Preparing Your Pre-Submission with the Content FDA Wants to See

.png?width=2400&height=1200&name=GMDP-header-Mike%20Drues%20(1).png)

A Pre-submission can add tremendous value with the feedback given by FDA, which manufacturers can use to guide product development and marketing submission planning.

There is an art to preparing a Pre-submission, though, so it's important to include the necessary contents (and avoid common pitfalls) that will yield the best possible results.

In this episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast, Jon Speer talks to Mike Drues from Vascular Sciences about Pre-submissions. Listen as the two share recommendations about what content to include in a Pre-sub request to FDA as well as costly pitfalls to avoid with this particular Q-submission type.

LISTEN NOW:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some highlights of this episode include:

- A Pre-submission meeting is an opportunity to communicate with FDA prior to a marketing submission.

- About 3,306 medical device-related Pre-submission requests were made to FDA in 2020. In 2021, more than 1,500 Pre-submission requests have been made so far.

- Not all Pre-submission requests are made for meetings with FDA. About two-thirds of Pre-subs requested a meeting and one-third requested written email communication only.

- On average, FDA takes two months to give a written response of approval or denial for a Pre-submission request.

- A Pre-submission is completely optional and never required, but highly recommended.

- The only time that Mike does not recommend a Pre-sub is when the marketing submission is a ‘slam dunk’ in terms of the agency's decision. That rarely seems to occur, especially because 75% of 510(k)s and 89% of PMAs are rejected the first time.

- Unlike 510(k) and PMA submissions, as well as 513(g) requests for information, there is no user fee associated with Pre-submissions.

- When crafting a Pre-submission, justify reasons for why certain approaches are being taken over others.

Links:

FDA - Q-Submission Guidance - Requests for Feedback and Meetings for Medical Device Submissions: The Q-Submission Program

FDA - Premarket Notification 510(k)

FDA - Premarket Approval (PMA)

FDA - 513(g) Requests for Information

FDA - Medical Device User Fee Amendments (MDUFA) Reports

FDA - Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH)

The Greenlight Guru True Quality Virtual Summit

MedTech True Quality Stories Podcast

Greenlight Guru YouTube Channel

Memorable quotes from Mike Drues:

“A Pre-submission meeting is an opportunity to talk to the FDA before you actually make your submission.”

“Clearly, the popularity of the program is increasing.”

“A Pre-sub is purely optional. It is never required. A company can choose to do a Pre-sub or not.”

“Unlike 510(k) and PMA submissions, unlike 513(g) requests, and so on, there is no user fee associated with the Pre-sub—although at least not yet.”

Transcription:

Announcer: Welcome to the Global Medical Device podcast, where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Jon Speer: I just had a chance to talk with Mike Drews from Vascular Sciences, familiar voice and face on the Global Medical Device podcast. On this episode, we talked about pre-submission. Yeah. If you've listened to Mike and I chat before we often mentioned the benefits of pre- sub and how they can be super helpful and add value to your medical device products journey to get to market. We get into a little bit more depth and detail as to the contents of a pre-submission on this episode, and one of my favorite things that Mike shared comes at the end. The whole thing's meaningful and worthwhile, but at the end, he shares the key thing that he does when crafting a pre-submission and I wrote it down. So bear with me, is he justifies why the company is doing their particular thing and taking their particular approach, which, that makes great sense. He also justifies why they are not doing something else. To summarize that, here's why we're doing X and here's why we are not doing Y. Really great advice, but I hope you enjoy this episode of the Global Medical Device podcast. Hello, and welcome to the Global Medical Device podcast. This is your host and founder at Greenlight guru, Jon Speer. Joining me today is familiar voice, and now becoming a familiar face with Global Medical Device podcast listeners is Mike Drews with Vascular Sciences. Mike, welcome.

Mike Drews: Thank you, Jon. Always a pleasure to speak with you and your audience.

Jon Speer: For sure, and I thought generally after we have our podcasts, I'll give people a little bit of a glimpse into some of the inside baseball that you and I have, but we always talk about, after we record this session, we're going to say," All right, when are we going to do this again? What are some topics?" We have this back and forth, and you had a good suggestion the other day. You and I have talked a lot about pre-submissions many episodes, but we haven't really gotten into the logistics or the mechanics of the contents of a pre-submission. I think it's a great thing to do today. Maybe a good place to start is remind folks what a pre-submission... I think the official term from the FDA, if I recall is a Q- submission. I don't know why we have two different words, but what is a pre-submission and when do you think a company should consider requesting one?

Mike Drews: Yeah. Great question, Jon, and as always, thanks for the opportunity to talk to you and your audience about a very important topic, and that is communication with the FDA. In this particular case, communication in the form of a pre-submission meeting or a pre- sub. You're right, some people refer to this historically, as a Q- sub. It really doesn't matter. Shakespeare said a rose by any other name still smells as sweet. What we call it, I don't really care. What's more important is that we actually do it. Simply put, a pre-submission meeting is an opportunity to talk to the FDA before you actually make your submission. Whether it's a 510-K, or Denovo, or PMA, what have you. And before we get into the details of it Jon, out of curiosity, do you want to take a guess how many pre- sub meetings were requested by the industry with FDA last year in 2020? Throw out a number. What are you thinking?

Jon Speer: Wow. First of all, I didn't actually realize that this was data that was tracked and available. Let's see, there's usually about five to 6, 000 or so 510- Ks. I'm doing a quick mental math in my head. There's usually a few dozen PMAs and et cetera, et cetera. A thousand. Let's go with a thousand.

Mike Drews: Well, great guess, Jon and you're right. This is tracked as part of the minutia requirements. The statistics are updated quarterly on FDA's website. We can provide a link to that information as part of the podcast. But last year in 2020, there were 3, 306.

Jon Speer: Holy cow.

Mike Drews: claims were submitted to the FDA. In this year alone in 2021, thus far, there were a little over 1500. Clearly, the popularity of the program is increasing as over what it was a few years ago. Although, interestingly enough Jon, to parse those statistics a tiny bit further, not all pre-submission requests actually involve an actual meeting. About two thirds of those 3, 300 in last year, two thirds of them actually requested a meeting. The other one- third, the communication with the agency was just the written patient, an email. In my opinion, Jon, I don't want to say that's a mistake, but that's a missed opportunity to say the least.

Jon Speer: Oh, for sure.

Mike Drews: I always, always, always request a meeting with the FDA as part of my pre-sub. I can't think of an exception to that rule, Jon. Now today, as everybody knows with COVID, the meetings are being held virtually via teleconference, kind of like you and I are speaking right now, but I always request a meeting. And just a tiny bit more statistics that the audience might be interested in Jon, because these are questions that companies ask me all the time. How long does it take to get a response from the FDA for a pre-sub? Now I've averaged these out across the different types of pre- subs, but the average time for a written response from FDA is out 62 days or about two months. Between the time FDA actually receiving your pre- sub package and getting a response from the agency, I would figure roughly about two months, sometimes a little less, but that's the average.

Jon Speer: And just on that, if I recall that's pretty close to the window in which the FDA is charged with responding anyway, right? I think if I recall, from the time of submission to hearing a response is supposed to be 60 days, is that right?

Mike Drews: Well, it depends on the type of pre-sub.

Jon Speer: Oh, type. Okay All right.

Mike Drews: There are about half a dozen different types of pre- sub. I'm not sure if it's necessary to get into those words, and to be honest with you, Jon, whatever numbers that are in the guidance and for the benefit of the audience, FDA did update the pre- sub guidance. The most current version is from January of this year.

Jon Speer: Okay. Well, we'll provide a link to that.

Mike Drews: So January 2021, those numbers are pure theory.

Jon Speer: Yeah.

Mike Drews: 100% theory. What I'm giving you is the reality.

Jon Speer: Okay.

Mike Drews: There's a big difference between the degree and the reality.

Jon Speer: No.

Mike Drews: Another thing that I should mention, because some people don't understand this, is a pre- sub is purely optional. It is never required. A company can choose to do a pre- sub or not, but it's almost always my advice to a company. In other words, prior to making the actual submission, I will almost always recommend doing a pre- sub first for a whole bunch of reasons, which I would hate to get into Jon. But the only time that I don't recommend a pre-sub is if the submission is what I consider to be a slam dunk submission. In other words, if there's no questions about the regulatory pathway, maybe a 510-K, there's no questions about what's predicate or the product code. There's no questions about the testing. There's no questions about the clinical data. There's no questions about anything. That would be what I consider a slam dunk submission. As you can imagine, Jon, in the 30 years that I've been playing this game, very rarely do I get involved with what I consider to be a slam dunk submission. I almost always suggest to my customers a pre- sub meeting. I'll share with you some other statistics that I've shared with you before Jon, when you look at 510- K's that are submitted to the FDA today in 2021, about 75% of them are rejected first time out of the box.

Jon Speer: And it's crazy that that's still the case, but it is still the case.

Mike Drews: It is still the case, and in the 510- K world of those 75% that are rejected, 85% approximately, the numbers fluctuate a little bit but not much, about 85% of them are rejected specifically because of central equivalents or the lack thereof. And for those in the audience that are working in the class three and the PMA universe, the statistics are even worse. About 89% of PMAs are rejected first time out of the box. They result in what are called major deficiency letters. Bottom line, Jon, no matter how you slice it, I think that statistics are appalling. They're embarrassing as an industry. I think we, as an industry have devolved, not evolved, but devolved to the point of essentially treating FDA is our elementary school teacher. In other words, here's my homework assignment, please mark it up and give it back to me. And I don't know about you, Jon, but that my opinion, that is not the way this game is supposed to be played. The biggest advantage of having a pre- sub, which again, optional not required, is greatly mitigating if not completely eliminating, those statistics I just shared with you, Jon. One last thing, and I would love to have your thoughts on this, but I pride myself on being in the minority, not the majority. In other words, I am not in the 75 to 83, 11 to 25%. And there's a lot of ingredients that go into my secret sauce to that, but the most important is communication with the agency in advance of the submission. Whether it's in the form of a pre- sub or something else, it doesn't matter, but communication. What do you think before we get into the nitty gritty details? What do you think of that, Jon?

Jon Speer: I have a few reactions. First, that's the number of pre-sub. I'm surprised, pleasantly. I'm glad to hear that the program is growing in popularity. That's good. It seems to me, I grew up in this industry and the era where, you threw it over the wall to the FDA, and you didn't ask questions, and you cross your fingers, and you hoped, and that sort of thing, and that's a terrible strategy. When the pre-sub program came out, I was like," Folks, this is amazing." From a regulatory perspective, this is the best thing since sliced bread, because you get that opportunity to have an audience with FDA. I totally agree with you that, get a meeting, the verbal exchange, especially the face to face exchange, and second best video exchange or video conference exchange, is really good because I think there's some statistic out there that 80% of communication is nonverbal. So, you get to kind of pick up on those sorts of things. That's really great, and cost is reasonable. It's free. I mean, except from my time and my teams time, but when together, but you know, I think as far as things go, this is a no brainer. Why would you not do this? Those are my reactions.

Mike Drews: It's a good point, Jon. First of all, you're exactly right. One of the questions that companies ask me, is there a cost associated with the pre-sub? Unlike 510- K and PMA submissions, unlike 513- G requests and so on, there is no user fee associated with the pre-sub. Although, at least not yet, or they'll give Congress a little bit of time. I'm sure they'll add one. They're missing a tremendous opportunity considering numbers of pre- subs that are happening, but at least there is no user fees. The only cost to the company would be the time and effort to put into the pre- sub, and if you do it properly, Jon, a lot of the information that you put together that goes into the pre- sub will be repurposed right into your submission.

Jon Speer: Oh, absolutely.

Mike Drews: ...Down the road. It's not an academic exercise. One other thing that I wanted to mention quickly, Jon, since you mentioned the video, one of my huge frustrations when I have meetings with companies is people have video meetings where their videos are turned off. Drives me absolutely nuts.

Jon Speer: I know.

Mike Drews: Absolutely nuts. I'm a little old fashioned Jon, but I like to look people in the eye, face to face, because you're exactly right. So much of communication is non- verbal, so much, and if we were having a meeting in a physical room like we would before COVID, we would be able to see that. I'll share with you a quick story. Just happened to me recently, Jon. I was doing a pre- sub with the FDA. One of the reviewers was doing the meeting, I swear to God, Jon, this is a true story, from the grocery store.

Jon Speer: Oh my goodness.

Mike Drews: Because in the background I heard," Cleanup on aisle 12." I was livid. I mean, how unprofessional can you be? Now I said to the company," We should lodge a formal complaint, because I think this was just unbelievable." Of course, the company didn't want to do that. They said," No, no, no," but I believe Jon in treating other people as professionals with respect, but I also expect that to be a two- way street.

Jon Speer: Absolutely.

Mike Drews: And if we were in building 66 at FDA, having the pre- sub meeting as we did prior to COVID, this would have not happened.

Jon Speer: There would not have been at cleanup on aisle three. Speaking of COVID I know in the 510- K world, COVID has had a pretty significant impact on submission and FDA and that sort of thing for lots of reasons, we won't get into all of those today. I've also heard that, this was maybe a month or two ago, that divisions within FDA that review IVD submissions have already communicated, we are not accepting any more pre-submissions for the rest of 2021. Aside from the IVD world, is COVID having an impact on pre-submissions from your point of view?

Mike Drews: Yeah. Great question, Jon. The short answer is yes, and some cases subs have been delayed. For example, I've gotten responses back from the FDA week to evaluate this right now, we're putting it on kind of hold. It's going to be a maximum of about 120 days or four months before we can get to it. In some cases, they've been flat out rejected and you're exactly right. It's happening in the areas visions and CDRH that are being most heavily impacted by COVID. IVD's, In Vitro Diagnostics are one of the two branches. The other branch that's being impacted significantly is the respiratory branch.

Jon Speer: Yeah, makes sense.

Mike Drews: These are the two areas within CDRH that are absolutely getting slammed, and I can understand like everybody, all organizations, we only have a certain amount of bandwidth, and I can understand if FDA needs to delay, in some cases, flat out reject a pre- sub. What I don't understand, Jon, and this is a huge frustration of mine, is FDA, as far as I know, and I don't think I'm wrong about this. They have not announced anything publicly about this. Why should a company spend so much time and money preparing and submitting a pre- sub only find out that FDA doesn't have the time or the bandwidth or the resources to address? As a matter of fact, Jon, I have reached out, as you know, I have a number of personal friends of mine in the agency. I have talked to division director and branch chiefs. I won't mention people's names, obviously, to find out," Hey, can you just give me indication if I submit a pre- sub to your particular brand, will it be accepted?" They basically tell me off the record, because they can't stand anything officially because FDA has not announced anything about this officially, but off the record, it's up to the division director or the branch chief at that particular time when the pre- sub is submitted to make that determination, if they have that bandwidth or not. I understand completely COVID is having a big impact on everybody, including FDA. I understand that. What I don't understand is that these things are not being discussed publicly. People talk about transparency, but I don't see any transparency here.

Jon Speer: Well, I guess curious question, in the cases where it's being rejected, you having to wait 62 days to find out about that rejection or is this something that's happening relatively soon there after submitting?

Mike Drews: Yeah, and that's a great question, Jon. Fortunately, at least in my experience, and as you know, Jon, I do a lot of pre- subs. On average one a month, if not more. I've not had to wait 62 days to find out that they're not going to have a pre- sub. Usually, if they can't have a pre- sub or if there's going to be a delay, I find out within several days or a week or something like that. Believe me, if I had to wait two months, then they told me that we're not going to have a meeting. That would be... Oh, don't even get me started on that one.

Jon Speer: Yeah. Yeah. I guess the other thing that is a little curious to me, I mean, positive, I think part of this to your point earlier, like you said, the activity of preparing a pre-submission is not purely academic. Even if a company prepares pre-submission and for whatever reason, it's rejected, you didn't lose anything. It's still a valuable exercise, right?

Mike Drews: Absolutely correct, Jon, and kudos to you for looking at the glass being half full, as opposed to half empty, but you understand the point. If FDA is going to be limited on resources, and again I completely understand, there needs to be a public disclosure of that, and companies should have a formal mechanism where they can reach out to the FDA. They shouldn't have to do it informally through people like me. I mean, I have relationships with people so, most of my interaction with the agency is actually not formal, but rather informal. But a lot of people don't have those relationships, Jon. They should have the ability to find out maybe not to 100 degree of certainty, but is it likely that FDA, the particular group within FDA that they will be talking to, is it likely that they will be able to have a pre- sub within a reasonable period of time?

Jon Speer: I mean, how awesome would it be.

Mike Drews: This is not an unreasonable question, Jon.

Jon Speer: I know this is crazy talk here, but how awesome would it be if FDA had dashboards where... But anyway, I digress. All right. Moving on to more of the substance of pre-submission, how do you define success when you're going through a pre- sub activity? Maybe one measure of success is yes, it didn't get rejected. We're actually going through the process, but I guess a little bit more in depth. When you work with companies, how do you determine what is a successful pre-submission?

Mike Drews: Yeah. Great question, Jon. As we talked about earlier, there are a lot of pre- subs that are happening with the agency, but in my opinion, most of them are not successful. Not successful. The question is, what is a successful pre- sub? My Mike Drews definition of a successful pre- sub, quite frankly, is when everybody walks out of the room agreeing with me. That is an achievable goal. I've had some pre- subs, actually, that were so successful, FDA agreed with everything that we said, that the company decided that," Oh, gee, it's not necessary to have a meeting, because we all agreed. Right?" But if you apply that criteria across the board, in our industry, Jon, I hate to say it, but most pre- subs are not successful. As a matter of fact, I'll share with you one other quick story, Jon. After one of my pre- subs, this was a little while ago prior to COVID, I was in the room with the company and the senior VP ranking person from the company came up to me after the meeting. And he said," Mike, the pre- sub went great. FDA essentially agreed with most everything that we said, let me ask you a question. Do you think we over- prepared, because we spent a lot in preparing for this meeting?" And I said," Gee, that's a good question, but let me ask you a question. If the meeting didn't go so well, would you have asked me the same question?" To have a successful pre- sub, in other words-

Jon Speer: That's a funny story, actually, some irony to it.

Mike Drews: Yeah, some irony to it, you're right, Jon, but it's possible by my definition of success, it is possible to have a successful pre- sub, but it does take a significant amount of time and effort to achieve that.

Jon Speer: Absolutely. All right. You mentioned the guidance document has been updated in January of 2021, and folks, we will provide a link to that guidance document in the show notes for this episode. I've read that document, I think it's clear enough, but I guess for those folks listening along at home, what are the contents? What should be included in a pre- sub and how much detail and information should I have? I guess I'll bundle a few questions in here together. I'm often asked," Oh," or actually, the reaction is often," Oh, I'm way too early for a pre-submission." What are your thoughts and reactions to that?

Mike Drews: Great questions, Jon. First of all, I'm not going to insult the audience intelligence by reading the guidance. Let me give you my Mike Drews response in terms of what goes into a pre- sub. But I'm just curious, Jon, you mentioned that you read the pre- sub. Did you happen to look what is on the cover of that pre- sub? And that is, specifically, final guidance. Why the heck.

Jon Speer: Final?

Mike Drews: Why the heck is FDA still perpetuating this terminology of draft versus final when it comes to the any guide?

Jon Speer: I don't know.

Mike Drews: It just boggles my mind. I mean, anybody thinks that there's not going to be another guidance at some point in the future on pre- subs, give me whatever it is that you're smoking, because you know, I want some.

Jon Speer: Revision control. I mean, this is something we do in industry. I mean manage your versions and revisions of documents and not that big a deal.

Mike Drews: Yeah. But more importantly, in terms of the content of the pre- sub, look, it's very, very simple. You have to give FDA enough information about your device, what it does, how it works, your testing methodology, your clinical data plan, your regulatory strategy, all those things that you want to talk about in order to sit down and have an intelligent conversation about your device. That's it. It's as simple as that, right? FDA breaks out the pre- sub up into different sections and so on. Quite frankly, you can follow their advice or not how you organize it. I could care less. What's much more important is you have to give them enough information to have an intelligent conversation about whatever it is that you're wanting to discuss, because this is the first time that the reviewers are seeing your device. Now let me take my advice a step further, Jon, because one of the most common questions I get is, what exactly do we put into the pre- sub? You can read the guidance from now until the sun burns out, like all regulation, it's not going to answer that question. Here's my Mike Drews advice, every single sentence, every single word, every single punctuation mark should be put into your document for one reason and one reason only, and that is to help FDA come to the answer to whatever question that you're asking that you want them to come to the answer to. In other words, it's what the lawyers call ask a leading question.

Jon Speer: Leading the witness. That's what I was going to say.

Mike Drews: Leading the witness.

Jon Speer: I mean, it's your story. You know that this is what I tell people.

Mike Drews: That's exactly right.

Jon Speer: This pre-submission is an opportunity for you to tell your story, what you're trying to do, why it's important, and those sorts of things. That's why you have the audience with FDA is to communicate and articulate your story about your products, and your devices, and your plans going forward.

Mike Drews: That's exactly right. And as you know, Jon, from reading that guidance, there are only three requirements of requesting a pre- sub. One of them, which makes my blood pressure go up every time I read it, is you must ask FDA a question. Which to me, it puts us into a condescending kind of a position treating FDA as my school teacher, as my professor, and I look at them as my equal, but I don't put them on a pedestal by any means, right? My advice to companies is, you want to ask them leading questions. As I said, everything that goes into your document should be put in there for one reason, and one reason only, to help FDA come to the answer to the question that you want them to come to. And one other thing about the guidance Jon, as you know from the guidance, FDA provides long laundry list of example questions that one might ask in a pre- sub. Well, suffice it to say Jon, I would never in a million years, use any of those questions.

Jon Speer: I know.

Mike Drews: Because they think they're absolutely horrible questions for a whole bunch of reasons,

Jon Speer: They are bad. Let me pause you for a moment, and so, tell your story and the contents of the pre- sub, and then the questions should be telling your story. You're leading the witness. The question is the opportunity to get the witness to, I guess, answer in the way that you want them to, and I always warn people when they ask questions, like, sorry, there are a lot of really dumb questions. And I think there are a lot of really dumb questions that could be put into a pre-submission. Don't ask things like,"Do you agree that this is a good predicate? Should I file a 510-K?" And those sorts of things, those are not useful questions in the grand scheme of things, but you know, you've got this audience with the FDA and there needs to be art in those questions. This is not a yes, no question. Most of the time you're trying to extract from the agency that they get the message that you were trying to communicate. I warn people, be aware of what you ask, because how you ask that question, you may get an answer that you don't like.

Mike Drews: And that's part of my job as a regulatory consultant, Jon, is to mitigate that chances of getting that answer that you don't like. As a matter of fact, this is what I call controlling the discussion. Leading the witness, as you said, a moment ago is the very appropriate metaphor.

Jon Speer: I want to chime in now. I don't want people to think that that's some sort of nefarious thing, right? We're not suggesting that you do something sketchy. Leading the witness, because you know about your product, and your story, and what you're trying to do a million times more than any FDA reviewer will ever know it.

Mike Drews: Correct. And to your point, Jon, and I apologize if I'm putting the wrong kind of a spin on this, because I don't mean to be nefarious in any way.

Jon Speer: Right.

Mike Drews: It's not my intention.

Jon Speer: I just wanted to clarify that.

Mike Drews: No, no, but let me explain further, because I think this is an important point for our audience to understand. One of the ways that a lot of companies begin their questions, as you just did a moment ago, does FDA agree that...? Quite frankly, I don't care if they agree or not. That's not the objective here. The way that I start these questions is, and please notice how I parse my words, Jon, because I'm doing so very carefully. Based on my labeling and my technology, has the company demonstrated that the 510-K is the most appropriate pathway? Based on my labeling and med technology, has the company demonstrated that the testing matrix is appropriate? Based on the labeling and technology, have we demonstrated that a clinical trial is not necessary and here's the reasons why, or clinical trial is necessary, and here's the reasons why. That's exactly what I mean by phrasing the question properly and leading the witness, not does FDA agree? Because once again, that's putting them in a position of being the teacher or something like that. Grading my work.

Jon Speer: Right.

Mike Drews: That's not the objective.

Jon Speer: That's how you're going to ask FDA to agree. Chances are, they're going to take the most conservative angle. If you say," Oh, does FDA agree that I don't need this or blah, blah, blah?"

Mike Drews: And I'll give you a perfect example. You know, one of the three common objectives that I have in virtually all of my pre- subs is the clinical data. As you and your audience know, I work as a consultant for the agency. I'm on the FDA side of the table as well sometimes. And I've seen companies come in and basically ask the FDA the question, do you think I should do a clinical trial? Well, what do you think FDA is going to say?

Jon Speer: Yes.

Mike Drews: Of course, you should do a clinical trial.

Jon Speer: Yes you should.

Mike Drews: ...Andyou should use 500 million patients. Of course, I'm exaggerating to make a point.

Jon Speer: Slightly, but yes.

Mike Drews: Instead, the way I phrase that question is, based on the device's labeling and technology, have we demonstrated that a clinical trial is not necessary and here are the reasons why, or based on our labeling and technology has the company demonstrated that a clinical trial is necessary and this is a clinical trial design executive summary of what it's going to look like? Right? And speaking of the questions, Jon, the three common questions that I typically ask in virtually all of my precepts are as follows. Objective number one is on the regulatory strategy on the pathway to market. In other words, have I demonstrated that it's a 510-K, Denovo, or a PMA or whatever, that's objective number one.

Jon Speer: But based on, not just saying again, I want to reiterate this FDA should I file a 510- K? FDA, how about a Denovo? I mean, you're saying based on the information we just shared with you about the labeling, blah, blah, blah. So on and so forth. Does FDA agree that this path that we've demonstrated that this is the path?

Mike Drews: Correct. And as a matter of fact, Jon, let me thank you for asking or pointing that out because let me take it a step further. When I go to the FDA and I say, based on my labor and technology, have I demonstrated that the 510-K is the appropriate path? I usually don't stop there. The second sentence is: have I demonstrated that a Denovo is not necessary?

Jon Speer: Ah, see, that's the secret sauce.

Mike Drews: Similarly, when I go with a Denovo, I say," Have I demonstrated that the Denovo is appropriate? And have I further demonstrated that is not necessary?" Why am I doing this job? And most companies are not doing this, but this is exactly why most pre- subs are not successful. Because I want to give FDA not just every opportunity to agree with me, but I also want to give them every opportunity to disagree with me. In other words, I've seen so many people make this assumption, Jon, they do a pre- sub with the FDA. They say a certain thing didn't come up. FDA didn't raise a certain question. Therefore, there's no question to be asked. I don't make that assumption. I want to make sure I want to be explicit as I possibly can. Like I said, I want to give them every opportunity, not just to agree, but to disagree. What we're talking about, Jon, I've used the metaphor, the poker game many, many times. The company and the FDA has a poker game. It represents what we're talking about here, Jon are not the rules of poker because you can read those rules of the guide. What we're talking about here is the strategy, how to win the game. That you are not going to find in the guidance. That you are not going to find by listening to a podcast from FDA or anywhere else. That's what you are going to hear when you're listening to our podcasts, and when you listen to the webinars that I do, because I go beyond just the rules of the game, we talk about the strategy.

Jon Speer: Right.

Mike Drews: That's a great point. So, just to close the loop on that, because I think we've got to wrap this up soon is, objective number one is usually the regulatory strategy, 510- K, Denovo, PMA, what have you. Objective number two is usually under testing matrix, because one of the most common reasons why submissions are rejected is because a company does a certain number of tests and they submit it to the FDA, and FDA throws the submission back in their face because FDA says," Well, we want you to do these one or two additional tests."

Jon Speer: Yes.

Mike Drews: Very amateur mistake, it's an elementary mistake, and it can be greatly mitigated if not completely avoided by presenting your testing matrix, all of the tests that you're done or planning to do in support of your submission. Now, another thing that people should understand is FDA's policy, and I agree with them on this, that they will not review data during the pre- sub, that actually occurs at the point of the submission, but what they should and what they will review is your plan to collect the data. The testing matrix such that as long as you do all of these tests and the data shows what you say that it's going to show, then that's enough to get the ball rolling.

Jon Speer: Can I give a reaction to objective two?

Mike Drews: Please, absolutely.

Jon Speer: I just think it's a good business sense. Number one, because just about any medical device that you're going to design and develop and hope to bring to market has probably some type of testing component to it in some way, shape, or form. Usually that is the most expensive or some of the more expensive things that you're going to do during the design and development of that. And if you just make carte blanche decision that says," Well, we're going to do everything under the sun." That's not pragmatic. It's not useful to anyone, and then if you take a minimalist approach and you don't find out until the time that you submit 510- K or other type of regulatory submission, and you get questions back, you thought you were at the end of the game, and now you're really back in the middle or maybe the beginning. Pre- sub is generally more something that you do early on. Not always, but generally it's something you would do early on. Getting some feedback on your testing approach, I think just makes great business sense.

Mike Drews: I agree with you, Jon, and let me take that example one step further. You're exactly right. Testing can be time- consuming and expensive, but imagine that happening in clinical trial. In other words, I can't tell you the number of times I've seen, especially in some of the largest medical companies on earth, and I just laugh when this happens, because it's such an amateur mistake. They do a clinical trial without vetting it with the FDA first because it's a non- significant risk device and they're not required to. So, they submit it to the FDA and FDA says," Gee, we would like to see these additional one or two and now they have to do a whole clinical trial over again to but that information. Can you say, ka- ching, ka- ching, ka- ching? This is such an amateur mistake and it can be so greatly mitigated if completely avoided by, as you suggested, Jon, taking it to the FDA in advance in the form of a pre- sub, or however you want. Objective one is usually the regulatory strategy. Objective two is usually the testing matrix. The third objective that's common in most all of my pre- subs is the clinical data plan. In other words, we are not going to do a clinical trial and here are the reasons why, or we are going to do a clinical trial and here's the reasons why. And it's interesting, Jon, some companies that I work with, they say," Well, we're not planning on doing a clinical trial, but we don't want to bring that up with the FDA as part of our pre- sub," because they say," Well, if the FDA expects to see a clinical trial, they're going to say that during the pre- sub." Why would a company make that assumption?

Jon Speer: Don't know.

Mike Drews: Remember Jon, as I said earlier, well, I don't either, but so many couples please do.

Jon Speer: Silence is not a set in these scenarios.

Mike Drews: Like I said, I want to give FDA not just every opportunity to agree with me, but also to disagree. If my strategy is not to do a clinical trial, and as you know, Jon in the medical device world, unlike in the drug world, clinical trials aren't uncommon, they're the exception rather than the rule. But if you're not planning on doing a clinical trial, why not bring that up as part of your pre- sub, just to make sure that FDA sees it the same way, because if you make your submission without bringing it up and FDA says," Gee, that's great. Now show us your clinical data," And you're like a deer in the headlights.

Jon Speer: Again, it's the wrong time to find out. If you're at that stage.

Mike Drews: Wrong time to find out, and one last thing that I'll say on that last point, Jon. Oftentimes, when I see a medical device company come in and say to the FDA, we're not going to do a clinical trial. They give some excuses, but at the end of the day, Jon, it's a thinly veiled excuse that they don't want to do a clinical trial because they don't want to spend the time and the money to do it.

Jon Speer: Right.

Mike Drews: Even if that's true, that's not legitimate excuse for not doing a clinical trial. Here's the way I phrase it. If I were to do a clinical trial, what additional information would I gain that I don't already have from the literature, from comparisons to other devices, like a predicate from subject matter experts and so on, and so on. In other words, I'm not arguing that I'm not going to do a clinical trial. Instead, I'm arguing that if I do it, I'm not gaining any additional or new information.

Jon Speer: There needs to be a value element to it.

Mike Drews: Exactly. Correct. Exactly. Correct. Those are the three main objectives that I have in most of my pre- subs, and some pre- subs we'll add additional objectives depending on what the goals of the company are. But the last thing that I'll mentioned on the objectives, Jon, there's no place anywhere in the entire pre- sub process to draw more attention to something than to put it as a pre- sub objective and a question. I've seen some companies go in literally with 18 or 20 or more different objectives, and in my opinion, that's a huge mistake. Now on the flip side, I also, one of my FDA reviewer friends shared with me an example where they had a company come in with one objective and 60 sub- parts. You can add these things up in many different ways, but I think you and your audience, Jon, appreciate, what I'm trying to explain here in terms of those three things.

Jon Speer: No, that's very helpful. I appreciate the objectives. Super helpful. Any final thoughts on the top? And I know you could go on for days on the topic of pre- sub, because I know you're very passionate about this vehicle, I guess, or tool and the value that a company can achieve from this done properly anyway, but any final thoughts on pre- subs before we wrap up this episode?

Mike Drews: Yeah. Well, again, Jon, I appreciate the fact that you say that I'm passionate about this topic. I guess I'm passionate because I see so many companies running into so many delays.

Jon Speer: They've still got work to do, right?

Mike Drews: ...And make so many mistakes that most of them are just totally avoidable, you know, totally avoidable. To wrap this up, and we've talked about some of these issues not just today, but in the past Jon, don't treat the FDA as their elementary school teacher. Here's my homework assignment, will you please mark it up and give it back to me? This brings me to my regulatory mantra and that is: tell, don't ask. Lead, don't follow. Go into the FDA with the pre- sub. Here's my device. This is the way that it works. This is my regulatory strategy. This is my testing matrix, and so on, and so on. And be very confident, not just here's what I'm going to do. This is another thing that differentiates my approach from so many others, Jon. I like to not just justify what I'm going to do, but I also justify what I'm not going to do, because again, I want to give FDA every opportunity, not just to agree, but to disagree with me. But here's what I'm going to do, and here are all the reasons why, and here's what I'm not going to do and here are the reasons why. And if you do this in advance of your submission, I can just about guarantee because this is not theory to me. This is everyday reality. I can guarantee that your submission is going to go through the agency with far fewer delays, far fewer questions then if you don't have this communication to come in advance.

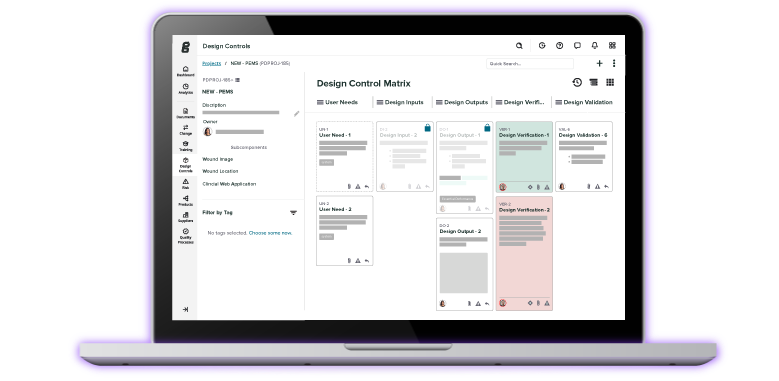

Jon Speer: I appreciate you sharing that. I mean, the biggest thing that I picked up, and it seems so obvious after you say it, is that last little bit. Oftentimes, when I ask a question, I'm asking it about this certain thing that I'm interested in. I don't think about the other use cases or possible scenarios. I think that's very, very important. So, I appreciate you sharing that. Folks, Mike Drews, he is very passionate for reasons shared, but to reiterate, we have a lot of opportunity for improvement in our industry and both Mike and I in our own respective worlds and practices and areas of expertise are trying to make a difference, trying to improve upon a really great opportunity for the world. Why not do the best that you possibly can to bring new products and technologies to the market and want to think about this from a more strategic, holistic perspective, stop treating regulatory agencies as a check box and your teacher and those sorts of things. You wants to think about things a little bit differently and improve upon your practices, especially when it comes to pre-submissions and all things regulatory. Well, Mike Drews from Vascular Sciences is your person. Reach out to him, he'd be happy to have a conversation with you. And of course, if you want to build your entire architecture of your processes and procedures and quality management system, well, that's what Greenlight Guru comes in. We have the only medical device success platform on the market today designed specifically, exclusively, and only for medical device companies. That's right. You can manage your design and development, your risk, your document management, and all of your post- market quality events, things like campus and complaints, all in a single source of truth. So go check it out. Www.greenlight.guru, be happy to have a conversation with you. As always, want to thank you for listening to the Global Medical Device podcast. It's because of you, that this podcast is still the number one podcast in the medical device industry. So, thank you, continue to spread the word, and until next time, this the host and founder at Greenlight Guru, Jon Speer, and you have been listening to the Global Medical Device podcast.

ABOUT THE GLOBAL MEDICAL DEVICE PODCAST:

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Nick Tippmann is an experienced marketing professional lauded by colleagues, peers, and medical device professionals alike for his strategic contributions to Greenlight Guru from the time of the company’s inception. Previous to Greenlight Guru, he co-founded and led a media and event production company that was later...