The Clinical Evaluation Literature Review Process: Identifying and Appraising Clinical Data (Part 2 of 4)

.png?width=800&name=The%20Clinical%20Evaluation%20Literature%20Review%20Process%20Identifying%20and%20Appraising%20Clinical%20Data%20(Part%202%20of%204).png)

A successful clinical evaluation hinges on your ability to find and appraise the data you’ll need to demonstrate your device’s safety and performance.

However, it’s also one of the more difficult and time-consuming aspects of the clinical evaluation process. That’s why we’re devoting this article—part two of our four-part series on the clinical evaluation of medical devices—entirely to explaining the process behind gathering and appraising clinical data.

In this article, I’ll be covering the different types of clinical data, how to create a literature review protocol, and how to appraise the clinical data you find. We'll also cover how to prepare your Clinical Evaluation Report (CER) so it complies with MDR.

WHAT TO EXPECT IN THIS 4-PART SERIES |

|

Part 1: Clinical Evaluation of a Medical Device: Creating a Process and Establishing Equivalency |

| Part 2: The Clinical Evaluation Literature Review Process: Identifying and Appraising Clinical Data (this article) |

|

Part 3: Performing Data Analysis for Your Medical Device’s Clinical Evaluation |

|

Part 4: How to Create a Clinical Evaluation Report (CER) under MEDDEV & MDR |

Identify where you’ll obtain clinical data for your evaluation.

Your clinical evaluation will be based on both direct and indirect data.

Direct data is data that has been generated by your device, such as the data obtained from pilot studies or clinical trials. If your device is Class III or a Class IIb implantable, then you will be required to conduct clinical trials on your device and will generate direct data that way.

Direct data also includes registries and publicly available data on your device. You’ll also generate direct data from your postmarket surveillance activities, though this won’t be available to you during the initial clinical evaluation process.

Indirect clinical data is data that has been generated by an equivalent device, which is why it’s important to establish equivalence early on. The decision to claim equivalence (or not) will be one of the factors that affects your literature review.

The literature review is the means by which you obtain indirect clinical data. Many companies, especially if they are evaluating a low-risk device, will rely heavily on data from literature searches, as they won’t be carrying out any clinical trials.

The goals of your literature review

Your literature review will have two outputs:

-

Literature on your device and the equivalent device (if applicable).

-

A review of the “current knowledge/state of the art” necessary for appraising and analyzing the clinical data from the literature on your device and any equivalent devices.

Let’s talk about the term “state of the art” for a moment. MEDDEV 2.7.1 Rev 4 defines “state of the art” as the:

applicable standards and guidance documents, information relating to the medical condition managed with the device and its natural course, benchmark devices, other devices and medical alternatives available to the target population.

Your device does not live in a vacuum. The benefit-risk assessment of your device in part depends on what alternatives to your device exist, and whether they pose more or less risk to a patient than your device. Put simply, “state of the art” refers to the best practices currently available in the marketplace, and your clinical evaluation must take into account how your device compares to those alternatives.

Create your clinical evaluation literature review protocol

Once you know the outputs you’re looking for, it’s time to create a plan to obtain them. This means crafting a detailed protocol for your literature review. This isn’t an instance in which a Google search will turn up what you need; the literature review must be a systematic process.

Annex 5.3 of MEDDEV 2.7.1 Rev 4 includes a full list of what should be included in your search protocol, but here are a few pointers to keep in mind as you create your literature review protocol:

-

Your protocol will need to clearly define the objectives of your literature evaluation. For instance, if there are particular risks related to your device that have been identified, one of your objectives may be to search for literature containing information on that risk. On the other hand, you might also search for literature pertaining to any clear benefits that have been identified with your device.

-

You’ll need to designate specific terms that you’ll use in your search. If your terms are too broad, your search may return thousands of articles, many of which will be irrelevant to your clinical evaluation.

-

Your protocol also needs to establish which sources of information will be used for searches, and you need to be consistent about using those sources. That means applying the same search terms to several databases, such as PubMed, MEDLINE, or Embase.

-

Set up your search so that you get both titles and abstracts for the articles. The abstract will help you better determine whether you should acquire and read the full text of the article. This is what tends to make the literature review process so time-consuming—you need to read all of the relevant literature that your searches turn up.

Keep in mind: you cannot pick literature that will support your device and discard those papers that may be harmful to your cause. This is part of the reason you’re required to create a search protocol in the first place—it allows your Notified Body to retrace your steps if they have concerns about your literature review.

Appraise the clinical data from your literature review

Even a literature search with specific, defined terms can turn up hundreds of results. That’s why it’s important to have a systematic approach to appraising which results you should use and which you should discard. Generally, you want to consider four factors:

-

Suitability - Is this based on our device or an equivalent device?

-

Applicability - Is this about other devices that use the same technology?

-

Population - Is the population similar to the population we believe our device will treat?

-

Quality - Is this literature published in a peer reviewed journal? Is the data generated from a randomized double-blind trial with a placebo, for instance?

That last point, quality, is a big one. In MEDDEV 2.7.1 Rev. 4, Annex 6 offers a number of points for concern you should look out for including:

-

A lack of information on elementary aspects, such as methods, patient population, side-effects, or clinical outcomes.

-

Statistically insignificant data or improper statistical methods.

-

A lack of adequate controls leading to bias or confounding.

-

The improper collection of mortality and serious adverse events data.

-

Misinterpretation of data by the authors, such as when the conclusions they draw are not in line with the results section of the report.

-

Any illegal activities, such as clinical investigations that were not conducted in compliance with local regulations.

Once you’ve eliminated any results with these types of flaws, you’ll need to weigh the importance of the different data that you’ve obtained from your scientifically valid sources.

At its most basic level, this means assigning a higher weighting to high-quality data that is most relevant to your device, and assigning a lower weighting to less relevant data. If you’re unsure about how to weight your data sets, Appendix III of MDCG 2020-6 provides a suggested hierarchy for clinical data that should be helpful.

It’s important to note that the appraisal of data may require someone with a specialized skill set, such as a statistician. In fact, it’s highly unlikely that one QA/RA professional can handle an entire clinical evaluation by themselves, and I certainly wouldn’t recommend trying.

Finally, your appraisal of the data must be documented, and it should be presented clearly enough for a third party to review your decisions.

Up next: Stage 3 of clinical evaluation — analyzing your clinical data

Once you’ve gathered and appraised the data you need, the next step is analyzing it to determine whether or not it demonstrates compliance with clinical performance and safety requirements. Check out part three of our series for an in-depth look at the data analysis stage of your clinical evaluation.

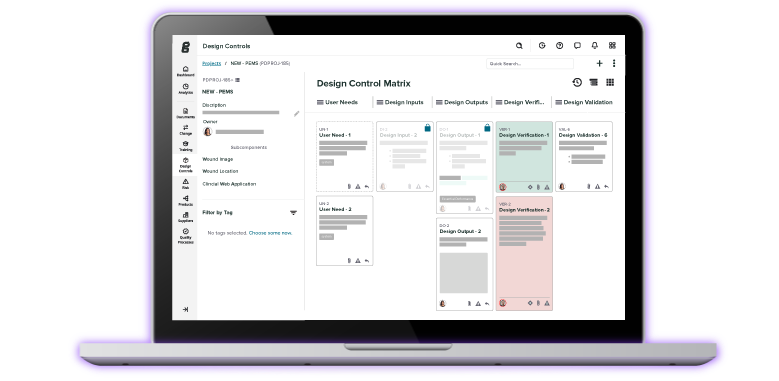

Looking for an all-in-one QMS solution to advance the success of your in-market devices and integrates your post-market activities with product development efforts? Click here to take a quick tour of Greenlight Guru's Medical Device QMS software →

Niki Price is a Medical Device Guru who has spent her entire career working with different types of medical devices. She began her journey in production, which is where she discovered how important and fulfilling this line of work was to her! Spending time in both Quality and R&D, she enjoys the product development...

Related Posts

Clinical Evaluation of a Medical Device: Creating a Process and Establishing Equivalency (Part 1 of 4)

Performing Data Analysis for Your Medical Device’s Clinical Evaluation (Part 3 of 4)

How to Create a Clinical Evaluation Report (CER) under MEDDEV & MDR (Part 4 of 4)

Get your free eBook

The Ultimate Guide To Clinical Evaluation Of A Medical Device In The EU

%20The%20Ultimate%20Guide%20to%20Clinical%20Evaluation%20of%20a%20Medical%20Device-1.png?width=250&name=(cover)%20The%20Ultimate%20Guide%20to%20Clinical%20Evaluation%20of%20a%20Medical%20Device-1.png)

%20The%20Ultimate%20Guide%20to%20Clinical%20Evaluation%20of%20a%20Medical%20Device-1.png?width=180&name=(cover)%20The%20Ultimate%20Guide%20to%20Clinical%20Evaluation%20of%20a%20Medical%20Device-1.png)