When should you begin to consider human factors with your medical device design and development efforts? There are some simple and straightforward actions to assess human factors needs sooner than later.

Today’s guest is Mary Beth Privitera, principal - human factors at HS Design. She explains how it is a bit of a conundrum to know how and when to implement human factors because of standards and guidelines that create confusion. But don’t be afraid! Continue to develop products that improve people’s quality of life.

LISTEN NOW:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some highlights of this episode include:

-

Everyone wants a product that’s easy to use. The problem that arises is how to define and measure such a requirement.

-

Start human factors immediately. What will make the medical device safe and effective for real patients under real conditions of use?

-

Capture user needs by asking carefully crafted questions. Don’t ask loaded questions to lead users to answers. Know your user and use environment.

-

To avoid confusion, understand the definition and differences between use error (preventable by user and/or manufacturer) and user error (fault of user).

-

Waterfall vs. agile process regarding human factors. Use an iterative process; it’s not a checkbox exercise.

-

User interface includes the labeling, packaging, and other standard design elements that generate interaction between a user and the device.

-

Understand user needs to structure design and development for verification and validation of designing the correct product and the product correctly.

-

Why do some break the rules and not follow protocol? Pros and cons of a strong human factors program include foreseeable and unexpected uses and risks.

Links:

Mary Beth Privitera on LinkedIn

FDA Human Factors Considerations (Medical Devices)

Memorable quotes by Mary Beth Privitera:

“It is a bit of a conundrum in terms of which way do we go with human factors.”

“At the end of the day, everyone wants to have a product that’s easy to use.”

“A user need is human factors. You’re talking to a human. They have a need.”

Transcription:

Announcer: Welcome to the Global Medical Device podcast, where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Jon Speer: When in the world should I start human factors with my medical device design and development efforts? It's a big question. It's a hard question. Well, I think we make it harder than it needs to be, quite frankly. And I think you'll find out there are some simple things that you should be doing and are relatively simple and straightforward for you to be doing to assess human factors needs fairly early on in a project, and to help answer some of these questions on human factors, enjoy listening to this episode of the Global Medical Device podcast, where I have human factors expert Mary Beth Privitera from HS Design.

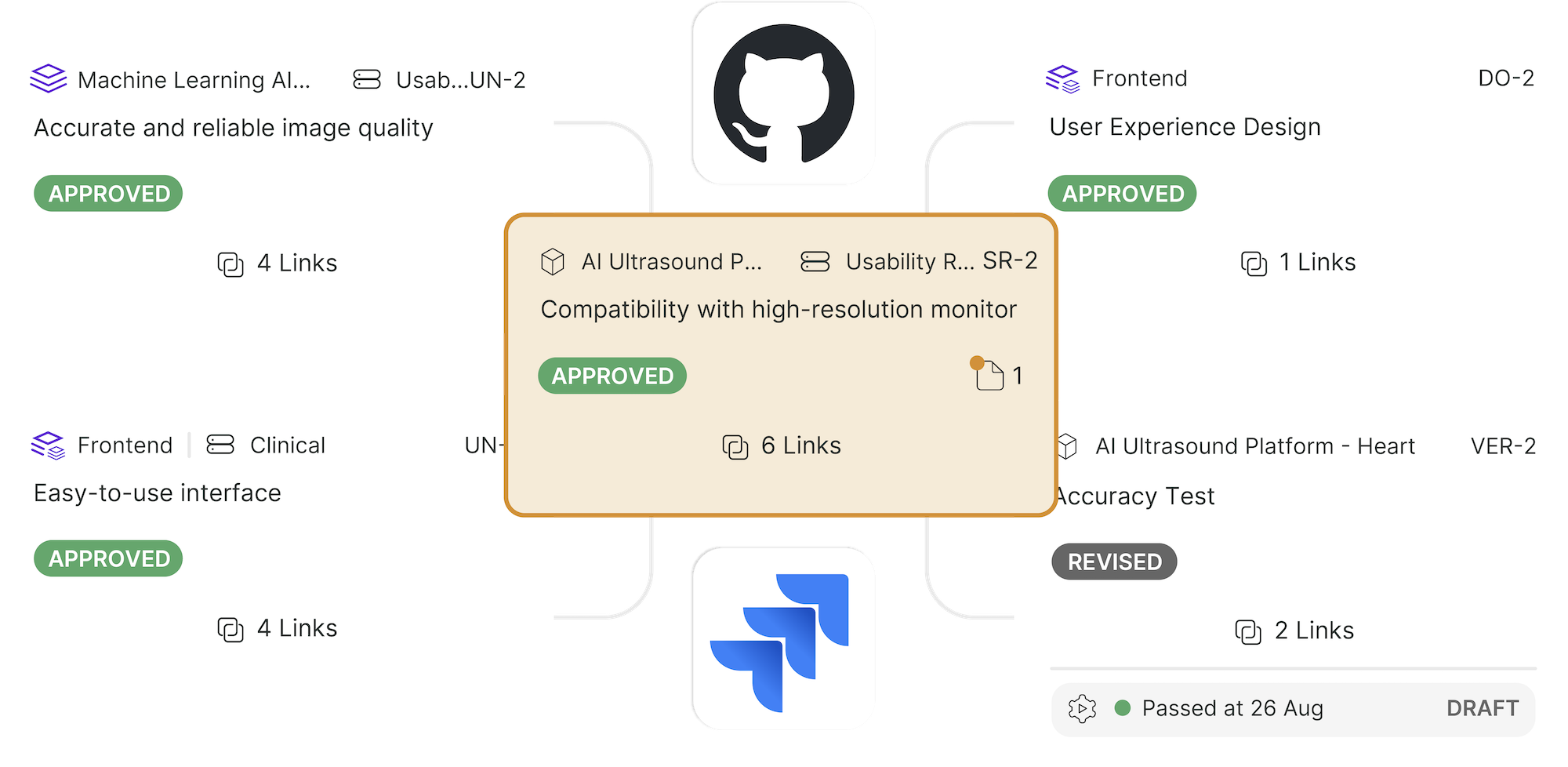

Jon Speer: Hello and welcome to the Global Medical Device podcast. This is your host, founder and VP of Quality and Regulatory at Greenlight Guru, Jon Speer. And this topic of human factors, I'm just gonna confess, folks, it's confusing to people. And I don't know if there's good reasons as to why. I think there's this Johari or Venn diagram between design controls, and risk, and human factors. Maybe it's just a complete circle, maybe they're all the same thing. But of course, that's debatable, and it makes for good conversation. And with me today, I have, really, an expert in human factors, Mary Beth Privitera. She is principal of research in human factors at HS Design. Mary Beth, welcome.

Mary Beth Privitera: Thank you, Jon. I'm excited to be back and looking forward to this discussion, because you're right. It is a bit of a conundrum, in terms of which way do we go with human factors.

Jon Speer: Yeah. And I wanna kind of explore that. And so, today, I thought we could talk about when to start human factors. But I guess, before we get into that part of the topic, why do you think there's such a conundrum on this?

Mary Beth Privitera: Well, I think part of it is that there's lots of standards and guidances out there. The field of human factors in and of itself is an enormous field. It goes anything from the automotive industry to the aircraft industry. And really, it wasn't until the pentacle article of To Err is Human, in the Institute of Medicine's article back in the late '90s, early 2000s, that this became something that was really a focus area of medical devices. And since then, there's been lots of publications, lots of guidances that have come out recently, international guidances. And I think that there's just... It's a change of practice. You're right about the Venn diagram. I completely agree with you that there is a Venn diagram that does... That it's integrated in here with risk, and design control, and quality. Because at the end of the day, everyone wants to have a product that's easy to use. I don't know of any device design project I've ever been associated with in any form, be it at university or professionally, that doesn't have ease of use as a requirement. The problem becomes is, how do you define it, how do you measure it? 'Cause it's not as if you can measure it readily. And so I think that's part of the issue.

Jon Speer: Yeah. To me, it was always just part of being a good engineer. And along the way, I think you mentioned standards, and some regulations here and there, and so on and so forth, that have evolved over time. And it seems like a lot of times, the rules, if you will, formulate because of things that didn't go so well or people that... Or products that didn't come up to snuff, or there were some sort of adverse event or some sort of issue, which is unfortunate, of course. And I think we're at a point today, at least from my lens, looking at what's going on in the industry where there seems to be a convergence of these things. Again, I think the way I think they should be. But I guess, from your human factors lens looking at the world, let's talk a little bit about when to start human factors with respect to the design and development of a medical device. I guess, that's an open-ended question. When do you start, Mary Beth?

Mary Beth Privitera: [chuckle] Well, yes. Great question. I'm gonna say that you start immediately. I think once you have an idea of where you're gonna go, of what direction you're gonna head... In other words, you have an idea of what type of product design, you can really get into what are the attributes that are going to make this device safe and effective in the hands of real users under real conditions of use. You could also state that the human factor starts even before you have an idea. The contextual inquiry process does help in generating ideas. And if you look at Stanford's Biodesign program, they are looking at need finding and identifying what those are. And a user need is human factors. You're talking to a human. They have a need, so user need is human factors. That's where I say you should start it off immediately.

Mary Beth Privitera: And I think once you have an idea, though, that's where you really can take a look at... When I just take the definition of in the hands of real users, you can get into the who are your users, what are their attributes in terms of their education, their capabilities, their physical capabilities, their mental capacities, and how is this life of the device going to be used? And that gets into the what are the real conditions of use? Are they gonna be using it in their car, at home, at work? Is it in the hospital? Is it something that's gonna require a lot of training, or is it something that is decision-making, decided to be used by a physician, but really used by a tech. And those are where I think things get lost in the muddle and it becomes very, very confusing for people to implement their human factors.

Jon Speer: Yeah. And when you say immediately, I think... Well, I guess I don't know what the perceptions of our listeners are. I could tell you my perception is, it's probably the wrong perception, so you can level set, and correct my line of thinking on this. [chuckle] But when you say immediately, I'm like... I expect... I scream a little on the inside, like, "Oh, my goodness. That seems so painful. Why would I start formal human factors activities immediately just because I have a design?" And I think, just to elaborate a little bit of what's going on in my head, a dangerous place at times, I know. But what I'm thinking is like, "Oh, do I have to formalize a plan, and start to document all these things immediately? That seems too soon to do that. But I don't think that's what you're suggesting when you say, "Start human factors immediately," right?

Mary Beth Privitera: Well, I'm happy that you're afraid of that, that it scares you that you're thinking, "Oh, my God. It's gonna become burdening stuff. This is... " That's so funny because you're actually doing it anyway. And I think that's part of the confusion, is that, again, you've got user need in that first block on design control. Well, your user need is the human factors need. That's what they need from the performance of the device to do. And so it's just a matter of elaborating that into, have empathy for that user. It's something that... And I think that's part of the issue is that because it's not been integrated in our everyday life in terms of, "That's just something that you do." For example, would you consider sending out a drawing that didn't have tolerancing to a manufacturer? No. Well, did you consider that a user was gonna use the device, and if they're going to like it or not like it? Well, we did. We want them to like it 'cause that improves our market share. Those are the essences where I can bring in, "Yes, they like it," that's a human factor. That's an opinion and opinion is part of their needs. Does it meet my need? Do I enjoy doing it? You're kind of already doing it anyways, although you don't know it. And then in regards to the, "Do you need a formal strategy?" How often is it that we do a formal strategy of something, and it works out exactly how as we planned?

Jon Speer: Yeah.

Mary Beth Privitera: No, I don't think... [chuckle] I don't know that that's a...

Jon Speer: No, it's a good point. And I think that's a good point of emphasis. This is maybe where that Venn diagram overlaps a little bit. I like that idea. You're right. I should be capturing user needs now. I think the thing that I've observed a lot from companies is that maybe they're not doing as good a job of capturing user needs toward the beginning of a project. And maybe that's where we can tighten up our practices a little bit. There is that need. And think about it, folks, downstream, you're going to be demonstrating that your product meets the needs of the end user. And how can you possibly do that if you didn't define what those user needs are somewhere in that project, right?

Mary Beth Privitera: Yeah. It gets down to... I think there is overlap. I think human factors is this wonderful overlap between what does your marketing department need in order to promote sales? What do your engineers need to demonstrate clinical efficacy? And then... And that's the ageless saying, "Well, show it to me. Show me that you've reduced your risk, and one of the risks being you there." How can I demonstrate that? And oftentimes, I find, while we're doing human factors studies, the marketing department might be shoulder burning saying, "Well, how can I develop my story around this that demonstrates that this is going... That this really, truly is the best thing since sliced bread, or that it really is easy to use?"

Jon Speer: Yeah, okay. So capture user needs, I know there's a little bit of art to all of this, certainly some science and some technical ability, but there is a fair amount of art. And so, I guess, curious. What advice do you have to those listening to capture user needs in a way that's meaningful. Do you have any tips or pointers on that topic?

Mary Beth Privitera: Yeah. I think the art gets down to the questions, and how you phrase the questions to your users, and how you get the information and document the information. Oftentimes, what I hear is that they've led the user to an answer. And whenever we're leading the user to an answer and we're asking loaded questions, we really aren't letting the user be the user, or the technology is so cool that the user we're talking to is just in love with it. And they're contorting their body, and they're really working hard to use the device, and they're excited by it. They don't say anything bad because inherently, we always want to please. We're people-pleasers, I think fundamentally, people are good, and they want to make another person happy. They don't really give you a fair evaluation. So the arts, definitely, and how you ask the question, asking the open-ended questions, and getting into the Five Whys. And there's a lot of theories around how do you phrase open-ended questions to get to the root cause of an issue that they may be happening, understanding what's currently going on, what are behavioral issues that are currently going on.

Mary Beth Privitera: So if I just pick an analogy, a simple analogy of redesigning a car, let's say. We know that the brake pedal is on one side and the gas pedal's on the right, brake is on the left. If we make a fundamental shift, well then, behaviorally, we're gonna have an issue. And we're gonna have adverse events. We're gonna have an accident. We look for that in the medical world and say, "What are these users really doing, and what do they love to do that are behavioral and just second nature?" Take those into consideration, and that's where it gets to the know-your-user, know-your-use environment because we take those into consideration and implement them into our product design of things either to include or avoid, then we're really taking into consideration on some of their own art, what they like to do.

Mary Beth Privitera: I think that one thing to pay attention to, that also may be a point of confusion, is the definition of use error versus user error. Use error is clearly defined in the FDA guidance. And there's a fundamental shift that I think has happened with that nomenclature and that is user error produces blame on the user, but use error means that it's designed in a way that the adverse event might have been predictable, that it was preventable. That it's not the user at fault but the manufacturer might be responsible for the designing and the labeling of the device in a way that promoted the error, that was inadequate in design. And I think that's where you get the scare factor, of, "Oh my goodness, this is a problem." It really gets down into, when you're generating a design, can you just sit back and think about and have empathy about what that user experience is gonna be and try to make it the best it can be and flip that on its head and say, "How do I make it better and improve it, rather than try to avoid the bad? 'Cause if I try to make it the best, I'll inherently avoid the bad."

Jon Speer: Yeah, that's a good tip. And I think the other thing I wanna explore with you a little bit on this topic is, I'm asked or have conversations often where I think there is this gross misinterpretation that if I am developing a medical device that I have to engage in a waterfall or a serial product development process, where I do step one, and complete all of step one before I do step two, and then all of step two before I do step three. I guess the debate that I sometimes am in the middle of, is FDA, regulatory bodies, they resist the notion of waterfall or Agile-type methodologies when it comes to product development. What do you have to say about that? Especially on this topic of user needs, do I have to do them all at the beginning? What if I'm a little bit later in my project, do I have an opportunity to go back and revisit that? Or what about waterfall versus Agile when it comes to human factors?

Mary Beth Privitera: Yeah, I think the funny thing is if I take a look at the graphic design, the waterfall diagram, and based on what I can historically reference, and keep in mind that I have academic tendencies to begin with, I found out that that was designed in the 1970s. And the interesting thing about that is it has the boxes and it has all the arrows and arrows go to review, and then it has, it kind of makes that circle as it comes back. And I think the focus of the people that look at that process, the waterfall process, that this box has to be done before I move on to the next box, aren't paying attention to the arrows. Because it says review and that might mean go back. And that might mean you go back to it and make this cyclical thing. If I change the emphasis not so much as to finishing the box, and I look at bringing it back in there, then I get into a much more iterative process.

Mary Beth Privitera: I think it's unrealistic to think that you're going to finish one box and then jump to another box. What I've encountered is that they are kind of getting into the end and then saying, "Oh crap, I need to do human factors and I haven't really considered it, I haven't really documented it." And they wanna do that final test just to meet agency needs, rather than looking at it as a fundamental customer need. 'Cause at the end of the day, your customers want a device that's easy to use, that's human factors. Why not put that in at the beginning instead of waiting to the end to meet a regulatory mark? I think it has to be an iterative process to get to that point, 'cause there's only one way to really get strong design, strong human factors, strong everything, strong quality to assure that I've taken into account my users and their use environment, and that is to just have iterative tests and iterative assessments. But it isn't a check box, it definitely is not a check box exercise.

Jon Speer: Yeah, for sure. Alright, so we talked a little bit about when to start and sort of how to capture that information. Now that that's a little bit clearer, from a human factors perspective, what happens next? Once I have captured those user needs, what are the next things that I should be thinking about and when should I be thinking about them with respect to human factors and the bigger picture of trying to get this product to the market eventually?

Mary Beth Privitera: Yeah, sure. I think you need to capture your user needs and have an idea and now you're ready to sit down and design, and design... The risk documents are very clear, design is your first go-to if you're gonna mitigate risk. We improve by design, and the user interface then is defined by the FDA as everything that would be provided to the user. It's the device, the labeling, the ISU, the packaging, all of that is considered the user interface. How often is it that we are just going to look at design standards that've been published and incorporating that into our product design? For example, the easiest way for me to approach this would be giving a hand tool example. Well, there's standards on hand tool design that's been around for eons, they're published, they're well validated. Even our alarm standards, there's new alarm standards that are coming out, that have validated sounds that are melodic, that have been tested. What does this sound mean when you hear it? What is this icon? We have standard icons that we know what they mean.

Mary Beth Privitera: Using those industry standards. AAMI HE75 is the only design standard that's out there, so start with what you already know. You can take a product design, let's say if it's a hand tool, I can go to the hand tool chapter and I literally can get a framework for what my hand tool might be, what are the controls and how those controls might be laid out. And I can even get down into more specifics to say, "Well, if I'm gonna put a push button on here, then this push button has to be within this reach, and have this maximum force, this minimum force." Now, I have some design specs that I can go with that I have some confidence in, that I don't actually really need to test because I've pulled it from the literature. And then using my user reviews to look at sort of the gestalt, the whole, the whole product design, the whole experience of, does it clinically meet access points? Am I in a comfortable body position? Am I not asking them too much?

Mary Beth Privitera: And this also gets true with software user interface designs, in that, I can look at design standards of grouping things together in aesthetic order and icons. There's a lot of standards that I think, once you get into the actual design of the device, that people just are either unaware of, or they don't know how to use them, that they should use them 'cause it will expedite their design. That would be the next step once I know where I'm going to implement into a product design.

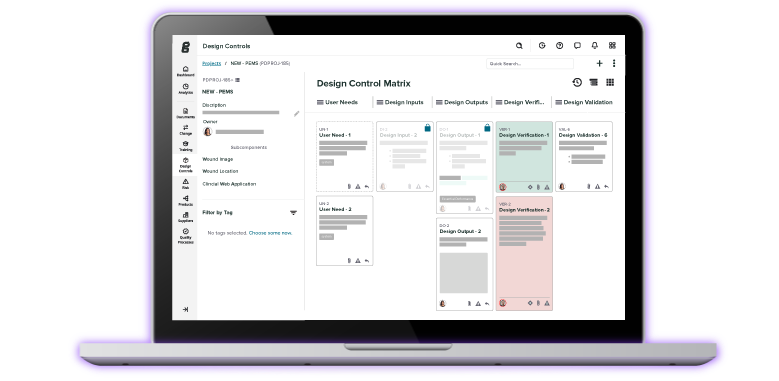

Jon Speer: Alright, that's terrific. And folks, I'm very much a design control nerd, and everything that, if you've ever read or heard me talk about design controls, everything that Mary Beth is saying should sound very familiar. And I think that's on purpose, right? Because as much as one is through the lens from a design control perspective, and the other concept is through the lens of human factors, these things are so intertwined. As I said at the beginning, maybe these are the same thing. Because it's really important that you understand what that user needs and then structure your design and development in a way that, it really is ostensibly, what you're trying to do is address two questions, "Did I design the product correctly?" and "Did I design the correct product?" That's really the essence of what verification and validation are all about, and human factors fits right into that whole paradigm.

Mary Beth Privitera: Yes, absolutely, absolutely. And like you, Jon, you might call yourself a "design control nerd", I have to admit it, I'm a design and human factors nerd as well. I think that's pretty obvious.

Jon Speer: [chuckle] Yeah, you and I, even today, we just decided... We knew roughly what we wanted to talk about, but it's like, "Hey, let's just hit record and let's just talk." You've been doing this for a few days, I won't give any indication of your age away, I'm not trying to do that. [laughter] But I guess, tell us... Share some stories where... Or maybe an ideal way that this should happen, based on your experiences. And if sharing a tidbit here or there of, "Wow, this was really done really well." Or, "Wow, this was done really poorly." Talk about some of the pros and cons of having a good solid human factors program.

Mary Beth Privitera: Sure. Well, I think one of the pros of a solid human factors program is that, that comment when you get to risk of that which is foreseeable, and "that which is foreseeable" is a great line. If you think about it and you think about raising a kid, you don't foresee all of the issues that our children are gonna come up with. We can kind of come up with a few and our users are the same way. We take a look at our medical device like it's our baby, and we're looking for that which is foreseeable on what potentially could go wrong and how the user might use it. We can't foresee all of them, so getting the user to do it for us is actually so much more helpful, because they have such rich information and, "Oh, no, I would never do it this way. Oh, I would definitely do it this way." That's the type of information that a solid human factors program can get you.

Mary Beth Privitera: I think there's some interestingly, shocking things that I've seen over the years, in terms of device use, where out in the real world, real world experiences, I think those are always fair to play, and those are far more shocking than I want to realize. For example, in doing contextual inquiry studies where you're immersing yourself in a clinical environment, you're always going to see things that you wish you didn't see, you wish that weren't that... That they condition. For example, maybe they're just breaking a little rule and maybe that little rule might be that they're off protocol or doing something that they may not be instructed to do. For example, we are studying Foley catheters and how they dispense the Foley catheters and the ICU nurse then put it... They didn't do it in the graduated cylinder, they just put it into the toilet to drain, which is not gonna cause anyone any harm, but it is not their protocol. And if you think about, and this is just a simple example, if you think about why they're doing what they're doing, well, they wanna get on to the next task, they don't wanna sit there and let that drain in an appropriate manner.

Mary Beth Privitera: And the reality is, is that getting in and watching cases is a gift and you always learn from those experiences and you walk away with a heartfelt emotion for both the patient and the provider because the provider wakes up every day and tries to do their best at their job, and sometimes, it's impossible for them to do the best they possibly can do because of the situations that we've created and as device designers. You can see things that happen also in the field where if there's multiple devices used in a system, each device is independently validated and independently approved. And when it gets to become a complex system, so if you go into the OR or the path lab and you look at these complex systems, you'll quickly realize that there's technical sales reps that are running around, that are providing technical support and the rules for those technical supports, "Why are they there?" Well, they're there to make sure that the device and the equipment are run properly.

Mary Beth Privitera: Well, that might not seem necessary, but if you think about it, if I can empower the users to do things on their own, I'm in a much better situation and I've got one less person that's involved in that particular care conundrum or that particular care situation where I don't have to rely on them actually being there. If it's an emergency situation, can they be there? Those are some of the issues that can happen when you're in the field. Then there's the usability... When you have a usability test, what can happen during a usability test that you just get surprises. That's why I say, "Try to start it immediately and do it often so you can get those surprises out of the way and you can design for them so that the device and the design in and of itself accommodate for those situations that might come up, that you had no opportunity of foreseeing."

Jon Speer: Yeah, that's really important. Mary Beth, I have to imagine that... I guess, pop quiz here. Does every device... [chuckle] I think last time I did MythBusters with you, so the thought just occurred to me.

Mary Beth Privitera: Pop quiz is good.

Jon Speer: Pop quiz. Does every medical device require human factors?

Mary Beth Privitera: Well, there's a lot of legacy devices out there that didn't have any human factors. And they are in a situation where they have to be re-validated and you have to search your mod databases and validate that they are, in fact, doing what they were supposed to do and intended and why the residual risk isn't a safe factor. The short answer is yes, I believe that it does. However, if you've had a device that's been on the market for a while, it's approved, and you're changing something in the internal mechanism, you're changing the board, the computer board that runs it, and there's no change to the device user interface, then technically you don't need to do a human factors update because you're already approved and you're not changing that basic user interface.

Mary Beth Privitera: I think increasingly, regulatory agencies are asking for it. What their focus again, is on risk and that is also another area of contention and area of confusion because in your risk analysis, you'll delineate whether or not it's an essential task or it's a critical task. Critical tasks get to those that relate to harm and that's the data that the agencies are really looking for. They wanna know on this critical task that someone can get injured on, did we take into consideration in have we reduced the risk to a reasonable level? I think that's... Short answer, yes. Long answer, maybe, maybe not. And that doesn't necessarily sit well in terms of how do you know what to do?

Jon Speer: Okay, so that's for things that might have already been on the market. What about if I'm in development, and let's just say at a stage where I'm preparing for a regulatory submission like a 510 [k], I guess, pop quiz question number two, do I have to address human factors as part of my regulatory submission?

Mary Beth Privitera: Yeah, you do. IEC 62366 is going to expect it to be in your file. It doesn't necessarily mean that you have to submit it to the agency directly. If it's got non-significant risk, so... Let just say that you have a device that was labeled, you went through and you even did a clinical trial and during that clinical trial, if the device used, you went through IRB protocols, and it was listed as a non-significant risk device, you still need to have something in your file that you've addressed it. I would recommend that you have a pre-sub meeting with FDA, if you're seeking FDA clearance, that assures that you are addressing all of their questions in your file in case you're audited. If it is something that has significant risk, then absolutely, it's without a doubt. If it is something significant with significant risk, and you have several critical tasks that are going to result in harm, then, absolutely, you need it, and that needs to be a separate filing, dossier filing, following the FDA Human Factors guidance and they're very clear on it.

Mary Beth Privitera: What's also interesting to note on that is there's a little bit of a difference between CDRH and CDER's definition of harm and a little bit of difference... They've got some comparative threshold analysis that happens on the human factors with CDER. That guidance just came out last September. There's a little bit of difference between devices and drugs and combination products that people need to pay attention to, but if it's a new product, then absolutely.

Jon Speer: Alright, so any other thoughts on the topic of human factors: When to start? What to do? How to document your file, before we wrap up this episode of The Global Medical Device podcast?

Mary Beth Privitera: I think don't be afraid of it, if you wanna do it anyway. It's a fundamental customer requirement and it'll only make your marketing and sales team quite happy when you have this very beautiful, lovely device that works as intended, and is a fantastic experience for the user. So don't be afraid.

Jon Speer: Well, and I'm gonna add to what Mary Beth just shared. Yes, your sales and marketing team will appreciate this at the end, and you might be met with resistance towards the beginning-middle when you start to suggest these things. So stay the course. It is the right thing to do. Remember that you're developing products to improve the quality of life and so understanding how humans interact with your product, because unless you're developing a purely AI thing, and even purely AI things have probably human intervention, realize that humans will be using your product in some way, shape or form. So this is an important topic.

Mary Beth Privitera: Absolutely, you're spot on. It's human design for humans.

Jon Speer: Exactly. Alright, I wanna thank Mary Beth Privitera. Again, Mary Beth is principal of research in human factors with HS Design. If you have any questions about anything human factors related... She writes books on this topic folks. She's a great resource to connect with, pretty easy to find her on LinkedIn. You could go to HS Design, hs-design.com to learn more about what they do as well. As we wrap up this episode of The Global Medical Device podcast, I just wanna let you know, did you know that Greenlight Guru is going on the road this year? That's right, folks, we have the True Quality Roadshow and we are gonna be hitting a number of cities across the United States throughout 2019. First stop is Atlanta, next stop is in Boston, and then we're gonna be hitting places like Minneapolis, and Orange County and a few other places throughout the States throughout the entire year. Be sure to check out the True Quality Roadshow. We'd love to meet you. There'd be an opportunity to sign up for these events when we're in a neighborhood near you, so do check that out.

Jon Speer: And of course, as you are going through human factors design and development risk, all of these things are important to define and document. And don't do it because you have to, do it because you believe in this, because you understand the importance of these activities in building and designing safer, more effective medical devices. I would encourage you to go to www.greenlight.guru, learn all about the Greenlight Guru eQMS software platform that is designed specifically for medical device professionals by actual medical device experts. And yes, they work here at Greenlight, it's terrific. So check that out. We've got workflows to help you better manage design controls, better manage risk and documents and all those postmarket activities like CAPAs and complaints as well, and it's all in one single source of truth. So check that out. As always, thank you for listening to the Global Medical Device podcast. This is the host, founder, and VP of Quality and Regulatory at Greenlight Guru, Jon Speer.

ABOUT THE GLOBAL MEDICAL DEVICE PODCAST:

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Nick Tippmann is an experienced marketing professional lauded by colleagues, peers, and medical device professionals alike for his strategic contributions to Greenlight Guru from the time of the company’s inception. Previous to Greenlight Guru, he co-founded and led a media and event production company that was later...