The idea of “research versus development” can be highly controversial and much-debated among medical device circles.

Where does the “R” end and the “D” begin?

David Amor, aThere are a number of aspects of “conventional wisdom” that need to be challenged. Frankly, these common assumptions are often wrong. Let’s take a closer look:

Free Download: 5 Practical R and D Tips for Medical Device Developers. Click here to download PDF.

Why start design controls early in development?

There’s often an assumption that starting design controls “too early” will slow the whole process down. It’s something I hear all the time; “Jon, we can’t do that, it will hold us back.” On the other hand, people are often confused about when the right time is to start with design controls.

David refers to a point made by FDA; “Some manufacturers have difficulty in determining where research ends and development begins.”

What’s the answer? Design controls start when you start. They begin when you’re ready to demonstrate to FDA and the world that your product is under a state of control. It’s up to your company to determine at what point you have reached “good enough” so that the development phase is initiated. Anything

Are you looking at research the wrong way?

That word “research” is a key thing for people to understand, although it varies from one company to the next.

Practically speaking, a lot of organizations are shifting away from calling product engineers “R and D.” There will often be a team tasked with research, then another team called “technical development”, or “product development.” The view is shifting - people are understanding that the research bit at the beginning really is just that - proving the concepts and

Where there is new technology or IP, there is definitely going to be a lot more going into the research part, to demonstrate that the technology is safe and effective. Afterward, it’s about taking that proven technology and putting it into a medical device - the “D” side.

I’ve come across several engineers who love the idea of being in a team that does the research, often because they see that as an opportunity to tinker around with concepts. The thing is that this doesn’t do the development side any favors. If you’re thinking you’re just going into research to be creative, you’re missing the point about being focused on an outcome. Demonstrating that your concept has merit is one of those outcomes.

Another thing that’s a key to understand is that research is an excellent time to identify key pieces for the development side. For example, understanding from the view of the end-user what is important to them. This should be a major objective of research!

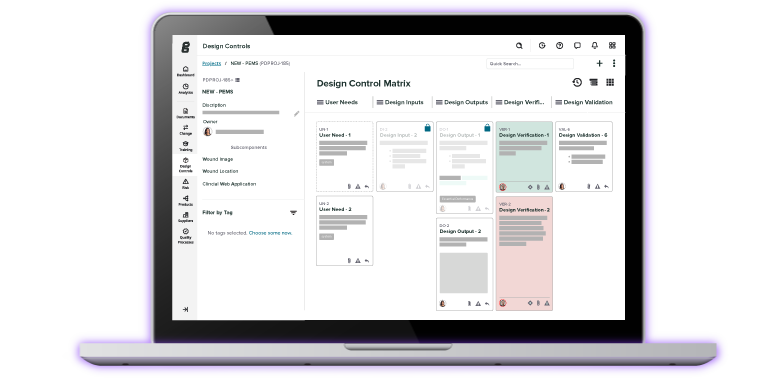

Here you’re really laying the foundation for design inputs. You won’t have an entirely fleshed-out list, but you’ll have a good start, with things that can be smoothly transferred to the development side.

David often sees a mixed bag of design inputs, from marketing, regulatory and other sources. He likes to collect everything in a “catch-all” to create a traceable matrix for design inputs. How do you ensure that only the most critical items from the research phase get clearly carried to the development phase, and documented through design controls?

Will early design controls slow you down?

“Conventional wisdom,” says design controls are a large amount of paperwork and that they will slow development down. Watch engineers cringe when you mention them!

People who think this way often focus on prototyping and different iterations, then get quite a long way through the process. Prototypes from this phase haven’t been sufficiently vetted for FDA. As they say:

“[…] manufacturers should avoid falling into the trap of equating the prototype design with a finished product design. Prototypes at this stage lack safety features and ancillary functions necessary for a finished product, and are developed under conditions that preclude adequate consideration of product variability due to manufacturing.”

Researchers and/or developers then get to the point where they’re ready for formal testing, they get results back, THEN they say; “we’d better do our design controls.”

Design controls, in a nutshell, are good engineering. Everything from testing, to validation, to writing down plans, is really a matter of putting those engineering terms within the framework of design controls.

It doesn’t have to take a 700-page document - if you’re doing due diligence and overall ensuring you do the right thing, you should be operating within design controls anyway. Why do people often freak out? Well, sometimes internal policies and procedures make it difficult to change anything once you’re “in design control stage.”

We suggest reviewing those procedures and ensuring that they’re conducive to an environment that meets the regulatory requirements, but allows for some agility in development.

When do design controls actually start?

During the research phase, you’re basically proving that the technology works and that the research behind it is good. When you’re ready to turn that technology into a medical device, that is when you’re really entering the design control phase.

Often, this is not clearly delineated. They’ll have proof of concept and feasibility stages, then they’ll enter “definition” or “development” phase, which is when design controls start to get implemented.

The design control guidance document from FDA is well worth checking out here. This is also consistent with the ISO 13485 view on design controls.

Why design controls are more than a “paperwork” process

It’s important to look at design controls as much more than required paperwork to get you down the pathway to market. They are a needed part of your product development process and can be very effective at catching issues.

David gives the example of a project where the design review revealed they hadn’t fully developed design inputs. This meant they went back and looked for standards that were missing that might have design input requirements that needed testing.

If the review were treated as a “checkbox” activity, these important things might be missed. The success of your product lives or dies based on how well you documented design inputs.

Free Download: 5 Practical R and D Tips for Medical Device Developers. Click here to download PDF.

Final thoughts

“Research” and “development” shouldn’t be conflated - they are two very distinct phases of medical device product development.

Think of your research as providing proof of concept, including market research, business case and feasibility, while development happens after these things

If you’re in the development phase, then you’re ready for design controls. In fact, starting them early can save you many headaches later on. Look at design controls as more than just “paperwork” - they can genuinely be an effective tool for catching issues early on.

Jon Speer is a medical device expert with over 20 years of industry experience. Jon knows the best medical device companies in the world use quality as an accelerator. That's why he created Greenlight Guru to help companies move beyond compliance to True Quality.

Related Posts

The Importance of Good Document Management (And How To Do It)

[VIDEO] How to Calculate the Cost Of Quality: Building the Business Case for your Medical Device QMS

[VIDEO] How to Prepare your QMS for a Successful Medical Device Product Launch (Release Phase)

Get your free resource

5 Practical R & D Tips