart. I don't care if you're going to use Microsoft project or team Gantt or Excel. I don't care if you're using napkins from the cafeteria. Somehow organize yourselves that makes the most sense for you and get your job done.

Jon Speer: Yeah.

Devon Campbell: And you keep delivering on that, I'm going to stay out of your hair. If you don't, then we're going to have to intervene a little bit and I'm going to have to send younger PM Jon in to like ride on you and make sure that you're getting everything done.

Jon Speer: So is it-

Devon Campbell: Just the threat of that was enough to get people to do it. But it was liberating to be able to say, oh great. Someone trusts me to do my job. I'm going to do it.

Jon Speer: Yeah. So I don't know if this is over simplifying or even accurate, but what I'm hearing you say is know where you want to go. You and I have talked about this a lot anyway, know where you want to go. And let's say in the next two weeks or four weeks, or a relatively finite window of time, know where you want to be by that period of time and let the teams have autonomy to figure it out. Or the people have autonomy to figure it out. So it's almost like managing by milestone more than it is anything else.

Devon Campbell: Yeah. And it's allowing yourself as a leader to be vulnerable and to be open, to trusting your team and well, having someone breathe down your back and say, well, what exactly are they doing this week? And you're like, I don't know, but I trust my team. I know they've delivered the last two months. I know they're going to keep delivering right now.

Jon Speer: Yeah. And then that puts the onus and responsibility on me or management to make sure priorities are clearly defined anda articulate. If we're pulling from the same resource pool to manage five or 10 projects, they better know with crystal clarity, which ones are the top priority. Yeah.

Devon Campbell: Christie, I know you have laundry list of notes and things too. Have we hit on any of your buttons yet when it comes to project management?

Christie Johnson: I think taking a view of a month or two months out as kind of like a max for what you're going to try and manage or help your team manage, helps take just some of the pitfalls out of like the long term vision. So for example, maybe if you are talking with your engineering team and you need them to help solve some kind of technology problem in the next four weeks, one pitfall that I've seen happen that is kind of an encouragement that could come from project management is don't just singular path your solution. To get it done in these two to four weeks, let's try two or maybe even three parallel path, figure out one of them might stick maybe two of them, and then you'll have the option to take the cheaper or easier one. But I think that's like an example of just when you set that two or four or six or eight week goal for the team, just helping them think through how are they actually going to achieve. When challenges do come up, how are they actually going to achieve that?

Devon Campbell: Yeah, that's a really good point. As both of you were sharing, I also remembered an earlier version of Jon, a lot of the projects that I would manage more times than not, almost every time actually, the moment that I would start the project, my boss would give me the due date and say, oh, it needs to be launched by October the 12th, because that's when we're unveiling this product at the American society of anesthesiologist or whatever the case may be. So the due date was given to me before we even started the project. So I think that's what forced some bad habits on my part is like, okay, I took the date of October 12th and let's just say for conversation, that's 2022. I would work backwards, reverse engineering if you will, the timeline and figure out, okay, well how much do each of these things have to take in order for us to make that achievable? And I think that drove a lot of the bad habits on my part is just accepting that as gospel and then working backwards to make it happen. And then unfortunately applying annoying pressure on people and micromanaging once upon a time. And I just, fortunately I had people that were tolerant and they're like, it all worked out, but I think that's what drove a lot of bad behavior too, is that we were so held on the end date and being absolute and everything's going to go perfectly well. And it's not. It's just not when product develop-

Jon Speer: Right.

Christie Johnson: And I think it also assumes too that your direction is not going to pivot. So there's good pivots and bad pivots, right? There's new opportunities that it come up that as a company, you evaluate the opportunity and you think, oh, this is a new market. COVID opened up a huge market for all kinds of products to pivot into, that would not have gone there without the pandemic. And sometimes that's an okay thing, but that's going to impact what the original project resources would've allowed to hit the original finish line whether the finish line is a product launch or an FDA submission or whatever that is. So I see that all the time. Investors with sweet nothing's ideas into the ears of whoever will listen at the team, the executive team, and Hey, this is a great idea. This is a new market. You could take your technology to, and then they want your finite engineering team to be able to pivot, yet still will meet their original deadlines. And how do you come to terms with that?

Devon Campbell: Yeah, absolutely.

Jon Speer: Yeah. So what do we do? What are, as you both know, I always like to try to leave the audience with some practical advice, tips and pointers, anything come to mind. Let's imagine that somebody listening might be, one of these engineers, that's climbing the ladder and realize, oh wow, they've graduated from being an engineer. Now they get to be a project manager or maybe someone listening is with the startup and they've got this critical date that they're trying to hit and all they know is, you know, the conventional wisdom on project management. So they go in and start to concoct their 300 line item, Gantt chart. How do we stop the madness?

Devon Campbell: Well, that's a good one. If they're doing some work and they find themselves with a 300 line Gantt chart, you've done something wrong. It's time to stop and take a step back and give yourself some freedom and the flexibility to manage a little bit better granularity, less granular schedule because 300 is just unsustainable. It's not scalable and it's going to be out date before you even hit save on the first version.

Jon Speer: To interrupt you on that, going back to the point that you made a little bit ago, that you like to be granular in a two to four week window or so because it's close, as far as time is concerned. You should have enough information to have a fair amount of granularity now. Four months from now, forget it. But do you find that you change the tool that you're using for those different windows? Or how do you do that? I don't know if my question was very clear but...

Devon Campbell: Let's just explore, you can absolutely use Gantt charts and project. I would recommend people have the courage to explore if you're going to use Gantt charts, to use other Gantt charting and road mapping software.

Jon Speer: For sure.

Devon Campbell: There are some really well known big ones out there that everyone feels is the industry standard. But I would argue that they have potentially too many bells and whistles that it makes it really easy for you to create something that looks really awesome, but it's really hot garbage. And you don't know any better because you have this really beautiful giant schedule with start to finish, finish, finish, start, start, delayed start, all these different things built into it. It's too sophisticated. And I'd rather the attention to detail be put into the product development process, not into managing the schedule. So there are other tools out there that do Gantt is all I'm saying, and people should have the courage to play with them and try them. There's a whole bunch of really great web- based ones out there that people can toy with.

Jon Speer: Well, a couple thoughts too and reactions. I think a lot of project managers make the mistake that just because they sort of kind of understand the project management tool that they use, a Gantt or whatever the case may be and they know what all the task is and what the predecessor is. And when the start date is and all these sorts of things and they hand it to people and I think they make a false assumption that everyone getting this, number one reads it and number two even knows what it even is trying to communicate. So I think that's a mistake that a lot of people make.

Devon Campbell: Yeah. I'd also be careful with how many, you mentioned predecessors, how many predecessors do you link to something? Because what ultimately happens is you look at one and you'll see there's like 15 different predecessors, right? There's just a ton of things because someone got a little overzealous with, well, I can't do this until that's done. I can't do this until that's done. I can't do this until that's done. And Christie and Jon, they both have delivered these things to me before I can do my job. And now you have way too many predecesors and it's one of the reasons why I tend to say critical path calculations and analysis through tools is generally meaningless. And I don't believe it whenever I see it because we build these really complex and sophisticated models, kind of follow the kiss philosophy, keep it simple, stupid. And if you're going to use Gantt, just keep it really simple. It doesn't have to be that complicated, but when you're doing so, and we talked about this a little before in the call, I think it's really important to recognize, especially in medical device industry, there's a natural and very healthy cyclical nature to what we do. You don't just develop the product, you're good. You got it right the very first time. It's like, we're just stamping out implants and in vitro diagnostic devices and softwares medical device things, you don't just stamp them all. And it's exactly the same. You have to kind of think through them carefully. And we know, we go through these processes, we learn from it, we optimize the design, we go back into it. It's very cyclical. And those tools by their very nature, don't really account for the cyclical nature of what we do. So at least try to throw in a couple, acknowledge that what we do, you won't do it right the first time and throw in some opportunities to learn. And if you do, you put in like an early alpha test or a beta test, or even some product verification, put some time in afterwards to react to what you've learned.

Jon Speer: Hundred percent.

Devon Campbell: Right. It always goes design freeze, verification goes straight into validation, goes straight into FDA. Wow. So you're presuming everything works perfectly as soon as you hit design freeze. No work is done, right? Let the engineers and the scientists work on a new project from here on out. That's not how it works. And we all know that that's reality.

Jon Speer: Christie, that's kind of what you were talking about earlier. I think we do. We get like blinders on, We're like, all right, we're going to follow this path. To your point, we don't take intentional pauses to learn and there will be pivots. There will be absolutely 100% something will happen in your project. I don't care how perfectly ran it is. In fact if something didn't happen-

Devon Campbell: Something's wrong.

Jon Speer: Yeah. Then I'm it's wrong. But I think a lot of people just say, blindly, they go down this path like, oh, we don't have time for that. We got to move on the verification bill, blah, blah, and so on and so forth. So any thoughts, Christie?

Christie Johnson: Yeah. I think that's stage two that you're talking about, Devon is one that I see a lot of companies struggle with, especially that work with contract manufacturing, organizations for engineering, and then transfer to manufacturing. So you have design engineers finishing up the design, documenting the design, going into verification testing, which eventually goes into validation testing. They're writing protocols, they're testing, they're learning, they're pivoting, they're changing the design, updating it, testing it again, changing the test methods. Reving the protocols, testing again, gathering data, analyzing the data. Small CMOs will also have those same engineers writing the work instructions to transfer the design into manufacturing and sourcing suppliers to provide parts to that manufacturing process because parts tooling takes time to spool up and you've got to qualify the parts when they come in and got to qualify the processes and set up testing for your processes. And I think a problem that I've seen in project management with an organization like that is that they use the same resources to do all those things and the engineers show up and they're like, who's running the show? You're trying to schedule my time and schedule this project. You set this random date for a product delivery and we're not done with verification testing. We're not done with the work instructions. We don't have all the parts in. We've got to sleep sometime. And I think there's a lot of overlap and not enough, like you're talking about room to go back and redo and learn and make the product better. And there's a lot of iteration that happens between those steps and the waterfall verification to design transfer. Design transfer can take a while and it can be messy. And if you give it a little bit of respect, give it a little bit of time. That's when you really make your product stronger, I think.

Jon Speer: Yeah, but this is the one thing that's, it can be troubling, I think. Let's imagine that I am a startup company or any company for that matter. New product development is a lifeblood. It is a fuel to an organization. And if I don't have good project management and we can talk more about what good project management means, but how in the world will I know when anything's going to be done, if I'm only looking at these two or four week slices of time? I know we have this thing we need to bring to market. How in the world can I present a forecast or how can I let our investors know? Or how can I prepare our contract manufacturing organization, if I'm not looking at it in a bigger picture, I'm only looking at any small sizes. Any thoughts?

Devon Campbell: Well, just the tip with your contract manufacturing organization, they should be pulled in super early and be part of the development process. If they're part of the process, instead of the end point of the process, I guarantee the transfer will go much smoother and you'll be better informed as to what it actually takes to move it there. But to answer your question, Jon, I think it really comes down to making sure that right... You like to use this word a lot. Right? Right sizing your project management tools for what you're trying to do. So you're looking out of 3, 4 year product development process. That's fine. You could look out that far or even a roadmap to see, okay, we're going to release these different changes to the software over the next 36 months. Okay, good. That's fine. We have a high level there. Now we go down a little bit lower. How are we going to generally get that this timeframe is going to be, could look waterfall- ish. This timeframe, we're going to do verification validation. So we can do resource planning. This time frame we're doing, we're in raw just development. So we can do resource planning. But when it gets down to the nitty gritty and the day to day work for the folks that are doing the business of product development, that's what I always just found to get out of the way. And you say, well, wait a second. How do I know it's going to get done? If you create the right culture and the right environment where your teams can flourish and feel respected for their contributions and feel trusted, they're going to deliver. As they continuously deliver, you can look back and say, Jon you're questioning my approaches. That's fine. Take a look at my history so far. Knocked it out of the park, knocked it out of the park. We didn't on this one. That's okay. We adapted, we learned from it. We came back. We did it better the next time, knocked it out of the park. So every time we're doing these two planning sessions, we're doing a pretty good job delivering on our two week increments within that two month planning session. And a couple times we don't and that's natural. That's going to happen. And we adapt from it. But to be able to look back and say, here's the proof's in the pudding and we've been doing it.

Jon Speer: Yeah.

Devon Campbell: It doesn't take too long before people start saying, okay, I just need to get out of the way and let the product development juggernaut do its thing. And let us go. And we do it.

Jon Speer: Well in what you just said, there's a nugget in there that I want to extract a little bit more explicitly to those listening. Good project management is perpetual and there's a flow to it. We said this a moment ago, it's cyclical and we're going to be cyclical in managing our project because every few months, or couple weeks, depending on that granularity, whatever cycle we're in, we're going to do a deep dive session or two or maybe more where we're going to be, that's all we're going to be working on for a period of time is the next wave, if you will, of activities in this project. So we're going to be planning with a lot of granularity, a lot of specificity. Then we're going to dive into that next chunk of work and we're going to let the team be autonomous, respect their expertise and their skills and let them do the work. And then we're going to do it again. So, it kind of rinse, repeat, rinse, repeat, rinse, repeat it. But I want people to hear that because a lot of times when it comes to project management, it's done with a lot of precision and granularity or intended precision and granularity on the front end from beginning to end of project. And then it's hardly ever revisited and revamped and retooled along the way. So...

Devon Campbell: And you have to be humble enough to stop and take a look at yourself, right?

Jon Speer: Yeah.

Devon Campbell: And say, how are we doing? How can we do better? Exactly.

Jon Speer: Well, I know we're getting toward the tail end of this particular conversation, Christie, any final thoughts on project management that you want to leave the listeners with?

Christie Johnson: I think one of my favorite tips when planning out testing, especially if it's like big, expensive testing in a lab, do a non GLP study first. Do benchtop studies first, de- risk your testing process or your test itself, and then give your team a chance to pivot and learn from that and make any changes and then set yourself up for success when you actually execute the testing that you want to take credit for down the line. Instead of failing, like at the end of the project, that's really painful.

Jon Speer: I'm so glad you shared that. Because to me, what I hear you say is that encourages me to prototype early and often, to do informal tests early and often. And I think people don't do this enough. And I think that is like, it is part of the-

Devon Campbell: Sometimes the schedule given to them doesn't allow them to.

Jon Speer: True. And maybe that's part of the challenge, but prototyping and testing, these are all ways that are going to refine your product. It's going to help you define the details about your product. So I like that suggestion-

Christie Johnson: In the meantime, we're not in the waterfall block for verification unit.

Jon Speer: Those people who wait to do verification going into verification blind, man, that is a brave activity. Good for you. And I'm sorry about outcome because you're going to have to make some tough decisions.

Devon Campbell: Never do that.

Jon Speer: Yeah. Don't ever do that. All right. Devon, any final thoughts on project management?

Devon Campbell: Yeah. I'll leave you with kind of two reading assignments for anyone that's interested in learning a little bit more. The whole idea of kind of trusting your team and taking it to a certain level, but then letting them do their thing without intervention, letting them do it. A lot of that, I was in a class at MIT many years ago, back in 2010, I guess. And Deborah Ancona has this idea called X teams. And in this book, X teams, she introduces this concept of distributed leadership where you kind of create little boundaries around teams and say, you do whatever the hell you want to inside the boundary. You know what you have to deliver and when. I don't do care how you do it. You guys self organize. And it was a highly influential book for me, 11 years ago on how to feel comfortable trusting my teams to get their work done. So we talked a little bit about that in a number of my comments and I want to tease out one extra tool. A different way that people can kind of look at structuring projects, that's not Gantt at all. In fact, it completely rebukes Gantt and everything else, but there is Dr. Eppinger at MIT. I took a class from him, actually a couple classes from him. He introduced me this concept of design structure matrices. And if, instead of focusing on the deliverables being items, I can't do my verification testing until I have the unit to do verification testing on. That's a very natural progression and easy way for us to wrap our brains around product development. Forget that. You kind of throw all of that away and you focus only on the information that needs to be transferred from one person to another or from one group another like what information do you need before you can start the verification aspect? Well, you don't have to have the entire design done. You need certain pieces of information that you can start writing your verification protocols ahead of time. So if you focus on information, not on deliverables themselves, but information that you pass from one party to another, there's a way in a DSM framework that you can visualize all the information flow, including all the information you need to do different steps of an entire Gantt chart you could do in DSM instead. But within DSM you can run optimization algorithms to say, okay, this piece of information Christie's going to generate and Jon needs it here, but there's really no reason why she can't generate it here and Jon can get it here. And now Jon can actually start doing his job way earlier than what was planned out on the waterfall chart.

Jon Speer: Yeah.

Devon Campbell: And it blew my mind, which is why I kept taking classes with Dr. Eppinger, so I could keep learning more about DSM, but the idea that mental pivot of moving away from things and moving to ideas and information was incredible. And I suggest anyone listening, go take a little look at it and learn from it if they're interested.

Jon Speer: Yeah. Devon, if you could share a link or, or an article or something like that, I'd be happy to include that-

Devon Campbell: Yep.

Jon Speer: ...in the notes that accompany on the show. And I like your information piece too, because I think that's one of the things that I eventually figured out as a young project manager is I think I would say the most important, at least from my lens thing about project management is communication because that's where all projects break down is poor communication. And maybe to your point, Devon, lack of information. I think communication with information, but also knowledge and empowerment for your team is really important. I learned that when I taught people that were going to be working with me on a project, especially folks that maybe might have been in manufacturing resources. But the moment that I taught them a little bit about what the product was, what problem we were trying to solve, how we were trying to get there, what we were trying to achieve, what their contribution, how that was making a difference. I think once people learned about that, they got a little bit of knowledge and information, shared with them about what we were trying to do, it changes the dynamic as well. And I think it improved the culture from a project perspective.

Devon Campbell: Yeah. What you're sharing there is a really important distinction kind of between project management and program management.

Jon Speer: Yeah.

Devon Campbell: Right. But it doesn't mean that because that's pretty common in program management to make sure everybody understands. We work in the medical device industry. We do really cool stuff and we help a lot of people.

Jon Speer: Yeah.

Devon Campbell: And to make sure that you make that obvious and clear to the rest of the team is important. There's no reason why that passion shouldn't bleed into project management as well.

Jon Speer: Absolutely. Well, Devon, Christie, thank you so much. I appreciate you sharing some thoughts and insights. It just reminds me that we could do a other podcast episodes on variations of this topic are probably a half dozen or more other topics. So we'll compare notes after today's session and see if we can find another time to chat. Folks, Christie Johnson, Devon Campbell, Prodct. You can learn more about product website, P- R- O- D- C- T. D- E- V. so check that out. And certainly I guess, as we're wrapping things up Devon, Christie, what does Prodct do and why should people care?

Devon Campbell: What does Prodct do and why should people care?

Jon Speer: Yeah.

Devon Campbell: I'll take a stab Christie and you correct me. We are kind of a collection of resources. We focus on helping emerging entrepreneurs in early stage startups in medical device, med tech, biotech, therapeutic spaces. But we're very succinctly focused on those earlier stage companies, not the big ones. Between all of us involved in the project, we have a lot of success in our background. We have a lot of exits and we have a lot of hashing to share what helped us have those successes with really exciting, fun, new projects and cool people that are poised to be able to make a big difference. And we want to be able to be a part in helping them put together the infrastructure that they need to be able to get there because product development is messy, as Christie said earlier, but product development in a highly regulated space like ours and medical devices, it's messy and can be a little scary and can be intimidating. And we like to help people kind of chart their path through that and coach and mentor and mold them through it. And we've been pretty successful with it.

Christie Johnson: We like to meet people where they are and let them come to us as they are. And it doesn't matter if you have a background in what you're doing, we can probably teach and quote you using our experience and our collective experts that we pull in.

Jon Speer: Yeah. All right. And what Christie and Devon are also, I'm guessing, thinking as well. There's no reason why medical device product development shouldn't be fun and exciting.

Devon Campbell: Absolutely.

Jon Speer: So this is a large part of what product brings to you and your teams, just fun and excitement. Who would've thought medical device, project management and product development is fun and exciting? I know that Devon and Christie have a good time. I am a little jealous of them from time to time as they both are full ware. But anyway, I digress. Thank you all for listening to the Global Medical Device podcast. As you know, we have the only medical device success platform designed specifically and exclusively for the medical device industry by actual medical device professionals. Did you know that Greenlight Guru also has the Greenlight Guru academy? That's right. We are offering courses to you on a variety of topics from design control to risk management, to CAPAs and so on and so forth. Oh, and guess what? We have a course on project management. We've partnered with medical device HQ and are offering their project management course. So be sure to check that out, we'll include a link to that course in the show notes as well. So thank you for being loyal listeners of the Global Medical Device podcast as always. This is your host and founder at Greenlight Guru, Jon Speer. Thank you.

ABOUT THE GLOBAL MEDICAL DEVICE PODCAST:

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Nick Tippmann is an experienced marketing professional lauded by colleagues, peers, and medical device professionals alike for his strategic contributions to Greenlight Guru from the time of the company’s inception. Previous to Greenlight Guru, he co-founded and led a media and event production company that was later...