Building Your Bill of Materials (BOM) to Accommodate Crossfunctional Needs

For many new medical device professionals a bill of materials (BOM) may feel like a big black box. Who owns it? How does it function within a QMS? How is it used differently in design versus in manufacturing?

In this episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast, Jon Speer and Etienne Nichols learn the answers to these common questions, and more, about a medical device bill of materials from guest Mark Rutkiewicz, VP of Quality at Innovize, Founder of Consiliso LLC, and author of Medical Device Company In A Box.

Mark has more than 30 years of experience in the medical device industry and takes organizations to the next level of quality system, product development, and operational excellence. His vision, experience, and hands-on leadership drive best practices in quality system processes and project management.

Watch the Video:

LISTEN NOW:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some highlights of this episode include:

-

The FDA and ISO quality system requirements include design controls, which have a direct correlation to BOMs.

-

The Design History File (DHF), Device Master Record (DMR), and Device History Record (DHR) are parts associated with design controls. Mark explains the difference between the three to build a product.

-

For BOMs, there needs to be one source of the truth and everything else needs to match it. A master document needs to be defined, then other files and records copy and configure the same data.

-

Based on configuration management, BOMs should include several components, such as a unique identifier/part number, description of part, quantity, unit of measure, operations step, assemblies, and reference designators.

-

When building a BOM, define attributes or metadata that accommodate manufacturing and design points of view to avoid confusion.

-

Design a flexible system. If you design for flexibility, then you’ll never have to worry about changing your quality system because it can’t handle a new product.

-

Determine the rules of interchangeability. As products change, remember to change the part number and update the version on the BOM.

-

Who owns the BOM? The medical device manufacturer owns the BOM because they are the approver and own the DMR and DHF.

Links:

FDA - Quality System (QS) Regulation

ISO - Quality Management Systems Requirement

Medical Device Company In A Box: The Case For Consiliso

The Greenlight Guru True Quality Virtual Summit

MedTech True Quality Stories Podcast

Greenlight Guru YouTube Channel

Memorable quotes from mark rutkiewicz:

“The Bill of Materials, you can also grow it to be a Bill of Documents and a Bill of Operations. All that is sort of what’s required to build a product.”

“That’s why there’s multiple documents today. The manufacturing people want to see it this way. The design people want to see it this way. They’re not talking to each other.”

“If you design for flexibility, then you’re never going to have to worry about, ‘Oh, I ‘ve got to change my quality system because I got this new product because my quality system can’t handle it.’”

“Every digit in the part number means something.”

Transcription

Announcer: Welcome to the Global Medical Device podcast, where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Jon Speer: Hello and welcome to the Global Medical Device podcast. This is your host and founder at Greenlight Guru, Jon Speer. Joining me is co- host, Etienne Nichols. Etienne, how are you doing today?

Etienne Nichols: Hey Jon, doing good. Good to be back.

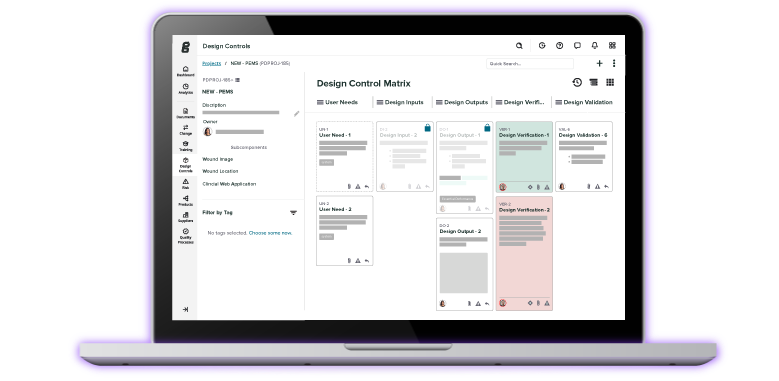

Jon Speer: Well, I'm glad to have you back. As the Greenlight Guru software platform has evolved, we are constantly listening to our customers to determine what new features or functionality should we incorporate into the software platform and we're soon going to be rolling out some functionality that's going to help you better manage bill of material, so I'm pretty excited about that. I know you've had a chance to see that a little bit, right?

Etienne Nichols: Yeah. It's going to be pretty cool. Revision your bill of materials and so forth, I won't give too much away. But, yeah.

Jon Speer: Yeah. And it ties into the design control, and I think this is one of those things where a lot of folks may not understand but there's a direct correlation. I don't want to get too ahead of ourselves, maybe I should just introduce our guest and then we can dive into it. Joining us is a repeat guest, Mark Rutkiewicz with Innovize and Consiliso. And Mark, welcome back, and I feel like every time I'm saying your name, I'm getting a little bit better at pronouncing it. So thanks for bearing with me.

Mark Rutkiewicz: Well thanks, Jon. Thanks for having me again. Etienne, nice seeing you again.

Jon Speer: Bill of materials, and maybe this is a good place to start. I think a lot of people don't, especially newbies to med device, don't necessarily understand what a bill of material is, what it is not and I would say they don't understand the correlation or the relationship between a bill of material and the DMR and the design control. Maybe that's a good place to paint the picture for folks.

Mark Rutkiewicz: That's what I was going to start with too.

Jon Speer: Good, dive in.

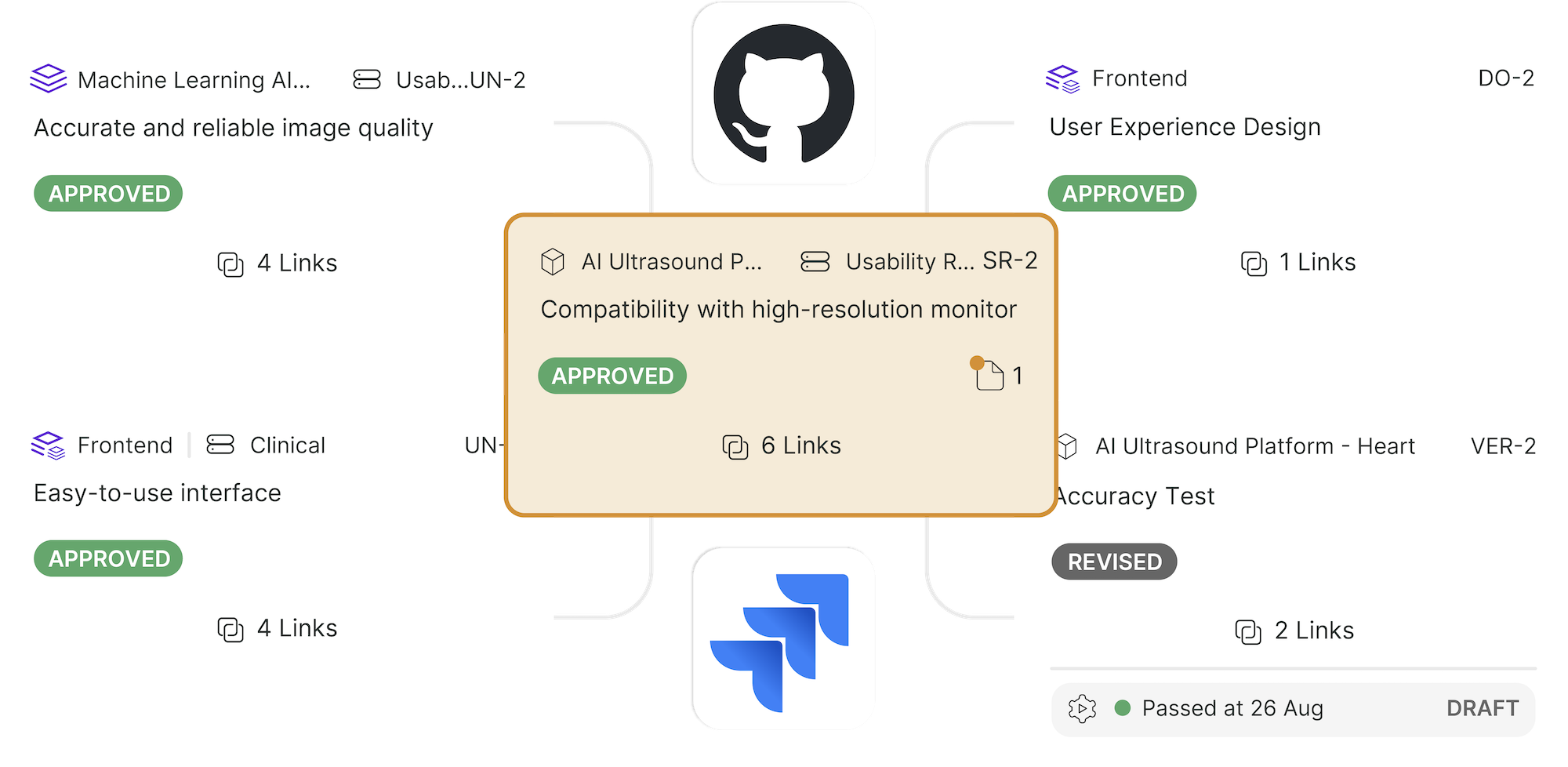

Mark Rutkiewicz: The quality system. The quality system requirements, both in ISO and FDA, they've added design control, which is great because it's the front end. As you look at design controls, there are design inputs, design outputs, design verification, design validation. Design output, that is what is your design going to be? And so that's the design output. Now everything that's developed out of design controls is part of what's called the design history file. Your design history file is everything associated with design. Now, part of the regulation talks about the device master record, all the information required to build the product. Well, the DMR is actually an output, is a design output. The DMR is actually part of your design history file. You can debate this with auditors, it doesn't really matter, as long as you have them, you need to have them and they need to be controlled. Your design output, device master record is everything you need to build the product. What do you need to build the product? Well, all the parts in the product need to be listed and defined and controlled. Now, device master record also though includes the instructions to build the product, who are your suppliers for those components, and then what operational steps to manufacture that. The bill of materials, you can also grow it to be a bill of documents and a bill of operations. All that is what's required to build a product. Simply saying, let's just start with a BOM because that's the easiest one to recognize. It's like, if you know you have, I have a catheter, I have tubing, I have a handle. Those are two parts, those are parts that will be on your bill of material. There's packaging material, so there's a pouch that it goes into, there's a label that goes on it, there's an IFU and it goes in a box. Those are six components that will on your bill of material. Now, what's interesting is what the design people, the designers come up with, they're using CAD tools to build this out and so we're using CAD tools. The CAD tool itself, you have to create what's called a PRT, a. prt file for each part. That just describes each physical part and so in the CAD, they can 3D and then connect them all together. And then when they put multiple parts together on a CAD drawing, they get what's called. asm file, which is the assembly of all the parts. Now you have two parts. If you look in the CAD software, the assembly has linked to it, all the parts, which the software automatically can print it out onto a design drawing. That's your bill of materials. Great, I got a bill of materials. Well, that's good for the designer, but how do you manufacture it? The designers don't put in the manufacturing process steps in there so you got manufacturing steps. I've talked about this a lot as Consiliso and consulting with companies. It's like, so that bill of material, I ask," How many bills of materials do you have in your company for this product?" As I start asking questions, it's typically seven, eight. You have the design document has the bill of materials on it. Well it's in the CAD and then you create a design document, so there's two locations for your BOM. And then, oh, because it's part of your DMR, you create a DMR document so your BOM is on your DMR document and your manufacturing work instruction defines, I got to assemble this, I got to assemble this component, this component, this component. Your bill of materials define your manufacturing work instruction. Well, I need a DHR record, device history record, evidence that I built it per the DMR. You may create a separate form that's your traveler document that has a bill of material on it. Now you got five documents that if you change, oh, and then you got to buy the part so you load it in your ERP system. And then if you have a quality system tool, like you guys might have a BOM or a PLM system or something like that, PDM system, the BOM is there. Which one is right?

Jon Speer: We hope they're the same.

Mark Rutkiewicz: Well, they all ought to be the same.

Jon Speer: That's a nightmare, that's a recipe for disaster.

Etienne Nichols: You just gave me a headache.

Mark Rutkiewicz: I go into any medical device company that I haven't touched and it's like, yeah, they all say all the same things. Like, yeah, why does an ETO take 30 days to process?

Jon Speer: That's part of the reason why.

Mark Rutkiewicz: The signature processes and that kind of stuff isn't done right beginning the front end, but the back end is like, well, documentation takes a week to process it because they have to make sure all the other documents are all changed at the same time. It's like, okay, one source for the truth, here's the BOM and this is what it's going to be and everything else has to match it. If you have an electronic BOM that has also a bill of documents and the bill of operations, then you've got it all in one spot. One of the things I've done for a lot of companies around your bill of materials, here's my materials, then you're on the bill of materials as you put a list of this is the manufacturing work instruction document. Here is all the tooling that's unique for that product, is on the bill of material too. And then depending on what product you're making too, your ERP system might have a traveler, might have a standardized one. Innovize actually, since we're a contract manufacturer, we're infinitely flexible there because every product is different and so we actually list, here are all the different operational steps that it goes through. And each one is different because we make 2, 000 different products for 200 different customers so it has to be that flexible. When I was under contract, while I was doing implantable heart occluders, we basically got three, three manufacturing travelers. We just put an identifier saying, this is routing A, routing B, and routing C on the BOM, so when the documentation group got the ECO to release, they would know how to load it into the ERP system correctly. And that was just showing our controls because our workflows were really simple in manufacturing there because it was basically the same parts you were making.

Etienne Nichols: I'm familiar with that.

Mark Rutkiewicz: Sorry, Jon.

Jon Speer: No, no, sorry. Keep going, man. Keep going.

Etienne Nichols: The situation you described, I'm familiar with that, multiple BOMs. And so the solution you're suggesting is having that one source of truth and then the others point back to it or eliminate those? What are you-?

Mark Rutkiewicz: Right. The biggest thing in the company is you define which one is the master. Now that's a bad word these days. I say it's like, which one? Well, the master is this but then everything else has to copy it. So the CAD drawing can do this, this is released here but then the master is, and it really want to probably have an electronic. So then if the master's electronic, then you can extract it. And if it's an XML format, then it can be configured to look like a traveler, it can be geared to look like a design document, it can be configured and it's the same data. So it's just applying different style sheet to the data, so it'll look what, the way you want it for the different users.

Jon Speer: It's almost like the prime, we'll use my wife is in real estate. And so they've changed the new term is now the primary. So the primary is the source of truth, it's where the metadata is. And it's almost like if the contract manufacturer needs elements of the bill of material or the design file or the EC, it's like pulling from that same data source. Right?

Mark Rutkiewicz: Right, yeah. One source.

Etienne Nichols: Right, one source.

Mark Rutkiewicz: So then when you change it, you change the source then everybody else has, if anybody has an issue, they know where to go versus like," Well, my document says this"," Well, your document's wrong. This is the one that's right".

Jon Speer: I've seen that problem so many times, especially when you have a relationship either with some supplier. It could be a contract manufacturer, it could be a part supplier, maybe you're getting an injection molded component. Like who owns the PRT and who owns the CAD, who owns the design and even with that, how do you know that the part you're getting is built to the right version of that particular component and it can be a nightmare.

Mark Rutkiewicz: Right, yeah. So yeah, in the past, a lot of companies use PLM systems to help manage it. But if you don't have a PLM system, a lot of companies use document management systems. Pharmas totally, document management. It's like, it's a process, but med device is devices so BOMs make more sense. Now, one of the other things about a BOM, if you can add additional metadata to the BOM. So when you look at a bill of material of wherever format it's, whichever it's the paper, whatever. Now each component on it should have a unique identifier, so ID part numbers, what everybody does. And actually this is based all on configuration management training, there's Configuration Management Institute that does training on this. I took that training, I knew this. I was a drafter back in high school so I understood the BOM concept back then. But with training and configuration management, I was like, oh yes, okay, now it'll make sense. I always did it this way but now I understand why because they went through excruciating detail on how to do it. But the bill of material, here's the part number, here's the description of the part and here's the quantity and the unit of measure. That is the key of a bill material. Now, you add a fine number up front. So if you have a drawing, you put the number 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and then you have a circle or balloon with a number on it and then it points to, this is one, this is two, this is three so that you can tell which ones are which. Great. So the part number creates a unique identification, the fine number helps organize it. Now typically most software systems use the fine number and filter there, if there's no fine number, it'll sort it by the part number. Now, if you have electronics circuit boards on a circuit board, your components also are capacitors and resistors and integrated circuits. There's standardized methodology for naming those, R1, R2, R3, C1, C2, C, so then you add another column on your bill material. That's your reference designators for electronic components, you usually don't need that for mechanical components. Now what most companies don't have, and I've always tell companies to add another column called your operational step. So what operational step in your manufacturing process is that component used? Now, if everything's on a one manufacturing step, it's all out OP10. So something's simple, you really don't need it. But if you have, it goes through multiple steps, here it goes through machining, and here it goes through cleaning, and here it goes through packaging, OP10, OP20, OP30. Manufacturing wants the BOM to be organized the way they're going to use it, which is different than the way the design people. So if you have a table and fine number is where the design engineers want it, the OP step is how the manufacturers want to see it. And then when you add in tooling and manufacturing work instructions, you could say, and the OP step with that document or forms can be linked to it. So then they can sort the BOM by the OP step and that's how they want to use it and the design engineer sorts it by here. And they don't look at anything below items one through a hundred or fine numbers or what they use, and they don't care about anything below it. And then that information is then used to load the ERP systems.

Jon Speer: That's really interesting. I guess I really hadn't thought about it from that perspective before, because to your point, as a design engineer, when I think of bill of material, I'm almost thinking about it from the outside in, I guess I'm oversimplifying here. But from a manufacturing standpoint, they're going to look at it almost from the inside out, and they're going to look at what are all the different sub- assemblies and how do these different sub- assemblies need to be snapped together and that sort of thing. So I think that's a good tip to folks, is however you build your bill of material, make sure you have attributes or metadata define such that and accommodate the points of view from a design perspective or points of view from a manufacturing perspective because if you don't speak that language it's going to create some confusion.

Mark Rutkiewicz: That's why there's multiple documents today. Most companies have them because the manufacturing people want to see it this way, design people want to see it this way and they're not talking to each other. And then you get into the concepts of design people, it's like, here, I designed this. Okay, so here when I was at cardiac pacemaker, with finding implantable pacemaker and stuff, and it's what kind of hierarchy do you have in your building material? Where do you create a subassembly? Do I have one level? Here's the pacemaker and here's all the components in the pacemaker. No, because this is the finished good pace and then if I sterilize it, it's a level below that, so you create another level. Oh, then the packaging level before it's sterilized, I want to give it another part number. And then I got the canned assembly, and then I got the hybrid assembly, and then I have the computer chip assembly. So it's a six to seven level deep build material, it's where your sub-assembly is done. The sub- assembly calls it another sub- assembly and so that's actually, they designed it so it matches manufacturing more. Well, when I was at company doing extra defibrillators, they blew it out this way. It's like, wait, you can't build it that way. So the designer built it, laid it out in this CAD drawing. It's like, no. So we ended up creating part numbers in between, but using the same design drawing because they had it on one picture. It's Like, no, we're going to do this as two manufacturing jobs and do them differently, but using the same design drawing. So that's where that comes in and really helps understand things. So if you do a bill of material, you really understand from the manufacturing. Now, if you're doing simple parts, it's all one. And then the other concept on a bill of material that I just want to most tell everybody here is, so you got one assembly and you have parts and you have one drawing. If you have a raw material, a single part, this is really simple. I got one part, the part number and the document number. So a lot of people make them the same thing, it's like, well, yeah, you can, but you really should have a part number and a document number, two different things because you want to be consistent across your whole company. One part has one drawing. Well, if you have a tabulated drawing, I have tubing and I'm buying this tubing from the supplier and I have five and six and seven and seven, eight in long length, I'm going to create dash numbers for each length because I want to create one drawing. I don't want to create seven different drawings and just only difference is it's length. I'll tabulate it, draw it once and say the length is variable. So I have one drawing, multiple parts. Printed circuit boards are just the opposite, I got one part, you need more than one drawing to describe a circuit board. What's the electrical schematic? What's the board layout? What's the whole drawings on it? What's the mechanical layout? You can have four, what's the test requirement? I've had seven, eight documents that describe one part.

Jon Speer: Amazing. How many layers are in your board? It makes them even more complicated. So...

Mark Rutkiewicz: Yeah. So you need to design a system that's flexible. It's like, well, but mine's really simple. Okay, then for your company you might want to just do it that way but if you design it for flexibility, then you're never going to have to worry about, well, I got to change my quality system because I got this new product because my system can't handle it.

Jon Speer: Well, I think a lot of, on the thinking about how you're going to architect your system and I know, having spoken to you many times in the past and reading your book on Consiliso, this is really the premise behind that, is you've got to be thoughtful about how you're architecting the system. Don't just drop things in place and cross your fingers and hope that it works forever. It takes a little bit of thought.

Mark Rutkiewicz: Right, yeah. And so I've been in the industry 35 years and I've seen all kinds of startups to multinationals, being on an acquisition, being the other of acquisition, disposable parts to capital systems. And it's like, what I put in Consiliso is the concepts and a lot of it's tied to concepts of configuration management, concepts of lean, the concepts of system engineering are all what's in there. It's all this best practices, I put it down, all my experiences in med device, this is the best way of doing it. And one other thing then with a bill of material, when do you change a part number? It's like, oh, I'm not going to change a part number. It's the same thing. As things change, you need to determine rules of interchangeability. In previous podcasts, we talked about the UDI and there's rules of interchangeability, there's rules of interchangeability in your assembly. And the basic question here is if you change the product, could you put them in the same bin in inventory? You don't care, when your shipping guy picks it up, does he care which one he pulls out? If he doesn't care, then they're interchangeable. It's like, no, no, no, no, that can only go there and this can only go there. Well then they have to have two different part numbers, they can't have the same part number anymore. You change your part numbering so that he can't pull the wrong part to ship to a customer. So rules of interchangeability and your part numbering on your BOMs is really important.

Jon Speer: This is an area that lot of companies get tripped up because versioning or, it's like, well you have version and how do you plan the obsolescence and all these sorts of things. But I like the way you simplified that description, like if the distinction does not matter, then it is same part number. If the distinction is a difference that is important, then they're separate so I get that. That's a really simple way to think about it.

Mark Rutkiewicz: Yeah. And there's a lot of schemes, in my book I actually talk about it. There's three ways of doing part numbering too. When most med device, and most people say is you do a semi smart number, you have a base number and you use dash numbers so that these are associated with it, so that's really good. I've done it where you have pure sequential numbering, everything just gets a new number. There's no dashes, just everything gets a new number. It works really well, trying to find things that are related is tougher. Then you get to the other end, every digit in the part number means something.

Jon Speer: And then you're going to run out of digits.

Mark Rutkiewicz: It will break down. Marketing can use that for the model number, great. But don't use it for your part numbering, it's going to fail. No matter, you can't design that. Use a semi smart numbering.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, smart numbers get dumb pretty fast. Yeah. Yeah, that's it. Well, I think Jon mentioned the revising or the versioning of the part. What about alternate parts within a BOM?

Mark Rutkiewicz: Yeah, absolutely. So, there's different ways of doing alternate parts, depending on what kind of part it is. You could have, let's just say, I was doing electrical components on a circuit board, even in the military, way in the day, before I got in the med device even. We had a spec number, a part number for this component, it was a transistor and it's like, it has to do this, this and that. So the spec is generic and then you can have multiple suppliers and here's their part so I can buy this from multiple parts' suppliers for that part. Same part number, not alternate primary, because I used to say I can buy the same part from multiple manufacturers. Alternate primary, their parts are different, their specs are slightly different between the two. So you get two different part numbers. You can put them on the bill of material, like I mentioned before, you want to give them same fine number, because they're located in the same spot in the design drawing and the same quantity. Then you add another column in your bill of material, alternate, primary, subcontract actually. I actually put three, I've done it with three attributes. So everything default says primary, you have one, but if you put an alternate, then you control it in the quality system as your alternate primary. Now the EERP system only wants one number, ERP systems don't like alternate primaries at all. So you can say, this is what it is and we've loaded it this way. Now if the buyer says, I can't buy that part, okay, according to the quality system, I can use the alternate and they can look in the system, say, oh, I can swap it and then you change the EERP system for that job, whatever and use the alternate part because it's allowed over here. So that's how you want to be able to do that. And then sometimes subcontractors, I want them to make the part, I'm going to give them part of it and they're going to return part of the backend and so it's subcontracted build. That's typically dealing with alternate primaries on the bill of material. So you define it up front and has to be approved through the ECO process.

Etienne Nichols: That makes sense. That find column, I think is invaluable as well as, like you mentioned the primary secondary. That's great, very cool. So we talked about contract manufacturing in a previous episode as well. So the BOM, it seems obvious I guess, but really nothing's obvious. Who owns the BOM in these different scenarios.

Jon Speer: That's a good question.

Mark Rutkiewicz: The device manufacturer owns the BOM. You own the DMR, you're telling the contract manufacturer to bill it for the DMR. Now the contract manufacturer can give you lots and lots of help, but you're responsible for it. Startups come here, it's like, I need a drawing. It's like, okay, we can make it for you as a service, you own it, what number do you want? And I don't know, they have to sign it, they're the only approver, is the medicalized manufacturer is the approver of the document. This is your document that we're going to build to because you signed it. You don't have a quality system yet, you need to have one. And then it's like, well, what number did I give it? Well, call it this. So the part number is, wound care dressing. It's like, okay, that's not a number, but you don't have any other way of assigning it so you're doing it that way, that's fine. But the device manufacturer owns the BOM because they own the DMR and they own design history file.

Jon Speer: Let me ask a follow up to that, who owns the suppliers?

Mark Rutkiewicz: Oh... Well, your quality system needs to define-

Jon Speer: I like the reaction.

Mark Rutkiewicz: Your quality system needs to define who your suppliers are. Device master record should define on your bill of material, who is the supplier for each of those parts. Like I talked about in alternate primaries. Some systems, some PLM systems, you have the supplier of the part and you have the part number and you link in on an electronic ECO, you link in which manufacturer's part number from which manufacturer is approved for that part. And if it's one to one, then it's only one, but that is all part of your device master record. And it's tied to the BOM, but it's really part of the whole thing and some tools out there have that all linked in there. I'm not sure if your new ones are going to have that or not, but that's what you want to do. Because that's really, if you have it all in one tool, then you can run a report and do, like I said, you can have multiple views of your BOM. You could run a BOM explode report, okay, BOM will explode into a document.

Jon Speer: The B- O- M- B

Mark Rutkiewicz: And it basically goes down to the multiple levels because you have, here's all the components, here's all the parts, here's the quantity and here's the supplier. That's actually your device master record, so there's the listing to device master record. And that can be actually in some tools, it's set by the effective date. So what did this DMR look like? You can say every second of every day, as different parts change, you can tell what the DMR is at that point in time.

Jon Speer: Yeah. Again, at the end, I think we're finding that whenever we have Mark on the Global Medical Device podcast, we could talk for a long, long time on each one of these topics. This might be a good point again, to put a pin in this topic. Let me hopefully say the right thing and summarize. A bill of material, I've used this as a analogy or metaphor, whatever the right assembly, whatever the right English construct is. But the way I think of a bill of material is, it's a list of ingredients and by itself, eh, it's not super intelligent. It doesn't necessarily tell you what order to put those ingredients together, per se. And this is where the contents of your DMR are more like the recipe that talk about when to use this ingredient and that ingredient that to combine them. Do you think that's a probably overly simplistic, but do you think that's a good way to think about that?

Mark Rutkiewicz: That's a really good way. That's a really good way. Yeah. And it's like, I'm making chocolate chip cookies, oh, I'm going to swap butterscotch chips. Well, it's no longer chocolate chip cookies, it's not interchangeable. It's butterscotch.

Jon Speer: Butterscotchies. Well on that, now that I'm now thinking about food, let's call this one a wrap. Mark Rutkiewicz with Innovize and Consiliso. Mark, this has been a great time, I'm glad we've had an opportunity to continue conversations with you on a variety of topics and hopefully we'll find other opportunities to chat again real soon. But thank you so much.

Mark Rutkiewicz: Sure. Thank you for having me.

Jon Speer: Yeah, absolutely. Etienne, I know you're having a good time so we're getting on a rhythm here. So of course, thank you as well for cohosting.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, absolutely.

Jon Speer: And folks again, I'm sure you've heard me if you've listened to the Global Medical Device podcast, which since we're number one, I'm guessing you've listened to an episode a time or two. And if this is your first time, welcome but, really like Guru, we're here to help you. We have a medical device success platform, a software solution that helps you manage many details of your live as a medical device professional. And, and now we have, I'll assume we'll have functionality on helping you better connect the dots between your design history file, your DMR and your bill of materials, so pretty exciting. If you'd like to see those features of functionality and how they all tie together, well, just reach out to us. Go to www.greenlight.guru and click a button that says you'd like to learn more, you'd like to have a call, you'd like to have a conversation and we'd love to have that conversation with you. We'd love to understand what your needs and requirements are and see if we have solutions that can help you better manage your bill of material and connect that information to your design control and your design history file and be able to convey that information to your manufacturers, so check it out. As always, thank you for listening and until next time, this is your host and founder at Greenlight Guru, Jon Speer and you have been listening to the Global Medical Device podcast.

ABOUT THE GLOBAL MEDICAL DEVICE PODCAST:

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Nick Tippmann is an experienced marketing professional lauded by colleagues, peers, and medical device professionals alike for his strategic contributions to Greenlight Guru from the time of the company’s inception. Previous to Greenlight Guru, he co-founded and led a media and event production company that was later...