Examining the HHS Proposal for Premarket Notification Exemptions

What are the pros, cons, and ramifications of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) proposal that impacts the medical device industry?

In this episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast, Jon Speer talks to Mike Drues from Vascular Sciences about the HHS proposal, which focuses on down-classifying and exempting more than 80 types of devices such as exam gloves, thermometers, imaging systems, infusion pumps, and ventilators.

LISTEN NOW:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some highlights of this episode include:

- In January 2021, HHS declassified a number of medical devices without first consulting or notifying FDA. As a result, the reclassification initiative is on hold pending a review due to regulatory freeze.

- The HHS proposal affects seven (7) Class I devices (all gloves) and eighty-three (83) Class II devices, such personal protective equipment (PPE) and thermometers.

- It’s ironic that regulatory quality requirements apply to products but don’t seem to apply to processes that regulate those products. It’s another example of not practicing what you preach.

- Some companies want FDA to require feedback before down classifying and exempting changes. Reasons why? Safety, efficacy, and competitive advantage.

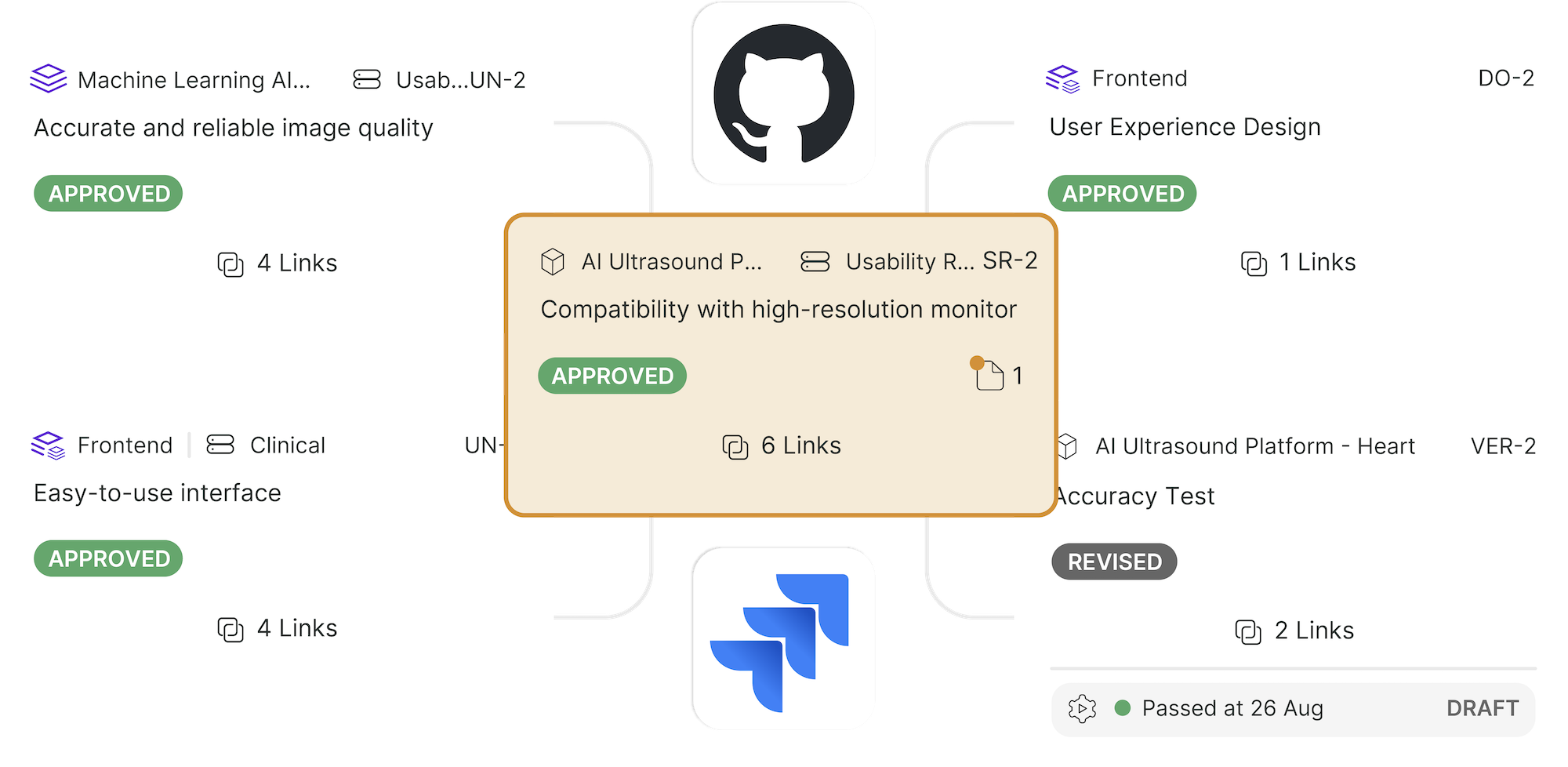

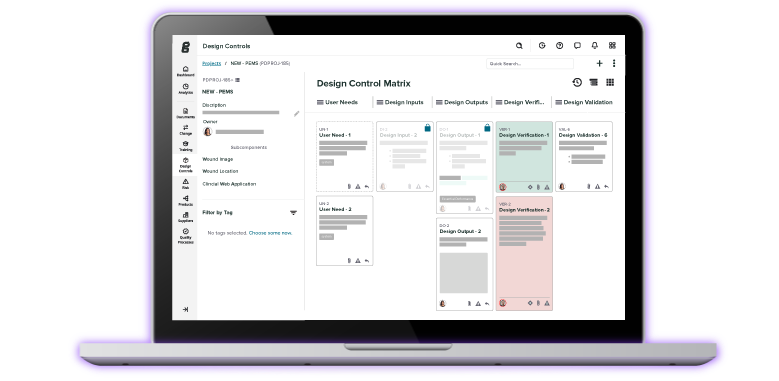

- Design controls, risk management, and quality management systems demonstrate that products are safe, effective, and meet indications for use.

- Proceduralizing and establishing processes is a way to describe how you operate and run your business. Why are they perceived as bad things and barriers?

- Recommended approach: begin with biology, engineering, then regulatory requirements.

Links:

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

HHS’ proposed 510(k) exemption proves the need for regulatory science

Device, digital health firms oppose HHS’ proposed 510(k) exemptions

FDA walks back Trump-era premarket notification exemptions

Emergency Use Authorization (EUA)

Overview of the 510(k) Process

De Novo Classification Request

Greenlight Guru YouTube Channel

MedTech True Quality Stories Podcast

Memorable quotes from this episode:

“Changing medical device classification, whether we’re going down or up, doesn’t matter, without notifying or consulting the folks that are responsible for evaluating these medical devices...politics aside, Jon, it’s hard to connect those dots. What sense does that make?” Mike Drues

“You don’t have to have a Ph.D. in biomedical engineering...to appreciate that gloves and thermometers and other forms of PPE—these are not the most complicated kind of products in the world.” Mike Drues

“It should not take a Ph.D. in biomedical engineering or an RAC after somebody’s name to appreciate that maybe it doesn’t make sense to lump gloves and thermometers into the same category as infusion pumps and ventilators.” Mike Drues

“Isn’t evaluating changes or the potential for changes, in this case in a medical device, always a good thing?” Mike Drues

“Things like design controls and risk management and establishing a quality management system is all about science. It’s all about demonstrating that the product is safe, that it’s effective, and that it meets the indications for use.” Jon Speer

Transcript:

Announcer: Welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast. Where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Jon: Hi, this is Jon Speer with Greenlight Guru and as always, thank you so much for listening to The Global Medical Device Podcast. A couple of weeks ago, Mike Drews and I sat down and talked about a policy that was suggested by HHS before the changeover in administrations that impacted the medical device industry. Now, we're going to go ahead and share that podcast with you all, but there has been some updates on this particular topic since we recorded that. It sounds like FDA has stepped in, in a good way, and intervened some way. So, I think there's still a little bit more that's going to happen on this topic. However, I think that the initial proposal is going to be quite a bit less than what was originally proposed. I think, in my opinion anyway, this is probably a good move from the FDA. Enjoy this episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast. On this episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast, familiar voice, and hopefully now familiar face, Mike Drews from Vascular Sciences, joins me. We talk a little bit about this proposal that came out from HHS for the middle part of January regarding down classifying and exempting. Something like 80 some devices or device types, including things like exam gloves, but also things like infusion pumps and ventilators. We talk about the pros and cons and some of the details and the nuances behind such a proposal. So enjoy this episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast. Hello, and welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast. This is your host, and founder, and Greenlight Guru Jon Speer, and joining me familiar voice, and I guess face now, to the Global Medical Device Podcast. This is Mike Drews with Vascular Sciences. Mike, welcome!

Mike: Thank you, Jon.

Jon: Well, as we're recording this, we're into the second quarter calendar year 2021. Obviously, a few months ago, there was a new administration that took office here in the United States, and as is typical for that sort of event, it's circumstance. Sometimes there's a change in policy or interpretations of policies on a number of fronts, but as you and I are going to chat a little bit about today, are we starting to see some changes or potential changes on the horizon with respect to policies and regulations that impact the medical device industry? I know there was a proposal that, gosh, I guess it was a little bit ago. I think it was actually before the transition, an HHS proposal, changing some classification and some exemptions for devices. I guess Mike, maybe a good place to start is let's talk a little bit about this proposal from Health and Human Services or HHS.

Mike: Yeah, I think it's a great topic for discussion, Jon, and as always, thanks for the opportunity to have this important and certainly timely discussion with you and your audience. Always nice to speak with you and still getting used to seeing one another.

Jon: I know.

Mike: So, thanks for that. First of all, this idea of re- classifying existing medical devices, as you know, Jon, it's certainly not a new idea. This is something that FDA has been doing for many, many years. Even decades. Occasionally, FDA will down classify devices, or even less commonly, will up classify devices as more and more information is gained about those products. That's absolutely not a new idea. As a matter of fact, FDA is now required under the 21st century Cures Act to reevaluate the classification of medical devices every five years. I think overall, that's a good thing, to be able to make adjustments in our level of regulation in a wide variety of products as additional information is gained. In this particular case, however, I think it's the way that it was done that's most interesting to me. Specifically, as you mentioned in January. January 15th to be precise, apparently department of Health and Human Services, literally in the days before the previous administration left office, made this announcement about declassifying many medical devices, without consulting the FDA first.

Jon: Wow.

Mike: Now think about that Jon. Changing medical device classification, whether we're going down or up doesn't matter, without notifying or consulting the folks that are responsible for evaluating these medical devices. I mean, politics aside Jon, it's hard to connect those dots. What sense does that make? As a result, this whole initiative, this whole re- classification is currently on hold pending a review. Which is, I think, a good thing. It's part of the more broad regulatory freeze that the current administration has put on all of the latest changes that the previous administration tried to put into effect before leaving offices. I think it's also important not to over- generalize their job. There's just one more thing I'd like to add, and then I'd love for your two bits on this as well. What kind of devices are we talking about here? Well, in general, we've got seven class one devices, all gloves by the way, and 83 class two devices, which can include things like PPE's, personal protective equipment, thermometers. I don't know about you, Jon, but you don't have to have a PhD in biomedical engineering, which by the way I do have, to appreciate that gloves, and thermometers, and other forms of PPE, these are not the most complicated kind of products in the world.

Jon: That's right.

Mike: But in this same category of down classifying, we also have devices or components of devices like imaging systems, like infusion pumps, like ventilators. Once again, Jon, and I don't mean to be overly facetious here, but it should not take a PhD in biomedical engineering, or an RAC after somebody's name, to appreciate that maybe it doesn't make sense to lump gloves and thermometers into the same category as infusion pumps and ventilators.

Jon: Yeah.

Mike: I think there's a lot of interesting tangents that we can go off on this topic, Jon. I laid down a few, feel free to pursue whichever you think are of interest to you and our audience.

Jon: Well, I think that was the interesting thing to me, to echo your sentiment. When I read this proposal, some of those like," Yeah, okay. That's certainly makes sense. Gloves, thermometers, PPE. Okay. I can see those products being exempt", but when you throw in things like ventilators and infusion pumps? Oh my goodness! These are life supporting, life sustaining type products. And it's like," That seems weird to me." I guess as I was reading it, I was wondering, does this have some sort of connection to all the EUA products that have been cleared? And many of these products were popular, so to speak from an EUA perspective, and I was curious. Is there some sort of motivating factor, or influence, a connection if you will, for these products that are proposed by HHS being exempt and those that have EUA, do you think there's any sort of connection or am I grasping at something that may or may not be connected?

Mike: On the contrary, Jon. I think there's definitely a connection. Many of these products are COVID related products. In other words, they're products that are very important in this COVID pandemic that we're living through. Hopefully, we're approaching the end of, but we're certainly still living through it. It's very true, as you and I have talked about before Jon, and I said it to one of my customers earlier this morning. We have a device on the market now under an EUA, and now we're following up with a 510( k) case so that the company can keep the product on the market. Once the EUA time's out, when the pandemic is deemed over by the secretary of Health and Human Services, simply put, the level of evidence, the regulatory burden if you will, to obtain an EUA, an Emergency Use Authorization is much, much lower than it is for a conventional clearance or approval. That is a 510( k), or de novo, or a PMA. As it should be, because these products were put onto the market to meet the specific immediate needs of the emergency. All of this Jon, is under current review or re- evaluation under this regulatory for use, which is obviously to most people, it sounds like a political move, and of course it is.

Jon: But the regulatory freeze happens with every administration change.

Mike: Well, that's one of the points I was going to make, Jon. That's exactly right, and that it does set up an interesting precedent, because every time a new administration comes in, could they, should they implement a regulatory freeze to reevaluate the changes of the previous administration? As a matter of fact, Jon, I take that maybe even a step further. I think it's a good idea to do that, but not for political reasons. Even if there's not a change in administration, I think we should be constantly re- evaluating the changes or the proposed changes that we make. Here's perhaps an irony, that you more than anybody, will appreciate as one of the biggest gurus of the quality side of the world that I know, and that is: isn't evaluating changes or the potential for changes, in this case, in a medical device, always a good thing? In other words, isn't it ironic that one of the quality requirements in the QMS is to have change management system where before you actually implement a change, you have to evaluate that change to make sure it doesn't impact the efficacy performance, yada, yada, yada. I find it interesting, Jon, this is just yet another example, and we've talked about other examples before, where we don't seem to practice what we preach.

Jon: For sure.

Mike: That is, we have regulatory, or this case quality requirements, that apply to our products, to our devices, but what they don't seem to apply to the processes that we use to regulate them. And I don't know about you, Jon, but I think that's a pretty big irony to me.

Jon: It's a huge irony. And usually in normal everyday circumstances, I'm a huge fan of irony and sarcasm, at least in form of humor, but in this case, it is curiously ironic. It's not surprisingly ironic. In addition to what you mentioned that generally, whenever we as med device company make a change, we have to assess the impact, evaluate that change before implementing that change. The other thing we need to do is monitor the change after it goes into effect to basically verify its effectiveness. This is one of those scenarios where nothing like that is happening from a regulatory body perspective, regardless of if it's FDA or outside the United States. This is just not how regulatory bodies operate.

Mike: As a matter of fact, Jon, I'll give you another quick example of how we don't practice what we preach, and that is, in my recent presentation that Greenlight invited me to do as part of the MDRs. One of the things that I pointed out is we have a lot of changes or proposed changes going into effect in the EU. The question is, what evidence do we have that these changes will do any good? In other words, one of the things that I pointed out in my presentation is: at the end of the day, if all of these changes that we're talking about, or in some cases even have already implemented in the EU, or even changes here in the United States, if they don't ultimately translate into safer and more effective products, two years from now, five years, 10 years from now without being overly cynical, Jon, isn't this a colossal waste of time and money? In fact, isn't it a tremendous source of job security for the regulatory folks and the notified bodies. That's being really cynical, Jon. But of course, there cannot be any truth to that, could there?

Jon: Yeah. Right? Yeah.

Mike: We're going for the fringes here, Jon.

Jon: Yeah, we are, for sure.

Mike: I should've warned you.

Jon: But no, it is interesting though, there's this perception, I don't know where it comes from. I know what I'm about to say is borderline polarizing depending on perception, but is this all fake news? Is this in that category too, where like what is wrong with the medical device industry? Is there anything wrong? Is this perception that we need more and more and more regulations to govern. But then here's, to use the ironic twist, we have this proposal from HHS that did not consult FDA, doesn't seem like they consulted the industry, making some broad sweeping proposals on making certain devices exempt. Some that, frankly, shouldn't be exempt from any sort of submission. This just doesn't make any sense.

Mike: Well, let's try to make some sense out of this, Jon, because on one hand I'm sure that it's a certain amount of skepticism or perhaps even cynicism is appropriate, but more importantly, I want this to be a realistic discussion. I want this to be an open and honest dialogue. Some of the companies that I work with that are current customers of mine, they have products in the areas that HHS is proposing to down- regulate. In a couple of cases, the companies have submitted feedback to the agency, because they want feedback on this, discouraging them from implementing these changes. But the question is why? The answer that the company provided to the FDA has everything to do with safety and efficacy and so on. But I'll be honest with you, Jon, one of the things I appreciate about our forum is we get to talk about, or let me not put you on the spot here, I get to talk about things in a certain specific detail, but at the same time, not mentioning company names or specific products. So, let's talk about what the real reason why these couple of companies, two in particular are customers of mine, want FDA not to do this. Not because of safety and efficacy, that's a side benefit, but the primary reason is because of the competitive advantage.

Jon: For sure.

Mike: A view, having to do a 510( k), whether it's justified or not, has a competitive advantage. In other words, if another company can bring a similar product onto the market without having to jump through the hoops of 510( k), then that would be a significant advantage to the competitor and perhaps, a disadvantage. Not suggesting there's anything inherently wrong with that, but of course, as you can appreciate Jon, when we go to the FDA to say, we don't think that we should implement that change, nobody's going to be that honest and say exactly why. In this era where everybody, including my politician friends at FDA say," We want more communication. We want companies to come and talk to us." I hear a lot of talking, going on, Jon. What I don't hear a lot of is actual communicating. Just because two people are talking doesn't necessarily mean they're communicating.

Jon: For sure. I can see that side of the discussion, and I can understand it. If I had a product that is being proposed as down classified and when I brought this product to market, whether it was last year or 10 years ago, whatever the case might be, the burden of proof, the responsibility, the obligations that I had to demonstrate, not that they're insurmountable, but they're more significant than not having to demonstrate any of those things. I understand that from a competitive point of view that from some of these companies' perspective. I get that.

Mike: And one other point I would like to mention Jon, and I think it's a very important point. Maybe even arguably the most important point in our discussion and this topic in general. Look, in my opinion, there's way too much emphasis here on talking about the regulatory process. In other words, whether or not you actually have to submit a 510( k). Let's be honest, Jon, as you and I have talked about before, that's largely a matter of paperwork.

Jon: For sure.

Mike: What is much more important to me is, from a biology and engineering perspective, did the company do what they should have done in terms of the development and the testing and so on? Whether you take that information and package it up in the form of a 510(k) and submit it to the FDA, or it's a class one exempt, or even if it's a wellness device, which is not evaluated by the FDA at all. It's the information itself that I think is infinitely more important than the package, than the paperwork that we use to convey that information. I would like to think, I'll take this a step further, Jon, and we've talked about this before as well. I would like to think that we work in an industry where people would do the things they know that they should do, or at least they should know that they do, whether they're developing a glove, or a thermometer, or a ventilator, or an infusion pump, or an artificial heart. But unfortunately, Jon, I guess I just didn't fall off turnip truck yesterday because regrettably, there are some, hopefully not the majority, but there are some out there that will only do what they are absolutely required to do. What they have to do, and not one bit more, and I think, Jon, that's a problem.

Jon: That is a problem. I mean, sometimes I have conversations with folks and they're like," Oh, I'm class one. I don't have to do design controls. I don't really need a full quality system." And that just drives me crazy because, okay, technically speaking, if you have a literal interpretation of the regulations, that those may be true statements. My response is, well things like design controls, and risk management, and establishing quality management system, it's all about science. It's all about demonstrating that the product is safe, that it's effective, and that it meets the indications for use. The whole idea of proceduralizing and establishing processes is just a way to describe how you operate and run your business. Why are these bad things? Why are these perceived as negative barriers in these cases? I suspect there are some folks who might be reading this proposal and thinking," Oh, finally, we can do something carte blanche, without a lot of regulatory burden and all these sorts of things." And I agree with you. I think that's a terrible, terrible mindset. Unfortunately. We are making medical devices and these are products that are to help improve the quality of life, and some cases may save a life. I want to go above and beyond to make sure that that product performs when it needs to, how it's supposed to.

Mike: Could not agree more, Jon. It's funny, you mentioned the word science here, and some of the people, some of the articles that led to our discussion today proposed that the solution to this problem should be to apply regulatory science. Maybe we should move on to the last part of our discussion and talk a little bit about what exactly is regulatory science. You've probably heard this phrase before, Jon. Do you have any idea, thoughts on what is regulatory science? If there is such a thing?

Jon: It is a little bit of a head- scratcher to me. Take the adjective off. Science, I understand that for sure, but what is the regulatory science? That one was a little bit of a conundrum for me to be quite honest. What is your take on this term and why is it meaningful, or is it meaningful?

Mike: Let me start out by saying, as an adjunct professor at a number of universities, including some Ivy league schools, I started out by consulting what is the absolute authority here, and that is Wikipedia. Here is what Wikipedia, and I hope everybody appreciates my not so subtle use of humor. I got worried for a second there, because you weren't laughing immediately.

Jon: I had water. I didn't want to spit it out on the camera.

Mike: Here's what Wikipedia says regulatory science is. Regulatory science is the science of developing new tools, standards, and approaches to evaluate the efficacy, safety, quality, and performance of medical products in order to assess benefit risk and facilitate a sound and transparent regulatory decision- making process. That's what Wikipedia says is regulatory science.

Jon: Okay.

Mike: Now I'm saying I agree with that or not. I just have a couple of observations. First of all, isn't what I just said, isn't that the overall purpose of the entire regulatory process? In other words, isn't that why we go through a pre- approval process for a class one exempt registration, or a 510(k), or de novo, or PMA. And further, isn't that exactly why we were supposed to, as part of our post- approval process once our product is on the market, keep an eye on our device, or for that matter, our drug while it's on the market? What is unique about this idea of regulatory science that we haven't been doing, or at least supposed to be doing for decades? That's point number one. The next point in this question of what is regulatory science, is there a such a thing as regulatory science? I've taught over the years in more than a dozen different regulatory science programs at the graduate level and unfortunately, the way a lot of people, certainly not everybody and certainly not me, but the way a lot of people approach regulation as you and I have talked about before Jon, and I think they approach quality like this as well, following the regulation like a recipe. Executing lines of code like a computer one after another, after another, without ever stopping and asking, does this recipe, does this code, does this process make sense? Now, to me, Jon, I don't know how we can argue that something is a science or a scientific process if we're just simply following steps like a recipe without thinking. I don't know, is it just me Jon, or how do we connect those dots?

Jon: To me, when I hear science, I don't remember what grade it was in, but one of the first ideas that pops into my brain is the scientific method. I'm not going to regurgitate this verbatim or exactly. I'm probably going to leave some of the stages of the scientific method out, but yeah, you formulate a hypothesis and you conduct experiments to prove or disprove your hypothesis and then you iterate and you learn. To me, that's what science is. Right? So your point, this doesn't sound like science in many cases, this sounds like," Okay, which process is applicable." Okay. And then I'm going to, to your point, follow blindly and going through this checklist sort of mentality. Back to something I think you said earlier, the method by which I get to market from a regulatory perspective, for all intents and purposes, is sort of irrelevant. It's the vehicle by which the regulatory agency needs the information presented to them, but the science that I go through to get my product there, that methodology is irrespective of classification or that regulatory vehicle. In my opinion.

Mike: I could not agree more with you, Jon. I think, once again, you and I are singing the exact same song, just maybe in a slightly different key, but we're definitely singing the same song here. To me, rather than using the word science, I like to think about it like a process and more specifically like a thinking process. Bottom line, do we need regulatory science? In my opinion, absolutely. Yes, no question about it. But do we practice regulatory science? Once again, in my opinion, absolutely not. By the way, I take no pride in saying this about our industry. Not just people working in companies, but when I hear people in regulatory agencies, whether it's the FDA or some other part of the world. Because as you know, Jon, I do business with companies all over the world, and somebody tells me to do something for no other reason than this is what the rule says on the piece of paper with no justification, certainly no justification based on engineering or biology. To me, Jon, that's not science, that's nuts. You asked me at the beginning, what is regulatory science? I gave you the Wikipedia definition. Now, let me give you for what it's worth, Mike Drews' definition of regulatory science, which is nothing new to you and to our audience that have heard us talk about before. It's one of the many important things that differentiate my approach to regulatory compared to many others. And that is, I always begin with the biology and the engineering first.

Jon: For sure.

Mike: Then we consider the regulation after that. Which, when you think about it Jon, is the opposite, is the antithesis of the way that most people play this game.

Jon: For sure.

Mike: Most people they go right to the regulation. What does the regulation require? Step one, step two, step three, and so on. In my opinion, that is totally, pardon my French, back asswards. We want to begin with the biology and engineering first. I say to my customers all the time, if you can convince me, nevermind as a regulatory consultant, but as a professional biomedical engineer, on the merits of your biology and the engineering. In other words, if the biology and the engineering makes sense, don't worry about the regulatory. We'll figure out how to make the regulatory work, but the biology and the engineering, they have to work first. That's where this should begin. That's my definition of regulatory science. And one step further there's an adage, I'm sure you've heard currently in medicine," The surgery went perfectly, but the patient died anyway." Well the engineering equivalent," We designed our medical device perfectly, but the patient died anyway." The regulatory equivalent," We followed the regulation perfectly. That is, we did all that FDA or Health Canada, whoever it is asked us to do, and yet the patient died anyway." The reason why this happens more frequently than some people would like to think, in my opinion, is because we are not using regulatory science. We are not beginning with the biology and the engineering first.

Jon: Right.

Mike: When we get with the regulation first, in my opinion Jon, maybe some people might disagree, but in my opinion, that's a big mistake.

Jon: This is a thought that's been on my mind for some time. I don't think I'm going to throw you off too much with this, but there's been, for as long as you and I have known each other, probably even longer than that, there's the whole 510( k) vehicle has often been called into question. There's been attempts here and there to sort of repackage or iterate on, and I'll use their quotes, iterate on the 510( k) vehicle. So many people do get hung up on," Oh, it's going to be a class three and require a PMA, blah, blah, blah." And you and I have talked at length in the past about there might be some strategic benefits for PMAs and de novo's and things like that. But so many people in this industry are so stuck on that. Would the industry benefit from removing all of those things. Who cares what they're called and what the vehicle is. Demonstrate the burden of proof is on you from a biology and an engineering perspective, make your case. Who cares what you call it at the end of the day, just demonstrate that. Maybe get the focus back where it needs to be.

Mike: You know, Jon, that's a very interesting idea. I think there's a lot of merit to that idea. The way you phrase it," Who cares what you call it?" Shakespeare said exactly the same thing, but in a slightly more elegant way. He said," A rose by any other name still smells as sweet." This goes back to what I said earlier, whether you call it class one exempt, whether you call it a 510( k), whether you call it a de novo or a PMA, or you call it a CE mark or anything else. At the end of the day, it's the work that goes into it, the content that's most important. But on the more pragmatic side, Jon, here's an interesting statistic for you that I just came across recently, and I haven't had a chance to fact check it completely myself, but it was published in an article. Let me ask you this question, Jon, comparatively speaking, how long do you think it takes FDA to evaluate a 510( k) as opposed to a PMA?

Jon: I'm going to guess a PMA is probably at least two, probably three times longer for FDA to review.

Mike: Good guess. It's actually quite a bit more than that. According to these statistics, and again, I need to fact check them, but they were published in one fairly reputable source, not Wikipedia. But according to this particular source, FDA takes 20 hours to evaluate a 510( k), whereas 1200 hours to evaluate a PMA. 20 hours for a 510( k) as opposed to 1200 hours for a PMA. If you do the arithmetic, Jon, and I did this just to confirm, 60 times longer. Six, zero times longer to evaluate a PMA than a 510( k). Now to be fair, Jon, whether it's 30 times longer or 60 times longer or whatever it is, do you think that's a bad thing? Because, let's remember, that PMAs we're talking obviously class three devices, often, certainly not always, life supporting or life sustaining devices. In other words, often, not always, if the device works, the patient lives, if the device doesn't work, they die. In the class two universe for 510( k) and de novos, some devices fit into that category of life or death, but most do not. I guess when people in industry complain about a burden that a PMA imposes over, say a 510( k), or even a de novo, the question is, is that a bad thing, or perhaps should it be that way? And take it one step further, Jon, on the drug side of the world, if drug companies made that same argument that an NDA is too much work, we would never in a million years have a new drug on the market. I think that, to a certain extent Jon, it's become sort of a convenient excuse for our industry to blame the increased regulatory burden of the PMA over a 510(k) when overall, I think that's the way that it should be. What do you think, Jon?

Jon: It seems like 20 hours is light from a 510( k) perspective.

Mike: That's what it seems to me, but that's the statistics that were reported here.

Jon: But nonetheless, to your point, I think that's the important thing about this, is I hope regulatory agencies are spending more time on riskier products, and devices, and technologies. I hope so. Right? Because that's the idea is the biology, the engineering, the science that went into those should be more complicated than something that's a little less or more or less benign, or passive from a product perspective.

Mike: Well, not to belabor the conversation, Jon, because I know we do need to wrap this up, but one of the ideas that I floated in one of our podcasts, I think probably a couple of years ago now. In the PMA world, when we were talking about the PMA, in the class two and below universe, we separate ME 2's, the 510( k) s from the duly new and novel, we call those de novos. In the PMA world, we make no similar differentiation between the two. In other words, let's be honest, Jon, even in the PMA world, there are a heck of a lot of ME 2's. Heck of a lot of ME 2's and very, very few new and novel PMAs. So, does it make sense if this statistic that I shared a moment ago is accurate that it takes 1200 hours for FDA to evaluate PMA 60 times longer than a 510( k)? Does it make sense to apply 1200 hours of resources to a ME 2 PMA, as opposed to newer novel PMA? In other words, we have some other type of PMA for ME 2, call it a 510( k) PMA if you want. Anyway, you understand the point that I'm trying to make.

Jon: Yeah. Yeah. In a sense, almost create a different vehicle within the PMA bucket, I guess.

Mike: This is my interpretation of regulatory science. I want to apply the most resources to the products that need it.

Jon: Exactly!

Mike: Not the products that don't. And if we don't do that, isn't it an oxymoron to even have a conversation about regulatory science? Something to think about.

Jon: Well, Mike, thrilling conversation. We don't often dive into the politics of things and I guess we didn't really here either. Nonetheless, we did talk a little bit about some of the ramifications when politicians get involved with establishing new proposals and policies in this industry without consulting the regulatory experts and regulatory bodies and agencies. Certainly fascinating. I guess, to wrap things up today, do you think this HHS proposal has a snowball's chance in moving forward?

Mike: Well, I think it does have, because I think it is. As we talked about, we have this regulatory hold while we're re- evaluating. In terms of the specific devices that are being proposed to be down classified, I really think that it's inappropriate, or even flat out dangerous, to talk about them in a ubiquitous sense. I think we have to go case by case by case. I think as we talked about before, Jon, it doesn't make sense to consider gloves and thermometers in the same category as ventilators and infusion pumps.

Jon: For sure.

Mike: My response, I would like to think, and the FDA will, if they do this, is they will go through this list and parse this list one after another and ask, does this one make sense to be down classified? Yes or no? Does the next one make sense to be down classified? Yes or no? Once again, Jon, not to beat a dead horse here, but if there is such a thing as regulatory science, then that's the way that it should be practiced. Not lumping everything together.

Jon: All right. Well, Mike, I appreciate your insights on this and folks, stay tuned. Certainly if there's any updates on this, or any other regulatory matters, we'll discuss it and the ramifications of such decisions on the Global Medical Device Podcast, and there's a very good chance that Mike Drews from Vascular Science would be the person that I'm chatting with about it. Because as you've heard me say before, no one understands this and applies, I would say logic. I think that's a fair way, a logical approach to this because I think a lot of the methodologies and a lot of what you're going to hear from other regulatory consultants, quite frankly, is the opposite of logical. It's very methodical, but not in a way that that uses their noggin. So, if you want somebody that used the brain to think about this in a way that's refreshing and unique, but to your advantage as a medical device company, then I want to encourage you to reach out to Mike Drews with Vascular Sciences.

Mike: Thank you, Jon. How about this last tidbit? The opposite of logic is regulation. Good regulation should always be based on logic, and if the regulation is not logical, then I'm sorry, it's not good regulation.

Jon: Amen for sure. Folks, thank you so much for listening to the Global Medical Device Podcast, and hopefully you've been enjoying the video aspect of that. If you are watching on YouTube or other sources of video, be sure you subscribe and click the notification so that you can get informed of when the new episodes are alive and ready to consume. Thanks so much! And as always, this is your host, and founder, and Greenlight Guru Jon Speer, and you have been listening to The Global Medical Device Podcast.

ABOUT THE GLOBAL MEDICAL DEVICE PODCAST:

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Nick Tippmann is an experienced marketing professional lauded by colleagues, peers, and medical device professionals alike for his strategic contributions to Greenlight Guru from the time of the company’s inception. Previous to Greenlight Guru, he co-founded and led a media and event production company that was later...