.png?width=4800&height=2400&name=podcast_standard%20(1).png)

What are the most common problems for medical device companies with their CAPA process?

Today, frequent guest Mike Drues, president of Vascular Sciences and host Jon Speer are going to dive into that question and get you the answers you need and want.

Listen Now:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some highlights of this episode include:

- Why the CAPA process is such a big issue within the industry and why Jon wrote a column on it.

- What businesses are doing instead of focusing on CAPA and why this is one of the major problems with the process, as well as why a cross-functional team is vital.

- How a management review board can help when it comes to regulations, as well as the fine line between micromanagement and giving a company too much latitude when it comes to meetings with the management review board.

- Being reactive vs. being proactive.

- Why it’s important to respect, but not fear, the FDA. Mike also talks about who you should fear when it comes to liability.

- Thoughts on whether the CAPA is used too frequently or not frequently enough.

- Thoughts on establishing criteria and giving companies the responsibility to establish that criteria themselves.

- The root cause of problems with the CAPA process and what companies can do about it.

Related Resources:

The 5 Most Common Problems With Your CAPA Process

Memorable Quotes from this episode:

“Does your CAPA process need a CAPA?” - Mike Drues

“If you just focus on compliance, that makes you average.” - Jon Speer

“Don’t think about it as a CAPA. Think about it as a PACA... The more prevention, the less correction.” - Mike Drues

TRANSCRIPTION:

Announcer: Welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast, where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go, to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Jon Speer: What are the five most common problems with your CAPA process? Well, good news, Mike Drues from Vascular Sciences and I dive into this topic on this next episode of The Global Medical Device Podcast.

Hello, and welcome to The Global Medical Device Podcast. This is your host, founder, and VP of quality and regulatory at Greenlight Guru, Jon Speer. And want to welcome a familiar voice and guest that has been on The Global Medical Device Podcast a few times before. I want to welcome Mike Drues, president of Vascular Sciences. Mike, good morning.

Mike Drues: Good morning, Jon. Thanks for the opportunity to have this conversation with you and your audience.

Jon Speer: Mike, you know that I circle these dates on my calendar, because you and I get to have a good time when we talk about these various topics for the podcast, so you got it.

Mike Drues: Well, you're right, regulatory and quality do not have to be boring topics.

CAPA PROCESS

Jon Speer: I mean, I love it. I know you love it. And for those who don't love it, I would encourage you to maybe get hold of Mike and myself, and find out maybe what we're drinking or why it's so exciting to us. But you know, it's kind of a mindset thing that I know, that we've arrived here at different paths, but it is great to talk to you.

And Mike, I was hoping that today we can dive into topics that, I think, a lot of people in the industry struggle with. And I guess, broadly speaking, it's CAPA. And I thought we can, maybe, talk about some of the kind of problems that people have with their CAPA process. What do you think?

Mike Drues: I think that's a terrific topic, Jon. And as a matter of fact, I'm looking in front of me at a column called The Five Most Common Problems With Your CAPA Process. And low and behold, it was recently published by you.

Jon Speer: Yeah.

Mike Drues: So, why don't we start out with a broad questions, Jon? Why is this such an important issue for this industry? And what was your motivation for writing this column?

Jon Speer: Well, I think it's a big problem for the industry because, well, I mean, if you just look at data from FDA inspections, year after year after year, companies are at least, from the FDA perspective, still have a problem with how they manage CAPA and what are they doing. Do they have good processes? And that sort of thing. So, it's clear to me that whatever message the regulatory bodies are trying to communicate to medical device companies, for whatever reason, we, as an industry, are missing the message. And so, you know, I think there's a lot of reasons for that. I think there's a lot of challenges that we're face with.

But, that was really the big motivation is, let's figure out why this continues to be a problem and let's so to speak, let's maybe do a bit of a CAPA investigation and try to get to the root case, so to speak, to really understanding why this is a problem.

Mike Drues: Well, I think that's a great place to start, Jon. And actually, one of my suggestions was to perhaps, retitle this column, Does Your CAPA Process Need A CAPA? I think that's an interesting question.

Jon Speer: Yeah, that's a good idea.

Mike Drues: So, let's now start to dig into the weeds, because I know the audience wants much more specific, actionable items that they can implement, based on our discussion. So, one of the comments that you make in your column is that there's a lack of cross-functionality.

Jon Speer: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Mike Drues: In other words, CAPA's most often a process owned by the quality folks in the organization. And I think you raise an interesting question, does it make sense for quality to unilaterally make decisions as to what does or does not become a CAPA.

Jon Speer: Yeah.

Mike Drues: What's been your experience on that, Jon, and what's your recommendation there?

Jon Speer: Yeah, it's interesting because I think that we all get so busy in the day to day activities, or the functions, or the roles that we serve in, in our businesses, that over the years, I think the owner of CAPA has been inherited or taken on by the quality department. And I think there's so much other things that businesses are doing, like launching new products or focusing on manufacturing of devices, and so on and so forth, that these CAPA issues that surface, they become kind of afterthoughts or extra work, so to speak, that get added to the pile. And I don't think there's complete buy-in within an organization about how important a CAPA is.

I think CAPAs don't ... CAPAs should be treated like a project. And with any project, I don't care what it is, you need to have the right people, resources functions, roles, responsibilities, to effectively define and complete that project. But companies don't do this. They just say CAPA is a quality problem, just like a lot of times they say product development is an engineering problem. And I think that that lack of cross-functionality creates a lot of issues because if left to a single functional group to make decisions about things, they may make decisions from their limited view or limited perspective of the world. And it may not be good for the overall business.

And that the purpose of a cross-functional team involved with making decisions about what is and is not a CAPA, and then once something is a CAPA, also have an [inaudible 00:06:09] cross-functional team in place to basically, implement any sort of corrective and preventive actions is important, because it's more holistic. It's keeping a balance in place and understanding the different parts and pieces of the business.

Mike Drues: Well, I agree with you, Jon. And actually, I think what you're saying about quality is something very similar to what I've said about regulatory many, many times. And that is, regulatory should not be thought of as in isolation. It needs to be integrated with R and D and manufacturing, and all of the other areas, just like quality, as well.

So, if we take that silo approach, whether we're talking quality or regulatory, or something else, I think that unfortunately, we're setting ourselves up for even more problems in the future.

Jon Speer: We are.

Mike Drues: So, one of the recommendations that you make is that companies form a management review board, and that it should meet on some frequent basis, perhaps even once a week. What's your rationale for making such a recommendation?

Jon Speer: Well, I think, and I'll come back and answer that question specifically, but I want to ... The way most companies think about their quality system is, they're so focused on the compliance piece, you know, are we meeting the regulations? And you've ... And I'll paraphrase something you said in the past. If you're just focused on compliance, that just makes you average. And, but I think so far, so many companies have just, they're focused on just that compliance piece, because you know, for whatever reason, that seems to be the driving force.

Mike Drues: In other words, the tick box on the form and [crosstalk 00:07:48].

Jon Speer: Yeah, yeah, exactly. You know, it's make sure that we address this FDA regulation, and this ISO requirement, and that sort of thing. You know, they're so focused on compliance and this ... You know, there's end of regulations and in ISO 1345 requirements, it talks about this thing called a management review. And I think the way so many companies have structured the business is that, they look at that management review as a check box activity that happens once a year. You know, the more progressive companies, maybe, do it a couple times a year. But it's a moment in time. And they're going through their check list, did we do this, did we do this, did we do this. And they're not really getting a lot of value out of their quality system.

And folks, if you just have a quality system in place to check a box on the form, you've missed the point. And that's sort of really, gets out this concept of management review board that is cross-functional as, at least representational from quality and regulatory operations and engineering. And it might make sense to have it from a business development standpoint and an executive standpoint, and so on.

But it's cross-functional in nature, and it meets on a more frequent basis so that ... because things happens, you know, every day things happen in businesses. And you need a group that can make informed decisions about the necessary course of action. You know, does something need to be investigations in a more thorough fashion? Do you need to initiate some sort of CAPA?

So, that's really the idea, is a team that's there to represent all the necessary and applicable parts of the business, but to be able to dive in and make decisions on a more frequent basis.

Mike Drues: Well, once again, Jon, as your audience, I'm sure, appreciates, you and I are singing the same song, just in a slightly different key. I'm also a huge fan of having regular meetings via a management review board, or whatever you want to call it. I don't really care.

Although, to be honest with you, I don't like to be micro-managed. But when it comes to regulation, I in fact, don't want the regulation to say, "This group should meet once a year, or once a month, or once a week." I think that should be left to the discretion of the company.

Jon Speer: Mm-hmm (affirmative), for sure.

Mike Drues: For example, if you have a legacy device that's been on the market for, say, 20 years, and it's very well established, and everybody understands the technology. And it's a simple device, and you really don't have that many problems, there's no reason why people need to get together and talk about it, you know, on a monthly or certainly, a weekly basis.

On the other hand, if you have a newer product that uses very new technology, that's not well established, that does not have a track record of success and so on, then it obviously makes sense to meet much, much more frequently. So, my suggestion, and I made this suggestion to companies many times. And I'd love to hear your thoughts on it, is in our quality system somewhere, we, as an individual company, define our criteria as to how often this board meets based on our particular devices that are on the market. In other words, whether it's once a year, whether it's twice a year, whether it's quarterly, monthly, weekly, what have you, I want the company to be able to make that decision. And I also don't want it to be absolute.

I also would suggest some sort of a provision or a caveat in there that if, in the process of, you know, gaining more real world data from our device, that we start to see more problems, more complaints, especially if something is, you know, leads to a question of safety or efficacy, then we would have an immediate meeting, or an extra meeting, or a more frequent meeting. So, I want those criteria to be spelled out in the quality system, to be able to do what makes sense.

What are your thoughts on that? Would that be giving companies too much latitude? Too much flexibility? Do we really need to micro manage them and say, you know, you need to have this meeting every X number of days? What are your thoughts, Jon?

Jon Speer: Yeah, I can see both sides. I mean, I can see that it's really more appropriate to base that when this group convenes, based on the needs of the business. I get that. Part of the other thought is, if you get into the behavior on a more routine basis, and again, weekly, folks, you have to own your business. When I say own your business, you have to know what makes sense for what you're doing and what the needs are. You know, and you'll know. But as Mike's suggesting, based on your products and how your products are performing, and the issues that are happening. You'll get into a rhythm. You know, and I think getting into some sort of rhythm is important. And if that rhythm is weekly, if it's monthly, if it's quarterly, the point is less about the frequency, and more about the activity. And more about actually owning and understanding how important this type of group is to keeping your business, or getting your business to be a well-oiled machine, that instead of reacting to each situation and issues, that you're actually staying ahead of things.

You're being more proactive in nature. And that's really the essence behind this concept of an MRB, is being more proactive.

Mike Drues: And I agree. And just one small warning; Maybe not such a small warning for our audience, is that Jon and I are speaking now, purely from a quality or regulatory perspective. And one of the recommendations that Jon makes in this section is the importance of documentation and notes and so on. But, just be aware from a product liability perspective, that can be very problematic.

Jon Speer: Yeah.

Mike Drues: And perhaps, Jon, this might be a topic of a of a different discussion in the future and that is how do we cover our butts from a regulatory or quality perspective while at the same time not overly exposing our butts from a product liability perspective. There's a very, very fine line there. Okay, so let's move onto the next point that you make in your column and again, something that I agree with strongly and that is the tendency of many in our industry to be, to be reactive as opposed to being proactive and many of the corrective, sorry, many of the CAPA efforts focus on the CA part of the equation and much less so on the PA sort of the equation. As a matter of fact, I've said at FDA many, many times. We as an industry have gotten very good at the corrective action.But not So good at the preventative action because many of these problems seem to happen over and over and I've even gone so far as to say that maybe CAPA is the wrong acronym. Maybe The acronym that we should be using is PACA preventative action corrective action.

so what are your thoughts on being more proactive, Jon, in especially in circumstances where once we are aware of a problem then it's kind of easy to sell to the organization. Hey, we need to invest some time and resources to correct it. But what about when you don't know of a problem yet? Maybe your devices just getting onto the market maybe or device is still under development and even on the market and you're trying to think of anticipated problems and ways to prevent them. How do we convince our employers, Jon, to invest time and resources into solving problems that, that quite frankly don't exist yet?

Jon Speer: This is a big one Maybe one of the more challenging parts from a CAPA perspective that your organization may struggle with. And in fact I did a, I recently did a Webinar on a CAPA and the questions that came in that was the most common question is how do I get my executive team to understand the benefit of being more proactive instead of reactive? And I think there's a lot of, I think this is a bit of a self fulfilling prophecy that has manifested over time. Perhaps you're right, perhaps if we called up PACA instead of CAPA, the self fulfilling prophecy would've been that companies will be more focused on the preventive side or the proactive side. And I think another thing is for those who have ever been through an FDA inspection, it almost always originates through evaluation of your complaints, which complaints by their nature are almost always reactive types of situations.

Complaint handling

The event has already happened by the time you, you document and learn about a complaint. And I don't know if those are things that have sort of propagated this reactive focus or not, but I guess the opportunity here is really to try to shift that mindset. People ask, well, should I or should my ratio of corrective actions be compared to my preventive actions is there a magic ratio. No, there's not. There's not a magic ratio. I suspect that most companies, it's probably 9:1 corrective versus preventative, maybe even higher than that. But

Mike Drues: I'd like to see it the other way around,

Jon Speer: I would like to see at the other way around for sure, and I think that businesses need to understand that dealing with complaints, it's not fun. It's not a good business practice, but it is something of course that we need to do. But what if, what if we could develop a product that didn't have complaints? I mean, is that too utopian of a way of thinking to consider that we may not have a complaint or an issue with a product that we develop. I mean, from an engineering perspective, I mean that's sort of my objective, right? I'm trying to seek perfection I realize that that might not be attainable but what can I do from a product development standpoint, is there more that I can do from a due diligence to understand the problems or the challenges of the procedures that, that my product will be a part of or the other products that might already be in the marketplace.

If I spent more time understanding sort of the underlying issues that are involved. Then I think during I can incorporate that into the design of my product to try to mitigate and reduce the likelihood that there's going to be situations and events that happened and then it's, I know it sounds a little bit altruistic Mike, but it's really about really shifting that mindset. It's about paying attention to what's happening with your products and evaluating data and information that you're learning about those products and going out and soliciting that kind of feedback rather than just sitting back and waiting for something to happen.

Mike Drues: Well, Jon, whether the goal of no complaints or adverse events or anything else utopian or not, that's an interesting question, but I definitely think it's where we should be setting the bar. I think we as an industry can and should it set the bar much higher? We might not achieve it. But Simply put, if we set the bar higher, we will achieve more than if we set the bar as unfortunately we often do so low that we just about trip going over it, but I want to focus on the particular challenge that I mentioned. It's one thing when have a device on the market and there's some problems. There are some complaints coming in those cases it's usually a no brainer. You have to deal with them, but what we're talking about is the preventative actions oftentimes in my world, being involved with devices that are not even on the market yet, and we have and we've talked about Jon, all kinds of regulatory requirements for testing, including usability and so on.

But what we're talking about here is how do we address problems that do not yet exist and you gave some, some good recommendations. Let me add one more to the, to the mix, and this is something that your audience can consider whether it's an appropriate method in your own particular company. I'll leave that to each person, but a lot of people tell me that they fear the FDA and I say, no, no, no, no. You should not fear the FDA. You should have a healthy respect for the FDA, but you should not fear them.

Your biggest fear should not be what happens when FDA comes in to do a manufacturing inspection or something. Who should you fear? I mentioned them earlier, Jon, you should fear the product liability attorneys because they can do a heck of a lot more damage to a company than the FDA ever could. And as I may have mentioned in some of our previous discussions, Jon, a growing part of my business is acting as an expert witness in medical device, product liability cases. So perhaps some people in your audience you might, you suggest to your company, Gee! we need to do a better job of anticipating problems, not just because it's required by FDA dadada, but also to cover our what's in the future in terms of product liability something to think about

Jon Speer: and i think, i just want one quick thought on that too our industry practice has been to rely very heavily on information that's contained on product labeling and instructions for use. And I recall this was probably in a podcast discussion that you and I have had before that Mike Drews doesn't read instructions and I think others should. Yeah, I think we as, as a device developers and manufacturers, we need to keep that in mind. Our products should be fairly intuitive to the end user. We should assume that they're not going to read that instruction for use.and I think that's probably our approach has been so focused on, well I'll just put it in the IFU or I'll just put it on the label and we haven't really addressed the issue.

Mike Drues: Well, thank you for remembering that Jon, because as I sometimes say facetiously but also seriously as a PHD in engineering, if I have to read the instructions before using a product, some engineer has not done their job. Anyway, back to CAPA another of the issues that you bring up, and I've talked about this many times as well, is are CAPAs used too frequently or not frequently enough. In other words, I had a discussion not long ago with a friend of mine who's the senior VP of regulatory and quality for a fortune 50 medical device companies that is very large company. I won't mention which one, but he and I were okay. Best friend since graduate school and we were at dinner in California, had a discussion of what's the ideal number of CAPAs that a company should be having ? Is zero CAPAs our goal? Well, perhaps that means that our products are perfect.

Or perhaps it means that our CAPA system is not working. On the other hand, if we have tones and tones of CAPAs, we run into the possibility of the boy who cried wolf. so many CAPAs you get this sort of dilution effect. Kind of like when you walked through a crowded shopping mall parking lot and there's a car alarm going off. Nobody really pays attention because it happens so frequently. So what are your recommendations to our audience, Jon, on how to decide what should be or alternatively should not be a CAPA

Jon Speer: There's a bit of art to this, I suppose I look at a CAPA should be to address a systemic issue or a systemic opportunity. And I've seen so many companies kind of work at either extreme. The one extreme is where everything becomes a CAPA.You get a complaint, oh, it's a CAPA or you get a non conformance open it's a CAPA and if that's your practice, then that's probably over burdening your company, your resources through that. And now you got too many CAPAs as open and you're, all the other issues that we've talked about so far are going to rear their ugly head even more so because now you've got too many things to try to focus on and deal with and reserve CAPA for those, those big deals those. And don't wait for the things to happen.

And I'll use an example like maybe you find out that a certain type of fitting is not functioning the way that you thought and while that issue maybe systemic because it's happened multiple times and you're dealing with that from more of a corrective standpoint, use that as an opportunity to evaluate in a more proactive way or a more preventive way. Is that fitting use on other products in your portfolio or is something that type of connection point, is that something that's used at other points throughout your products and your processes and use that as an opportunity to be broadened the investigation to be more comprehensive in nature. So I guess like I said, the bottom line is use CAPA to address systemic issues that you're aware of or to try to prevent those issues from becoming big, big gotchas. Big, big problems.

Mike Drues: I think that's excellent advice for our audience, Jon. And I'll add one more suggestion to consider. And that is as we all know, both here in the US as well as in most places in the world, our quality system requirements dictate that we have a CAPA process. But one of the things that I see missing or woefully inadequate in most quality systems that I look at in medical device companies that I work with is that they do not have criteria in place to determine what problems, whether it's simply an observation on a manufacturing floor or complaints from the field or whatever, what problems will create a CAPA and what will not.

As a matter of fact, one of my recent companies that I'm working with right now, they put that decision in the hands of the customer service person who's taking the phone call complaints and they're the person who decide which gets passed on for investigation by engineering or which do not. And let me tell you, this is not a criticism of people that are manning the phones, but that makes me very nervous.

Jon Speer: as i say how's that working out?

Mike Drues: well, it's one of the reasons why they're having some problems unfortunately. But anyway, the point is I think I personally even as a regulatory consultant, I do not look to the regulation to solve my problems. I want the flexibility, just like we talked about before, to define those criteria based on my devices, my technology and so on. I don't think it's reasonable to have universal criteria because on one hand you might have a device company that's making this simple handheld surgical instruments like scalpels, or hemostats, or something. On the other hand you might have, other companies that are making totally implantable artificial hearts.

It doesn't make sense to impose the same criteria on both, I want that criteria to be established by the company. I'll also still a metaphor from the design controls, Jon, something that you and I are both familiar with and that is let your outputs become your inputs. These criteria should not be static on some base, a periodic basis, whether it's once a year, twice a year or more frequently than that. We take a look at the information that we're getting from the field, the real world data, so to speak, and we feed that back into our CAPA criteria. In other words, are there criteria that we have to add or modify in order to make this a living document? A risk management file.

A risk management file is not supposed to be a static document, not something that you create once and stick it in a file and never touch it again. That defeats the whole purpose. What are your thoughts on establishing criteria and specifically giving companies the ... not just the ability but the responsibility for establishing that criteria themselves?

Jon Speer: Well, that's important and I think we're so costumed to treating symptoms. We can look at this and our entire culture is certainly here in the West. Pick on health care for a minute, if you think about your healthcare, it's all about treating a symptom. If you drill down into the way we manage our quality systems, and day to day business activities and medical device companies including getting into campus, we're just treating symptoms.

Mike Drues: That's a good point Jon, and that brings us to our last point in your call and that is root cause determination. You make a very interesting statement and regrettably I agree with you 110%, and that is we don't spend a lot of time and actually determining what the real root cause is. I hear lots of people, especially engineers at conferences and other places, they talk about root cause and so on, but oftentimes they're just skating around on the surface, they're just simply applying bandage.

At least in my opinion, Jon, the root cause if many, if not most problems is actually between people's ears. It's the thinking that ... Einstein said, "The problems that exist in the world today cannot be solved by the same level of the thinking that created them." We have to change our thinking. What are your thoughts about root cause determination, Jon, and how can we do it better?

Jon Speer: Well, the practice, the most common practice that I've seen is that there's an issue statement or some description of the problem that we're trying to address. Most commonly what I see people do when it comes to defining root cause is basically a wordsmithing exercise. Whether rewording the issue or the problem statement and calling that the root cause and tell them is that the case. We have to appreciate it-

Mike Drues: Our patients are good at that area.

Jon Speer: Yes they are and if we do that, then we're going to be almost by de facto forced into just addressing symptoms. Something may manifest in one way, but unless we truly understand how that thing even happened to begin with, the likelihood of us taking necessary action to prevent this from happening again is as a snowballs chance, it's probably not going to happen, it's probably going to rear outside the head.

We have to apply some ... I'll say methodology and there's lots of tools out there that are designed if applied properly to help you with a root cause determination. They are plenty and I'm not promoting or advocating one over another. I do happen to like this tool called the 5 Whys. For those of us who have ever been around a three year old, I think we can almost immediately understand the premise behind the 5 Whys.

It goes like this, imagine a three year old ask you to go somewhere and you respond with your response, no or yes or whatever, and then you get another question. Then what's that next question? Has that three year old asks you why? Why? This continues over and over again? Well, it's that same mentality as far as how the 5 Whys operates. You take that problem statement and you ask why did this happen? And, then you ask another, why don't you describe that? Then you ask why? And, you ask why? You keep doing this until you get to an actionable root cause.

Whatever your methodology or your approach, my advice for you to determine that root cause is to apply some methodologies, some activity to drill down to try to get to something that's truly actionable.

Mike Drues: Well, it's interesting you used the metaphor of the three year old grandson because my grandson just celebrated his two year birthday just last month. It's one of many reasons why I take the approach to regulatory and quality that I do. One of my most important jobs is a regulatory consultant, is to ask questions, including questions that many people don't want to ask. If your audience can appreciate, does not always make me the most popular person in the room, but it is a job somebody has to do because if somebody doesn't do it in your room, I guarantee the FDA will do it.

Let's wrap this up because I know we've been talking a lot about gap and it's a topic that you and I feel strongly about and we have a lot of experience with and perhaps we can continue it at a different time. If you were to boil all of this down, Jon, what do you think would be the most important takeaway or perhaps two most important takeaways that our audience should come away with a based on our discussion today?

Jon Speer: First and foremost folks, I'm not a betting man that I'd be willing to bet a decent sum of money, and keep in mind I haven't even seen what it is that you're doing, but I bet your CAPA processes is busted, I bet it's a bet it's broken.

Mike Drues: Do we need a CAPA for your CAPA?

Jon Speer: Do you need? You probably do. If you're not getting, if you're dealing with the same issues over and over again, that's a symptom that your CAPA process is broken. If you're focusing on correcting and reacting to situations more so than you are being proactive, then your CAPA system is broken. If you leave the decisions about what is and is not, CAPA to a singular function such as quality, that's a symptom that your CAPA process is broken.

I would encourage people to really think long and hard about your CAPA process, and maybe as a good preventive action whether you believe it is good or not. Every year, why don't you issue yourself a CAPA on your CAPA process and prevent this from becoming a systemic issue for your organization.

Mike Drues: Well, that's good advice, Jon. I'll just add a couple of things very quickly myself. Another thing that I see missing in many almost all quality systems is, on some periodic basis to take a holistic approach. In other words, we often look at these CAPAs in isolation, but coming back to what we talked about a moment ago in terms of the root cause, oftentimes the root cause is much deeper than that, and the same root cause problem may have led to multiple CAPAs.

What I suggest to organizations is on some regular basis, again, whether it's yearly or twice a year, what have you? Take a look at all of your CAPAs and all of your complaints in the aggregate and basically trying to see the forest through the trees. In other words, look for similarities, where similarities don't seem to exist. This is not a skill that everybody has, but it is a skill that you can develop in yourself, I really believe that.

One of the first steps to doing so is the conscious awareness of it. That's takeaway on recommendation one, the two takeaways that I would share is very simple. Don't think about this as a CAPA, think about it as a PACA. I think we need to be putting, as Jon and I both talked about more emphasis on the preventative side as opposed to the corrective side because basically the more prevention, the less correction. That's take away number one and finally take away number two.

I'm not going to use my words, I'm going to use Einstein's. Einstein very smart guy, much smarter than me, Einstein said, "The problems that exist in the world today cannot be solved by the same level of thinking that created them." If we really want to do a better job, if we really want to solve these problems. We have to come up with not new regulation, at least not in my opinion, but new ways of thinking and looking at the world.

Jon Speer: That's a really good point. Guys Einstein also said that, "If you expect different results without change, that's the definition of insanity."

Mike Drues: There you go. Einstein was a very smart guy. They say, "If you're going to steal, you might as well steal from the best."

Jon Speer: I agree. Mike I want to thank you again for being part of today's discussion on the Global Medical Device Podcast. Folks, if you'd like to learn more about how Mike Drues can help you with your regulatory strategy, he's the best. I would encourage you to look him up, Mike Drues, DRUES and you can find him at Vascular Sciences, writes content for a number of industry publication. He's pretty easy to find and if you can't find him, reach out to me, I'd be happy to make a connection.

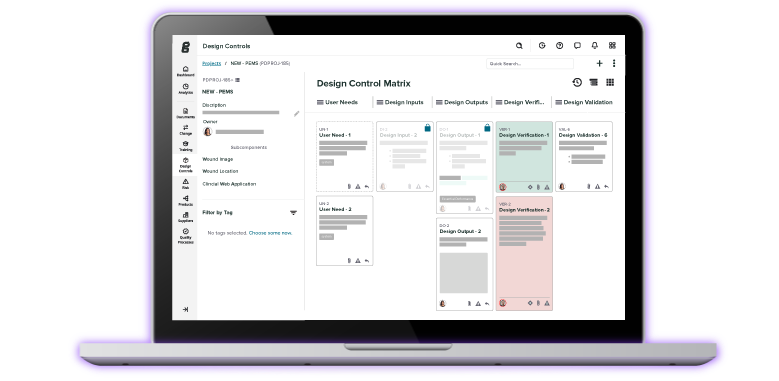

Lastly, as we wrap up this podcast today, I want to let y'all know our software has postmarket workflows designed for a number of quality processes including CAPA. If your CAPA process is something that you're serious about retooling, revisiting, reevaluating, I would encourage you to reach out to us at Greenlight Guru, just go to www.greenlight.guru and it'd be fairly obvious what to do. From there, you can click on a button to request a demo and we'd be thrilled to show you our QMS software platform. This has been Jon Speer, the host of the Global Medical Device Podcast and founder MVP of quality and regulatory at www.greenlight.guru.

ABOUT THE GLOBAL MEDICAL DEVICE PODCAST:

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Nick Tippmann is an experienced marketing professional lauded by colleagues, peers, and medical device professionals alike for his strategic contributions to Greenlight Guru from the time of the company’s inception. Previous to Greenlight Guru, he co-founded and led a media and event production company that was later...