5 Tips for Medical Device Engineers on FDA Design Controls

.png?width=2400&name=5%20tips%20(1).png)

If you’re in the medical device industry, you may think that design controls are a confusing imposition on your process.

They’re a necessary part of your requirements as a medical device developer and we’ve noticed that this area tends to be rife with misconceptions, confusion and generally making things into a bigger deal than they really need to be. That’s right, design controls don’t need to be a confusing mess!

That being said, there are some areas that we’d like to address to help medical device engineers navigate their way more easily through design controls requirements. Let’s take a look:

#1. Don’t believe the misconceptions

Probably the biggest misconception about design controls is that they equal a heavy load of burdensome documentation. People who believe this also often believe statements like the following:

“Following good design controls will only slow down our product development."

"Design controls will stifle innovation in our business.”

Look, the thing is, if you believe these statements to be true, then your own design controls processes and practices are out of date and need to be overhauled. There is no need for design controls to be overly burdensome to medical device developers as there are simple ways of keeping yourself compliant.

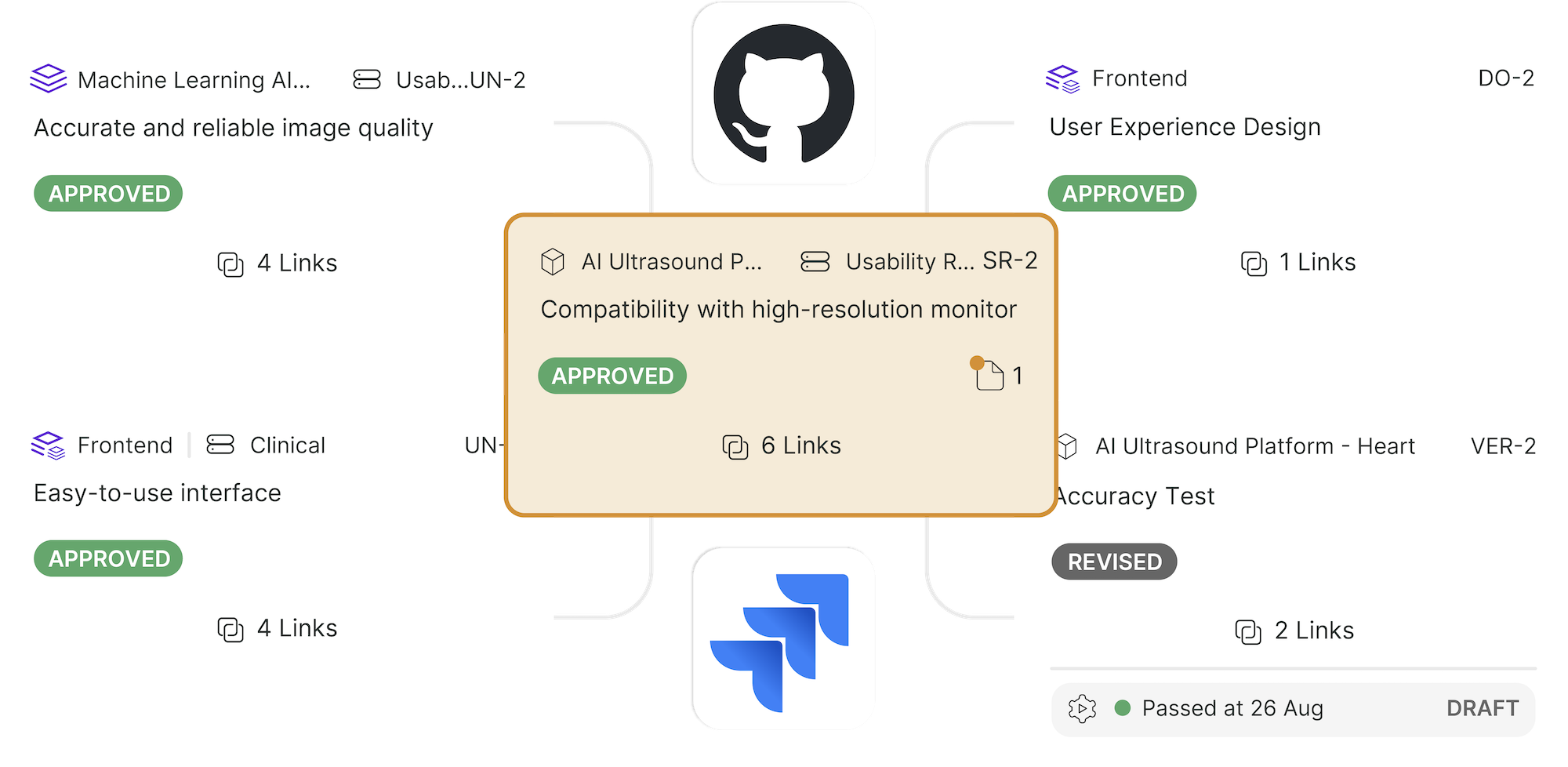

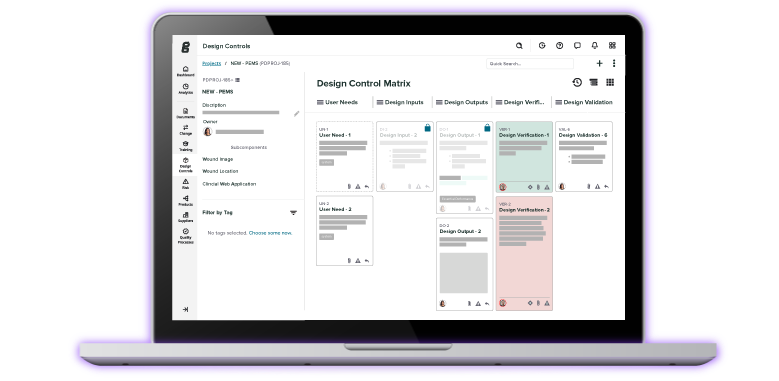

Design controls are essentially about demonstrating that your product is safe, effective, and meets its intended use. You could sum all of this up in an “intended use statement” and then use that statement as your pillar. You then have the basis to formulate your user needs, which feed directly into your design outputs. Coming full circle, you then have design validation that ensures that your product meets user needs.

In this way, design controls in fact aid product development and innovation. Your goal has to be to create a product that meets that specific “intended use statement” and is proven to be safe and effective. Design controls are the evidence to support your claims that this is so.

A robust design control practice aligns with regulations and allows you to be flexible and innovative. These controls shouldn’t be treated as an afterthought, but rather should align naturally throughout the design process.

#2. Keep your plan fluid

A huge mistake that we often see is that companies treat design controls as a chore to get out of the way. With regard to a design plan, this is often done at the beginning of a project then locked away. This fails to acknowledge that plans change, in fact, most companies will find themselves making a number of pivots.

Think about how a project is broken into phases, (without specifying preference for any particular methodology) there is a beginning, middle, and end. In the beginning, you’re in your discovery phase. You have ideas, perhaps crude prototypes, and an idea for intended use. You don’t know what you don’t know and as such, those things you discover become fuel for your design criteria.

Even keeping intended use as the pillar for your design ideas, you may go through various pivots throughout the middle phase(s) of product development. This is why your design & development plan should be dynamic, developed, and updated throughout each phase of the project. It is a living document, open to change.

It’s also worth clearing up another misconception; there’s often confusion about what a design & development plan actually is. The plan identifies the process that you will go through, resources required and design to be used. It is not just a project schedule. We often see the that companies are presenting a “plan”but it is in fact just a schedule, often in the format of a Gantt chart. This might be helpful in terms of keeping product development on track, but it is not the intent of a design plan. The design plan should describe what is actually happening rather than appear as a schedule.

#3. Recognize user needs vs. design inputs

Another concept to be aware of is the difference and relationship between user needs and design inputs. There is a great concept of the “user story”, which describes the things that the user will do with respect to the product, whether they be a medical professional, patient or someone who assists the patient. Think about what the user will do, how they will interact with the product and answer the question, what is important for them? The answers to these questions are what you need to capture as user needs.

A common practice is to describe these stories in vague ways, using terms like “better” or “easier to use”. This is an acceptable and important practice to embrace. And starting with somewhat vague statements as user needs is actually a good way to try to do so.

How does this relate to design inputs? User stories become the foundation for establishing design inputs. To state this another way, design inputs make the user stories more specific and measureable.

The inputs are quite simply the requirements for your device design. They must be objective and stated in such a way that can be demonstrated through testing or analysis. You can see where terms such as “better” simply do not cut it when it comes to design inputs.

We wrote more on defining user needs, including 8 questions you should ask here.

#4. Recognize design inputs vs. design outputs vs. design verification

People get confused as to what design outputs are. They want to capture through testing, items that prove inputs have been met and show these as design outputs. This is a complete mix-up of terminology.

Let’s break it down:

Design inputs - These define all the performance criteria, requirements, and features of your medical device product. As mentioned earlier, they should stem directly from user needs. Good design inputs provide the foundation for a strong and successful medical device.

Design outputs - We like to think of design outputs as a "recipe" for your medical device. Design outputs consist of all the parts, components, inspection procedures and other materials or procedures that go into your medical device. They are the documents you would give to someone who has the job of assembling your device.

Design verification - The goal of design verification is to prove design outputs meet design inputs. It is all of the testing, analysis, and inspections that serve as your proof to demonstrate your medical device has been designed correctly. As you can see from these definitions, people are often making the mistake of mixing up design outputs and verification. It might seem like semantics, but it’s important in terms of having your paperwork completed correctly.

#5. Start design controls early

Another relatively common action taken by medical device developers is thinking that they can afford to delay design controls until after a working prototype is established.

The idea is often: “Let’s stay in the research phase for as long as possible. When we’re sure we have a working prototype, we’ll document design controls.”

This is a mistake for a couple of reasons. Firstly, it’s not so easy to play “catch up” on design controls, there are often so many moving parts that something is bound to be forgotten. Secondly, you miss the entire point of keeping the design controls.

Through each iteration you are learning something and your design controls become an important record of learning. You might not nail your prototype the first or even the fourth time around, but you surely learnt something with each version. Capture this in documentation so you have a good record of it.

Final Thoughts

Design controls do not have to be the big, imposing task that they are often made out to be. In fact, setting them up the right way can encourage innovation and speedy product development rather than slowing it down.

Establish your design controls early, preferably with a centralized, electronic system that allows access to all who need to be involved. Staying on top of design controls right from prototyping will not only help to keep you compliant, but will help to enhance your learning experience over the course of development.

Jon Speer is a medical device expert with over 20 years of industry experience. Jon knows the best medical device companies in the world use quality as an accelerator. That's why he created Greenlight Guru to help companies move beyond compliance to True Quality.

Related Posts

The Ultimate Guide To Design Controls For Medical Device Companies

Why You Need To Stop Treating Risk Management & Design Controls as Checkbox Activities

How To Navigate the Difficult Road of Medical Device Product Development While Avoiding the Common Pitfalls

Get your free resource

7 Rules for Effective Design Controls