Pros & Cons of Being a Physician turned MedTech Inventor

Do you fear needles and the associated pain? No one understands this fear more than physicians who see it firsthand with their patients day in and day out. And one physician in particular set out to do something about it.

In this episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast, Jon Speer talks to Dr. Amy Baxter, CEO and founder at Pain Care Labs. Amy discusses the pros and cons of being a physician, entrepreneur, and inventor of reusable, physiologic medical products to eliminate unnecessary pain.

LISTEN NOW:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some highlights of this episode include:

- The medical world works on 2-D pharmaceutical schematics, but doctors’ minds work on three dimensions. Physician inventors see the whole body, person, and need to develop effective medical products.

- Physician inventors think they know everything, so it’s difficult for them to follow ISO 13485 and painstaking medical device development and not get frustrated.

- The time duration for Amy’s innovation and invention journey took years to get patents, meet regulatory requirements, and address the opioid crisis.

- Pain management is esoteric and subjective. Amy encourages physician inventors to fall in love with their problem, not their solution. Pain, chronic or not, is a real problem.

- Amy shares life lessons for physician colleagues with innovative ideas. Find a group like Greenlight Guru or GCMI to understand navigation early on. Branding matters, so choose wisely.

- Also, Amy advises physician investors to not get hung up on non-disclosure agreements (NDAs). Nobody steals an idea, they steal a medical product.

- Amy expects the future of pain management to include multiple specific energy devices in people’s medicine cabinets to use before and after surgery. Mechanical stimulation will be the primary one because it’s easy and safe to use.

- Buzzy® is a palm-sized device that combines cold and mechanical stimulation to block pain and improve muscle soreness, blood flow, and recovery. The VibraCool® Cryo-vibration product, VibraCool’s M-Stim, is 2-3.4 times superior to electrical stimulation (TENS) for physical therapy. It has demonstrated 35% fewer opioid tablets. Also, a lower back pain device is in clinical trials and expected to be released this year.

Links:

ISO 14971 - Application of Risk Management

NIH Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR))/Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR)

Global Center for Medical Innovation (GCMI)

Medical Device Podcast, Ep 186: Building a Startup in the MedTech Industry

Greenlight Guru YouTube Channel

MedTech True Quality Stories Podcast

Memorable quotes by Amy Baxter:

“We see the whole body, we see the whole person, and we see the need.”

“The downside of being a physician inventor is that we both feel like we know everything.”

“Wanting to be able to do something is really the push that puts a lot of physicians into the entrepreneurial space.”

“Fall in love with your problem, don’t fall in love with your solution.”

“Try your idea out on someone who does not love you.”

Transcript:

Announcer: Welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast, where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Jon Speer: On this episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast, I get to speak with Amy Baxter and you have the size of the name because I realized that after the fact that I misspoke some point in the podcast, but Amy Baxter is the CEO and Founder at Pain Care Labs. You can check out more about her invention, really cool simple products. Top of pain management, paincarelabs.com, all one word. I really think it's cool. I've been blessed through my career to have the opportunity to work with a lot of physician and vendors. We have really cool, awesome product ideas in the medical device space, so I hope you enjoy this episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast. Hello, and welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast. This is your host and founder of Greenlight Guru, Jon Speer. It's always fun to have the prep before we hit the record button, try to get the levity going and Amy Baxter did just that for me today. She's got me laughing this morning. Joining me is Amy Baxter with Pain Care Labs, the Chief Medical Officer and CEO. Amy, welcome.

Amy Baxter: Thank you so much, Jon. I'm delightful to be here and to have our pre- warmup session.

Jon Speer: Exactly. It's like, get in the game. Let's get ready to go. Now I'm pre- coffee, so I'm going to pour some coffee here in a moment. Hopefully I'm able to speak in complete sentences, but so far I seem to be doing just fine. But what I was hoping we could talk about today is that you're a physician, you're an inventor of a medical product and I've worked with physician inventors in my career and there's some nuances to that. I thought maybe you could share some of your experiences, the ups and downs, the good, the bad, the ugly, that sort of thing.

Amy Baxter: Well, at least you started with good, because I think when people think physician, entrepreneur, inventors, they got a little bit ugly, bad, good, in that order.

Jon Speer: No, my experience is it's all been really very positive. What I've learned from working with physicians is you have a problem that you're faced with in a patient scenario that you're trying to be inventive to come up with a way to address that problem. I've had plenty of prototypes handed to me from a doctor that, well, they were pretty creative as far as how things were taped and glued and snapped together. But it works and it's like... But it wasn't something that they could do on scale.

Amy Baxter: I think that the great thing about physicians and physician inventors is first of all, that we think very three- dimensionally. Despite the fact that the medical world works on two dimensional pharmaceuticals, schematics, doctors' minds work on three dimensions. We see the whole body, we see the whole person, we see the need, and it makes it easier for us. We're also familiar with all of the different parts of medical accoutrement and the plastic bits and the nubs and hugs and lure locks. We have a feel for what kind of legos we have at our disposal that are already sterile that we can put together. The great thing is that we visualize what we need in three dimensions. We see the stuff that's around the hospital that we can use to put it together. I think that the downside of being a physician inventor is that we both feel like we know everything, and so it's hard to come into the world of ISO 13485 and come into the world of really painstaking medical device development, and not get frustrated. Also, it's hard for physician inventors not to get frustrated while they're waiting for this device to be able to be used when they can see the utility and they've already proven to themselves that it's effective.

Jon Speer: I totally agree with that part too. I think the lay person in med device industry does not appreciate or really having knowledge or understanding or tolerance sometimes of that process. I was like, " I built it. Look, I got a prototype. Just make it better and give it to me tomorrow." Which technically I could probably do. However, to your point, there's all sorts of other things that that product has to go through in order to get to that point where I can give it to you and you can use it on the everyday basis.

Amy Baxter: All right. Well, the good part is that that wanting to be able to do something is really the push that puts a lot of physicians into the entrepreneurial space. When I first started with the device for blocking needle pain, I was actually in the emergency department carrying around my little cloogy device that had been duct- taped together. I knew that I couldn't use it but that was where this cognitive dissonance was. I could use it for my kids, I could use it for their injections, but I would have to go through a lot to be able to whip it out and use it in the emergency room. That balance of, yeah, this would work, but I know that this can't be used in this context without an awful lot of regulatory and production support and everything else that goes along with it.

Jon Speer: Do you mind maybe talking a little bit about your aha moment when you came up with the idea? You talked about carrying around an early version, a real early version around the hospital and things of that nature. Maybe talk a little bit about your experience. Because I think your experience, honestly, I don't know how many physician inventors are listening. I hope there are some. But certainly, I think the journey that you went through is also applicable to a startup that maybe has not gone through the medical device process before. I've talked with plenty of people who are doing that are equally frustrated at times. It's probably a good way to describe it. Maybe just elaborate a little bit on your journey and crosstalk-

Amy Baxter: Sure. Well, to contextualize it, what we're doing is mechanical stimulation to block pain. When we first started, it was because I wanted to find a fast way that parents could block the pain of their kids' vaccinations. We're using a really specific frequency that is a noise- canceling headphones for pain. It's been 15 years, so I can tell you that on August 4th, 2004, trying to think about ways to overcome the pain sensation. I've been for maybe a year or two, thinking about, you rubbed your bumped elbow, or you bang your hand with a hammer and you shake it. Or more to the point, you burn your finger and you stick it under cold water, and so long as the cold water is running, then the burn pain goes away. The aha moment after noodling for two years on how do you make the sensation of motion to block pain, the aha moment was driving home in the morning from an overnight shift and my hands were on our steering wheel, which was vibrating because we hadn't gotten the tires balanced and forever. When I reached for the door of my house, my hand was numb.

Jon Speer: Wow.

Amy Baxter: It just clicked that you don't need running water, which was very messy. It didn't work. You don't need a rubbing thing, which is difficult to pull off mechanically. All you need is vibration. Wasn't exactly right. I ran into the house. I had three little kids and they glom onto me before I go to bed after my overnight. I said, " Hey, hey, get the Wartenberg wheel." Which is this thing that you use in neurology with a pizza cutter, but with cokie, with the needles coming out.

Jon Speer: Sure.

Amy Baxter: Sure, like you have. Like you do. I got that out and we had a TurboFlex 4000 massager that I got off some homeless entrepreneur who was selling them when I was in residency. All right, TMI, but I put the vibration on, I did the Wartenberg wheel on the kids' hands and they could still feel it. I was like, " All right, forget it. It didn't work. I'm going to bed." My husband's a boy scout and he said, " Well, in the scouts we use frozen peas. What have you combined frozen peas and the vibration." Put a bag frozen peas, put the TurboFlex on top of it, and those two sensations together blocked pain enough that on my three- year- old and one- year- old, I could leave marks on their fingers on their hand, wipe where you would do an IB and they couldn't feel it. I was never going to be mother of the year because I leave marks on my children and inaudible people about it. It was a big enough deal. It's like hair's standing up and goosebumps and it's like, this blocked pain on a child. We did a video of it, recreation of the moment. Then I went to bed. From that it took two years to get patents filed, three years to get an SBIR, two years to get them made and launched in 2009, went on Shark Tank in 2014, didn't quit practicing medicine until 2016 because my colleague used the device to block pain from a total knee arthroplasty without using any opioids, because he was in recovery. That is the time duration of the journey. But to tell a physician that they won't believe you.

Jon Speer: Well, a couple of things. Well, first the question. How is the, then three- year- old doing now? Is he a he or she? Do they remember that moment?

Amy Baxter: They don't remember that moment, but they certainly... All three of them are now over any degree of needle fear. They had part of the SBIR that I got from the NIH, NICHD. Shout out to Eunice Shriver. But part of what I got helped me understand why children are afraid of needles and grow up afraid of needles. It's a totally new thing. I have testified before the Department of Health and Human Services a couple of weeks ago on adult needle phobia, which came from that research. Bottom line is where now, since 1982, we're giving four to six- year- olds boosters so they can remember they can be traumatized and then they stay afraid of needles. My kids now are all in college or graduated. They are fine and they certainly feel very empowered to address both needle pain, but also any kind of pain. It's really nice that they are able to deal with their volleyball elbow and report back on how it worked for them.

Jon Speer: All right. I know the journey has been long and at times... Well, always I'm a fan of serendipity. Things have to happen in a certain reason. Maybe the opiod crisis, that was a really interesting angle on that. I hadn't really thought about that so much, but you're right. So many procedures, the post- recovery time involves a lot of opioid therapy and no wonder there's such a huge addiction problem in this country right now. That's awesome that your colleague was able to use the product and not have to take the painkillers. That's huge.

Amy Baxter: It really is huge. I think that one of the reasons, ironically, why our process is taking a long time is because mechanical stimulation is disruptive and there is this discrepancy between, if you have a very finite solution like an arterial filter or a better tip blade of a laryngoscope. Something like that is actually much faster to get into circulation, because it's a very finite solution, it's very obvious improvement over a previous problem. Whereas when you actually have a new type of concept technology, particularly because the research around blocking nerves and really understanding how gate control works, most of that's published in the last five years. Incorporating a whole bunch of different ways that you can use a technology makes it take a lot longer to get it accepted and to get it out into circulation.

Jon Speer: I have to imagine too, something like pain management, it's very esoteric and subjective, right?

Amy Baxter: Yeah, absolutely. One of the things that I have loved learning along this journey is little aphorisms people say about your product or being a manufacturer or whatever, and I love the idea of, fall in love with your problem. Don't fall in love with your solution. Because for me, my solution was for vaccination and needle pain and needle fear. The problem actually was pain and had I fallen in love with pain earlier, then I would have been more open to the idea that our solution was actually much more appropriate for the issue of opioids, the issue of pain management, the issue of specific things that cause suffering rather than one particular utility that's a really narrow part of someone's life.

Jon Speer: I think I shared when we spoke before that I used to work as a product development engineer and I worked with anesthesiologists and emergency physicians and surgeons and that sort of thing. I don't remember who brought this idea. It was so long ago and I don't think I'm sharing any proprietary trade secrets. But the concept was to try to develop a catheter- type solution that would be placed basically along and as an incision post- surgery. Essentially the first prototype that I came up with do know that the garden, soaker hoses, do you know what talking about?

Amy Baxter: Sure, I got kids.

Jon Speer: Just the water just oozes out of it.

Amy Baxter: The drip irrigation kind of thing.

Jon Speer: Yeah. That was my first thought, is like, " Well, if we could put something like that along the incision just ooze this out.

Amy Baxter: Like an on- cue or something with inaudible that delivery for pain management afterwards?

Jon Speer: Yeah. But still, it was cool to think about but really difficult to measure and to demonstrate. Plus then again, you're still delivering some, one of the canes to the people and it's like, I don't know. It just seemed like a bad way to go, but pain is a real issue. What was your aha moment when you finally realized that's the problem that you need to be chasing?

Amy Baxter: I was very deaf to it for a while. People use our device for in- vitro fertilization, they use it for arthritis injections, a lot of the ones that are really painful. The Humira or Enbrel or the infusion and things like that. The initial product we have is this little cute b- shape for kids. When people were doing that, they were like, " Actually we use it on our hip and actually we used it on the shoulder. Actually, it's been very effective for the elbow soreness." And I was like, " That's nice." But didn't go anywhere until my colleague confided that he'd been in opioid recovery for 20 years and had been putting off getting a TKA for three years and ask whether or not he could use it. I asked him to... I made data sheets. I was like, " Great. Why don't you do your PT with and without, and here's some data sheets." And afterwards he said, " I'm so sorry." I said, " It didn't work?" And he said, " No, no, no, I couldn't take it off. I didn't do it." You don't have any... I can tell you how it works.

Jon Speer: That's raw data.

Amy Baxter: But I got no data for you. That was in actually 2015. I had to give notice of my clinical practice. At that point was doing mostly procedural sedation, so lots of ketamine protocol, fentanyl, and gave notice three months later, went full time and so we developed a better embodiment with a compression strap, bigger ice packs so that you can put it around. Then I broke my neck and so then I made one for my shoulder and neck pain, but the moment was really him telling me it worked and it was that same cognitive dissonance that I'd felt at the beginning. Is I'm going to have to disrupt my normal practice if I decide to invest the time to do this. When he had that, it was that same anxiety of, I can't know this and keep practicing medicine normally. I need to commit and really be all in for this.

Jon Speer: All right, so I want to take a brief break. When me come back we'll talk a little bit about tips, pointers, et cetera, for inventors that are out there. But while we're taking this break, tell folks a little bit about Pain Care Labs. Obviously you've shared a couple of the early version and then a more recent version. But talk a little bit more about some of your products and where people can find out more about your products and services.

Amy Baxter: Sure. Well, paincarelabs. com is our website. We do have a shop that is affiliated with it that has Buzzy, which is the needle pain, IVF, any of the models we have for healthcare use or for home care use for injections. Then VibraCool is the line for knees, elbows, plantar fasciitis. We have four different VibraCool devices that are all in the$ 80 range or lower, and we are introducing on the show... I'm going to show you our new VibraCool pro, which is for post- surgical pain that we're testing now. When we come back, I also have a surprise for you crosstalk.

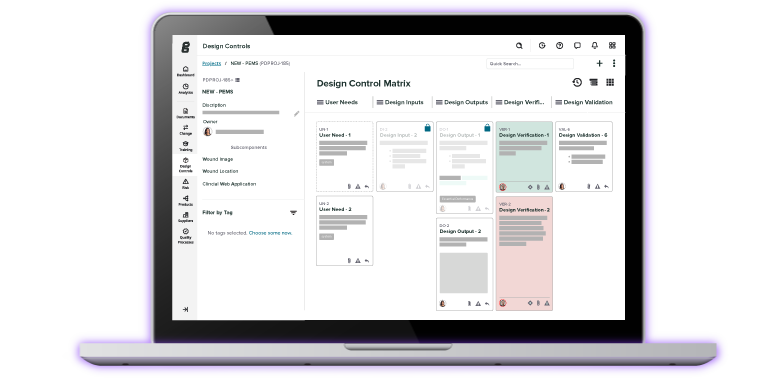

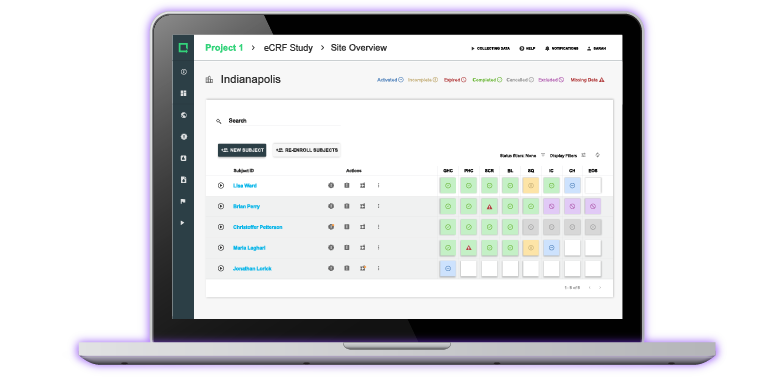

Jon Speer: Well, I can't wait. But pain is a real problem. I've talked to so many people. Inventors, suffers, et cetera, throughout the years that want a solution for all these things. I really I'm glad that we got connected. I have to thank Duane Mancini from Project MedTech. Folks, that's another great podcast at least I do. By the way, Project MedTech, go check it out. I think he's on Spotify and iTunes. But he made the connection and we had a chance to chat and I felt like I was talking to like a star because of your Shark Tank experience. Which I'm curious about. I don't know if we'll get through it on air today. But anyway, I want to remind folks, to Greenlight Guru, we're here to help. We work with entrepreneurs and inventors all day, every day. We have solutions to help you manage your design control activities. If you don't know what that is and you're an inventor, you probably should call us because that's really important from a medical device perspective. We also have workflows to help you manage risk through the entire process. Again, if you don't know why that's important, there's a reason. We'll explain it to you happily, but all of our solutions align with medical device regulations and requirements, so FDA 20, ISO 13485, ISO 14971, code 11, EUMDR. I can go on and on and on, but hopefully you get the point. If you're interested in learning how we might be able to help you, and you don't have to be an inventor. You can just be designing a medical device or working with products that are already on the market. Either way, we're a medical device success platform. Go to www.greenlight.guru. We'd be happy to have a conversation to understand what your challenges are and see if we might have solutions that help address those. All right, let's get back to the conversation. Amy, tips and pointers or advice that you may have for a physician colleague, that's got an idea? What should they do and when should they do it and what shouldn't they do and that sort of thing. What are your life lessons, I guess, through this journey that you can share?

Amy Baxter: Not to suck up too hard, but one of the most important things is to find a group like Greenlight Guru, or in Atlanta we use GCMI.

Jon Speer: They are great. Love GCMI. They're a customer of ours actually, so yeah.

Amy Baxter: Tiffany Wilson, she's now in Philadelphia at the Science Center and CEO there. But super good friend. Just understanding how to navigate early is a really important part. Universally, I think advice for a physician is that it's going to be so much more complicated and requires so much more thought up- front than you think it is because all of us are ready to go. Especially if you're an emergency doctor or an orthopedic surgeon where you're used to playing with tools and having mechanical things. You're like, " I don't see the barrier here. I got this thing, it fits here. Let's go to town." The process for medical devices is much more complicated. Having a strategy for regulatory, having a strategy for reimbursement, having a strategy for market channel, having understanding of channel, knowing how things are sold in different areas, all of that stuff. Even 15 years in, one of the reasons that we are morphing our VibraCool to a VibraCool pro and that we also have branded this mechanical oscillatory stimulation therapy, is realizing that M- STEM is a concept that we needed to brand and branding matters. The other thing is that having a device that has two different forms of the stereotactic mechanical stimulation delivery makes it more likely to be able to be covered by center's Medicaid and Medicare, just like a 4- lead TENS can be discovered rather than a 2- lead TENS. Even though our single unit is 3. 4 times better than a TENS unit for pain, it's harder to get it covered if it's already on the market for consumers. There's just all this inside baseball stuff, having a native guide is a really good way to start. That's the first thing I would say. I think the second big piece of advice is don't get hung up on NDAs. Because nobody steals an idea, they steal a crosstalk-

Jon Speer: Non- disclosure agreement.

Amy Baxter: Sorry, yes.

Jon Speer: That's good.

Amy Baxter: Whole new set of acronyms, I have learned. We've got to too many TLAs.

Jon Speer: Tell me about them.

Amy Baxter: The three- letter acronyms that are different ones than we use in medicine. But that's one of the big things, is that so many people are so sure that they've got this amazing idea and they don't want to tell anybody because just telling the idea is going to make someone so much money that they will be on a beach with little umbrella drinks for the rest of their lives.

Jon Speer: Sorry, I'll just chime in. I had a story about that. I was working with an ER physician. I had an idea and I don't know that it was patentable per se, but nonetheless, we were able to come up with a pretty quick solution and I don't know, it got ugly. I just got to the point where I'm just like, " This is not worth it for me. I'm trying to help you but you're turning it into something I'm trying to steal your idea." Which was unfortunate because it was a really simple thing. Hopefully he turned it into something. Let's just hope that's what happened. But people want to help. I'm an engineer. I like to solve problems. I am not going to go off and do a patent on your idea. I'm going to try to see what I can do to share my experience to help you on that journey.

Amy Baxter: In some ways I think it's our hit- the- lotto culture. Everyone has seen or heard of someone and so there's availability heuristic. You have this concept because you can think of that person that did it and got super rich. Everyone thinks that their idea is so good on its own that it's worth something. Aside from for perhaps Michael Crichton selling the idea of DNA and Amber for Jurassic Park for a million bucks, there're very few ideas in products that are worth it. Now, this doesn't mean go to your buddy who works at J& J or your buddy who works at Zimmer Biomet and tell them the idea. But somebody who's in your position, somebody who is another physician entrepreneur, getting hung up on NDA just makes you harder to work with and harder to get advice and people want to help.

Jon Speer: I think that last bit is important too. I was going to offer, if you are an inventor, you may say, " Well, my product fits in the portfolio of J& J or Medtronic or Boston Scientifics, these giant monolithic companies, and it's true it may fit in their portfolio. I think what a lot of people want is an audience with those companies. My advice to you is that's not the company you want the audience with. You want the audience with the scrappy, maybe a little bit beyond startup, but somebody is hungry that's going to work hard for you and be assessable to you and give you their heart and soul and passion along with yours. If you work with one of the larger companies, great companies but they're not going to be as passionate about seeing your product through the journey as maybe somebody like you or me, or maybe another design firm or something of that nature so choose wisely. If you need some help on advice on who and how to choose, I'd be happy to chat with you. I know lots of folks who work our this space, sometimes they blend into the woodwork. They're not obvious. Sometimes they might be your next- door neighbor, the mechanic. There's lots of ways, so find those people.

Amy Baxter: I remember there was a moment when I was spray painting some Buzzy prototypes out in front of our house for a clinical trial that we'd gotten funding from the Mayday Foundation, and so they do work in pain relief, they're in New York. Shout out to Christina Spellman. But we've gotten some funding and so... not much funding. I'm spray painting prototypes. But my neighbor who was a Michigan grad, Jerry Friedman's there and he's like, " This is great." And I said, " Yeah, next year we'll be on a beach drinking umbrella drinks." And he's like, " Well, the usual time to exit is between seven and nine years." And I said, " Well, this is going to be so much faster. This is such a good idea." That was 12 years ago. One thing you said, Jon, that I think is really important but people don't get that ties into my idea of fall in love with your problem not your solution, if you're outside medical device systems, you may not understand how your idea fits into what a company needs. You also probably don't understand how to show this thing so that people can see what the value is. Our device and technology is a perfect example. It was probably a mistake to make it for kids, or least to make the design for kids because it conflated what's actually a very sophisticated physiologic technology into a toy or a distraction. But the other part is not really seeing where it fits into the spectrum of where we fit best so figuring out what your thing does best. We throw a lot of spaghetti at the wall of athletes and runners and plantar fasciitis and it does those things well, but the time that all of us on our team use it is when we really hurt, when we've got a pinched nerve in the middle of the night. One of our team members had her kneecap, her patellar dislocated because she tripped over a ball her kid threw at her. That intense pain as where we're best and so trying to then see, " Okay, people that are in the intense pain business, what solutions are they using now? And how do you frame this so that an M- STEM platform looks like the intense pain relief that these guys are looking for?" That packaging branding channel understanding is never something that a physician is going to get right out of the shoe.

Jon Speer: For sure. Folks, if you're out there with an idea, I'll talk to anybody. Because I love working with entrepreneurs and inventors. I think in startups it's a passion of mine. If you have an idea, be fore warned, I've been known as the dream killer at times too. Sometimes I'm like, " There's not a need for that or that sucks." I probably won't be that harsh the first time that I talk to you, but I'll give you an honest opinion and it's my opinion. You may find somebody else that has a different opinion. If you don't want my opinion, that's cool. My advice to you though is, get outside your circle a little bit. If I go ask my mom about something that I did or idea that I had, she's going to say, " It's amazing." She's my mother. Get outside your circle, talk to somebody that's going to be objective. They're going to tell you the truth. Those are people that are really important if you have an idea. It's going to hurt if they're going to tell you something that you don't want to hear, but you should go outside of your circle to get some feedback.

Amy Baxter: That's so funny. I tell people the same thing. I say, " Try your idea out on someone who does not love you. Now, it hurts less if somebody who doesn't love you thinks it's a stupid idea, but try your idea out on somebody who doesn't love you. If you go to a professional and they don't think it's a good idea, maybe go to two, but accept that. Because this is 12 years of working on something and that's crosstalk-

Jon Speer: Making capital.

Amy Baxter: ...after the idea and the funding was already in place.

Jon Speer: Talk about-

Amy Baxter: All right, well, so then I'm going to ask your opinion, Jon here. I've got you... What channel or what part of a medical device company would I show our technology to and at what point?

Jon Speer: Well, usually these types of things are handled by, within larger companies, the function called business development. Usually there's a discipline or somebody that's in that or a group of people that are in that capacity. Some companies will also have business units and business unit leaders. I would say some of the more progressive companies in the industry they realize, " We make medical devices, physicians use medical devices. Let's tap into that. Let's figure out how to be symbiotic within that ecosystem." Some of my previous employers, we've worked with physician venters all the time. You look through their portfolio of products and it was doctor this, doctor that, doctor that. The physician's name became part of the product almost as a way to not memorialize, but symbolize their contribution.

Amy Baxter: Are you saying that maybe crosstalk. This is my surprise for you.

Jon Speer: I'm very familiar with that one. That takes me way back.

Amy Baxter: If anybody's listening, what you're seeing is a Melker Emergency Cricothyrotomy Catheter Set that I have in my closet, in my bathroom because you do. Cook's catheter system that you worked on.

Jon Speer: Interesting. A Cric kit for those that don't know what that is, basically it's an emergency airway. We all have probably heard these stories or seen the movies where there is an airplane, there is a flight and somebody's choking on an M and M or a peanut or whatever and then all of a sudden-

Amy Baxter: Some mash, mash when Radar O'Reilly jams the ballpoint and-

Jon Speer: Essentially that's what a Cric is. It's a little more elegant than that, but more or less conceptually that'll give you the idea. But anyway, Richard Melker, Dr. Melker, fascinating man. Physician inventor, prolific physician inventor. I don't know what he's doing today. Reminds me of that I might want to reach out a bit. He has had so many ideas, started so many companies, but that's a little unusual. He has a passion for that now. Others out there listening, you may be passionate about your idea. Follow Amy's advice, be passionate about the solution or solving the problem. What was your saying again? I'm butchering it all to hell.

Amy Baxter: Fall in love with the problem, not the solution.

Jon Speer: Fall in love with the problem, not the solution.

Amy Baxter: Because if you fall in love with the problem, you'll iterate better solutions. But if you get stuck with your one solution, then you're searching for a problem to put it on. Instead, for me, I ended up getting to learn an enormous amount of pain physiology and that's where the innovation comes. Is once you really understand what's happening in the body, then with that problem, then you're like, " Okay, so if we stimulate this particular nerve, then it's the pain canceling headphones type analogy." But the reason that TENS units aren't working is because you're not stimulating the right nerve in the right frequency but you really got to dig into the understanding of the problem so that you can get to that level of sophistication with your solution.

Jon Speer: But-

Amy Baxter: Although Cric is a tube, so there's not as much to it. But not to dismiss Dr. Melker at all because having Cricothyrotomy kit is very comforting.

Jon Speer: There's one of the ones I've worked on, there's a newer version of that. It has a balloon cuff on it so it looks more like a tray than a Cric. There's another version that's beyond or newer than that. And they might have something, I haven't been at Cook in a long time, so they might have something else yet still. But that's one of those things that's really interesting because you hope you never... How many people have you Criced? Probably zero or close to zero.

Amy Baxter: I have been present at two Crics but I have not... intubated plenty, but never had to do the Cric.

Jon Speer: It's like insurance, really.

Amy Baxter: No, no, it's total emotional security. It really is funny. Because every emergency doctor thinks about these situations. It's like, " All right, so what's the worst that can happen?" And somebody starts choking. You start thinking about, where's my nearest sharp objects. Where's my nearest tube- shaped thing. Am I going to go big- pin Radar O'Reilly on this guy or... You just start getting ready just in case you get called on to do it. When you actually got a Cric, then that takes all of the, how do we MacGyver this thing out of the equation. Then it's just like, " I got a Cric kit up in the bathroom. I'll just go run and get that."

Jon Speer: My short story about first experience Dr. Melker, when I started at Cook in the critical care division, my boss, he would always send engineers to a anesthesia course at Shands Hospital at the University of Florida in Gainesville and it's like a week- long course. I went down there with a colleague, a brand new kid right out of school, engineer, been on the job maybe a couple of months, but so go down to Shands Hospital. We've got to figure out how to navigate to this course is here and this course is over here. They're right across the wall from each other but you know how hospitals are designed. You've got to go down, over, up, cross and all that. It's literally a maze but we're trying to get to this cadaver lab where there's a cricothyrotomy workshop for med students and we are going to participate in this thing and we're trying to figure out where is this? Of course they keep the dead people... I'm sorry, it's morbid, but they keep the dead people in the basement of the hospital in the morgue. Eventually somebody helps us. We find the room where this cricothyrotomy workshop is happening and-

Amy Baxter: Mind you, these are donor bodies. They keep the dead, dead in a morgue in a different place from crosstalk.

Jon Speer: I get that. All right.

Amy Baxter: They don't randomly go get somebody.

Jon Speer: These are people who-

Amy Baxter: They not going to care.

Jon Speer: But anyway, we finally come in, but the mini course is already a few minutes underway and the person leading the discussion has a few different cricothyrotomy kits. There was one called this and one called that, but one of them was called the Melker. He's teaching how to use all of these different Cric kits to med students and my colleague and I, we had the opportunity to do this first. I didn't even have time to process, Oh my God, there's a cadaver. But anyway. We're practicing and using this and during the demonstration he says, " Well, my personal favorite of the three options is the Melker Cricothyrotomy kit." Okay. The course was over, or the demonstration was over and we had to go to the next thing somewhere else in the hospital. We found a med student who was willing to show us and as we're walking through the halls, we were like, " By the way, who was the doctor doing the demonstration?" She said, "That was Dr. Richard Melker. I'm like, " Well, it makes sense." But anyway, the reason he liked the Melker, this is inside baseball, is it uses this Seldinger technique, and you know the Seldinger technique all day, every day. If you're in an emergency situation, you don't want to figure out some gadget and how it works. It's got needle-

Amy Baxter: The Seldinger technique is just shoving a wire into where you want it to go to make sure that you've got clearance. Then once you've shoved the wire in where it goes and you know it's clear, then you can put a bigger, fatter thing over it and you've got a native guide already stuck in it.

Jon Speer: More or less, yeah. Needle, guide wire-

Amy Baxter: Just for those listening at home. Out of curiosity, did you have, at some point that night after your first cadaver experience, did you have just shakes or weirdness of having to confront your mortality because you had been touching somebody who was dead?

Jon Speer: I didn't, no, no. I was fascinated by and my journey into med device completely, not accidental, but it wasn't by design. I have a chemical engineering degree and when I was in school, I took a couple of biomedical engineering electives. Truth is the biomedical engineering professor that was teaching these classes pretty easy way to get an A. Let's just say I needed a couple of those at school but anyway... But I never thought about entering that as a career, but as I was in my senior year, my options as a chemical engineer were to go work for an oil company in West Texas and I had been in West Texas. It smells like cows mostly because there're so many cattle there. Or the other option was to work at a potato chip factory in Iowa. I don't like potato chips, so I was like, " Well, I don't really want to do either of those." But I had friends that had interviewed and had jobs with Cook and they're like, " Well, they're hiring more people." I interviewed and got a job, but that's really what it was. About a year, a year and a half in, I think I told you this before, I developed an introducer. Designed an introducer, double- lumen introducer for cardiac output and I was present the first time that was used clinically. I realized that this is not a cadaver, this is a live person and that person wants be alive when they leave here. That was my epiphany I had, that wow, what I do really matters.

Amy Baxter: Matters.

Jon Speer: Good or bad, hopefully good. But improving the quality of life became my North star at that point.

Amy Baxter: Most of the people that I know in medicine had one night after being really intimately involved with their cadavers or somebody else's cadaver, but just realizing that you are holding life in your hands and ironically, it was by holding death in hands that you realize that your barrier to normal interaction with physical bodies is different from everyone else's. And that is a similar kind of thing. We don't tend to get imposter syndrome the same way that other fields do because we spend 12 years getting to the place where we're very comfortable taking responsibility for someone's life, with every decision or prescription or anything else we do. But I think that for many of us, it's the physical boundaries that are such a change. I think that's one of the reasons why early on, physicians have hard time having empathy for anyone who fears needles. Because a needle is one of the least- invasive things that we do to people's bodies. We don't go into medicine if it bothers us so there is a disconnect, but I think really, you start becoming in a different approach to humanity when you first are holding that cadavers body.

Jon Speer: This gave me chills when you were talking about that so that's super impactful. Amy, at a point where it's good to start putting a wrapper on this particular episode, any last- minute tips, pointers, advice, dos, don'ts that you want to share to the listening audience?

Amy Baxter: I think I wanted to just selfishly say a little bit about how excited I am about this understanding of pain and pain management and I really believe that the future of pain management in the next probably five years is that there are going to be multiple specific energy devices that people have in their medicine cabinets that people use before and after surgery. I do think that mechanical stimulation is going to be the primary one because it's the easiest to use. It's the safer pacemakers. It's something that anybody can put on and there's no ambiguity. You know it's helping or it's not. I think that that's something that's really exciting and so I'm very grateful to you for giving me the opportunity to talk about a new platform and also to talk some about the things that I would have done differently. I think the only other thing I would say is I really do believe, now that I'm sitting on scientific review panels that NIH, SPIR and STTR funding is a fantastic way to get up to speed with your company quickly, because all of the aspects that you need to do for these grants, which are one to five million, they're enough to get your idea really off the ground and started. But it opposed the rigor and it gives you an understanding of what kind of design controls you're going to need, what kind of commercialization plan you need. It's a good way to understand and to get the discipline for your new device if you decide to go that way and get some funding on the backside of it.

Jon Speer: For sure. I love the bit about pain management. We have to do something differently. As a society, we've become so conditioned to just pop it a little pill in our mouth and it's not healthy and that pill leads to other pills and that sort of thing and other downstream modalities and issues.

Amy Baxter: We're actually working on a campaign for kids with Buzzy to say, choose bugs, not drugs. So we have our lady buzz and our Buzzy. Again, this is from the people who have one in their house. They tell us that if their kid bangs their elbow or their kid gets stung by a bee, they now go run and get Buzzy because they know that it blocks the pain. How much better just to make a cute little thing to put around, so for every booboo, you've got this supercharged booboo bunny that is helping kids learn not to go for a pill but to go for some physical solution.

Jon Speer: My best friend when her girls were younger, she had this, I think it was supposed to be, but it was like a little ice pack that was shaped like a pig. It was tiny. She'd always say, go get the booboo pig. They didn't have anything, but they did become conditioned to just like, go get the booboo pig, which was cold ice. It didn't have any mechanical stimulation, but-

Amy Baxter: But ice has got a whole different... That's why we use both ice and vibration for a lot of things, is because ice as a whole different circulatory, descending, noxious, inhibitory control pathway. It certainly does work and so it's a totally different mechanism, but putting the two together is so interesting.

Jon Speer: For sure.

Amy Baxter: But yeah, crosstalk.

Jon Speer: But I love the mission and this has been one of the most enjoyable episodes that I've had, certainly in the modern era at the Global Medical Device Podcast with video, so I think we should play it along. Folks, this is talking with Amy Howard, the CEO and Founder at Pain Care Labs. You will learn more about their products. Paincarelabs, all one word, no hyphens, no spaces, . com, so go check it out. Again, if you're out there and navigating this medical device journey, whether you have done it 1, 000 times before, this is your first time, Greenlight Guru, we're here to help. Go check out www.greenlight.guru to learn more about our medical device success platform. Again, we'd be happy to have a conversation with you to understand your challenges, your obstacles your frustrations through this journey. It can get there and it's not for the faint of heart, but we're here to help you. Just reach out to us, let us know how we can help. If you're a physician inventor or just an inventor or an entrepreneur, reaching out to me. I love this stuff. I almost said others inaudible. I love this stuff. It's so much fun. I'm a kid in the candy store when I get to learn about ideas and inventions. I just think it is the coolest thing ever, so I'd be happy to chat with you. But anyway, as always, host and founder Greenlight Guru, Jon Speer, and you have been listening to the Global Medical Device Podcast.

ABOUT THE GLOBAL MEDICAL DEVICE PODCAST:

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Nick Tippmann is an experienced marketing professional lauded by colleagues, peers, and medical device professionals alike for his strategic contributions to Greenlight Guru from the time of the company’s inception. Previous to Greenlight Guru, he co-founded and led a media and event production company that was later...