.png?width=4800&name=podcast_standard%20(2).png)

Something that you might find surprising is the number of medical device companies that are simply not prepared for an FDA inspection. The bottom line is that you should expect to be inspected.

Today we’re going to be talking to Mike Drues, the president of Vascular Sciences, about the lessons that companies have learned from their not-so-successful FDA inspections. You can learn from them, too!

Listen Now:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some highlights of this episode include:

- Jon’s story of a situation where a company was completely unprepared for an FDA inspection years after their product went to market.

- The difference between not having the required information and having the required information in a format that’s unacceptable to the FDA.

- What companies can do to prevent problems with FDA inspections.

- The importance of knowing what you know and knowing what you don’t know and knowing the difference between the two.

- Why it’s so important to consider the root cause of troubles with FDA inspections. Many times, the root cause is a tick-the-box mentality.

- Best practices for being prepared for an inspection.

- Why an independent audit might not be an effective way to know that you’re prepared for an inspection, as well as tips on knowing whether your auditor is beneficial.

- Why it’s good to purposely inject a problem into your process to be sure that your quality control system will detect it.

- The importance of taking a holistic approach rather than only looking at issues one at a time.

Links:

Memorable quotes from this episode:

“We are talking about people’s lives here... we have the obligation to do what we can to prevent problems.” - Mike Drues

“If you’re going to be in the medical device industry, educate yourself and know what the rules are.” - Jon Speer

“Know the rules. Before you get on the football field... or before you get behind the wheel of a car, you need to know the rules. The medical device industry is no different.” - Mike Drues

Transcription:

Announcer: Welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast, where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Jon Speer: One of the things that surprises me the most, after being in the medical device industry for almost 20 years, is the number of companies that still are not prepared for an FDA inspection. Bottom line, if you're selling medical devices into the United States, you should expect and anticipate that you will be inspected by FDA. Now, the good news is everything that you need to know for an FDA inspection is well publicized, it's readily available, and it's free of charge, so you can definitely find that information pretty easily. The other thing that we get into in this podcast episode is sharing some of the lessons from others who maybe didn't have such good experiences with FDA inspections. So enjoy this episode of The Global Medical Device Podcast.

Jon Speer: Hello, and welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast, this is Jon Speer, your host, the founder and VP of Quality and Regulatory at greenlight.guru, and welcome. Today, we're gonna talk about an interesting topic. I don't know if you'd put it in a category of exciting, but certainly one that all medical device companies need to be aware of. And we're gonna talk about lessons to be learned from recent FDA inspections. Joining me on this discussion this morning is Mike Drues. Good morning.

Mike Drues: Good morning, Jon, thank you for the opportunity to be here with you and your audience. I look forward to our discussion.

Jon Speer: Yeah, and I think we have some good things to talk about, on this particular topic, today. I wanna start it off by saying, I think sometimes that elusive or mythical FDA inspection kind of thing sometimes companies are like, "Oh, that's probably not really gonna happen." Folks, I want you to realize, if you're a medical device company, selling products in the United States, especially Class II, Class III devices, you need to anticipate that the FDA will be there. It may not be tomorrow, but you need to be ready for that at all times because it's very clear that FDA inspections, there's a lot of data to support this, they are on the rise, they are increasing, FDA and this is the way that they really ensure that companies are staying compliant. You can read the news, you can turn on the TV, you can hear some of the really big, big examples from time to time, and while those are interesting, sometimes you don't get a lot of lessons from those. But I think there are some really recent examples, Mike, that have come up in the press recently about recalls, and inspections, and things of that nature. So just share from your perspective, what are some of the lessons that we can learn from some of these recent examples?

Mike Drues: Well, I think, Jon, there actually are an awful lot of lessons that we can learn if we take the time to look for them. And part of the impetus for our discussion topic today was based on a recent report in the Technical Press listing the 10 biggest recalls, medical device recalls of 2017. And one thing that I thought would be interesting to point out to your audience is that 10% of the total number of recalls this year are the so-called Class I recalls. These, as most of your audience is probably familiar, is the most severe type of recall. FDA characterizes a Class I recall as having a reasonable chance that a product, a medical device, will cause serious health problems, or possibly even death. Of course, what does reasonable chance mean? That's open to great interpretation. But it's a reminder to the audience that something that you and I have talked about a number of times in the past, and that is in many cases this is high-stakes Bingo, we are talking about people's lives here, and so we do have an obligation to try to do what we can to try to prevent problems. And why don't we begin, Jon, by sharing an example from your world of your recent situation that you were involved with, with the inspection.

Jon Speer: Yeah, it's an interesting story. And it's not quite a recall status yet, but based on some of the intel that I have on this particular situation, it could lead down that path pretty quickly, actually. I wish I could say this was a unique scenario but, Mike, this story that I'm about to tell you, I've heard and experienced a couple of times. And it kinda started like this, I got a phone call from a company that said, "Hey, we have an FDA meeting coming up," and FDA meeting is a pretty benign thing. Well, what does that mean? And through the course of the conversation learned that this company had recently had an FDA inspection. Now up until this point they had been on the market with their product for several years. The product had 510 [k] cleared and up until that point they had never had an FDA inspection. But then the FDA came to visit and started asking them some really core basic questions like, Where is your design history file? What about your procedures for non-conformances? What about your procedures for complaint handling? And so on. It was a long, long laundry list of things that come to find out that this meeting that this person had mentioned was essentially a visit to the principal's office.

Jon Speer: They have to go sit down with the Compliance Director of a District Office and explain their action plan and what they're going to do about this and number one on the list in this particular scenario is, this company had no design history file, they have no design controls documented. And folks, like I said, this company they've been selling this product for a long time, several years and it's a little alarming to hear stories like that from time to time.

Mike Drues: Well, it's a very interesting situation, Jon and I certainly wouldn't go so far as to say that it was typical or average, but I have similar experiences that I could share as well. Would you characterize the reason for this as simply ignorance? Or naivety? Or what do you think would be the root cause to use the engineering phrase?

Jon Speer: Yeah, in talking to this person and I think, of course, I'm trying to get to that root cause. For me and you, it's so obvious, like, "Okay, is it quality system regulations?" They're public they're publicized, they're readily available and there's a process when you just put in together a 510 [k] submission, it's a pretty good example. If you know what goes into a 510 [k] and the one statement that comes to mind is the truthful and accuracy statement and you understand what that statement even means, then one could assume that, "Hey, it's pretty clear FDA expects me to follow regulations." But somewhere along the way, there's some sort of disconnect and yeah, I agree this isn't the majority of case for sure, but this is maybe an extreme example. But I think it was a little bit of ignorance, I think it was a little bit of naivety. I think in some part the person that was putting together this 510 [k] submission... I didn't peel back that layer but I can suspect that they might have outsourced that or had a resource that helped them with that and maybe didn't dig any deeper, maybe didn't dig into, "Hey, let me see your design history file." It doesn't sound like this company had any sort of audit system in place, they didn't really have any sort of effectiveness checks on their quality system. So, maybe it's ignorance, maybe it's naivety. I'm not really sure which category it is but regardless, it's clear they missed the mark.

Mike Drues: Well, here's my next question, Jon.

Jon Speer: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Mike Drues: Here's my next question because my emphasis not just in our conversation today but overall is not to simply bash people for their mistakes.

Jon Speer: For sure.

Mike Drues: But as you said at the beginning, to learn from them. I understand from the scenario that you just described, they didn't have the paperwork in place, they didn't have the design history file in the systems and so on, but more important to me is the substance. So, did they have, and you may or may not know this depending on the familiarity with this particular case. Did they have the documentation in maybe some other format, in other words in a lab notebook? Or did they have systems in place maybe not in a quality sort of a fashion for dealing with complaints and maybe they didn't have something called a corrective action and preventative action but they had something else that does the same thing? Did they have that kind of information but just not in the format that we're used to seeing it in and that we're required to have it? Or did they not have that information at all? And the reason why I asked that question, Jon, is because as you and I have also talked about in the past, to me everything in the design controls and in quality in general, is what I would consider prudent engineering as common sense.

Jon Speer: For sure.

Mike Drues: So if they had that information in some other format, okay, now it's just a matter of taking what they have and converting it to something that's more industry standard, that's more palatable to FDA. If it's something that they don't have at all then to me that's very problematic and to me that's not just an issue of perhaps getting a warning letter from the FDA. That's an issue of, should they really be working in this kind of a business? What do you think?

Jon Speer: Yeah. Well, I think in this particular scenario I'm gonna have a discussion with the engineering team about some of the challenges or the issues that were identified. And I think in many respects I was encouraged while they didn't know what all the terms that FDA cited them for the meds and the interpretation of that, I was encouraged that when I asked questions like, "What about your requirements for your product?" And they were just able to rattle off a whole litany of different design inputs and things that you would consider requirements for the product. So that was encouraging and then asking about safety testing and things like that. And they were familiar with IEC 60601 and some of the other biocompatibility and some of those things and they had test reports for those types of things. So there was some encouraging things that were discovered during the conversation. But some of the other things that were on the list, it's a mix, some of the other things were not having procedures for purchasing. Okay, well, I know they have purchase orders, I know they have suppliers that they're working with so that was okay. They could tell a story there, non-conformance didn't really have anything capturing those sorts of things, CAPA and complaints.

Jon Speer: So, I think it was a mix. There were some things that they did have and if they were aware of or understood the questions that were being asked by the inspector, they might have been able to find evidence to prove that they had those particular things but then there were just other things specifically around complaint handling and CAPA and non-conformance in their internal audit that they really didn't have anything, a document at all.

Mike Drues: Fair enough. So, a mix is a good way to characterize it. So most importantly for our audience, Jon, what would you suggest that companies do to prevent a problem like this?

Jon Speer: Well, the biggest thing I think that a company could do well... Of course, they could call you or they could call me and we could come in and get them ready but in all seriousness, I think it's really embrace the spirit of what... Being in the medical device industry, it's just like any other thing that you're doing. If you're gonna play football, it's probably important that you know the rules of the game of football. The same is the case for med device, if you're gonna be in the medical device industry, you probably should educate yourself and understand what the rules are to be a medical device company, and it's not a secret, it's pretty well-known, it's pretty, it's readily available. You can go to FDA.gov and enter medical devices and pretty quickly find out all the things. It could be a little overwhelming granted but get a core basic understanding, just the QSR for FDA, it's not ridiculous and it's linked. So you should understand every one of those clauses that FDA has defined, you should know how you do that, how you address that and you should have process and procedure. Just, there's a lot of information that's available. You've written about it. I've written about it. Do your homework.

Mike Drues: Well, I agree with you, Jon. And I love the football metaphor. You should certainly know the rules before you get on to the field and you start playing the game. And by the way, the reason why I asked that question was not to be self-serving. I mean, obviously, you said a company professional like you or I. But to illustrate another important point that we've talked about before, and that is another of the underlining tenets of the philosophy of the design controls, because my understanding of regulation goes far beyond what the words say. One of the basic tenets of the design controls is to remind us of something that Socrates tried to teach a long, long time ago, and that is, knowing what you know and knowing what you don't know and most importantly knowing the difference between the two. So, as Jon just mentioned, if you're new to the medical device industry or you are more on the R&D side and you don't know a lot about the quality or the manufacturing side, make sure that either [A] you educate yourself, which you could certainly do or [B] add somebody to your team who can help you. To use a simple metaphor, Jon, like your football metaphor, imagine getting a ticket from a police officer for driving through a stop sign and going to the judge and saying, "I'm sorry, your Honor but I didn't know that I was supposed to stop when I saw that big red eight-sided sign."

Mike Drues: Unfortunately, ignorance is not a very good excuse. And going back to what I said earlier about recalls especially 10% of them being the Class I recall, that's a problem. So, maybe making this even more pragmatic for our audience, Jon, do you have any suggestions? Obviously, there's a lot of things that are required in the regulatory environment and in the quality environment in terms of the, you mentioned the QSR and so on, but should our goal as a company or indeed even as an industry to have a quality system that meets those requirements? Is meeting those quality requirements enough? And to lead us into this part of our discussion, I thought I could share with you a quick recent example that I have been involved in.

Jon Speer: Oh, sure.

Mike Drues: A medical device software company came to me and they basically said, "We have this software product, this medical device that we've developed, it's all basically done." Now we're looking for somebody to do the V&V testing on it." And if somebody came to you in a situation like that, Jon, would that be concerning at all to you? That they've done all of the development and now they're looking to do the verification and validation?

Jon Speer: Well, let me ask a question, they're not to market with this software yet?

Mike Drues: That's correct.

Jon Speer: Okay. Well, it's an interesting scenario for sure. Maybe it's stylistic. But the way I have always approached product development is, is there's some iteration that's involved to that? Almost to the point where as I'm developing that software, you know it's granted this may not be the formal V&V activities but I have a pretty good idea of what my product is going to do based on just the definition of requirements and the things that I've done. Now, the challenge with this particular scenario is, if I understand it correctly, is that they said we're done, we're frozen, and we've done everything we're gonna do and now we're gonna throw it over the wall to somebody else from a V&V standpoint. Technically speaking, you could take that strategy for sure, but it's a lot of risk to put that high level of activity, that important activity of V&V into the hands...

Mike Drues: Well, I agree with you, Jon, that there is...

Jon Speer: Completely into the hands of another person.

Mike Drues: That there is a tremendous amount of risk. And once again, I love the metaphor that you just used so I've used it myself of throwing it over the wall, so to speak. But the part of the reason why I share that scenario is because from a quality or a regulatory perspective, that is a perfectly valid approach. There's absolutely nothing wrong with it but to me, it's tremendously problematic.

Jon Speer: For sure.

Mike Drues: It makes me question whether or not... I would characterize this actually as a very basic mistake in fact because it makes me question whether or not they really know what they're doing. Never mind, you mentioned risk, risk as we've talked about has many different connotations, never mind quality risk. We're talking about business risk here. If their product is "fully developed" and in the process of now doing their V&V testing, they discovered that there's a problem or something. Now you're talking about having most likely to do engineering changes, design changes is granted because this is a software product, perhaps the nature of software tends to be easier to iterate, to change a line of code, for example, instead of changing material or changing the shape of the medical device or something like that. But nonetheless, it really makes me question whether or not they have a basic understanding of the engineering concepts that are involved here.

Jon Speer: Yeah, I agree. I totally agree. The other thing... Sorry, Mike, I was just gonna say that as you were sharing those other details, I was just thinking that it's like there's a large... For that type of scenario where a company develops and designs its product and then says it's done and throws it to some other firm do V&V, there's a lot of gaps there. Just think about the knowledge, and now you got this other resource who... There's no way that they can have the knowledge and the understanding that went into developing that software product and now they're supposed to be putting this through the rigors of V&V and verification is demonstrating that you designed the product correctly and validation is determining that you developed the correct product and that's a tall order.

Mike Drues: Well, it is a tall order, Jon. I agree with you. And to me, as an engineer, I like to think about root cause and in engineering, root cause is a phrase that we often hear people talk about but rarely ever do I hear people actually get to anything close to what I consider to be the root cause. Usually, they're just skimming the surface. Usually, they're just putting Band-Aids on a problem. To me, oftentimes the root cause is the thing between the people's ears or the lack thereof. It's the thinking. And in this particular case, I think the root cause it's illustrative of something that I think is far too common in our industry, and that is the tick box on a form approach.

Jon Speer: Yeah, for sure.

Mike Drues: We've developed the device, tick, it's done. Now we have to do V&V testing, tick, it's done. And again, this might sound harsh to some people but I really believe for a variety of reasons, anybody that takes that approach to this field and because this is high stakes Bingo think about what we talked about at the beginning with the recalls. They perhaps should not be working in this business. We need to take a more holistic approach. We need to be thinking about everything including V&V testing throughout the process not just as a tick box especially at the end. So, as we approach the end of our discussion I'd like to maybe use this opportunity to talk about a few other best practices, anything that you might recommend, Jon, to the audience either that is required in the regulation or perhaps that's not required in the regulation, to help companies learn and to avoid problems. I have several examples but anything you can think of?

Jon Speer: Well, just maybe a couple of pragmatic tips that companies, and I think you really should think about. You and I have talked about quality and regulatory several times on the Global Medical Device Podcast and just even the last example you mentioned about checking a box on a form so to speak, and I think first is, if you're looking at a quality management system as a check box activity, something you gotta do because the regulations say so, then you missed the point. You should design a quality management system to address your business needs frankly. If you read the QSR and you understand what each of these things says, it's just good business, folks. [chuckle] That's the first thing. And the second thing you may not know how and what and where to focus your time, effort, energy or maybe you don't even understand some of FDA's interpretation about things because if you're new to this and you're reading the QSR for the first time, I could see where it might be a little ambiguous but there's a really good resource. You can go read warning letters that FDA publishes 'cause they're in the public domain, you can read through those. And FDA usually provides pretty good commentary whenever they cite a company for a particular issue. They explain what it is that they were looking for or what they didn't find and that sort of thing. So, use that to your advantage, read and learn what the expectations are.

Mike Drues: I think that's terrific advice, Jon. I would like to just offer a few additional suggestions and one which was actually not on my list but I think I'm going to add it to my list. It's something that you brought up earlier and that is know the rules. It sounds to me obvious before you get onto the football field know the rules, before you get behind the wheel and drive the car know the rules. The medical device business is no different. So, know the rules. That to me is a statement of the obvious, but it's clear from your example then there are others that some people don't. But a few others, first of all, I learned a long time ago not to make the assumption, as many people do and including FDA makes this assumption as well, that if you have a quality system in place and it meets the regulatory requirements that it works, I do not make that assumption. I see a lot of systems in place that meet the regulatory requirements that don't necessarily work or they don't work as well as maybe some people think that they work. So why assume that if your QMS meets the regulatory requirements or the quality requirements that it's working? Assess the efficacy of your system. You know Jon, we're all used to measuring the efficacy of our medical device but most people are not used to thinking about measuring the efficacy of your systems including your QMS. How do you know that it's working?

Mike Drues: Probably the way that most people demonstrate this is with an audit. Well, audits are great if they're done properly but in my opinion this is like the concept of an independent reviewer and the design controls. If you have somebody come in and say, "Oh, you're all doing a wonderful job. Let's have a parade and wave the flag." You may have met that regulatory requirement but in terms of the letter of the law, but you have certainly not met the spirit of the law. You need to have somebody come in and be literally brutal and ask the questions that maybe perhaps other people in your organization don't want to ask. So, make sure that you have an auditor or an independent reviewer who is going to do that. And I can tell you, Jon, in my experience when I do this with companies, and I spend some of my time doing this with companies as you know, I want essentially an iron-clad consulting agreement. In other words, no matter what I say to the company, they are going to pay me. Because if you don't do that then if you have somebody come in and say, "Oh, you're all doing a wonderful job," I don't think you have met that spirit of the law, so to speak. Before moving on to my other two comments or suggestions, any perspective from your side, Jon? What do you think in terms of either the mock audit or the inspector or even the concept of the independent reviewer? What do you think people should be looking for?

Jon Speer: Well, yeah, I was chuckling about the parade. If your auditor tells you everything is wonderful, let's throw a parade. If your auditor is coming back and saying to you that, "Yeah, things look pretty good," fire that person because [chuckle] you want that internal auditor or the independent reviewer that's coming in, you want them to beat you up and rip you apart. You want friendly auditors, the people that are either part of your team or that you've invited in, you want them to provide you with the toughest, most rigorous, most thorough audit that you'll ever go through. Period. That's what you want. You want that to be the toughest thing that you do. You don't want the FDA inspection or the ISO audit to be tougher than your own internal auditing efforts.

Mike Drues: Well, I agree and I would take it even a step further. I would like to think... Well, first of all, perhaps I don't want this to be interpreted as being arrogant but I will sometimes say somewhat facetiously to companies that if they have me come in and do a mock audit or to do an independent review, if they can get past me, they can get past the FDA.

Mike Drues: But you and I are saying the same thing there. And reflecting back to your example that you shared of the company that didn't have the documentation, the design history, file, and so on I would like to think that a good auditor, and just like FDA reviewers there are a lot of them but not all of them are equally as good. I would like to think that a good auditor, if they walked into a situation or that you described earlier where a company didn't have that paperwork in place, rather than whipping out the note pad or I guess, nowadays the tablet and start 483 this, that, and the other thing look a little bit past that. Do they have the information maybe in some other form?

Jon Speer: Yeah, for sure.

Mike Drues: Because that's something that can be then corrected. On the other hand, if they didn't have that information at all, I wouldn't have this power as an auditor but if they're making for example, a Class III device, and this probably wouldn't happen with a PMA device but if it did I would be closing their doors today. That's just not good. Another suggestion I have made to a number of companies over the years in terms of measuring the efficacy of your quality systems is to purposely inject a problem somewhere in your system in order to determine if your system will detect it. This is something that's not required by the regulation, perhaps it should be. And I think personally it's probably a good idea to consider that. Some companies that I work with, Jon, have done that, many have not. Any guess as to why a lot of them don't wanna do that?

Jon Speer: Well, sometimes I think people are afraid of what they're gonna find out, to be quite honest with you, Mike.

Mike Drues: That's exactly right. Yes, yes, you're right. First of all, it's not required. They don't have to do it, but more importantly if you inject a problem into your system and your system does not detect it, now what have you done? Now, you have now totally invalidated your entire QMS system, and that's not a good situation to be in. Just real quick, 'cause I know we have to wrap this up a couple of other recommendations. A theme here, learn from other people's mistakes. In other words, there's constant reports in the literature and elsewhere of warning letters and recalls and so on, from time to time and maybe add this into your quality system as well, maybe on a quarterly basis scour through what's publicly available from other companies. Never mind just competitive companies, but look at the medical device industry across the board and ask the question, Could you have a similar problem in your organization? And if yes, what measures have you taken to try to prevent it? Or, if it did happen, what measures have you taken to try to mitigate the fallout? History does repeat itself over and over again. And those who are not familiar with their history unfortunately are doomed to repeat it.

Mike Drues: And from a product liability perspective, so many of the people that we work with, Jon, are worried about FDA or similar organizations around the world. Well, let me tell you, a growing part of my business is working as an expert testimony for medical device product liability cases. And for a company... I'm not an attorney, nor do I play one on TV, but one thing I've learned in dealing with product liability attorneys is just meeting the regulatory requirements by FDA or the quality requirements by FDA is not enough when it comes to product liability. It's something I've said before, when a company gets a 510 [k] or a PMA, or becomes a manufacturing inspection, that's the academic equivalent of being a cease to, and that just means that you're passing. That doesn't mean that you're necessarily doing a good job.

Mike Drues: And the very last thing is to take a holistic approach. Oftentimes when I see companies, they look at individual problems one at a time. They look at individual complaints. They even look at individual CAPAs one at a time, and they try to address those problems one at a time. And there's nothing wrong with that, that's certainly the first step. But what I would like to see, and again, this is not in the QMS requirements, perhaps it should be, but on some periodic basis, whether it's once a year or once a quarter or perhaps even once a month depending on the technology that you're involved with, take a more holistic approach and take a look at all of your complaints and all of your CAPAs, and try to look for similarities, perhaps that you didn't see when you look at them individually. Kind of like trying to see the forest through the trees. Again, this is not rocket science. You shouldn't have to have a PhD in biomedical engineering to come up with some of these. Most of this to me is common sense, but unfortunately common sense is not as common as one might like it to be.

Mike Drues: So those are just a few suggestions. Of course, there are many, many others.

Jon Speer: Yeah.

Mike Drues: But those are just a few. An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Something to think about.

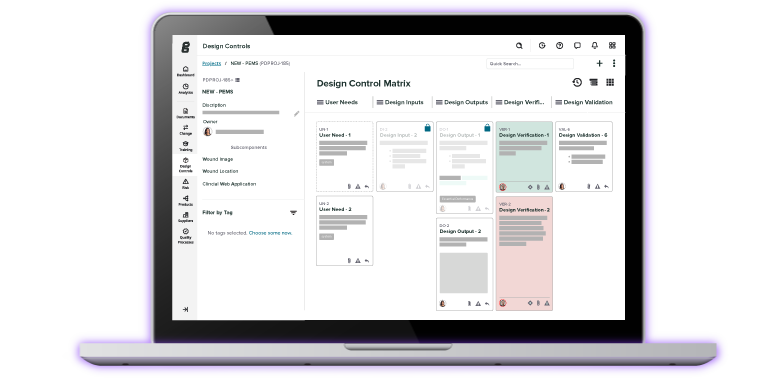

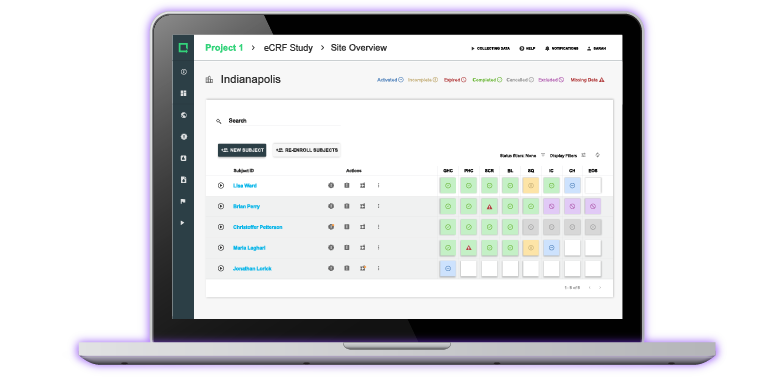

Jon Speer: Yeah. Folks, I wanna wrap this up by saying there's a lot of lessons that you can learn from FDA inspections and you don't have to wait for your turn to learn these lessons. As Mike and I both have shared, there's a ton of information that's readily available for you. If you go through the inspection and it didn't go so well, you can certainly get a hold of a person such as Mike or myself to help navigate. But I know I speak for Mike, we'd rather you call us before so that we can make sure that you've got the proper systems in place and the preparation necessary so that the FDA inspection and any other audits, quality system audits can go as smooth as possible. So do reach out to us. And the good news on the story that I mentioned a moment ago, Mike, that person did contact us and we are working with him at greenlight.guru. And I'm optimistic that we're gonna be able to get him through his challenges because that's one of the things that we do at greenlight.guru. Whether you have done it the first time or many times before, we help companies with their quality management system, we help them understand what design controls are. And we have a software platform that makes that a little bit simpler as well.

Jon Speer: So folks, if you're wondering how you might set up your quality management system, and how to prepare for these types of events in your medical device journey, feel free to give us a call or contact us at greenlight.guru, and we'd be happy to have a conversation with you. So, let me thank my guest, Mike Drues, President of Vascular Sciences. And once again, this has been the Global Medical Device Podcast.

About The Global Medical Device Podcast:

![medical_device_podcast]()

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Nick Tippmann is an experienced marketing professional lauded by colleagues, peers, and medical device professionals alike for his strategic contributions to Greenlight Guru from the time of the company’s inception. Previous to Greenlight Guru, he co-founded and led a media and event production company that was later...