Using the Bucket Method for Medical Device Risk Management

.png?width=4800&name=podcast_standard%20(2).png)

Risk management: It’s a topic that needs to be navigated carefully by medical device companies.

It’s been gaining a lot of traction in the industry, because some recent standards have focused on risk management.

Today’s guest has seen companies take their risk management plan directly from their design controls and paste them into their regulatory submission forms. This is not a correct way to approach risk management, because it gives an incomplete picture.

Mike Drues, the president of Vascular Sciences, has been a frequent guest on our show. Not only do we listen to him, but the FDA and Health Canada do, too, because Mike works with these regulatory agencies in addition to working with medical device companies.

Today we’re talking about risk management. Mike has a three (plus one bonus) bucket approach to dealing with this important topic.

Listen Now:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some highlights of this episode include:

- Mike’s systematic approach to risk management: three “buckets” he uses when developing his plans.

- How to measure, track and present the probability of harm of not using the device.

- Mike’s thoughts on using FMEA as a tool.

- The problem with equating misuse as off-label use, and what the difference is.

- Mike’s solution for facing the problem of liability pertaining to off-label use of a device.

- Why it’s important not to become a slave to whatever tool(s) your company is using when dealing with risk management.

Links:

Memorable quotes by Mike Drues:

“I use the same process whether I’m bringing a band-aid onto the market or a totally implantable artificial heart.”

“I’m not against using FMEA... but we have to recognize its limitations.”

“It’s a weak argument to say that misuse is the same as off-label use, especially if it’s the standard of care.”

Transcription:

Announcer: Welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast, where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Jon Speer: Oh, yes, risk management. Definitely, one of those topics that's gonna be front and center for those of us in the medical device industry for quite some time, maybe forever. So, enjoy this episode as I talk to Mike Drues, once again, on the Global Medical Device Podcast, and our topic is all about risk management.

Jon Speer: Hello, and welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast. Once again, this is your host Jon Speer, the VP of Quality and Regulatory and founder at Greenlight.guru. Also, I have with me, Mike Drues. Mike is the president of Vascular Sciences. You've heard his insights and wisdom before. Guess what? FDA listens to Mike as well, as does Health Canada and other regulatory bodies and medical device companies all over the world. Mike, thanks for joining us this morning.

Mike Drues: Thank you, Jon. My pleasure to be with you and your audience as well.

Jon Speer: Alright. Do you have your sleeves rolled up?

Mike Drues: I definitely do.

Jon Speer: Well, today we're gonna dive into... I'm sure we've talked and danced around this topic a bit before, and I'm sure this won't be the last time, but the topic is risk management. And we're gonna dive into some... I guess, some interesting novel approaches. I'm gonna dive into something that you've been advising and using in your world as a way to help companies navigate this topic. I'm gonna talk a little bit about a few things that I've seen and experienced. But risk management, are you up for the challenge?

Mike Drues: I'm definitely up for it, Jon.

Jon Speer: Alright. Well, let me just give a brief, I guess, prelude, so to speak, to our audience this morning. Risk management is one of those topics that I think is gaining a lot of traction in the med device industry and has been for the past several years. That was really kinda... I guess, a high watermark so to speak, with the emergence of ISO 13485:2016. And that standard when that was revised a few months back, has put a lot more emphasis on risk management and risk-based approaches and risk-based QMS, and focuses in those methodologies that are described, processes that are described in ISO 14971. So, I know companies struggle with this. Mike, I know you've experienced that, so any horror stories you wanna share before we dive into some details today?

Mike Drues: Well, thanks, Jon. The little prelude that I would offer is that I often see companies take their risk management plan from their design controls and literally copy and paste that into their risk mitigation strategy for their regulatory submission, for their 510(k) or PMA or what have you. And without even looking at it, I, right away, I know that it's wrong or at the very least is incomplete. Because as we'll discuss, the risk in a design control sense is only... Is very limited, it's only one small slice of the pie compared to other aspects of risk that, in my opinion, are critical to go into a regulatory submission.

Jon Speer: Yeah...

Mike Drues: So, one...

Jon Speer: No, go ahead.

Mike Drues: I just gonna say, one small piece of advice, and again, we'll get into the details here, is please don't just, as often people do, copy and paste any risk management plan from the design controls into your risk mitigation strategy for your regulatory submission because it's just not adequate.

Jon Speer: Yeah. And a lot of people get really confused on this topic. FDA, I guess explicitly in the regulations, doesn't really say too much about risk management.

Mike Drues: They don't. And the question is, as we've talked about before, Jon, is that a good thing or a bad thing? I would like to believe that that would be up to us. As professionals, engineers, or scientists or designers or regulatory professionals working in the medical device industry, we would know how to handle that and we would not need the FDA or anybody else to micromanage us in that regard. But that's just my view and that's honestly not the view of everybody in this industry.

Jon Speer: Well, and I think... I go back to early on in my career, and I remember one of the first times that I got involved with risk management, and at the time, we were using an FMEA approach. [chuckle] And I think we did just... It was really a checkbox activity, to be quite honest, it was very late in the project, it wasn't done in the spirit of adding value to what we were doing. But the belief at that time was that we needed to have risk management. So, I remember barricading myself at my computer and my desk for about three hours, putting together this FMEA document all by myself and I got to check the risk management box on our designer view form and that really defeated the purpose.

Mike Drues: I strongly agree, Jon. And I personally believe that using any of these standardized or traditional approaches to risk, whether it's the FMEA or the different ISO approaches that you mentioned a moment ago, those are at best-limited approaches to risk. And so if you'd like, I'd be happy to quickly talk you and your audience through my more systematic approach and then we can discuss the merits of applying it.

Jon Speer: Yeah. I'm intrigued that you shared with me an article and I'll be sure to put a link to that in the transcript that's included with this post, the link to your article, and I'm gonna call it "Mike's Bucket Approach to Risk Management." So why don't you tell us a little bit about this, it's intriguing.

Mike Drues: Sure. So, I'm happy to. So, the idea came from years of experience. And I've been playing this game for nearly 25 years now, and seeing people do exactly what you've just described. And that is; they'll follow one of these standard methods, or they'll get a bunch of engineers together in a room and have sort of a risk brainstorming session, where they just sort of randomly pick off as many different risks that they possibly can. This is what I call the cherry-picking approach. It's not a very organized, it's not a very systematic approach, and as a result, you can never be assured that you got all of the important risks that you need to cover.

Mike Drues: So, over the last several years, I've developed a more standardized, a more logical approach. Which, by the way, FDA has just recently announced that they're gonna be adopting in part, as to their approach to risk in the future. But here's the idea. I break my types of risks into three buckets. For those in your audience who remember the old Bozo Circus show, this is like the grand prize game approach.

Jon Speer: That was the best part.

Jon Speer: So bucket number...

Jon Speer: The best part of the show, Mike. [chuckle]

Mike Drues: That's right. So bucket number one is what I call the probability of direct harm. The probability of direct harm. Now, this is the most obvious form of risk. This is the one that most everybody thinks of. And this is the only form of risk that is addressed in the design control sense of the word. So, the probability of direct harm means, what is the probability, what is the likelihood that harm will be caused to the patient? Usually it's to the patient, occasionally to the caregiver, as a direct result, as a direct consequence of using your particular medical device. So that's bucket number one. The probability of direct harm.

Jon Speer: Okay.

Mike Drues: Bucket number two; is the probability of harm if we do not use our device. One of the many interesting regulatory differences between a 510(k) and a PMA, is that in a PMA submission, as some of your audience probably knows, there is a regulatory requirement in the submission to consider what FDA calls alternative practices and procedures. What I call the probability of harm of not using. We're using different words, but we mean exactly the same thing. So if we don't use our device, what other devices could we use? What other surgical procedures are available? What drugs are available? And so on, and so on. So, that's the probability of harm if we don't use our device. That's bucket number two. And, again, that is not addressed in the design control.

Mike Drues: And the third bucket, is what I call the probability of harm by providing the wrong information. The probability of harm by providing the wrong information. This is endemic in all diagnostic products. For example, telemetry, like EKG monitors. Imaging, like CT or MR. In-vitro diagnostics, and IVD for cancer detection. I use that as a quick example. Let's say we have an IVD for, say cervical cancer. What is the probability of telling the patient that they do not have cancer, when in fact they do? That would be a false negative. Or alternatively, what's the probability of telling the patient they have cancer, when in fact they don't? That would be a false positive. So, that's the probability of harm of providing the wrong information. And once again, that is not considered in the design control sense of the word of risk.

Mike Drues: Now, those are my three buckets of risk. And we can go into those in more detail, if you want. But one other bucket, a bonus bucket, if you will.

Jon Speer: This is the grand prize.

Mike Drues: Is what I call... That's right. Is what I call regulatory risk. Now, regulatory risk also has many connotations, but regulatory risk means what is the probability that I am not successful in selling whatever it is that I'm trying to sell at the FDA. When I go to the FDA and I'm down there at least once a month. I'm gonna be down there the end of this week, doing a pre-sub meeting for a company. Every single submission to the FDA has a regulatory risk associated with it. We cannot eliminate it. We can minimize it, but we can't eliminate it. So when I work with companies, I always discuss with them. I never discuss this with the FDA, and I always discuss with them, what is the regulatory risk of that particular strategy? But I just stir that in for sort of completeness. The first three buckets are the most important. The probability of direct harm, the probability of harm if we do not use our device, and the probability of providing the wrong information. Jon, I know you have a lot of experience in risk, and especially in the more traditional approaches to design to risk and the design controls, and so on, and so on. What do you think of my Bozo Circus approach to it?

Jon Speer: Well, we probably need to remove the clown reference when we talk about risk. But as far as the bucket methodology, [chuckle] I do like that a lot. And I think, I'm speculating here, that most of those listening are probably most familiar with bucket number one, the probability of direct harm. This is where, as you mentioned, this is the context in the design control, design and development aspects, where we're identifying and evaluating risks associated with the use of the device. I think buckets two and three, and then, the bonus bucket of four... And let me recap for everyone. Bucket number one, again, it's probability of direct harm. Bucket number two is probability of harm of not using. Bucket three, probability of providing the wrong information. And bonus, bucket number four, is assessing the regulatory risks associated with your product.

Jon Speer: I think, when you think about direct harm, and we'll dive into that here in a few moments, get into more specifics, but I think that's an area that, for the most part, I think we all, as medical device product developers and manufacturers, I think we do an okay job of wrapping our head around that, and I'll explore that here in a moment with you. But I'm curious about the probability of harm of not using and the probability of providing the wrong information. Engineers, technical people, they're often looking for some sort of guide or prescriptive tool or methodology to use. Is there some other advice or guidance that you can provide the listeners as to how to capture that? Is this a report? Is this a spreadsheet? And I know I'm getting down into the very tactical, down in the weed level, but what are your thoughts?

Mike Drues: That's a great question, Jon, because we wanna make this as pragmatic for our audience as possible. And obviously, if anybody has specific questions about how to apply these buckets to their own individual devices, please feel free to contact us, we'd be more than happy to talk to you. But in a general sense, let's talk about bucket number two and number three. Starting out with bucket number two, the probability of harm if we do not use it.

Mike Drues: So I mentioned a moment ago, that this is one of the many differences between a 510(k) and a PMA. In the PMA, there is a regulatory requirement, what FDA calls "alternative practices and procedures", what I call "the probability of harm of not using." Once again, we're using different words but we're saying exactly the same thing. That requirement does not exist into 510(k) universe, at least not yet. We have had in the interest of full disclosure, your audience probably knows that I work as a consultant for the FDA as well, we have had some discussions about adding that requirement into the 510(k), and for that matter, the de novo as well. I personally think there is some merit to doing that, but it's not in there yet.

Mike Drues: The question is, why is it in the PMA? The simple answer is, when you think about it, it makes sense. Because PMA products are by definition, higher risk products, oftentimes life-supporting or life-sustaining, and it's not sufficient to look at only the risks associated directly with your particular device. You also have to look at the risks and how they compare to other devices, other surgical procedures, other drug options and so on. And if you really wanna get into the details, the PMA requirements says "alternative practices and procedures", but it doesn't say for example, which ones that we have to consider.

Mike Drues: So I'll give you a quick example. A couple of years ago, I was helping a company bring a type of catheter to the market that was being used for controlling blood pressure, and this was a PMA device. And so the PMA requirement required us to consider alternative practice and procedures, including drug options. There are more than 170 drugs on the market that have as part of their label, "antihypertensive". So does that mean that we have to compare our catheter to 170 drugs? Well if it did, this catheter would never come on to the market, nobody would ever do that. So what we had to do is we had to figure out a way to sell this, to minimize our regulatory risk with the FDA. And in a nutshell, here's how we did it. Not getting into a lot of pharmacology, but we can break those 170 drugs into three or four different categories.

Jon Speer: Okay.

Mike Drues: And what we did was we took the one or two market leaders in each of those three or four different categories and we compared our device to those. So instead of comparing our device to 170, we compared it to six or eight. That's a much more reasonable number. The question becomes, why is it six or eight? Well, that's the logic that I just outlined to defend it because what is much more important when we go to the FDA, what is much more important is where we draw the line. That's not really important at all, what's more important is our ability to defend it. We chose to compare our device to these six or eight different drugs and here is exactly why. It's the job of the FDA, in my opinion, to criticize everything. In other words, if the company comes into the FDA and says, "The sky is blue.", the FDA's job if they're doing their job, is to say, "Okay, prove it." And that's our job. So that's a quick example on the probability of harm of not using or alternative practices and procedures. Again, I know a lot of your audiences in the 510(k) world, you're probably not used to thinking in those terms yet, but I emphasize the word "yet". That might be a regulatory requirement in the future. And even if it is not, I think just as part of being a prudent professional, that's something that we should include anyway.

Jon Speer: Yeah, it makes really good sense. And I'm gonna jump into the FMEA spin here in a moment. But as you describe this bucket of "the harm of not using", I hear that there's a strong clinical aspect to this, would you agree?

Mike Drues: Yes. In that particular case, there was definitely a strong clinical aspect of it. But I suppose by definition, for both bucket number two, the probability of harm of not using, and for bucket number three, the probability of harm of providing the wrong information, there are gonna be very strong clinical aspects to both of them. Because again, think about the cancer example that I used a moment ago. What's the probability of telling the patient they do have cancer when in fact, they do not? And what's the probability of telling the patient they do not have cancer when in fact, they do? In my opinion, every regulatory strategy, whether it's a 510(k), a PMA, a de novo, what have you, every single one should address all of those buckets of risk.

Mike Drues: And by the way, one other approach that I have that differentiates my approach to so many others, is I'm not interested in just simply meeting the regulatory requirements. In other words, I wanna demonstrate to my friends on the FDA side of the table that I know what the heck that I'm doing, that I'm a responsible professional. And I use exactly the same process whether I'm bringing a Band-Aid on to the market or a totally implantable artificial heart. I use exactly the same process, and I apply the exact risk analysis that you and I are discussing here, whether it's a band-aid or an artificial heart.

Mike Drues: Now obviously, in the case of a band-aid, some of these things would not be applicable and I would probably say that the probability of providing the wrong information is not applicable to a Band-Aid, because we're not providing any information. But nonetheless, I still include it in there because I wanna make it painfully obvious to my friends on the other side of the table, that I know what the heck that I'm doing.

Jon Speer: Right. I appreciate you going into some depth and detail on the buckets. That's very, very helpful. Now, I wanna take a slight turn, probably stay... We can stay on the context of the bucket approach to risk management, of course, but I wanna dive into this topic a little bit of FMEAs. And Mike, I probably I'm referred to in the industry these days as the anti-FMEA guy, when it comes to... I think I...

Mike Drues: But that's okay, Jon, because once upon a time the vast majority of people thought the earth was flat.

Jon Speer: You mean it's not? Well, anyway, this topic of FMEA is something that I think has been used and abused and overused way too often, and when it comes to medical device risk management. As people listen to you describe your buckets and specifically the harm of not using or the probability of providing wrong information, buckets two and three. I can imagine, some people, especially those FMEA die-hards were probably thinking, "Oh that's a use FMEA." And I have two issues with FMEA. So what are your thoughts about that as a tool?

Mike Drues: Well, I think that, philosophically, you and I are exactly on the same page, Jon. Let me be clear, I'm not against using the FMEA or any of the other tools that you and your audience are familiar with when it comes to risk. The only thing that I'm suggesting is that we have to recognize the limitations that they all have.

Jon Speer: Exactly.

Mike Drues: None of them are perfect. None of them do 100% of the job. And the concern that I have and perhaps you have this as well, is that when people go through using one of these standardized methods, even if the FDA "accepts it", even if some other regulatory agency accepts it, doesn't necessarily mean that it's complete, it doesn't necessarily mean that it's right, it doesn't necessarily mean that once you fill out that form that you're done. Because it's just not that simple. And getting into the use aspect, Jon, maybe one other issue that we can touch on briefly, 'cause I think your audience would be very interested in this, is this whole idea of on-label versus off-label use and misuse, and so on. Jon, I know you're a big design control person. So why don't you recap for the audience how the design controls treats misuse. What do they say about that?

Jon Speer: Well, when you go in to the design control process, you need to describe your intended use of your products. As far as that is concerned, that's how you label your product, that's how you market your product, and if you know about some likely misuse of your device, that's something that you should try to account for from a design perspective, and ensure that no cases where it's known where your product or technology will be used and into application that's different that what you intend, that's very much a gray area at times, but if you know that you should do something about it. And in some cases, some would even say in some extreme cases, that you might even need to design your device in a way that prevents that misuse that you do not intend.

Jon Speer: So it's a slippery slope, especially when companies start to go through the design control process and try to get a product cleared through a lesser indication, so to speak, knowing that the device is gonna be used for some different applications. The classic example from back in the day is stents. Almost every stent company in the world would bring a stent to market under a biliary indication, knowing full well that the stent was being used for vascular purposes. And that's a big no-no. If your risk and your design control activity is only focused on the biliary aspects, but you knew that it was gonna be used in vascular aspects, that's negligence. So that's something that you need to be aware of as product developers as you're going through the design control process.

Mike Drues: Well, that was a great response, Jon, and I'm sure that that helps your audience understand. It was, as you know, a loaded question, coming from me, because one of my biggest problems with the design controls, is that they essentially try to equate misuse and off-label use. In other words, a lot of people think that misuse and off-label use is the same thing. I don't see it that way at all.

Jon Speer: No, I don't either.

Mike Drues: I think there's a lot of very legitimate uses of products, not just devices but drugs as well that are off-label, but they are not misused. As a matter of fact, what we teach in medical school is not what is on the product's label, we teach the standard of care. And so I think it's a weak argument, and many people try to make this argument, but it's a very weak argument to say that misuse is the same as off-label especially if it's the standard of care. Again, this is another reason why I prefer my bucket approach as opposed to some of these other standardized tools because we don't play those games. And just one last thing that I'll share with your audience as we approach the end of our time together today. Like you, I spend a fair amount of my time going into companies and essentially helping them put together their risk mitigation strategy, or I should say, their risk management plan for their design controls.

Mike Drues: And typically the way that we do this, is we'll put a bunch of engineers in the room, and we'll have sort of a brain storming session. And that is, we'll tick off all of the risks associated with the on-label use of a product. And this happened to me once a few years ago. And then the topic of off-label use came up, and as soon as that happened, the senior person in the room who happened to be a senior VP of Regulatory, in a very large Fortune 100 medical technology company, he said, "This meeting is over. Don't let the door hit you on the you-know-what on the way out."

Jon Speer: Oh my goodness.

Mike Drues: Why do you think he said that?

Mike Drues: I'll give you a hint. It had nothing to do with regulatory. It had everything to do with product liability.

Jon Speer: Well, yeah. There's this fear at times when it comes to mismanagement that you're kinda screwed either way. Damned if you do, damned if you don't. If you don't document it and it comes up downstream, then shame on you. Or even worse, maybe if you do document it, especially things that are off-label uses of your product, that you went into this eyes wide open, and you almost project that this could happen. So I imagine that that person had a legal background, or a strong legal coaching in some way, shape or form, and thought that that might lead to some downstream litigation.

Mike Drues: Well, that's exactly right. And so just to help to make sure that your audience understands, and then I'm gonna offer you my pragmatic solution to that problem. And it's not a perfect one, but it's the best one I've been able to come up with. You'll tell me what you think. But you're exactly right. The reason why he ended the discussion is because of product liability. Long story short, and I'm not an attorney nor do I play one on TV, however, I have been involved in a number of expert witness cases, if the opposing counsel can show that you knew or should have known, or as my attorney friends like to say, were thinking about a particular risk, on or off-label, it doesn't matter, that you did not sufficiently mitigate, you actually are held to a higher level of responsibility, a higher level of liability than if you are not. I hate to say it, Jon, but when it comes to the American legal system, ignorance truly is bliss. And so, here is my solution. Again, I'm not proud of this solution, it's the best solution that I've been able to come up with, and I've asked many of my attorney friends for a better one. They have not been able to give me one.

Jon Speer: Alright.

Mike Drues: At the beginning of all of my risk management discussions, I will say, and nobody is to ever write this down, but I will say for the purposes of this discussion, let's limit our discussion to risks associated with the on-label use of our product. And again, I hope everybody appreciates why I would say nobody should ever write that down, because it doesn't take a JD after somebody's name from Harvard Law to have a field day with that if they find it in a meeting document. But unfortunately, we've created such a culture where not only have we not created incentives to encourage people to ask certain questions, we've actually created strong disincentives for people to ask certain questions.

Jon Speer: I know.

Mike Drues: And as an engineer myself, that bothers me, but that's the most pragmatic solution that I have come up with. Jon, do you have any thoughts on that?

Jon Speer: Well, I'd like to just kinda... I do, and I'd like to use this to wrap up our discussion on risk. Mike, before I do so, this was a fun topic. We're just skimming the surface. I'm sure we could talk two or three more sessions on this in future podcasts so I'm gonna invite you right now for us to do that downstream.

Mike Drues: Would be happy to, Jon.

Jon Speer: Alright. But I guess the sort of the final words, so to speak, not to go all Jerry Springer, but the final words on this... Two television references today, Bozo Show and the Jerry Springer show.

Mike Drues: From a long time ago, some of your audience probably doesn't even know who we're talking about.

Jon Speer: Look it up, I'm sure it's on YouTube. The topic of risk is an important topic, and as Mike just shared with us, one of the key concepts when you're engaged in risk management activities is, you need to really scope it out, and you need to make sure the rules of engagement, so to speak, in that scope definition is clear to those who are contributing to your risk management exercises. As Mike suggests, on the sketchy topic or the slippery topic of off-label use, if that's something that can come up, be sure that your team is aware of you're gonna focus on the on-label use, and make sure that that scope is clearly articulated within the context of your risk management efforts.

Jon Speer: One other thing I wanna leave the audience with is this, there are lots of tools that are available. We touched slightly on the FMEA tool, there are other tools like fault tree analysis, there's HAZOP, there's hazard analysis, and there's use case scenarios. And there's all sorts of different tools that one might use when it comes to capturing the risk management. The tool choice is... Honestly, it's a little less important, that where companies get into trouble when it comes to risk management, is when they put all of their eggs in one particular basket, such as FMEA. We're gonna just do an FMEA and that's all we're going to do. When companies do that, that becomes problematic. So be sure your approaches are holistic. And, Mike, that's why I like this bucket approach to risk management that you've offered. Those four buckets, or three buckets and the bonus again are; number one, probability of direct harm. This is the activity that you're doing during the design and development process. This is evaluating how your products are gonna be used and the potential harm that can result to patients.

Jon Speer: Bucket number two, the probability of harm of not using. Again in Mike's example he shared a case where they compared the technology to some current standard of care and made an assessment of the possible harm that could result of not using. And then the third bucket is the probability of providing the wrong information. Again, Mike provided a great example. If you provide the wrong information, what kind of ramifications could happen to a patient? So those three buckets, and then the fourth bonus bucket, the regulatory risk, assessing that. Notice that in each of these buckets there's no tool per se, it is a methodology, it's an approach, it's to ensure you've captured risk from a holistic point of view. So, Mike, any final words before we wrap up today's session?

Mike Drues: Well, thank you Jon for that wonderful synopsis of what we've just discussed. And the final thought that I would leave your audience is, Jon is used the metaphor here of a tool which I think is very appropriate, regardless of which tool that you use. And, as Jon mentioned, there are a number of tools in the risk management area that one can use and Greenlight offers some great ones as well, but none of them are perfect and they all have limitations. And we have to remember that just like a risk management tool, or any medical device for that matter, a tool is limited by the skill level of the user. So don't become a slave to your tool. On the contrary, make sure that your tool works for you. And regardless of which tool that you're using, ask yourself, or ask the people that you're getting this tool from, "How do these other aspects of risk, how are they taken into account," via that particular tool? And if they're not, then you need to figure out some way to get them in there and you need to talk to somebody. Jon and myself we would be more than happy to do that.

Jon Speer: Absolutely. Absolutely. Well, Mike, thanks again for joining the Global Medical Device Podcast. Ladies and gentleman, you can find Mike Drues, D-R-E-U-S, look him up on LinkedIn. He's the president of Vascular Sciences, he's advising regulatory bodies, he works with medical device companies, so he has some wonderful insights. He has his finger on the pulse of what's happening at FDA and other regulatory agencies throughout the world. So definitely look him up on your quest when you have questions about regulatory strategies and pre-submissions and the bucket approach to risk management. He'll be happy to help.

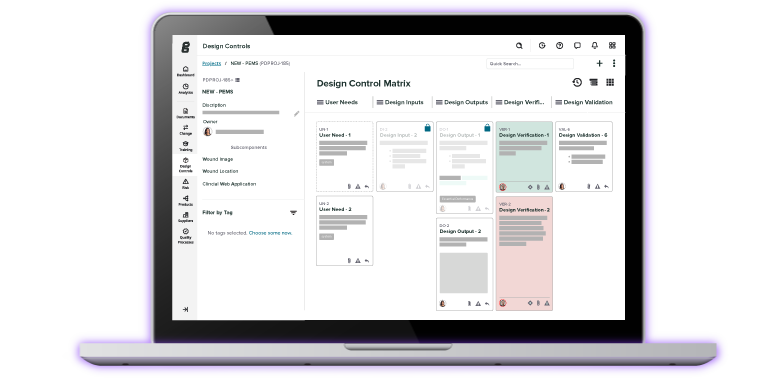

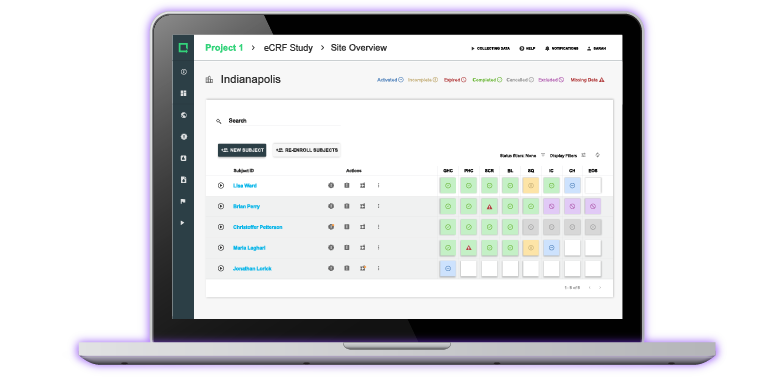

Jon Speer: Again, this is Jon Speer, the VP of Quality and Regulatory and founder at greenlight.guru. And as, Mike alluded to a moment ago, yes, greenlight.guru does have a software solution to help you manage ISO 14971 risk management. We also have a software solution to help you capture and manage and maintain your design controls and integrate those two things together. As well as a workflow for document management where you can manage, maintain, store your entire quality management system, all of your documents and records. So if you're interested in that and improving efficiency in your documentation and record-keeping practices as you bring new products to market, be sure to go to greenlight.guru, request a demo and we'll be happy to chat with you about that. So thanks again for listening to the Global Medical Device Podcast.

About The Global Medical Device Podcast:

![medical_device_podcast]()

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Nick Tippmann is an experienced marketing professional lauded by colleagues, peers, and medical device professionals alike for his strategic contributions to Greenlight Guru from the time of the company’s inception. Previous to Greenlight Guru, he co-founded and led a media and event production company that was later...