Why the Conventional Wisdom Regarding ‘R’ and ‘D’ in Medtech Product Development Is Wrong with David Amor

Today on the Global Medical Device Podcast we have a very interesting and highly debated topic for you around research vs. development for medical device companies.

Jon Speer invites guest David Amor to join the show as the two touch upon a lot of the points in that post (which I encourage you to go read after listening to today’s episode) and really dig into why the conventional wisdom regarding ‘R’ and ‘D’ in medical device product development is often wrong.

David Amor is a medtech/biotech consultant and mobile health entrepreneur. David is the founder of Medgineering, a consultancy specializing in implementing new quality systems, design control processes, and risk management for both startups and larger companies.

Listen Now:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some highlights of this episode include:

- Why should you start design controls early in development?

- Are your thoughts about research wrong?

- Will doing design controls early slow you down?

- When do design controls ACTUALLY start?

- How to view design controls as more than a paperwork heavy process.

- The shift in traditional R&D roles.

- What outcomes you should be focused on BEFORE research.

Links:

FDA Design Control Guidance Document

When does the ‘R’ end and the ‘D’ begin for medical device companies?

Transcription:

Announcer: Welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Jon Speer: Hello. This is Jon Speer, the founder and VP of Quality and Regulatory at greenlight.guru and welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast. Today, we have an exciting topic. Yeah, I know, every topic we share with you is exciting, but this one is one that's really fun for me. It's something that I've been dealing with throughout my entire medical device career that spans well over 17 years now and that topic is this: Research versus Development. You're gonna wanna listen to this because the standard practice, the conventional wisdom, around research and medical device product development, I'm gonna tell you folks, it is wrong

Jon Speer: There's nothing wrong with starting your design controls early and often in your product development efforts. Joining me today in this podcast is a familiar guest, David Amor. David is a medtech/biotech consultant and mobile health entrepreneur who founded Medgineering, a company focused on remote compliance, regulatory & quality systems consulting for larger companies and start-ups. David is a graduate of the prestigious Innovation Fellows program at the University of Minnesota's Medical Device Center. David was named a Top 40 Under 40 Medical Device Innovator in 2012 and a 35 Under 35 Entrepreneur in 2015 by Minnesota Business Magazine.

Jon Speer: David and his company, Medgineering, provide a lot of quality system services that are based out of the Twin Cities in Minneapolis, Saint Paul. They use remote model to save clients time, money, and procurement headaches. You can visit them at medgineering.com, M-E-D-G-I-N-E-E-R-I-N-G dot com. David's company also recently founded QuickConsult and it's a great platform. You should check that out as well, myquickconsult.com. So sit back, relax, listen to why you need to focus on capturing your design controls while your thoughts about research might in fact be wrong.

Jon Speer: Hello, this is Jon Speer, the founder and VP of Quality and Regulatory at greenlight.guru and this is another exciting episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast. Today, we brought back, David Amor. David is with Medgineering. David, welcome to the show.

David Amor: Morning Jon. Thanks for having me again. Always been.

Jon Speer: Absolutely, yes. So I think we promised our listeners the last time that you and I were gonna get together and have a little bit of a discussion about research versus development.

David Amor: That is accurate. So let's do it.

Jon Speer: Let us do it. Alright, so I'll just start with a couple of comments and rip apart anything that I say or share from different points of view, we're just kind of free flowing here. We're just sharing a few ideas, thoughts, and so on, and I guess that's a good place to start. I always like to give those listening, towards the very beginning of our discussion on these podcasts, a tip that they can use. And let's start with this. I hear people say to me all the time, "Jon, Jon, that design control stuff, I can't do that too early because it's going to slow me down. I need to wait and target a certain point in my project before I start capturing design 'cause I can just stay in research for as long as possible." So, David, what do you think about that?

David Amor: Yeah, I think that's interesting. The other addition to that, but I'll say, and I face the same thing with clients and customers all the time, but I think the other thing that you say, that you get is, "Hey, David, when do we start design control? When is this design control stuff applicable?" And one of the hilarious things about all this is the FDA itself, if you look at their design control guidance, their infamous design control guidance from 1997, one of the first things that it says in that guidance is, "Some manufacturers have difficulty determining when research ends and development begins," and when I read that, I was like, "Yeah, exactly, I mean, no kidding."

David Amor: So, I think, you're right. I think one of the things that company struggle with is, what falls under design controls? What falls under kind of feasibility proof of concept stuff? And I think the easiest way, the philosophy that I think is the best way of approaching this is, design control starts when you say it starts. Design control starts when your product is ready to be proven to the world, the FDA that it is under a state of control, so anything that's done prior to that, any sort of feasibility, proof of concept, vetting out the IP, vetting out the technology, we're less concerned, regulators are less concerned about that aspect versus having a vetted concept fully developed under the design control requirements in 21 CFR 820.30 and then really validating it and getting it to market.

David Amor: So really, in short, your company determines when design control starts, and I think your comment about, you know, "Oh, we have to spend way too much time or we wanna spend more time in research because we don't wanna be subject to design controls," I think that's the perspective only if you look at design controls as a paper work exercise. If you look at design controls as more of a needed part of your product development process, you'd be surprised at how effective it can be at catching issues. I mean I was just working with a company a few weeks ago where one of our preliminary design reviews yielded the fact that we did not fully characterize the product with design inputs.

David Amor: So one of the things that we had to do after that design review is go back and say, "Are there any standards that we're missing that might have some design input requirements that we need to test?" And that was something that was yielded in a design review. And a lot of companies, unfortunately, treat that designer review as a, "Oh, let's just check the box. We did our due diligence. Call it a day." So, yeah, I mean long story short there, I agree it's one of those things that it's not very well defined within a lot of organizations.

Jon Speer: Yeah, as you said, your piece about that, I just found myself nodding my head. Of course, this is an audio piece and not a visual piece. The design input comment that you offer there towards the tail end, I can't stress that enough to those who are developing medical devices. The success of your product is going to live or die based on how well you've documented and defined your design inputs.

David Amor: Yep, absolutely.

Jon Speer: There's no question about that.

David Amor: Absolutely.

Jon Speer: Alright, so let's, I wanna pick on a couple of things that you offered and your explanation. So the first thing I'd like to throw out is, this scenario that I've come across quite a bit and I'm sure you've come across quite a bit as well. And we'll kinda start with this concept that design control, this conventional wisdom that's out there and, by the way, conventional wisdom is nearly always wrong. But the conventional wisdom that's out there is that design controls are a large amount of paperwork and documentation and it's going to slow me down. Okay? So we'll start with that premise. And like, how many times, David, have you said the word design control to an engineer or somebody that's involved in product development and they cringe like...

David Amor: They freak out.

Jon Speer: Yeah, they freak out, they're just like, "Oh my gosh, I can't do that. It's too much time, effort, and energy." So I'm gonna start with that kind of, now that I've framed you, I'm gonna throw this thing at you. I've worked with a lot of people who have that mentality or that approach to design control. They see it as this pain. So they go through, they design, they iterate, they don't always write anything down but they're focused may be more on the prototyping piece and what have you, and then they get really very far along and they've a lot of prints, they've started machining or manufacturing and building all these prototypes and they get to the point where they're ready to do their formal testing at IEC testing or boxing it up for biocompatibility or what have you, and then they start getting these results back and then they're like, "Alright, now, we gotta hurry up and go do our design controls." So what do you think about that?

David Amor: Yeah, I think the easiest way to answer that is, design controls, in a nutshell, is good engineering. So all of that work that you're describing literally just tweaking the terminology and tweaking the approach to how you do things in a very slight sense, in a more controlled fashion, let's be honest, it's more controlled. However, all of that is good engineering. I mean everything you just described, right? So testing, validation, creating testing plans, writing down what your product needs to do, in a sense, what your product needs to do is a requirement that is design input section of the design control requirements anyway. So I think, in a nutshell, your good engineering principles, which you should be following as an organization anyway, I mean honestly, it's just a matter of applying those engineering principles within the framework that the design controls regulation establishes.

David Amor: So, instead of just kind of getting together with the team and saying, "Hey, does the feature look good?" "Yeah, we're good to go." "Are you good to go, Tom?" "Are you got to go, Dave?" "Yeah, let's move forward with it." Make that a design review. Make that something where you're sitting down with the team, you have actually an independent reviewer, who is not really involved with the project to kind of give you that unbiased opinion. You document that and you really come up with all those action items. You've just done a design review. You don't have to freak out about it. It's not something that's gonna take 700 pages of documentation. It's really about, how you apply those principles within the context of design control.

David Amor: So I really do think that one of the things that a lot of companies struggle with is just like you said, they hear the term, "Oh, we're entering the design control stage or everything we do moving forward is under design control." Why is that such a big deal? I mean if you're doing your due diligence, if you're doing the right thing, you should be operating within a design control framework anyway, so yeah, that's my initial reaction to that scenario.

Jon Speer: Okay. And I think the reason, I'm gonna speculate for a moment. I think sometimes the reason why people freak out about entering design control too early is the root cause of that probably has to do with the processes and procedures that are in place at their company. I would speculate that those processes and procedures that define their design control process probably make it somewhat prohibitive to iterate and change after you're in a state of "design control".

David Amor: Yeah, I know, that's absolutely the case most of the time. And I think one of the other points to that is, a lot of companies, they basically have this huge proof of concept stage, right? They have this feasibility, they're doing a bunch of testing on the technology, they're kind of vetting the technology, then they start doing testing and then literally, like you said, they get through a six or seven or eight months effort that's "proof of concept" and they're like, "Oh, you know what, we're gonna just do a design verification test and call that our design control process, and voila, we're done," right?

David Amor: So again, it becomes a paper work exercise whereas, if you leverage... Let's just take what the FDA's perspective is on this, right? So they indicate clearly again that same guidance that prototypes are not sufficient for testing under design controls, right? So when you're doing testing as a quick example, for your product, right? So you're doing design verification testing. You need to make sure that you're testing units that are developed under "production equivalents" right? So processes that are gonna be commercial processes. The bomb has to be pretty similar to what the bomb is gonna be commercially.

Jon Speer: Bomb bill of material, just in case.

David Amor: Yeah, exactly. Bill of materials, we don't wanna get in trouble with any federal agencies here. So, yeah, those are the type of things that that's where that level of control is a little bit different and the development stage in your design control stage versus your research, your R part. And I think it's very clear within the guidance. I mean there's literally something within the FDA guidance that's called the concept documentation, and that could be those inputs from marketing, those inputs from clinical, and those are really used as the basis for preliminary design inputs, preliminary research into your product.

David Amor: Once those are "hashed out" and really nailed down and you have a product concept that you think is feasible, that's when you can really say, "Hey, we've proven this concept to ourself, to the company. We're comfortable that this is a feasible technology, the market is there, all the business stuff is taken care of, our actual product is feasible, the technology is sound, we wanna develop this into a medical device." And that's the key difference. In that R phase, in that research phase, you're proving to yourself that this thing is gonna work. The technology is good. The research that went behind getting the technology created is good. When you're ready to turn that technology into a medical device, "medical device" per section 201h, that's when you really are ready to enter design controls.

David Amor: And that's not something that's clearly delineated. You know, often companies will have a proof of concept stage. They'll have a feasibility stage. And then once they end that stage, they'll go into a "definition" or development stage where design controls kind of starts getting implemented, and that's really not something that I can answer, that Jon you can answer. It really is dependent on the company and how they approach the design development process.

Jon Speer: Totally. And I think just at one point and then I'll shift the discussion slightly. I know, David, in your explanation, you're referencing an FDA guidance document, just want to clarify here, I'm pretty sure you're referring to the FDA's design control guidance document. It's a really good document. It really is. FDA puts out a lot of guidance documents. Some of them, I'm just gonna say, are better than others. And I think the design control guidance document has been around for a long time, but it is still applicable today, and it's really good. So I do encourage people to check that out. But everything from an FDA perspective, on a design control topic, I just wanna make sure this is also clear because we have people listening to this all over the world.

Jon Speer: The FDA view on design controls is consistent and in alignment with ISO 13485 and what's even more important for everyone to realize is, ISO 13485 has been published, a new version has been publish just a few weeks ago. So there is a 2016 version of that. And from everything that I know and I've read and learned about this new ISO 13485, it's even more aligned with the FDA's 21 CFR 820.30 design control regulations. It's almost a mirror image. So I think that's important for people to realize.

David Amor: Yeah.

Jon Speer: Okay. So let's talk a little bit about this word 'research' and all the different permeations and connotations and all that sort of thing. The classic word is or the description of the product development process is research and development and that word research I think is a key thing for people that kinda understand. And you said it very well just a few moments ago. What that means to each company is going to vary probably quite a bit from one company to the next. Some people call it research, some people call it feasibility, some people call it proof of concept. There's a lot of words that are used to describe that research. And in my experience, I have really very seldom worked in an environment or with a company, where there was really pure research involved. Usually it was more taking ideas and concepts and kind of refining those and I don't know, is that research or is it something else? What do you think?

David Amor: Yeah, that's a good question. Just practically speaking, you can see some organizations shifting away from calling their product development engineers R&D, right? So even at some of the large companies who I will not name, but you'll see some groups now just being called research or fun and research, or concept research, and then the other folks that are involved more on the product development side, in terms of actually developing the product once it emerges out of this research activity from a feasible product into a fully functional safe and effective medical device are being called technical development or product development or something else.

David Amor: So that traditional R&D role which, unfortunately, still gets thrown around in Frost & Sullivan reports and all these other reports. When you look at manufacturing versus R&D and all these different considerations, I think that's really shifting. I think people are really starting to understand that research in the beginning is truly just that. It's researching the IP, researching the concept. For example, if you have a... A lot of companies... I kind of bucket development into two different categories. You have the evolutionary products where you might have a catheter, let's say, and the next generation is an upside catheter, right? So that's an evolution.

David Amor: The design change there is fairly insignificant. You might have just a few tests that you need to do to make sure that the increased size doesn't really change the performance of the product. And then you have those revolutionary changes where you have a brand new piece of technology, a brand new IP, that needs to be vetted before you can even consider plugging this into your product pipeline or portfolio.

David Amor: So if you look at those cases, there's definitely gonna be a lot more of the R, of that research, in that second case, right? So you're gonna have to have a team that's dedicated to vetting the concept. That can be anything from bench top testing early on, animal studies. Really that preclinical piece, that's gonna demonstrate that this technology is, the technology itself is really safe and effective. Once you demonstrate that that technology is safe and effective in that "research" part of this puzzle, that's when you can almost present that to the executive team and say, "Hey, look, this technology works." Right? The core technology, the core competency being evaluated, it works. This laser will not kill you. This laser actually degrades tissue accurately.

David Amor: Now it's taking that platform, that core technology, and sticking it into a medical device that's a regulated medical device and that's where that D comes in, right? So I think that's where the companies are starting to split that up. Because traditionally, it used to having, like you said, Jon, it used to have some people who are in R&D that were doing everything from going to look at, you know, going to do prototyping at the very basic level, going up to meet with key opinion leaders and do a lot of that work. And they were following their product all the way through design transfer. And now oftentimes, you'll have those two things separated within a company. Is that a good thing? Is that a bad thing? You know, I don't know. I'd be curious to hear your thoughts on that.

Jon Speer: Yeah, I had a stuff several years ago with a larger company and we were starting, at that time, to make that particular shift and the perception was interesting. The perception from a lot of engineers is they really wanted to be in that research group because they felt as though it was kind of, I don't know, more engineering focused and a little bit more free form and a little bit more creative? And maybe a little less structured from what would be required from a documentation standpoint. And at that time, I was getting more involved with evaluating the overall organization, the design control practices, and I was like, "Hey, guys, look, I understand that that's the perception that you have about research. But if that's the reason you're going there, then you're not doing the D side of our business any favors because if you're thinking that you're just gonna go and research and just tinker and play and just be creative, you gotta be focused on an outcome," and you articulated that fairly well.

Jon Speer: One of those outcomes is demonstrating that your concept or idea or what have you have merit. And you may do that, like you said, through some animal studies or other bench studies, preliminary bench studies, that say, "Okay, we've done some research and we've come up with a possible path forward for this particular product or device or what have you." I think the other thing that's a key to understand about that the R versus D pieces in addition to presenting sort of a business case that if you're in research, that's an excellent time to really start identifying some key pieces to the development side. And those key pieces will be an understanding from the view of an end user, whether that be a doctor or a patient receiving this product, what is important to them. That should be a major objective of research, whether there are separate groups or combined.

Jon Speer: Another key part of that should be, you're really laying the foundation for those design inputs. I'm not suggesting that you exit research with a fully vetted fleshed out list of design inputs. But I think you have to be very focused on some key deliverables as part of that research process. Now you can certainly be creative but you need to come up with maybe three or four items that are documented, that are results oriented, that then can now be smoothly transferred into your development side of the equation.

David Amor: And that's just, I mean that's just it, right? So I think one of the... You brought up a good point. One of the things I see a lot of is the design inputs documentation at a company often it's kind of a mixed bag of user inputs, then marketing inputs, then clinical inputs. You have regulatory. All these different functional groups. So one of the things that I like to see usually or that I usually recommend when I'm working with a group is I like to sequester kind of that pre what the FDA again called concept documentation is really high level inputs and they actually use marketing as a good example that, hey, marketing will often say something, but that in itself is not a testable verifiable design input requirement.

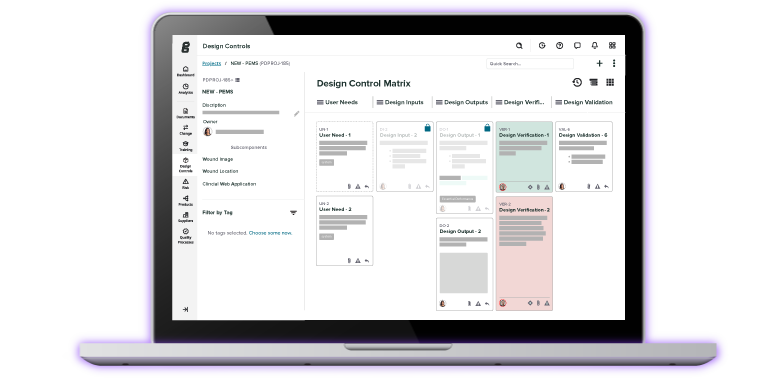

David Amor: So one of the things that I implement a lot when I'm working with design control products or processes is I like to have a separate, you know, catch all for all of these things that come out of research, like you said, Jon. And then from that bucket of inputs from again regulatory marketing, all the different groups, really create a user needs or a need document that summarizes all those needs that becomes traceable to the more technical design input requirements which are gonna form the basis for your design. So really having that as a nice traceable process, it not only makes it practically simple, right? So start thinking about, "Okay, this is all the stuff we learned in research that we need to really consider while we're developing this into a medical device," but also from a design history file perspective, you start thinking about, "Okay, what am I gonna submit to regulators? Am I gonna submit everything that was in research?"

David Amor: Probably not, because a lot of that was, again, just kind of throwing things against the wall to see if they stick. But some of those key decisions that were made in that research phase that will drive rationale or reasons for design inputs, those are some of the things that I like to usually see in a design history file, and that's really critical for submission obviously. So, yeah, I think that's a really good point in terms of what comes out of research that's still being used for design history files. I think that's kind of the summary of what I would say would be the case.

Jon Speer: Alright, well, David, I know we're just skimming the surface on the topic of R&D and how that applies to design controls in medical device product development, and I'm sure we'll have another session soon where we may go down a different branch, or twist, or turn on this and other related topics. So, before we wrap up today, let everybody know a little bit about you and about Medgineering, and where they can find out more information about how to get a hold of you.

David Amor: Sure. So we are a company called Medgineering, www.medgineering.com. That's M-E-D-G-I-N-E-E-R-I-N-G dot com. We do a lot of work in the quality and regulatory space. Obviously, a lot of our work is in implementing new quality management systems, design controls processes, risk management. Some of our key areas of expertise over the last few years have been in combination products, so working a lot with drug device delivery manufacturers as well as other combo products, and we've recently launched a platform which is really cool called QuickConsult, www.myquickconsult.com. And essentially, it's an online consulting platform.

David Amor: So, we pair up experts with company startups or large companies alike, and really allows them to do the interaction, the consulting engagement online. So, it makes it a lot easier, keeps the cost low, and really allows a customer to have control over their consulting engagement by picking the person that they want, looking at references, all that is done online. So, that's something that we're really excited about and hopefully can help a lot of companies understand these design control processes and applying them to your organization.

Jon Speer: Very cool, very cool. Well, David, again, thanks for being our guest on this episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast. This is Jon Speer. If you're having some design control questions, you can certainly contact David. You could also contact me in greenlight.guru. Greenlight.guru has developed a software platform to help you manage not only your documents and records and your quality management system, but we've optimized a workflow that makes capturing, managing, maintaining all of your design control activities pretty simple and easy. It also incorporates all of your design and development activities and integrate that with an ISO 14971 risk management platform as well. This is Jon Speer. I'm the founder and VP of Quality and Regulatory at greenlight.guru and this has been another episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast.

About The Global Medical Device Podcast:

![medical_device_podcast]()

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Nick Tippmann is an experienced marketing professional lauded by colleagues, peers, and medical device professionals alike for his strategic contributions to Greenlight Guru from the time of the company’s inception. Previous to Greenlight Guru, he co-founded and led a media and event production company that was later...