15 Habits of Highly Effective Regulatory Professionals

.png?width=4800&name=podcast_standard%20(2).png)

Quality and regulatory professionals in the medical device industry have to deal with a lot.

In this episode, Mike Drues of Vascular Sciences shares 15 of his highly effective habits and tips to help you lead your organization.

You have an opportunity and obligation to explain the current regulatory structure in the industry - embrace it, don’t resist it!

LISTEN NOW:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some highlights of this episode include:

- Poker Game: Relationship between a company and the FDA is like a poker game; even if someone understands the regulations, doesn’t mean they win

- Think Globally: Startups and new companies make the mistake of not considering international regulatory strategies; satisfy needs of various places

- Consider Regulatory from the Beginning: It’s never too early to think about regulatory in product development lifecycle; minimize burdens and problems

- Don’t Reinvent the Wheel: When it comes to clinical trials, data, and real-world evidence - can they be justified, even if the FDA asks for them?

- Competitive Regulatory Strategy: If you follow in somebody else’s footsteps, you’ll never go anywhere new

- Don’t Just Copy Others: Lots of sheep in medical device industry who take the path of least resistance; not aware of their options

- Know All of Your Options: Know about available options, as well as the advantages and disadvantages of each, to get your medical device on the market

- Don’t be Myopic About Risk: All conventional risk approaches are limiting; some aspects of risk are important to consider but not addressed in them

- New is Not Necessarily Your Friend: If you think you’re working on a newer, novel device, you’re probably not: Regulation? Guidance? Reimbursement?

- Use Label Expansions to Your Advantage: Tempting to bring a product with all the bells and whistles to market, but higher likelihood of being unsuccessful

- Design Your Label Like You Design Your Device: Spend time and money on label design; use all tools available to express your message

- No Submission Should Ever be Rejected: 75% of first-time 510(ks)s are rejected; minimize or eliminate rejections through advanced communication with agency

- Communicate Early and Often with FDA: It’s not the FDA’s job to tell you what to do; tell, don’t ask and lead, don’t follow

- Don’t Treat FDA or Other Regulatory Agency as Your Enemy: Don’t approach agency as beta tester or with minimum done to get it to sign-off on a product

- Don’t be the Regulatory Police: Don’t tell a company what they can’t do, but what they can do; don’t let regulation hold you back

Links:

7 Habits of Highly Effective People

Memorable episode quotes:

“Just because somebody understands the rules of poker, i.e. the regulations, does not necessarily mean that they are going to be a good poker player...and win the game.” - Mike Drues

“It’s never too early...to begin considering your regulatory.” Mike Drues

“Just because FDA asks you to do a clinical trial, doesn’t necessarily mean that you have to do it.” - Mike Drues

“I think people fall in love with wanting something to be new.” - Jon Speer

TRANSCRIPTION:

Announcer: Welcome to the Global Medical Device podcast where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some the world's medical device experts and companies.

Jon Speer: You know there are a lot of things thrown at us quality and regulatory professionals in the medical device industry all the time, and on this episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast, Mike Drues will share some of his habits of highly effective regulatory affairs professionals. So I hope you enjoy this episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast.

Jon Speer: Hello and welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast. This is your host the founder and VP of quality and regulatory at Greenlight Guru, Jon Speer. And today we are going to dive into something a little bit different. Hopefully something fun. I know our guest Mike Drues of Vascular Sciences is really anxious to share some of these tips. But we are going to dive into some highly effective habits and tips for regulatory professionals. So Mike are you ready to dive in?

Mike Drues: I'm ready Jon. This is patterned off of one of my favorite books, 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, by one of my favorite authors, Stephen Covey. And you know Jon, I always try to under promise and over deliver, so why stick with just seven. Why not double that and add one for good measure. Let's go through these top 15 habits for regulatory professionals.

Jon Speer: Yeah and the book by Stephen Covey is excellent folks, so if you haven't read it you should definitely give it a read. But, lets dive right in. So, I think I will start with number 15. This one is interesting. This is a poker game in every sense. What do you mean by that Mike?

Mike Drues: So Jon as I have talked about many times, I characterize the relationship between the company and the FDA as a poker game in every sense of the word. And just because somebody understands the rules of poker, i.e. the regulation, doesn't necessarily mean they are going to be a good poker player, and it certainly doesn't mean they are going to win the game. I want to do everything I can, legal of course, I don't want to be wearing any orange jumpsuits in order to win the game. So there is a heck of a lot more to this game than just reading and understanding the regulation.

Jon Speer: Alright, that's good tip. Number 14, think globally. I mean I can imagine what this means. Obviously we are, in the world we are in today it is more than the US. Expand a little bit on what you mean by think globally.

Mike Drues: That is exactly right Jon. A common mistake that I see a lot of early stage companies, especially small and start up companies with limited resources. They don't consider what I call international regulatory strategy early enough in the process. In other words, it's very common for a company to bring a device onto the market in one place and then move onto a second place, only to come to find that that second place wants a piece of information that the first place didn't want. So now they have to do additional testing and some cases additional clinical trial all over again in order to collect that additional information. Can you say ka-ching, ka-ching, ka-ching. It is a very common mistake and it is also a very rookie mistake. So my best advice, identify the first few places, maybe three or four places that you want to do business and pool their regulatory requirements so that all of the testing, bench top, animal, clinical, what have you, will be enough to satisfy the needs of all of those places at once.

Jon Speer: Yeah, I echo that one in a big way. A common practice is I will talk to a company that we are interested in the US market first and then maybe in a year or so we will go down the path of the EU. And that is fine if that is the strategy that you employ for launching your product. But do consider that downstream market. It might be something that's needed from the EU perspective that while you are going through this the first time, to get FDA clearance, it might be the right time as far as cost, budget, timeline, things of that nature. So do think globally. I can echo that one in a big way.

Jon Speer: Number 13 consider regulatory from the beginning. I mean, isn't it obvious?

Mike Drues: Well perhaps it's obvious to you and I, Jon, but it's not obvious to an awful lot of people. Because one of the most common questions I get from people is how early in my product development life cycle should I start considering regulatory. And of course my short answer is it's never too early even one nano second after you come up with the idea for the device is not too early to begin considering your regulatory.

Mike Drues: Now Jon, as a regulatory consultant myself, obviously that sounds self serving, but that's not really my intent here at all. The simple reality is there is so much that I can do to help a company, as they go through their product development processes, they design their device. After all my personal background before getting into regulatory, Jon, as you know, is in Biomedical engineering. So I speak engineer. There is a heck of a lot that I can do to help them as they design their device to minimize their regulatory burden later on. And also to avoid getting into problems later on. I suspect this is true on the quality side as well. You know so many times a company will call me up and say they are having a problem, they are in a hole. Can you help me get out of this hole. I'll say sure, I'll be happy to help you get out of this hole. But I also have to say that if you called me six months ago or 18 months ago maybe you wouldn't be in this hole to begin with. So bottom line, consider regulatory early, very, very early in the process. And also consider quality, very early in the process as well.

Jon Speer: Mike, that reminds me, we are covering the habits of highly effective regulatory professionals in this episode and I think maybe something we can do in a future episode is to cover the habits of highly effective quality professionals. I will make sure that considering quality from the beginning is definitely going to be on that list. From the regulatory perspective, it is really key because you have to know what that regulatory strategy is and to the point above about thinking globally. That really will guide and direct you as to the path that you need to follow to getting your product to the market. So starting it early is going to give you the most insights, keep your eyes open to what's ahead of you so you don't get several months into an endeavor only to find out some twist or turn that you didn't consider from a regulatory perspective. So I certainly echo that as well.

Jon Speer: Number 12, don't reinvent the wheel. What do you mean by this?

Mike Drues: So that is another great one, Jon. So this is in the general area of clinical trials, clinical data and real world evidence. Simply put, I see a lot of companies do clinical trials that quite frankly, are not justified. And just because FDA asks you to do a clinical trial, doesn't necessarily mean that you have to do it. So if you have a device already on the market and you are going back to the FDA for example for a label expansion, to add a new indication on your label. If you have data, what we call real world evidence or real world data, that supports that particular indication, even though it might not be in a randomized clinical trial, even though it probably is off label use. And in some cases even though that data may not have originated here in the United States, but perhaps somewhere else in the world, it may likely be possible for you to use some or all of that data as part of that label expansion here in the United States. So, bottom line Jon, and this applies not just to clinical data but to everything, FDA can ask you to do anything they want. Doesn't necessarily mean that you have to do it. So if you are going to collect additional clinical data, make sure that it is justified.

Mike Drues: Now one other thing that I want to say, I'm not looking for an excuse not to do a clinical trial because I don't want to spend the time or the money. That's not what I am talking about here. What I am talking about here is, if I have legitimate data that I can use, then why should I have to go out and collect new data, you know when I already have a pile of data already. So bottom line, don't reinvent the wheel if you don't have to.

Jon Speer: Good point. So item number 11 is competitive regulatory strategy. Talk a little bit about that.

Mike Drues: So this is another of my many favorite topics to talk about. So many companies, they will develop their regulatory strategy to get their product up to the market, by essentially following in someone else's footsteps. The problem with doing that Jon, is if you are following somebody else's footsteps, there is one thing that I can guarantee is that you will never go anywhere new. So if you are bringing a device onto the market, it maybe possible for you to develop your regulatory strategy to make it more difficult for your competition to follow in your footsteps as well. This is an idea I came up with a number of years ago, I coined a phrase competitive regulatory strategy, being able to make it more difficult for your competition to follow in your footsteps. There is a litany of different ways that it can be done. But that is the idea of competitive regulatory strategy.

Jon Speer: You and I have talked about that topic before. I almost liken it to what a lot of companies do from an IP or a patent perspective. A lot of companies will look at their patent portfolio in a competitive way for similar reasons and there is no reason why you cannot use your regulatory strategy in a similar way. So that is really good advice.

Jon Speer: Alright..

Mike Drues: Absolutely. It is a good metaphor, intellectual property is a good metaphor. Although to be fair, the protection on IPs is stronger than it is for than what I am suggesting here. But it is a good metaphor.

Jon Speer: Sure. Alright, so I have at number 10, don't just copy others.

Mike Drues: So again, I can't tell you Jon, how many times people come to me and, I'll share with you one case in particular. Somebody came to be and said were bringing our device onto the market in as in 510(k). I said Okay, sure, no problem, but out of curiosity, why are you doing it as a 510(k). Well did we have another option? It's amazing to me how many sheep we have in this industry Jon. I am trying to be kind here. Most people, of course I am generalizing, just simply want to follow in someone else's footsteps. They want to take the path of least resistance. There is nothing wrong with that, if it is to my advantage to do that, then I will be the first ones to do that. In fact I'll be put in 72 point font on my PowerPoint, when I walk into the FDA, I am doing nothing more than what the people did before me. End of discussion, don't let the door hit you on the you know what on your way out. But if it is not to my advantage, to follow in someone else's footsteps, or if it is not possible for me to do so, I will be the first to work with the FDA to carve out a new path.

Mike Drues: You know, as we talked about before, Jon, the 510(k) is the workhorse of the medical device industry here in the United States. But a lot of people think that the reason why the 510(k) is the most common choice, is because it is the best choice, or in some cases it is the only choice. And that is absolutely not the case. You know McDonald's is one of the most successful restaurants in the world. Is it because they make a good hamburger? Not so much. So just because virtually everybody uses the 510(k), doesn't necessarily mean that it is the best, and it certainly doesn't mean it is the only choice.

Jon Speer: Alright, good advice. So habit number 9, know all of your options.

Mike Drues: Yeah, again, this is related to what we just talked about Jon. So in order to really do your job as a regulatory professional, or as a medical device developer, you really need to know all of the different options that you have in order to get your medical device onto the market, here in the United States or elsewhere. Not just the vanilla flavored one, but all of the different options and the advantages and disadvantages of each. So one of the first things that I often do when I am brought into a new project is to put together what I call a regulatory strategy executive summary. It's not a full blown regulatory strategy, but it is a summary of the different options that the company has, the advantages and disadvantages to each, and to the extent that I can, an assessment of the regulatory burden and the regulatory risk of each one. In other words, if they take this particular path, this is what they are going to have to do in terms of testing, this is what their regulatory risk and the probability of successfully getting it through the FDA. On the other hand if we take a different path, then that is what they are going to have to do in terms of testing, that's what their regulatory risk is of successfully getting it through the FDA.

Mike Drues: And we discuss all of these options and we determine which option is best for that particular company. And one other thing that I would add to that Jon, and it is not on my list, I think I should add a number 16. Don't consider regulatory in isolation. Because we also have to bring in to this our reimbursement strategy, our product liability strategy. You mentioned earlier IP, our intellectual property strategy. So we have to meld all of these different things together, in order to choose the best path moving forward for our particular organization, for our particular technology.

Jon Speer: Alright. Moving right along. Let's dive into habit number 8. Don't be myopic about risk.

Mike Drues: Yeah, again Jon. This is another of my many favorite topics to talk about. In the interest of full disclosure, as you and some of your audience know, I happen to be a subject matter expert for the FDA in a few different areas. One of them being risk. I find, in a nutshell, all of the conventional approaches that we use to risk, all of the industry standards to be very limiting at best. Believe me, as an engineer, I am using very, very kind words. O think all of those are very limiting. So I developed several years ago, my own sort of approach, what I call my three bucket approach to risk. We have done a webinar on this, you and I have done a podcast on this. But it is something that the FDA is now more recognizing as a matter of fact, it has become my standard approach when I go to the FDA with a pre sub or even a submission. But especially in a pre-submission. Because I think it is a much more logical approach to risk than some of the others. Simply put there are aspects of risk that I think are very, very important to consider that are not even touched upon in some of the other approaches like the ISO approach, and I think that's why I find those other approaches to be so limiting.

Jon Speer: No, it's a really good point, and folks, if you haven't heard the webinar that we did on the ... Mike's approach to risk management, I would encourage you to go check that out. You can watch that on-demand from the Greenlight Guru website, but it's a really, I'll say, novel approach to it. But at the same time, it also, once you hear Mike ... I mean, all respect for this kind of ... how simplistic it is, it's a very logical methodology that you can easily apply to what you're doing at your company, so I do encourage you to explore that. And I want to remind folks today I'm talking to Mike Drues. Mike is with Vascular Sciences and Recovering the 15 Habits of Highly Effective Regulatory Professionals, so let's get right back into the list. And number 7: "New is not necessarily your friend."

Mike Drues: Well, so, first, Jon, I have to say thank you for the compliment on the risk side, and I do take that as a compliment because Albert Einstein, very, very smart guy, much smarter than me. He said, "If you can't experiment something simply, you don't understand it well enough," so I appreciate that you-

Jon Speer: Yeah, you're welcome.

Mike Drues: thought my explanation was simple. Anyway, so "New is not necessarily your friend." Yeah. This is habit number seven. It's a real challenge when I go to the FDA with a truly new, truly novel technology, and by the way, this is another one of those phrases that, I think, is very overly used. Somebody comes to me and says, "We're working on a new or novel device," and in about 30 seconds after describing it to me, I realize that they're not working on anything new or novel. So, several years ago, I developed a litmus test - if you think you're working on something new or not, ask yourself the following three questions: Is there regulation on it?; Is there guidance on?; Is there reimbursements for it?

Mike Drues: Once again, is there, if you're working on something new or not, ask yourself, "Is there regulation on it? Is there guidance on it? Is there reimbursement for it?" If the answer to any of those questions is "yes," then I hate to burst your bubble; you ain't working on anything new or novel because, at least in my book, "new and novel" partly means no regulation, no guidance, and no reimbursement. Now, when you take something like that to the FDA, as you can imagine, Jon, it's a real challenge because FDA is inherently ... I don't want to say "afraid," but inherently resistant or cautious about things that are truly new or novel for all of the obvious reasons.

Mike Drues: So, in order for FDA to ... in order for me make it a little easier for FDA to swallow that pill, so to speak, one of the first things I do, if I can, if I'm going to the FDA with something new or novel, is to deconstruct the technology. In other words, yes, on one hand this does appear to be new or novel, but if we pull it apart and we find one component of this technology has been used over here and another component of this technology is being used over there, and so on and so on, it makes it much easier for FDA to swallow that pill and, as a result, much easier for us to get that device onto the market.

Jon Speer: Yeah. And I think people fall in love with wanting something to be new, and I appreciate the desire for the thing that you're working on to be new. But take Mike's advice on this; it's very important. Remember that part of your challenge, as a medical device regulatory professional, is you need to tell the story of your product, and to hit Mike's plan about deconstructing and breaking down your device and your technology and to various chunks or pieces, if you will, to share what this piece is like and what this one is like and so on, it's gonna help better tell your story from a regulatory perspective. Heed Mike's warning here. I don't know if he stated it as a warning, but when you claim something is brand new, never been done before, it raises a lot of flags with regulatory agencies like the FDA because "new" means something completely different to a regulatory agency.

Jon Speer: It might require additional clinical studies, additional testing, additional things that you'll have to do to be able to corroborate that new is, in fact, okay. So, just keep that in mind. Number 6-

Mike Drues: And I would just add one-

Jon Speer: Yeah. Go ahead.

Mike Drues: -quick thing to that, Jon. Looking back to risk we talked about a few moments ago, the same logic applies to risk. As I said, as a subject matter expert for the FDA in the area of risk, I see companies frequently come into the agency with what they think is a new technology, and when it comes to the risk assessment, they say, "We don't know what the risks are because this is new. Nobody's done this before." Well, with all due respect, I think that's cop-out. That's an excuse because rarely ever can you not deconstruct the risks as well. In other words, there might be risks that aren't ... that you have in your technology that are similar to some drastically different technology. I'm not talking about similar devices. I'm not even talking about similar areas of medicine.

Mike Drues: I'm talking about you might be using one device in cardiology, and somebody else might be ... might have another device and OBGYN or something like that. But there might be aspects of risk that are similar between the two, so one of the things that I try to get people to do, Jon, is to look for similarities where those similarities seem to exist. Whether we're talking about technology, whether we're talking about risk, whether we're talking about regulation, it's all the same thing here.

Jon Speer: So, let me pose a question and, at the risk of it may ... I'm not trying to derail our going through the list of the habits of highly effective regulatory professionals, but you said something that triggered a thought. So, what if ... I mean, could I evaluate some sort of technology that's out of the ... outside the medical device space, as far as risk or technology and that sort of thing? Is there any credence or value in using non-medical device technologies when looking at something that I think is new or even looking at risk, is there any credence to doing so?

Mike Drues: It's a wonderful question, Jon, and my very short answer is yes. As a matter of fact, I would go so far as to say that if we did not do that, we would not be doing our jobs. We would ... that would be borderline professional incompetence, and I'll give you a perfect example. I have several devices that I'm working on right now that use ultraviolet or UV light to do something, maybe kill bugs or something like that. Well, there are a litany of technologies that are not regulated by the FDA that use the same technology to do the same thing, and so, even though those are not regulated by medical ... by FDA as regulated medical devices, I will still use that information as part of my regulatory due diligence, if you will. So, the short answer, Jon, is absolutely, yes, we can and we should use information from all sources, including non-regulated medical devices sources in order to do whatever it is that we're trying to do.

Jon Speer: All right. Number 6: use label expansions to your advantage.

Mike Drues: So, again, Jon, this is the topic that you and I have talked about many times. There are a range of options that companies can bring ... can use to bring their device on the market all the way through. On the one end of the spectrum, we have things like wellness devices that don't require anything from the FDA through the other end of the spectrum, which would be the PMA or the HDE, which would require a lot of regulation. Now, it's tempting for me, as an engineer, to want to bring a device to the market with all the bells and whistles that I probably can, but the problem is that, if I do that, it'd have a higher likelihood of being unsuccessful.

Mike Drues: Here's the metaphor that I often like to use, Jon. For those in the audience that are into baseball, it's the difference between swinging for a single versus swinging for a home run. Everything else being equal, I would love to swing for a home run, but the problem is, when you swing for a home run, in other words, getting all of the bells and whistles in your device the first time out of the box, you have a higher likelihood of striking out. And in this very risk-averse industry that we've evolved into, many companies don't want to take that risk, so I say, "Okay, fine. You don't want to swing for a home run, no problem. Swing for a single. Get the base hit." The batter moves to first. The next batter comes up. They get a base hit. The runner moves from first to second and so on. At the end of the day, you end up at the same place; you get ... the runner is all the way around the base. It's a matter of "Do you do it all at once, i.e. a home run, or do you do it as a series of singles or base hits?"

Mike Drues: Of course, there are advantages and disadvantages to both of those scenarios, but simply put, the label expansion idea ... and this is, in the regulatory world what I just described is doing a series of label expansion, very, very common in the drug world, not quite as common in the device world, although I do it myself all the time. It's a great way to get truly new, truly novel technologies, not just simply "me too" products onto the market through a regulatory structure that, let's just be honest, Jon, is not intended ... it is not designed to support that.

Jon Speer: Really good advice. All right. So, keeping with the theme of label, habit number 5: design your label like you design your device.

Mike Drues: Yeah. Once again, Jon, I find it interesting that a lot of companies obviously spend a lot of time and money designing their device, but when it comes to their labeling, they spend very, very little time, if any, designing their labels. In fact, in the 510(k) world, it's to your advantage to choose a label that's as close as possible to your competitors, but as we talked about before, you don't have to do that, Jon. So, long story short, as an engineer, to me, design is design. Whether I'm designing a physical widget, whether I'm designing a clinical trial, whether I'm designing a regulatory strategy, or, in this case, whether I'm designing a label, to me, design is design. And I want to use all of the tools, all of the tips and tricks that I can in order to do the best job of getting my message across, getting done what I need to get done.

Mike Drues: So, that's the idea of designing your label like you design your device.

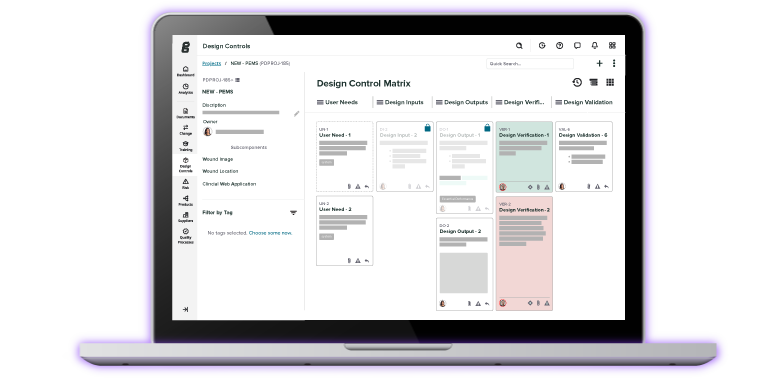

Jon Speer: Yeah. And, again, this is Jon Speer, and we're talking with Mike Drues of Vascular Sciences, and one of the things that ... just to echo what Mike's saying about this, don't treat your label as an afterthought. We talk a lot at Greenlight Guru about the importance of design controls, and, in fact, within our eQMS software platform that's designed exclusively for medical device professionals, we have a design control workflow. And it's important to include the label as part of that design control process, making sure you understand user needs and the design input requirements and things of that nature. I mean, there's a lot of information that gets crammed into a label. Some of it is, of course, driven by the current regulatory needs, things like UDI and things of that nature, but there's a lot of valuable information for that healthcare professional that needs to be on the label and the instructions for use and that sort of thing.

Jon Speer: So, spend the necessary time to make sure that you're not doing this as an afterthought or you're not trying to cram this in at the last moment. It is as important as any other part of that medical device, and if you'd like to learn more about how Greenlight Guru might be able to help you manage your design control process, I would highly encourage you to go to www.greenlight.guru to find out more information and certainly request a demo if that's something you're interested in. All right. So, how about number four, Mike: no submission should ever be rejected.

Mike Drues: So, speaking of baseball, Jon, we're in the bottom of the ninth, so we're coming to the end here. We've only got a few more habits to talk about. No submission should ever be rejected. Absolutely true. When you look at the statistics across our industry, Jon, quite frankly, they're abysmal. Something like three-quarters of 510(k)s are rejected by the FDA first time out of the box, and in the PMA world, it's even worse. About 89% of PMAs are rejected first time out of the box. Again, I think that's embarrassing, as an industry. We have people devolved, not evolved, but devolved to the point where we're really treating the FDA is our elementary school teacher.

Mike Drues: "Here's my homework assignment. Will you please mark it up and give it back to me?" And I'm sorry, Jon, maybe I'm getting a little old, but that is not the way this game is supposed to be played. So, I think the vast majority of these delays or rejections can be minimized if not totally eliminated by communicating with the agency in advance, and that's the theme of the last few tips here.

Jon Speer: Yeah.

Mike Drues: So, when ... I have said publicly many times that no 510(k) submission should ever be rejected because it's not substantially equivalent. That is such an amateur mistake. I mean, with all due respect to my regulatory friends, those regulatory folks probably shouldn't have the jobs they have if they're making those kinds of mistakes. That's just a huge problem. We can do better.

Jon Speer: Wow. And I think ... I know you've used the baseball analogy today, and, folks, a good hitter in baseball is going to get a base hit three out of 10 times. Hopefully that's not your track record as a regulatory professional. It should be quite different than 30 percent, so ... but it is ... there's a lot of rejections of 510(k)s. I think the latest statistic is something like three out of four 510(k)s are getting rejected or something like that, right? Right?

Mike Drues: That's correct, and when it comes specifically to substantial equivalence, it's even higher than that.

Jon Speer: That's crazy.

Mike Drues: So, 85% of 510(k)s are ... that are rejected are rejected specifically because of substantial equivalents. Again, Jon, this is another of the many topics you and I have talked about before: Substantial Equivalence, which is the crux of the 510(k). So many people think that it's such a simple thing, but what the heck does it really mean? It's not nearly as simple as a lot of people think.

Jon Speer: All right. So you hinted at this a moment ago, but let's dive into habit number three. Communicate early and often with FDA.

Mike Drues: Absolutely. As you and many in your audience, Jon, know there's no bigger fan of communication with the agency than I am. I will communicate much more frequently with the agency than any regulation would ever require me to do. But, Jon, there's a big caveat to that, as someone who works as a consultant for the FDA myself. I get the uncommon opportunity to sit on both sides of this proverbial fence so to speak. And it amazes me, Jon, absolutely amazes me how many companies come into the agency and essentially ask them - What do we do? How do we bring our device onto the market? What's our regulatory strategy? What kind of testing do we have to do? Do we have to do a clinical trial? And in my not so humble opinion, Jon, that's a terrible strategy for several reasons and I'll only just mention two of them here.

Mike Drues: First of all, it's not FDA's job to tell us what to do. It's our job to figure out what to do. What makes sense from a biology and an engineering perspective and then to take it the FDA and sell it to them. But the second reason why I think this is a terrible strategy is because you're opening up a Pandora's box, and you have no idea what you're gonna get in return. So if you go to the agency and you say, "Do we need to do a clinical trial on our new device?" What do you think they're gonna say, "Of course you gotta do a clinical trial, and you gotta use 500 million people." What else are they gonna say?

Mike Drues: So on one hand, there is no bigger component of communication with the agency than I am, but on the other hand there's my big caveat, and this has become one of my regulatory mantra and that is, "Tell, don't ask. Lead, don't follow." In other words, go out into the agency and say, here's the device. This is what it does. This is the way that it works. We're bringing it onto the market at the 510(k) and here's why we're a de novo or here's why we're a PMA and here's why. Here's the testing that we're doing. By the way I also justify what I'm not doing. So here's the testing that I'm not doing. I will also justify either why I'm not going to do a clinical trial or if I am going to do a clinical trial why the trial is designed the way it is. In other words, I wanna take away every possible opportunity that I have for the agency to disagree with me. So go in there and be quite confident and maybe even a little bold and, "Tell, don't ask. Lead, don't follow." Communication is a wonderful thing, but it's important to remember at the end of the day who's in charge.

Jon Speer: Yeah. All right. So getting down to the last couple. I feel like we should be approaching a drum roll here in a moment. Anyway, number two habit is don't treat FDA or, frankly, any regulatory agency as your enemy.

Mike Drues: Yeah. And regrettably, Jon, I see a lot of people approach the FDA with the attitude - what's the minimum that I have to do in order to get you to sign off on whatever it is that I want you to sign off on. And I'm just so troubled by that approach for so many reasons. As a matter of fact, many of my reviewer friends and some of the reviewers that I work with at FDA that I have been friends with for decades since we were in graduate school together. They have told me privately they would never admit this in public, I'm sure. But if you have people coming to you with that kind of an attitude every week even every day you might get a little skeptical. You might even get a little cynical. So I work really hard to try to break down that stereotype. So don't treat the enemy the FDA like it's your enemy. And along with that, Jon, don't treat the FDA as your beta tester. It amazes me, Jon, how many companies, the first people outside of their own organization to see their submission is the FDA. And in my opinion that's a huge mistake.

Mike Drues: One of the things that I do with a lot of the companies that I work with, I'm not trying to make this self-serving, I'm just trying to share some of my best practices is before the company goes down to White Oak to sell FDA whatever it is that they're trying to sell them. They'll ask me to come in to temporarily put my FDA reviewer head on to read through their submission and to sit through their presentation, and if I can be a bit brash here, you know, I'll bash the hell out of it, because the idea is if they're gonna make the mistake, better for them to make a mistake in front of me after all where do I count. I don't matter as opposed to down in White Oak where it really matters.

Mike Drues: For those like you, Jon, who are familiar with quality and the design controls, this idea should sound absolutely not new to you. This is right out of the design control since the concept of the independent reviewer. Only what I'm describing here is not in an engineering sense, but in a regulatory sense. So don't treat the FDA as your enemy, and don't treat them as your beta tester either.

Jon Speer: Really good advice. And it's folks from in ... I mean, FDA and other regulatory agencies they're -- I hate to use the term gatekeeper, but in many respects they are, and if you come to that gate and if you haven't earned, I'll use air quotes around the word earned that opportunity to pass through for whatever reason. It's gonna be difficult for you, so realize that FDA is a partner with you and other regulatory agencies they are a partner with you to get your product to the market, so treat them as you would any other good partner.

Jon Speer: And so without further ado, let's unveil the number one habit of highly effective regulatory professionals. And that is number one, don't be the regulatory police.

Mike Drues: Yeah. Jon, as I get older, I've been playing this game now for over 25 years. Let's be honest, in so many organizations and so many companies the regulatory and perhaps the quality folks as well, they're viewed as the police because they're constantly telling R&D and manufacturing and other areas what they cannot do. And I'm sorry, Jon, I do not take that approach. I pride myself on telling the company what they can do. In other words, when a company comes to me and says they have this really cool or what we would say here in Boston, wicked cool technology, I wanted to be able to come up with at least one usually multiple ways for them to get onto the market here in the US or whatever part of the world that they're looking to do business.

Mike Drues: So don't be like the regulatory police. Don't be telling people what they cannot do. Focus on what you can do. And similarly don't let regulation hold you back. Regrettably, I hear a lot of companies making excuses, "Well, you know, the FDA is being too burdensome. And it's too difficult for us to jump through these hoops." In some cases that might be true, but none-the-less, you have to work together to come to a compromise, because quite frankly, Jon, if everybody felt that way, we'd still be living in caves. Regulation and it pains me to say this, regulation has become a convenient excuse not to simply justify what we do but also what we don't do.

Mike Drues: One of the cool things about my job, Jon, is I get to walk into lots of different kinds of companies and I see what people are doing. They're doing some testing, for example, in R&D or manufacturing. And one of my favorite questions to ask them is, "Why are you doing this particular test?" And oftentimes they'll say to me, "Well, because FDA requires us to do it." I'll say, "Okay, fine. If FDA didn't require you to do it, would you do it?" Absolutely not. It provides no useful information. On the other hand, I walk into that same company and I'll see that they're not doing a particular test that I as the professional biomedical engineer think they should be doing, and I'll ask them, "Why are you not doing it?" They say, "Because nobody requires us to do it."

Mike Drues: So regrettably, Jon, and again, as a proud professional working in this industry for a long time, I take no joy in saying this, but regulation has become a convenient excuse for a lot of people, certainly not everybody, but for a lot of people to hide behind, and it's about time that we put an end to that.

Jon Speer: I love that. It's a good one to wrap up on. And folks, I think for regulatory professionals, this is my opinion based on current state of the industry and observations over many, many years. Regulatory professionals, you have an opportunity to really lead the organizations and kind of a new paradigm if you will, not to sound all cliché, but now more than ever there's a lot of confusion on regulations and how and what to do and when to do it and that sort of thing. And if you're coming to the other resources within your company carrying your internal regulatory badge if you will, it's not gonna be very well received. You have a responsibility maybe even to help explain the current regulatory structure that we operate in in the medical device industry. And so you have an awesome opportunity to really lead your organizations to be those best-of-breed companies who have leveraged and used regulatory in a really meaningful way that will help grow your businesses. I would encourage you to embrace this, not resist this. So, Mike, ...

Mike Drues: I could not agree more, Jon, and just to end my part because you need to wrap this up. If I can just share a short story to, I think, illustrate what you just described and I know I shared this with some of your audience in the past. But perhaps one of the most common questions that I get from companies, I get this question every week, sometimes even every day, Mike, you work with lots of different medical device companies, you also work for the FDA. If we came to the FDA with our new widget, what do you think FDA would want to see in terms of bench top, animal, clinical, usability testing, what have you. And I say to them, look, I understand why you're asking me that question. I understand why it's an important question to you. But let's approach this from a totally different perspective.

Mike Drues: Let's pretend for a moment that the FDA did not exist. Let's take them completely out of the equation. Sooner or later, a family member, a friend, perhaps even yourself is gonna be on the receiving end of your medical device. When that day occurs, what will it take for you as an individual, Jon, or for me, Mike, or for somebody else to put our personal stamp of endorsement, if you will, to say that that's okay to use in our selves, in our child, in my case, my almost three-year-old grandson, or even in ourself. Then and only then should we go to the agency, FDA or whatever regulatory authority and have an intelligent conversation as to what's necessary to bring this product onto the market.

Mike Drues: I'm a huge fan of doing what makes sense. What makes sense from a biology and an engineering perspective. Not simply following regulation like a recipe. That's another thing that far too many people do, and I think it's a problem.

Mike Drues: But anyway, thank you very much, Jon, for the opportunity ...

Jon Speer: Oh, you're welcome.

Mike Drues: I know that we covered a lot of information. And I would just mention for the people in the audience that are relatively new, many is not most of the topics that Jon and I talked about today. We have done in other podcasts or webinars in much more detail. So this was meant just simply to be sort of a high level, a shot gun, we went through these 15 topics as quickly as possibly we could. This was not an exhaustive list. With a little more effort, I think Jon and I could've come up with a list of 30 or more, but this is a good place to start.

Mike Drues: So thanks, Jon, for the opportunity to have this conversation.

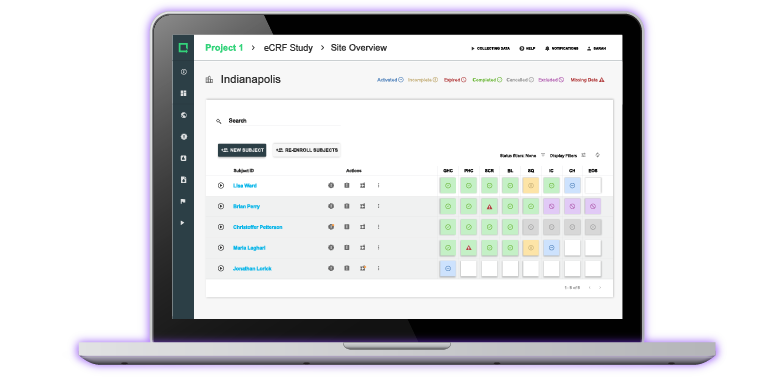

Jon Speer: Yeah. It's my pleasure. And folks, Mike is correct. You can almost use these 15 habits of highly effective regulatory professionals as a checklist of sorts so that you can evaluate where do you need to strengthen your regulatory knowledge or your regulatory skillset. And certainly, if you have additional questions or comments about this, feel free to reach out to Mike Drues with Vascular Sciences. You can find him all over the world wide web today. Certainly an active participant on a number of different medical device industry publications as well as LinkedIn. So feel free to reach out. And of course, folks, if you want to build a strong quality foundation for your medical device company to support your competitive regulatory strategy and documentation around design and risk and so on. I would very much encourage you to go to www.greenlight.guru to learn more about the Greenlight Guru QMS software platform.

Jon Speer: As always, this is your host, the founder and VP of quality and regulatory at Greenlight Guru Jon Speer, and you have been listening to the Global Medical Device Podcast.

ABOUT THE GLOBAL MEDICAL DEVICE PODCAST:

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Nick Tippmann is an experienced marketing professional lauded by colleagues, peers, and medical device professionals alike for his strategic contributions to Greenlight Guru from the time of the company’s inception. Previous to Greenlight Guru, he co-founded and led a media and event production company that was later...