Integrating Human Factors into Design Controls to Improve Patient Outcomes

The relationship between human factors and design controls often creates confusion in the medical device industry.

Today’s guests are Russ Branaghan and Bryant Foster from Research Collective, a human factors and user experience consultancy. In this episode they discuss how to integrate human factors into design controls to reduce risk and improve patient outcomes.

LISTEN NOW:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some highlights of this episode include:

- Research Collective helps design medical devices that are easy to learn and efficient to use to reduce risk and improve patient outcomes.

- Product development involves experts and scientific knowledge about how people work, make decisions, and learn to reduce risk.

- Human factors is defined as area that applies all human sciences to design of products and processes.

- Usability consists of four components: easy to learn, efficient to use, memorability, and subjective satisfaction.

- Human factors (above the neck) and ergonomics (below the neck) are one and the same, but have slightly different connotations.

- Best practices for human factors include understanding, testing, and evaluating user needs, capabilities, and limitations.

- Class II and III (some Class I) products require usability testing that includes observation. Design input should be objective and measurable.

- Victory Lap: Validation usability study should represent culmination of work completed to make sure people can use the product.

Links:

Regulatory Affairs Professionals Society (RAPS)

Ultimate Guide to Design Controls for Medical Device Companies

Human Factors and Medical Devices (FDA Guidance)

MedTech True Quality Stories Podcast

Greenlight Guru True Quality Roadshow 2019

Memorable quotes from this episode:

“We’re particularly interested in designing medical devices that are easy to learn and efficient to use to reduce use error...leads to better patient outcomes.” Russ Branaghan

“To be serious about reducing risk, then we need to know some of the scientific knowledge...about how people work, how they make decisions, how they learn.” Russ Branaghan

“If we can integrate that into our design, then we’re doing a good job. Good intentions aren’t enough.” Russ Branaghan

“If you’re designing a product just because you’re trying to satisfy a regulation, you’ve kind of missed the point. Factor those humans into this equation.” Jon Speer

Transcription:

Announcer: Welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast, where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Jon Speer: All right, so I think one topic that has a tendency to create a lot of confusion for folks in the industry these days is human factors. And maybe more importantly, the relationship between human factors and design controls. Well, good news. I have a couple of experts on this episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast to dive into some of those details. I have Russ Branaghan and Bryant Foster from Research Collective, and we dive into the relationship between human factors and design controls.

Jon Speer: Hello, and welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast. This is your host, the founder and VP of Quality and Regulatory at Greenlight Guru, Jon Speer. I'm really looking forward to this conversation because we've talked about human factors in the past, we've talked about design controls in the past, and risk management and all these sorts of things, and sometimes I think about... There's a Venn diagram, if you look at risk and design control on human factors, there's certainly a relationship between these topics. Some might even say they're all the same thing, I don't know; we'll dive into that. But the good news is, I've got a couple of experts joining us on the episode today. I have Russ Branaghan. Russ is the President and Chief Scientist at Research Collective, and I have his colleague, Bryant Foster. Bryant is the VP of Human Factors and User Experience at Research Collective. Gentlemen, welcome.

Russ Branaghan: Well, thank you. Good to be here.

Jon Speer: Awesome. So, I thought we would dive in today and talk a little bit about human factors and design controls. Does that sound okay with you, guys? I know that you live this everyday, so I figured you'd have a lot to contribute on this.

Russ Branaghan: Absolutely. One of our favorite topics.

Jon Speer: And of course at some point I wanna... The folks... And maybe now is actually a good time. Russ or Bryant, one of you, do you mind maybe giving a 30-second overview of what Research Collective is all about, and what you do, and how you help companies?

Russ Branaghan: Absolutely. So we're a human factors and user experience consultancy. Majority of our work is in medical devices, and we're particularly interested in designing medical devices that are easy to learn and efficient to use, and satisfying and so forth, but the real benefit of that is, it has a tendency to reduce use error and as a result leads to better patient outcomes, fewer difficulties using the device, more efficient medicine, and so on. So in that way it really does relate to risk and risk reduction.

Jon Speer: Yeah, absolutely.

Russ Branaghan: The idea is we do things to reduce risk, and the human is probably the most complex part of that, and that's where we focus.

Jon Speer: That's terrific. So let's just dive right in. There's a couple of things. I've been in this industry now for over 20 years, and I started my career, as most listeners have probably picked up by now, as a product development engineer, and I always... I guess as a product development engineer, I always thought about or considered that there are gonna be humans using the products that I'm designing and developing. So I guess I'm a little curious from your perspective, why do we pay so much attention to human factors in 2019?

Russ Branaghan: Well, for me I think a couple of things. You mentioned product development and what goes into it. And typically in product development you have experts in all kinds of areas, so you'll have experts in mechanics and electronics and marketing and accounting, and all of these kinds of things. But interestingly, the people who use the product are human beings, and the people who buy the product or make decisions to buy the product are human beings, and we're using them on human beings. But interestingly in these product development processes, you rarely have people who have decided to study human beings for a living, and there's an awful lot to know about people, about human beings. And it's important that we're just as rigorous in studying these folks and designing for these folks as we are in getting the mechanics and the electronics and so forth correct. So that's kind of the idea is, "Boy, if we're really going to be serious about reducing risk, then we need to know some of the scientific knowledge that's out there about how people work, how they make decisions, how they learn, and so forth. And if we can integrate that into our design, then we're doing a good job."

Russ Branaghan: But the issue is that just good intentions aren't enough. So there's plenty of folks that become very interested in doing this, and I applaud them for doing that, but they don't usually have the training and, frankly, years of studying folks in the lab and in context. So it would be sort of like deciding that, "Well, you know, I've really become interested in mechanics recently so I'm gonna become a mechanic. I'm gonna start doing mechanical engineering work." The notion is that, "Sure, absolutely, go do that." But it typically requires an awful lot of training and awful lot of background. And I think that's our job is to be as expert as possible at that, and as rigorous as possible at that.

Jon Speer: Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. Bryant, anything that you would contribute to that?

Bryant Foster: No, I think at its core... One of the things I like about your podcast and hearing you speak in several occasions is the notion that the regulations are great, and it's nice that someone cares enough to put a regulation in place, but at its core we're designing things ultimately to help people, and that's especially true of medical devices. And so when we talk about design input... Or, I'm sorry, design controls and human factors, at their core they really are intended to make things better, safer and more effective for the people that will benefit from them. And so I think as this discussion goes along, we'll talk about how these two, how human factors dovetails into the design process and the design control regulation.

Jon Speer: Yeah, I love that. I think that's sort of a key point number one, and I'm sure we'll uncover maybe a few others in our conversation today. But key point number one, folks, if you're designing a product just because you're trying to satisfy a regulation, you kinda missed the point. [chuckle] And to Russ' and Bryant's point, humans are involved with the products that we're designing and developing so we have to certainly factor those humans into this equation, and that's part and parcel why we're chatting today. And maybe it's a little obvious, but maybe not. So I guess folks, two experts on the call today from Research Collective, Bryant and Russ. Gentleman, how would you define human factors? Maybe give us an interpretation of what this includes, maybe what it doesn't include.

Russ Branaghan: Yeah, so there actually is a... There are several very good definitions, but the idea is human factors is the area that applies all the human sciences. So what we mean by human sciences is that includes all of the "ologies", like sociology, psychology, physiology, etcetera; applying that to the design of products, also the design of processes and training material, and so forth. It also includes the application of the medical field, and so on, but the idea is to take the knowledge that's out there about those areas, studying human beings and applying it to product design. So there's really two components to it, there's an evaluation component where we've got a product and we're off trying to figure out, "Boy, how well does this work? What kinds of mistakes do people make? How do we fix that?" But there's also the component that's focused on design, which is understanding not only how to design something but, "Boy, what should we be designing to begin with? What are the hassles that people have? What are the needs they have? And so forth. What kinds of problems are they having in their day-to-day life?" So it ends up being kind of an activity that's involved from the beginning to the end and having those two components which is evaluation and design.

Jon Speer: All right, that makes a lot of sense. Now, I think there's, sometimes there's terminology confusion and I'm glad you set it straight on the human factor side of things, but there's a couple other terms that sometimes enter the lexicon I think, at least they have over the past several years, that may relate to human factors. So I wanna get your take on this. So the two terms are usability, and I know we're gonna talk, or I plan to talk a little bit about usability with respect to human factors here in a bit, but usability oftentimes comes up. Another term that comes up, I think, in this general topic is ergonomics. So, can you maybe spend a moment and compare and contrast human factors versus usability versus ergonomics? Are these the same thing? Are they different things?

Russ Branaghan: They're so related that they're almost synonymous. I can give you some background in usability. Usability is really, has just a few components. So a usable system is something that's easy to learn, once you learn it, it's efficient to use, it tends to be memorable so that if you went away on vacation and then came back and had to use the device again, you remember how to use it, you don't have to get up to speed again. And then finally, it's, frankly, it's satisfying. It's one of these things that you don't mind using. So those are the four components: Ease of learning, efficiency of use, memorability, and subjective satisfaction, they call it. And a fellow named Jacob Nielson sort of identified these things about 25 years ago.

Russ Branaghan: Human factors and ergonomics interestingly are the same things. So, typically in Europe, they refer to it as ergonomics. In the US, they refer to it as human factors but they're the same things. Now, they do have slightly different connotations for some reason, but the fact is, the slightly different connotations are that ergonomics often refers to things that happen below the neck, so kind of physical kinds of aspects and human factors tend to happen above the neck, that is, cognitive types of things but those are just connotations. The actual fact is, they're really the same things, it's just a geographic difference.

Jon Speer: Well, that's good to know. I didn't realize the above the neck/below the neck notion but that's interesting. All right, so you guys deal a lot with all kinds of devices, all types of products, and that sort of thing. And I guess you probably have some best practices or some advice on to when to get involved from a human factors perspective. Is it too early? Is it too late? Give us a little bit of context as to when human factors should be involved in product design and development efforts.

Bryant Foster: Sure, so the easy answer would be as early as possible, but I'll explain a little bit about what I mean by that. Being that we're talking about design controls and human factors together, I'll refer back to the design controls, and the first part of the design control regulation is understanding user needs. And as Russ has talked about, all of what we do as human factors practitioners is think about the users. And so I feel like we're really good at helping manufacturers or people with ideas for medical devices understand more and have a better and deeper understanding of their users, which includes who they are, what their training includes, what kinds of limitations they might have and capabilities, also things like the environment in which they work, or maybe there's multiple environments because all of those things will really influence and impact how that team or group goes about designing their product.

Bryant Foster: So we can do that early on and we do that through sometimes observations, so going out into the context of use, and seeing people actually using a product, maybe a predicate device or just seeing people in their natural habitat and feeding that back into things we might know about the design. For example, if someone is using a product at home, we might design it much differently than we would if we were designing something to be used in a hospital. So, knowing those things ahead of time can set the design off on a course that is meeting those user needs right up from the front. And then throughout the process, as the device continues to be developed, we would check back in with those users, with those people who would be using the product, and seeing if the product that we're making is actually meeting those needs that we identified in the beginning.

Bryant Foster: And that's where we'll get into another term, formative usability testing or just formative evaluation, those come into play there because we now have something physical, a prototype of some sort that we can take out and put it in front of the people who might be using it, have them actually perform real tasks that they might need to perform once the device is completed and see where it meets their needs and maybe where it doesn't, and to give those... Provide those design recommendations back into the design so that we can align it better with those user needs and make sure that we're continuing on the process of creating a product that indeed is usable and meets the needs of the users.

Jon Speer: Yeah. That's a really good overview. And I think this is one of the areas where I've seen, in my experience, a lot of companies really struggle especially with that user needs stage. I mean, I think historically, that user needs almost is not given the proper due diligence or the proper attention during design and development. I think there's a lot of times engineers wanna rush into and start defining specific design input requirements, but I think it's... You hit on a couple of points. You talked about the extremes or some extremes were home use versus in a controlled environment type of setting. Those are sort of obvious things, but I mean, how much emphasis would you put on the importance of user needs? It seems like it'd be pretty important regardless of the type of device.

Russ Branaghan: Yeah, it's absolutely critical. If you think about what we're trying to do here, our work should be generally evidence-based. So we're off trying to figure out, "Okay, what's the evidence for various types of design decisions?" And the evidence of those things are actually in the context of use. So if you understand your users and their tasks and what they're trying to do, their goals and so forth, really, there's an infinite number of products one could design, as long as you understand your users well enough. But I think instead what ends up happening is, it's still often technologically driven, and we think, "Okay, what can we do with this technology?" And we sort of dream it up, and then we work backwards to figure out, "Hey, is it possible anybody really wants this? Is it possible that anybody can use this?" And it really does put the cart before the horse as opposed to understanding people's needs really deeply and then thinking about, "Well, boy, if we really knew this population, if we really knew their tasks, if we really knew their chores or their tasks inside and out, then frankly, we could develop a whole number of things to make their lives a lot easier."

Jon Speer: I love that notion because I think... I was talking to a customer earlier today, catching up with where they were in their product development journey, and they talked about they're on... I think they said their 10th or 11th iteration or prototype of their product. And I think that's really a key to understand that user needs can help you identify a litany of possibilities. Whereas, if you don't give it the due diligence and the proper focus early on in a project, you kind of paint yourself in a corner.

Russ Branaghan: That's exactly right. And I think that's one of the things Bryant was saying early on, the sooner we get involved, the better. So if you think about how this works, early on in the design, you can entertain really any number of alternatives, and if you make any one change, well, it hardly costs a thing when it's early. [chuckle] But as you start making decisions and get down the product development process, as you said you paint yourself into a corner with each successive decision. And now, if you start making changes, well, it starts getting to be more expensive, and towards the end, if it's close to product release time, you can make very few changes, so you start doing things like, "Oh, we'll include... We'll improve the instructions for use, for example, so that people know how to use it." And if you make any change to the product, I mean it is just prohibitive, and it's certainly not something you wanna start telling your management about to say, "Hey, you know what? I probably should have recognized that the products should have different characteristics to begin with."

Jon Speer: That's a really good tip. And folks, I always... When I talk about... You think about design or coach people on design controls and how to manage this process, if you will, when you get into user needs, it's good to think about those options, but you have to think about from a overall design and development perspective, eventually, at some point in time before you go to market, you need to demonstrate that your product meets those needs of the end user. And so, putting the weight on that is really key. And so you gotta think ahead. You gotta think about if these are the specific user needs, how we're going to prove or demonstrate that at some point, not just for the sake of checking a box on a form, but you need to have the objective evidence to show that your product works and meets those needs of the end user that you've designed the correct product to solve whatever challenge it is that you set out to do to begin with. So, it's really important to be forward-thinking when you're defining this.

Jon Speer: Folks, I wanna remind you all, I'm talking with two experts on human factors. I'm talking with Russ Branaghan, he's the President and Chief Scientist at Research Collective, and his colleague Bryant Foster. Bryant is the VP of Human Factors and User Experience at Research Collective. You can learn a whole bunch more about what they're doing and how to interact and work with them, and then engage them early and often throughout your design and development efforts. Simply go to www.research-collective.com to learn more. While I have this quick break, I wanna remind you all that... Did you know that Greenlight Guru, we recently launched a brand new podcast? Yep, that's right. We have a new podcast, it's called MedTech True Quality Stories. I'm loving this new flavor, if you will. We are talking with medical device professionals, folks that are in the trenches, executives, product developers, and so on, and learning some of their true quality stories, some of the things that they've been faced with and how they've overcome those things in order to bring new exciting products to market.

Jon Speer: So wherever you're listening to this podcast, you'll be able to also find MedTech True Quality Stories. Yep, it's on iTunes, it's on SoundCloud, everywhere else that you might be listening to podcasts. You wanna go check that out, it's really exciting. So share that with your colleagues and your friends and love hearing these stories. So be sure to check that out. Alright, so gentlemen, let's get back to this. Let's talk a little bit about... Still on the human factors realm, but let's explore a little bit more in-depth. Let's go into usability testing and let's get a better understanding for what that's all about and when does that apply. So what types of products or devices would require usability testing?

Bryant Foster: So in terms of FDA, you're gonna have your Class II and Class III products that are going to require human factors testing and they kind of matches up with the same requirements for design control so there's a few Class I products in there as well. And usability testing, as we mentioned early on, not only is it a regulation and something that is going to be required, but it is just helpful to see people using the product before you launch them. There's so many things we learn through usability tests when we see people actually using the product that are pretty eye-opening a lot of times to the product team. And I want to make reference to the ultimate guide to design controls that Jon, you posted, I think last year, maybe a year before on your website, and I was looking at that in preparation for this, and one of the things you have when we talk about making the decisions for what to design, that would fall into the design input category of design controls. And you say, and I totally agree with this, that design input should be objective and measurable. So often we'll see design inputs that say things like, "Okay, our product needs to be easy to use." Well, how do you define that, and what does that actually mean?

Bryant Foster: I think a better design input would be something like, people need to make this connection in three seconds or less because there's some implication if they don't, and that would be measurable. And then through a usability study, we can actually measure this before we go to market. So the only way to really check to see if our design inputs are being met is actually observing the people performing those tasks. So there's the formative as I mentioned before, formative studies where we're still in the process of designing and refining, perfecting the product, ultimately leading to what the FDA would actually require, which is the validation usability study. And the validation usability study should represent a culmination of the usability work that you've done along the way to make sure that people can use the product.

Bryant Foster: We like to say that the validation study should be more of a victory lap than anything else, but often it's not that way. Most of the time, it seems like the groups are going in hoping that, "Okay, that we've designed this product, we thought about our users, we made it usable," and then they go in the validation study and they're surprised by the results that aren't as positive as they would hope and might cause them not to actually be able to get approved or cleared.

Jon Speer: And can I... Do you mind if I interject here for a moment?

Bryant Foster: Not at all.

Jon Speer: That last comment I think is really important because in my experience in observing what people do and how they embrace human factors, it seems to me that there's an overwhelming, or a large percentage [chuckle] of companies or product development projects where the first time they formally think about human factors is at this usability stage. And you hit on something I think is really important; it should be the victory lap, so to speak, it shouldn't be any surprises, but a lot of times this is where I see companies where they first think about human factors is when they realize, "Oh wow, we have to do some usability."

Bryant Foster: Yeah. And when I think about human factors, it fits into the performance data that's going to be required for the submission and you wouldn't get to the very end and then try to do a clinical study to determine if your product is effective. You would wanna make sure that that is done well ahead of time because if it turns out that it isn't, then you can make adjustments and ensure that it is before you get to launch. And I think human factors really should be thought of in the same way you wanna make sure that people can use the product well ahead of your design freeze, because once you've frozen the design and you're ready to go to market, if your human factors or usability testing identified some issues, it's really hard to go back and make those changes.

Jon Speer: Yeah, for sure. That's really good insight. So I guess I'm a little bit curious, and obviously at Research Collective, you do all things human factors-related, correct? You're not just particularly... And I think you have to be to be an expert in human factors, you have to be kind of full stack, so to speak, right?

Russ Branaghan: Yeah, that's exactly right. So the idea from our group is we've decided to focus solely on human factors, and as a result, we've gone off and gotten some awfully good specialists in this area; they typically have master's or doctoral degrees in human factors, or sometimes what's called Human Systems Engineering, which is more of a recent term for human factors. But yeah, that's their life's chosen work.

Jon Speer: And I gotta imagine you've got your finger on the pulse as to where one might go to learn more about human factors. I'm sure your website has a ton of invaluable information, but what are some other sources that people can check out to learn more about human factors?

Bryant Foster: Yeah. Great question. So we do have information on our website and we keep a blog that we post to pretty regularly, I'm trying to... Again, like you mentioned, the finger on the pulse of human factors. I think there's great documents out there that people can access for free, and these are... So I'll just mention the FDA Human Factors Guidance, which is titled Applying Human Factors and Usability Engineering to Medical Devices. And then for international standards, the document is IEC 62366, and there's a 62366-1, which is the standard, and then a technical report 62366-2 that explains some of the early research that can be done to... More of the formative research that you can do as you're designing the product. But again, these are what I like to think of... If you think of it like the a high jump, they're kind of the low bar.

Bryant Foster: And unfortunately, I think what they do sometimes is they convey what the lowest requirement is which is passing this validation test at the very end. But I think what happens is when manufacturers shoot for that, they come up a little short. And so, implementing... So understanding that that is the ultimate goal by applying some of these things like we talked about, understanding the user needs a little bit deeper, doing formative evaluations to make sure the product meets those user needs along the way can make sure that when you do get to that final hurdle of the validation study or validation usability study, that you actually can clear it.

Russ Branaghan: Yep. I should also mention in the category of shameless plug, we also offer classes on human factors and so forth. And of course, we'd be happy to provide those for people who are interested.

Jon Speer: Oh, I'm glad you mentioned that, because I don't think it's a shameless plug at all. I think it's wonderful, because this is a topic that there's... It could be overwhelming. I mean, Bryant, I'm glad you mentioned the FDA guidance and the IEC standard. I mean, those... To your point, I mean it's kind of minimum expected behavior, so to speak. And folks, keep in mind that the guidance documents and standards, while helpful, they are snapshots in time, and that time was years ago, many times. So it doesn't always reflect the latest, greatest, best practices and thinking on the topic. So this is why a resource like Research Collective is so invaluable for you to keep in mind because they know where this... They're experts, number one, and second, they know where things are moving and they're adapting their practices, their solution offering to keep you, not only in line with from a regulatory perspective, but what's important to your patients and to the users and to the humans who are gonna be using and interacting with your products. So be sure to check that out. In fact, Bryant, I think I recall that you've got a training course coming up sometime later this year on the topic, right? Tell us a little bit about that.

Russ Branaghan: Sure. So I have gotten involved in RAPS, the Regulatory Affairs Professionals Society over the last couple of years, trying to round out my regulatory knowledge, 'cause again, as Russ mentioned, I come to this focused more on human factors, but within medical devices, it's important for us to understand the regulatory landscape. And so as I've gotten involved in that, I've talked to the training group there and they've agreed to have a design controls and human factors course that will be done this summer. So I'll be teaching that along with a regulatory consultant named Margaret Koga, and that is going to be August 28th and 29th in Southern California. I think it's Costa Mesa, to be exact.

Jon Speer: Okay. And that's an in-person session, correct?

Bryant Foster: Correct. Yep, 30 seats. It's not on their website yet, but I expect to see it up there on their calendar soon.

Jon Speer: Alright. And folks can, in the meantime before it gets published, they can reach out to you directly, I'm sure, to learn more about that?

Bryant Foster: Absolutely.

Jon Speer: Alright, folks, connect with Bryant Foster. You can go to research-collective.com to learn how to get in touch with them. I know they have a contact page, you can reach out to them. His email... I'll just... Okay, I'll share your email, Bryant. [chuckle]

Bryant Foster: Sure.

Jon Speer: Alright, it's Bryant, B-R-Y-A-N-T at research-collective.com. If you're interested in that course or any of the other courses, feel free to reach out to Bryant and learn how and where and when to sign up and all those sorts of things. So, I guess just a couple more things I wanted to explore a little bit while we have a few minutes left on this episode. So I guess being, I guess somewhat of a devil's advocate, so to speak, can I just do the human factors testing all by myself? Why do I need you? Why do I need to involve others? Why can't I just do this myself?

Russ Branaghan: Yeah, it is a great question. And I think people are often interested in doing this to save money and so forth. But I think it's like a lot of things, at least the first time... And you can do it, to some degree, yourself. The first time you're trying anything new, we have a tendency to sort of stumble through that thing. There's always a learning curve on everything we do. And as you're doing that, I mean it's a terribly inefficient process and you run risks, so risks of doing it wrong, risks of making mistakes and so forth. And these are things that you're running off and submitting to FDA. So in that sense, it increases your risk, it increases the amount of time and expense that you spend on it personally. It's not that it's free, simply because you're doing it yourself. You personally are worth a fair amount of money in terms of your regular work.

Russ Branaghan: So in that sense, it's sort of like going to a specialist at least the first time or a second time through. Because working with us, for example, you end up learning an awful lot about how to do this to begin with, so that maybe the third or fourth time, you can do it yourself. But, at least the first or second times, you're really getting the confidence of knowing that you're doing it right, and I think that matters a lot. So I often think about it as not only getting the work done, but a fair amount of just-in-time training at the same time. So, I'm thrilled that people are pursuing this at all. And regulatory has had a lot to do with that, making sure that people pursue it. So I'm pretty excited about this as a guy who studies, who's been studying human factors for 30 years, that people are interested in it. It's just that, I think for the first few times, it really makes sense to work with a specialist and get the skills under your belt.

Jon Speer: Well, and to your point, you've been doing this 30 years at Research Collective. This is the sole focus of your business, I mean, you're experts. "Yeah, I'm an expert in quality systems, I'm an expert in design controls, and so, it just... We can teach you, we can help with putting some "training wheels" on and teaching you what to do and when to do it." But that first time you're going through this, it could be a little overwhelming. And nothing's worse than getting to the point where you think you're at the end, and you think you're about to cross the finish line, and you're about to go to market and launch, and you get a question back from a regulatory submission like, "What about this, and what about that?" Or you learn during that usability testing that, "Wow, things didn't go so well." Those are not ideal times to find out those types of things.

Russ Branaghan: No, I think the cost of that and the hit to your reputation and just plain old heartache [chuckle] are really too much to risk.

Jon Speer: You talked about it earlier, the cost of making an iteration while you're at that user need stage is a lot more tolerable than being, right before you go to market. I don't know what the official name of this "rule" is, I always refer to it as the 1-10-100. And there's probably some formal name to that. Do you know what it is by chance?

Russ Branaghan: I was just thinking about this. If there's not, there should be.

Jon Speer: Maybe it's called the 1-10-100 rule, I don't know. [chuckle]

Russ Branaghan: Well, it is now. I think you've got it for posterity.

Jon Speer: Well, and let me... You and I, we know what we're talking about, but folks, the 1-10-100 rule, let me paraphrase or summarize this briefly. The notion is that if you are early in development and making a change or an iteration, it's gonna cost you "$1" and a little bit later it'll cost you... Making a change will maybe cost you $10, a little bit later $100, a little bit later $1,000. So it's an... This exponential "rule" that the later the change is made, the more expensive it is because of all the things that are impacted by that. So 1-10-100. I'm sure there's probably some Wikipedia page, or something like that. Go look it up and check it out for yourselves.

Russ Branaghan: Yeah. And believe me, I will go look this up.

[laughter]

Jon Speer: Alright. So, I thought of, kind of one thing to kind of wrap up our conversation today and getting into the details a bit of human factors. Can you combine, and maybe it might make sense to define this a little bit, but can you combine formative studies and validation studies?

Bryant Foster: They really are different things. I think what happens is... This happens to us, we get this question a lot, when the group is coming in at the very end of the game, and they say, "Hey, there's a couple of things we wanna learn about our product, but at the same time, we need to validate it." And so really, they're two different things. The formative studies or evaluations are meant to be done, as I've said, along the way to inform the product design. And really the validation should be its own standalone thing because at that point, we're not... The goal of the validation study is not to learn any more, it is to demonstrate through evidence that people can use this product effectively. So they really can't.

Russ Branaghan: Yeah. In fact, I... Yeah, good. I was gonna say it even stronger, absolutely not. They really need to be different things, their purpose is different. What we're trying to do in these formative studies is kind of ferret out all of the usability problems that we can find so that they can be fixed. So pretty straightforward, if you think about it as bench-top testing in other areas and so forth. But yeah, that validation has to be one where we're actually demonstrating that this is not going to likely cause any undue risk... I'm sorry, use errors and so on. And under the best, in fact, I had never heard this phrase or Bryant used this phrase, but what we're shooting for and under the best of circumstances, is it's a victory lap. In other words, we've gone through this and you've got confidence going into it. And I've got to tell you, it's a completely different experience when you've got confidence going into a validation test than when you don't.

Jon Speer: Oh, for sure.

Russ Branaghan: One's very enjoyable and the other is anything but.

Jon Speer: Absolutely. I've been there, done that on both sides, sadly. But yeah, I can totally relate. So, gentlemen, I know we're just skimming the surface of human factors, but I appreciate you taking time to enlighten us a bit about what's important about human factors. And I tell you what, maybe we can have some additional sessions and episodes where we dive a little bit deeper in some of the nuances of human factors, if that's okay with you?

Russ Branaghan: Oh, we'd be thrilled. Absolutely.

Jon Speer: Alright, folks, I wanna remind you I've been talking with Russ Branaghan, President and Chief Scientist, and Bryant Foster, VP of Human Factors and User Experience. Both are with Research Collective, research-collective.com. Go check out what they're doing and reach out to them and connect with them, they're happy to help you along this... In your med device journey. Speaking of, have you checked out or heard about the Greenlight Guru, True Quality Roadshow? Yep, that's right, there's a good chance that we're gonna be coming to a city near you. So far, stops have included Indianapolis, Atlanta and Boston. And in fact, our friends at Research Collective will be joining us at two of the upcoming roadshows later this year in San Francisco, as well as in San Diego. So, go check that out. You can just type in Greenlight Guru Roadshow, and you'll get the link to the page and you can sign up. We're gonna be visiting Houston, Minneapolis, Orange County, San Diego, San Francisco, and probably quite a few other cities into 2020 as well. So, go check that out.

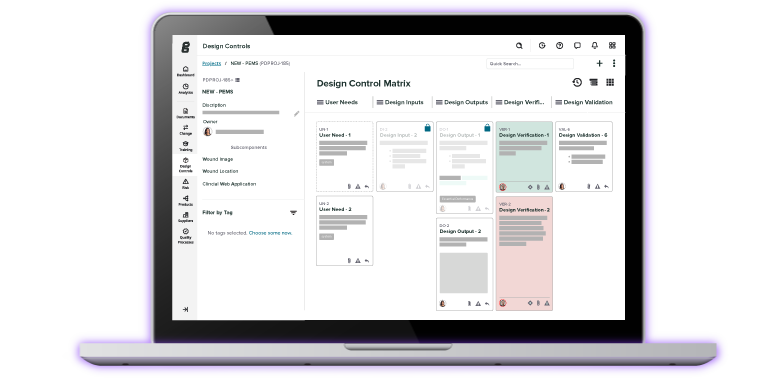

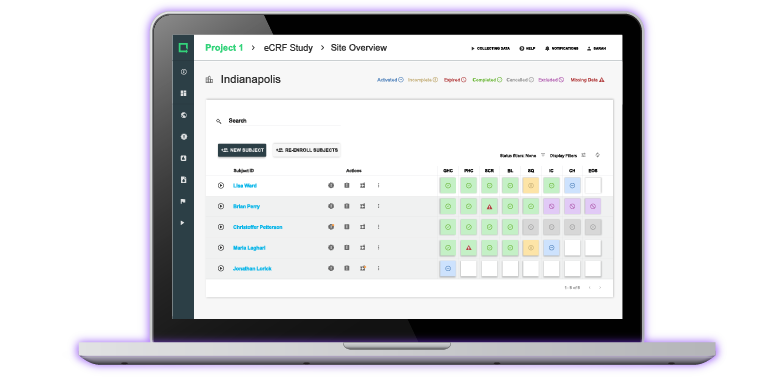

Jon Speer: Folks, thanks as always for listening to the Global Medical Device Podcast. As you know, Greenlight Guru is here to help you improve the quality of life, help you get products to market faster, that are safer, that are minimized from a risk perspective. We're all about making sure those humans know what to do when they get your product and that it's gonna make a difference. So along the way, you're gonna be dealing with your quality system, your design controls, your risk, hopefully not, but maybe some CAPAs and some customer feedback. We've built an eQMS platform specifically and exclusively for the medical device industry. So be sure to go check us out if you're interested in learning more about how we can help. Go to www.greenlight.guru to learn more, and we'd be happy to have a conversation with you. As always, this is your host, the Founder and VP of Quality and Regulatory at Greenlight Guru, Jon Speer. And you have been listening to the Global Medical Device Podcast.

ABOUT THE GLOBAL MEDICAL DEVICE PODCAST:

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Nick Tippmann is an experienced marketing professional lauded by colleagues, peers, and medical device professionals alike for his strategic contributions to Greenlight Guru from the time of the company’s inception. Previous to Greenlight Guru, he co-founded and led a media and event production company that was later...