Enabling MedTech Innovation through Cross-functionality

The medical device industry strives to develop high quality and innovative products that will contribute to the improvement of patients’ lives

Today’s guest is Bruce Gingles, one of Jon Speer’s first bosses and mentors as a medical device professional. He taught Jon about medical device product development and patients. Currently, Bruce is vice president of Global Technology Assessment and Healthcare Policy at Cook Medical. He’s also the co-author of Medical Innovation: Concept to Commercialization.

LISTEN NOW:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some highlights of this episode include:

- Barriers to Business: Bruce’s role is identifying and breaking down barriers to connect with customers and put products on the market that make a difference.

- Bruce presents a cross-functionality of understanding the market, clinical, and patient needs to effectively communicate with sales, marketing, and other areas.

- Bruce expresses appreciation for the impact I had on Cook’s quality engineering and design control process.

- Shift in Healthcare Technology: Who better to solve clinical and healthcare problems than doctors and nurses? Now, it’s a conflict of time and commitment.

- Passion vs. Profit: Separating the inventor/doctor from the evaluation of the early product impedes manufacturer’s ability to be true to that person’s vision.

- People making buying decisions for hospitals are removed from the practice of medicine. Decisions were based on clinical outcomes, but now also control costs.

- Current trend is a reduction in new ideas that relate to therapy, and more ideas for diagnosis. They’re not keeping pace with the number of solutions to problems.

- Solution: Insist that inventor is the operator during prototype evaluations and assign objective chaperone to validate patients and accuracy of records of cases.

Links:

Medical Innovation: Concept to Commercialization

MedTech True Quality Stories Podcast

Memorable Quotes from this episode:

“Try to identify what these barriers are...so that it’s easier for us to connect with our customers and put the products on the market that make a difference.” Bruce Gingles

“We worked very closely with physicians. The doctors that we worked with...they were inventors of products and technologies.” Jon Speer

“If they take time out to develop an important new technology, the hospital may see that as a conflict of commitment or conflict of time.” Bruce Gingles

“For many physicians, if they can’t ultimately practice their art on their patients, there’s very little incentive to spend the time developing it.” Bruce Gingles

Transcription:

Announcer: Welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast, where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Jon Speer: All right, this episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast was really a treat for me, and here's why. I got to talk to one of my first bosses as a medical device professional, a great mentor of mine, someone who taught me a great deal about medical device product development, about patients and how important they are in the equation of a medical device professional. Learned so much from this guy. So enjoy this episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast.

Jon Speer: Hello, and welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast. This is your host, the founder and VP of Quality and Regulatory at Greenlight Guru, Jon Speer. Folks, a lot of you listening, you're in this, obviously, this medical device industry, you're trying to be innovative, creative, you're trying to develop awesome products to improve quality of life. So as luck would have it, or serendipity, however you wanna look at it, I suppose, I was in the airport the other day. I think I was in... Gosh, I don't remember where I was, to be quite honest, but nonetheless, I bumped into an old friend, an old mentor, a former boss, I guess, if you will, Bruce Gingles. Bruce is the VP of Global Technology Assessment and Healthcare Policy for Cook Medical. So Bruce, welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast.

Bruce Gingles: Thank you, Jon. It's nice to be with you.

Jon Speer: And when we bumped into each other in the airport, you shared a little bit about what you're doing and, of course, I wanna give you a chance to share with the folks a little bit about that today. But you opened your bag and showed me this book that you have written, or co-authored, called Medical Innovation: Concept to Commercialization. And the few minutes that we talked reminded me back of those early days, and I wanna talk a little bit about that today as well as where things are going. But I guess tell us a little bit about your role and some of the things that you dive into, not only for Cook, but also for, frankly, the betterment of the entire medical device industry.

Bruce Gingles: Well, let's see. I began my career at Cook as a sales representative in California, and then as our business... And I was the first employee of our young critical care division, and as that division began to grow and we had more products and more people coming on, there was a need to have some support in the office. So I moved from my territory in California to our office in Bloomington, Indiana. And once I moved, I added the responsibilities of marketing, and today, I think what we sort of call business development, looking for the types of products that our customers would have interest in. I was eventually put in charge of that whole unit for the global sales and marketing and product development.

Bruce Gingles: And then in the last roughly 10 years, I began to sense some changes in our marketplace, both clinically and politically. And many of the changes I was observing were really barriers to our business, sort of threats to the way we had always conducted our affairs. And so I transitioned over into a role that helps me, and on behalf of Cook, try to identify what these barriers are and ways that we can break them down so that it's easier for us to connect with our customers and put the products on the market that make a difference.

Jon Speer: That's terrific. So, Bruce, I might share some things with you today that you might not even realize, but folks, I started in the medical device industry in the late '90s as a product development engineer, and my first boss, I mean this as a compliment, sometimes that term "boss" gets thrown around as maybe not so much of a compliment, but boss and mentor was Bruce Gingles. Bruce was the head of the critical care business unit. I had the extreme pleasure of being a product development engineer. And I learned so much from you, Bruce and some things that I think you get that I think, unfortunately, in my experience 20 years later, they're not very common in the medical device industry. And one thing that I think you understand is, there has to be a complete cross-functionality, understanding the market need, the clinical need, the patient need, understand how to communicate that through sales, development, marketing, manufacturing. That has to be a very holistic point of view. So I wanna credit you for a lot of things that I learned, I, certainly in my formative years of my career, I learned from you. So thank you for that.

Bruce Gingles: Well, and thank you for that note. And I will say, Jon, I don't know if we ever talked about this, but when we were working together, you were around in the very early days of new expectations on engineering for quality processes. And this was around the time we started hearing terms like CQI, Continuous Quality Improvement. There was a whole vocabulary that was developed around this. And you were one of the people that really before anyone that I remember in the company, realized that language like FMEA, Failure Modes and Effects Analysis, these design controls which were brand new to our company and to the industry, you really were a pioneer, certainly for Cook, in helping us get in front of the whole quality engineering and design control process. In fact, you were heading up that portion of Cook's business, which now has grown into a whole huge division. But at the time, it was quite small and I don't think any of the rest of us quite appreciated the impact that that was gonna have on how we designed, developed and manufactured the products. So, it was really fun to watch you pick up on that little seed and grow that into what now has become a major part of not only Cook's business but every company in the device industry. So thank you for that.

Jon Speer: Oh, I appreciate you saying so, and it's certainly my pleasure. I've learned a ton and I'm very fortunate for the opportunities that I've had, so I appreciate you saying so. But when I saw you in the airport, I kinda went back to... I think being a product development engineer is fascinating, it is a lot of fun. I think it's a little bit different today, and you and I are gonna chat a little bit about why that might be, not only from the product development engineer perspective but maybe from the inventor, specifically the physician inventor perspective. But one of the things that we did a lot back in those days in critical care is, we worked very closely with physicians, not only do we work closely with physicians but the doctors that we worked with, the anesthesiologist, the ER docs, the surgeons and so on, they were inventors of products and technologies.

Jon Speer: And I tell people all the time that you'd be at the American Society of Anesthesiologists or College of Surgeons or whatever, and you'd have a meeting with the doctor and sometimes they would literally bring you a cocktail napkin sketch for something that they had gotten their pen or their Sharpie out and drawn something, or in other cases they might have grabbed some different parts and pieces from their lab and glued things together, and a crude prototype but that was fascinating, to be able to work with that physician inventor to understand what problem they're trying to solve and then be able to go and do that and design and test and basically get that product ready for manufacturing. It feels like things have changed a little bit though. Certainly in recent years, it seems like that doesn't happen as much these days. Would you agree with that?

Bruce Gingles: Yes, I would completely agree with that. No doubt about it.

Jon Speer: And I think it's unfortunate because who better to solve clinical problems, healthcare problems than the doctors and nurses who are out there doing that? So what has changed in recent years that maybe is kind of a roadblock for this to continue to happen?

Bruce Gingles: Yeah, I think you've identified a very important shift in technology, healthcare technology, because virtually all of the important medical devices that we count on today were originally conceived and first validated by the clinician taking care of the patient. They were, as you say, at the front line, at the bedside, it was their problem and responsibility to their patient that they were trying to solve. And some of the solutions to their own problems was subconscious, they often didn't know exactly what it was about a certain procedure or care event that was driving them crazy but a light would often go on in their mind to say, "We struggle with this. I think I have a way I could solve the problem." And once they had a design in mind, they could come to a company like Cook or any other and say, "I have the same problems that my colleagues have and this is what we face."

Bruce Gingles: And if they were the sorts of solutions to the problem that we had the resources to address that, if we had engineering skills in that area, if we had the right materials, that it was part of our strategic focus, then we could, as you say, begin with prototypes and do some early bench testing, do some validation work and we could find out pretty early and without a whole lot of money, whether this was barking up the right tree, whether this proposed solution could really make a difference.

Bruce Gingles: And yet today as you say, that's really changed. Our system today often doesn't trust the doctors to do the right thing for patients. There's a whole movement they call conflict of interest and because doctors might receive royalties on the sales of products for which they've earned a patent, those royalties are now held against the physicians in many cases. There's so much production pressure placed on the physicians by their hospitals that any time away from clinical care is viewed by many hospitals as coming at the expense of their own bottom line. So they want those doctors in front of the patients as much as possible and billing for their time. So if they take time out to develop an important new technology, the hospital may see that as a conflict of commitment or a conflict of time.

Bruce Gingles: Those are a couple of the things that have really shifted the enthusiasm by doctors of solving their own problems, and the types of barriers that they face. Because in the old days if they came up with an important product, the Foley catheter, the Swan-Ganz catheter, the Fogarty embolectomy catheter, these sorts of things that even had their names on it, were not like Lipitor and Plavix that have made up names, the names of our products are often that inventor's name, they could sort of be local heroes, they would be in the newspaper, and they would be known around the hospital. Whereas today, people often treat them sort of badly for being part of the process.

Jon Speer: Yeah, I worked on a lot of those devices where the doctor who was the inventor, they got credit pretty much in perpetuity, at least with the name of the product. It reminded me, you sharing that little bit reminded me of a story when I first started at Cook, I loved your approach to getting engineers sort of out of the engineering and into the field. And one of the things that I did early on was attend an anesthesia course down at Shands Hospital at University of Florida. And I remember I was trying to figure out where this cadaver lab workshop was, and I found that it was in the catacombs of the hospital. But I got down to this cadaver lab and I was a few minutes late, but the doctor was already talking to the med students, and they were going through emergency cricothyrotomy devices, emergency airway devices and there were three or four different products, and they all had physician names tied to them because the physician contributed to that innovation. And one of the students asked the doctor whom I didn't know who it was at the time, asked the doctor what his favorite or preferred cric device was and he said, "Well, it's the Melker cricothyrotomy device, which of course is a well-known Cook product.

Jon Speer: And later after the cadaver lab, one of the med students was kind enough to show me to the next spot and I said, "Excuse me, who was that doctor?" And she's like, "Oh, that was Dr. Richard Melker." So, and that was just one of those moments, but you kinda appreciate that this guy not only does he... He's not doing this for financial gain, he's doing this to save and improve quality of life and I've had a chance to interact with Rich quite a few times over the years since. And it's a little discouraging, I think, as a med device professional to hear that physicians might be a little disenfranchised today.

Bruce Gingles: Well, yeah, that's exactly right. It's coming at them with new policies. Two of them that I find especially troubling. One is that when we get FDA clearance on a product which is required before that product can be used in a human so we always have the FDA's greenlight before these go into patients. But once we've gotten that clearance or approval from FDA then we could at least in theory, launch anywhere around the world, that we had regulatory approval for. Well, but when we come up with a new product after working for several years now with an inventor, we don't want other people to try it until that inventor has signed off with Cook that that's exactly what they want us to make for them. And we have always sent those early products to the inventor for evaluation and as you'll remember, they would often call you and make subtle changes just even after you think it had been built exactly to their specification, but there were often little things, it could be the length or it could be the tension on a trigger, these sorts of things that they'd like to have refined before it goes to bigger groups.

Bruce Gingles: Today, when we go to send those to the inventor, their chair will often step in and say, "We don't want you to be the evaluator because you're involved with that company, you have a conflict." They want that evaluation to be done by a disinterested third party, someone who's medically qualified but doesn't have that mental image of the ideal solution. And without that passion to make that product the best it can be, most of those ideas die once it leaves the inventor's hands and goes into the hands of a disinterested person. So, separating the inventor from the evaluation of the early product is often a death stroke to the technology, it really impedes the manufacturer's ability to be true to that person's vision.

Bruce Gingles: The second is that in the old days when physician autonomy was so high, they could request products in their hospital and the hospital was usually very accommodating. Today, if we get these products on the market after years of work with them, when they make the request to bring it to their practice so they can do what you're talking about, help their patient which is really their motivation, they're told to go to the value analysis committee and present their case and a large percentage of those requests today are rejected, they know in advance that hospital may not buy the product they worked so long to develop, and part of the reason may be because the hospital doesn't want their faculties to have a conflict. So, for many physicians that they can't ultimately practice their art on their patients, there's very little incentive to spend the time developing it.

Jon Speer: Wow, that's... It's... I remember after I guess this was probably three or four years maybe or so into my career, we started to see a shift at that time, so this would have been early 2000 time frame, where there was a lot more layers that were starting to be infused in between the medical device companies, designing and developing products and the physician inventors. I don't mean this as a negative per se, but I think it has had a negative impact on the industry, but there was a lot more, I'll say, bean counter, so to speak, and people that were more about the finances, the cost of the technology that were looking to bundle different products and trying to get discounts and all these sorts of things. And that seemed to be, at least from my perspective on this topic, sort of the beginning of what we're seeing today, where now the people making the buying decisions for hospitals and healthcare facilities are pretty far removed from the practice of medicine.

Bruce Gingles: Well, that's right, yeah. There's a whole new jargon today about this at the federal level, and also by the states as well as the payer community. Decisions used to be based on clinical outcomes and the science and clinical trials that demonstrated which procedures and which methods were best for patients. That's still very important, but really a major consideration today is known by names like value-based purchasing or value-based care. Where the algorithms used to decide what technologies will be available and how patients pathway through the health system will go really depends on resource conservation and minimizing the expenditure. So people at the front line of care, the doctors themselves are now being instructed, "We not only want you to give us good outcomes with our patients, but we need you to help us control costs." And this does affect the types of technologies that get developed and used in the hospitals.

Jon Speer: I mean it seems like a misnomer, value-based healthcare, shouldn't that have... It seems like the patient should be a more part of that equation, but sadly that's not really the case.

Bruce Gingles: Yeah, I think some of this comes down to the idea of equity. That is if you have a fixed budget, if your hospital is only gonna have a certain amount of money to spend each year, and in order to do the best job for the most patients, there's this idea that that budget is a zero-sum game. That if you pay money to help this patient, that's money that can't be used to help another patient. I think that's a little dubious, because the economy of the health system and the outputs of the health system have simply grown over the decades, it's actually just much bigger today. So, our life expectancy is considerably longer than just seven years ago, up about 50% or 55% in just 70 years, a lot of that has to do with technologies. And as life expectancy has gotten longer, that's more lifetime to earn income, to build your business and to contribute to the economy. So our nations, the G8 nations, they are much wealthier and our standard of living has gone up enormously largely in direct relation to the longer life expectancy. So, as this whole pie of age and productivity and our economy has gotten larger, we then really do have more that we can spend and invest on continuing that trend, but at the moment we, I think tend to look at that pie as being quite fixed. And is again, sort of a zero-sum proposition.

Jon Speer: Folks, I want to remind you I'm talking to Bruce Gingles. Bruce, is the Vice President of Global Technology Assessment and Healthcare Policy for Cook Medical. I also want to take a moment to remind you that Greenlight Guru recently launched a brand new podcast, that's right, MedTech True Quality Stories. You wanna check that out wherever you're listening to the Global Medical Device Podcast, you'll be able to find MedTech True Quality Stories as well. I like... This is the best part of my job frankly, is to get to talk to people like Bruce and others that are guests on both podcasts because it's really about trying to change this industry and move it in the right direction, and I love hearing what Bruce is doing and some of the things that he's monitoring and evaluating because his role is to try to make sure that healthcare is moving in a direction that maybe it seems obvious, but it's really about getting it back to the patient.

Jon Speer: And I think that's really, really important. So be sure to go check out MedTech True Quality Stories as well. During episodes on the MedTech True Quality Stories, we have some inventors and entrepreneurs, and folks that are in the trenches at different medical device companies throughout the world, and they share some of their successes and some of their challenges, but definitely worth a listen. So Bruce, we've talked about some of the current landscape and situation, if you will, seems a little dire, your finger is on the pulse of what's going on. Are things gonna get better or are they gonna get worse on this topic?

Bruce Gingles: Well, I think that's the really $50,000 question and I'm sort of disappointed to say, I don't really know at this point. But there is certainly tension in both directions, pulling on this rope, and from more than two directions, actually. So I'd like to remain optimistic. I think that, particularly as the baby boomers like myself, get older and we start suffering our own failures, physical failures, I think we're inclined to put political pressure on a system, whether it's the government and its agencies, whether it's the industry and the lobbyists for industry, to make sure that the best care including new therapies that no one has even thought of yet today could potentially become available in our own lifetime or those of the next generation and the one behind them. One of the trends that I think is very interesting at the moment is we see a huge reduction in the number of new ideas that relate to therapy, ways to actually improve the outcome for patients.

Bruce Gingles: We see a much bigger number of ideas coming in on diagnosis. Monitors, wearables, digital technologies, we can measure and monitor so many things today, but we are not keeping up with the number of solutions to those problems. What procedure or what intervention will follow that newly accurate diagnosis that actually then cures a disease or mitigates an illness? And I hope that at some point we can get these two back in balance, so that the therapy can keep up with the diagnosis.

Jon Speer: Alright, so let me try to connect a few dots based on what we've chatted about so far. So the trend that you're seeing is a much higher emphasis, if you will, on diagnostic devices and technologies. A decrease of therapeutic technologies, which if we go back to what we were talking about a few moments ago, this is directly, I think tied to physicians being disenfranchised in some respects. The focus is more on wearing something, and it telling me some vital sign, or some information about my health, but there's disincentives that are in place and certainly from the healthcare policy standpoint, from therapeutics. It seems like there's been a little bit of disincentives as well from a regulatory policy standpoint.

Bruce Gingles: Yeah, that's right.

Jon Speer: And it's kind of just a bad situation. Yeah, go ahead. Sorry.

Bruce Gingles: Yeah, today the cost and the regulatory barriers for diagnostics tend to be much, much lower. It's faster, easier, and cheaper to develop software and digital technology than to develop Class III or even some Class II interventional invasive products. And so I think that because of the finances for entrepreneurs and even established companies today are quite tight and the hospital budgets are under enormous pressure and there's not a big appetite today in the big health systems to invest a lot of money even for very promising technologies. The shortest distance between two points often looks like a quick and easy wearable. And those are very helpful. I think knowing more about disease is great. But again, because of the timelines, the long timelines, and the higher cost, the high failure rate through the development process for the interventional products is just simply not keeping pace. And I hope collectively as a society we can address that.

Jon Speer: Yeah, I hope so too. And I know a lot of the folks that listen to the Global Medical Device Podcast that, they may be in startups or inventors or developing some sort of technology. And I know 'cause I've been there and I speak with a lot of folks who are in this situation, it is really, really, really difficult to raise funding for something that is perceived to have a longer more challenging path to market as well. So it's a whole ecosystem that probably needs to be revised and revisited anyway to see if there might be some opportunities to improve the whole situation. I'm gonna put you on the spot a little bit, Bruce. Is there any... Sometimes we look for a single root cause or more importantly maybe a single solution, and I don't think this is a situation where there is a single solution, but is there one item or one area where you see as maybe the bottleneck or the gating item that if we would open that up and be more progressive on our thinking and our policies on this one particular area that it would make a huge difference?

Bruce Gingles: Well, what I could suggest is if we can break these bigger problems down into smaller problems that are easier to tackle, and do those one at a time, I think we have a good chance of achieving progress. One of the things on the example we were talking about a few minutes ago, about the difficulty that inventors have in evaluating their own products, I think a simple solution to this and one I hope our system will carefully consider and one that's already being used in a few forward-looking academic centers would be to insist that that inventor be the operator during those evaluations on those prototype products. But in addition to the inventor, there would be a chaperone assigned by the service chief or the chair who doesn't report to the inventor, they're not subordinated to the inventor. They report directly to an independent person.

Bruce Gingles: And that second person, that chaperone would be present for two purposes. They would make sure that the patients that get that new technology are appropriate for the technology, that they're not being railroaded into a trial that only because the inventor is enthusiastic. And the second reason that they would be there would be to make sure that the records of those cases that are performed are truly accurate, that an inventor can't think to themselves how great this was when in fact there could have been some problems that occurred and this person would have an objective, second set of eyes that would make sure that whatever reports are generated both to the medical record and eventually maybe to publications in the clinical literature were entirely accurate.

Bruce Gingles: And by having a supervisor who does not interfere with the performance of the procedure, but make sure that certain state guards are implemented, now you've avoided all the potential for conflicts of interest, you protected the patient by having a second party there that's there to serve their interests, and yet, you're also permitting that inventor to do the work that they're most qualified to do, that is the inventing itself and feedback directly to the engineer on the proper device improvements. I think that system could make an enormous difference for the way we develop medical devices.

Jon Speer: It seems pretty simple at its core. I know that there's some nuances of course to figuring that out and it's encouraging to hear that there are some facilities that are starting to embrace this, so that's really encouraging. What can we do? What can I do? What can Greenlight do to help spread the word or influence change in a good way on this topic? Or what can the audience do for that matter?

Bruce Gingles: Well, I think you're already taking a great step. I think one of the things you might consider would be to have a panel on one of your programs and on that panel, you could invite people that have pro and con views about this and people who are in policy making positions and I think if they were able to debate these issues on Greenlight Guru and make these topics public, it might synthesize our thinking about these a little better and where we could then eventually come up with more rational policy about how to address this. And I think your program does an awful lot of good to bring these ideas forward and then let thoughtful people play around with the policy side.

Jon Speer: I appreciate you saying so, and that's a really great idea. I might lean on you for some help putting something like that together in the future, but really great idea. Bruce, before we wrap up this episode of The Global Medical Device Podcast, any parting thoughts or words of wisdom or tidbits and nuggets of information that you think are important for our listeners to leave with?

Bruce Gingles: Well, I can't think of anything else at the moment, Jon. I wanna thank you for spending time today and I really enjoyed talking to you and I certainly look forward to our next airport meeting [laughter] and thanks very much for speaking with me today.

Jon Speer: Oh. Absolutely. Folks, this has been so exciting for me to get to talk with Bruce. Bruce is a guy I've looked up to for so many years. He really helped shaped how I function as a medical device professional, just really grateful to his guidance and mentorship early on in my career. Bruce is, again, with Cook Medical. He is the Vice President of Global Technology Assessment and Healthcare Policy. He's also an author. He has a book out there. My copy is on its way to my doorstep now. It's called Medical Innovation: Concept to Commercialization. I haven't read it yet. But I am sure that it is fascinating. I'm sure that it shares what's important about new technology and working with physicians and getting these devices that are gonna save and improve the quality of life into the hands of those who could do something about it. So Bruce, thank you so much for being my guest.

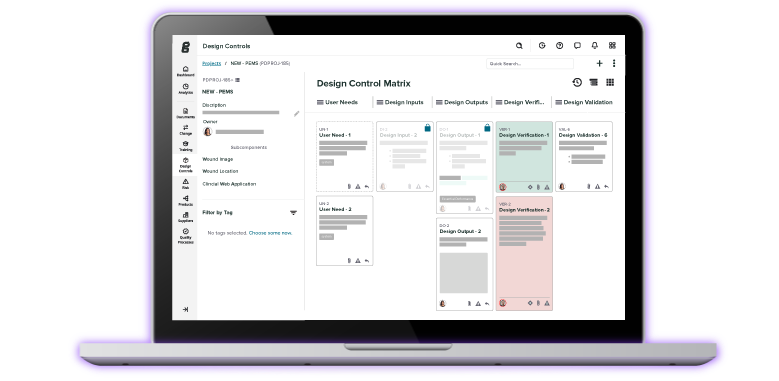

Jon Speer: Folks, certainly there are challenges that we face on a number of fronts as medical device professionals, whether it be figuring out how to navigate the treacherous healthcare policies that are in place in some cases, or whether that be regulatory pathways, whether that be making sure we have true quality systems in place. Certainly Greenlight Guru is here to help. We have an EQMS software platform that is designed specifically for and exclusively by medical device professionals. That's the only one on the market that can make that claim. So I would encourage you to go check out what we're doing at www.greenlight.guru to learn more. If you'd like to see a demo and learn more about the software platform and how it can streamline your product development efforts and improve your quality efficiency, certainly something that you should check out. Folks, thank you so much for listening to the Global Medical Device Podcast. And yes, be sure to go check out the new podcast MedTech True Quality Stories, as well. As always, this is your host, founder, and VP of Quality and Regulatory at Greenlight Guru, Jon Speer.

ABOUT THE GLOBAL MEDICAL DEVICE PODCAST:

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Etienne Nichols is the Head of Industry Insights & Education at Greenlight Guru. As a Mechanical Engineer and Medical Device Guru, he specializes in simplifying complex ideas, teaching system integration, and connecting industry leaders. While hosting the Global Medical Device Podcast, Etienne has led over 200...